In an age when society is again becoming highly polarized, it is important to remember that the lack of real communication causes a breakdown in civility, and an increase in ignorance.

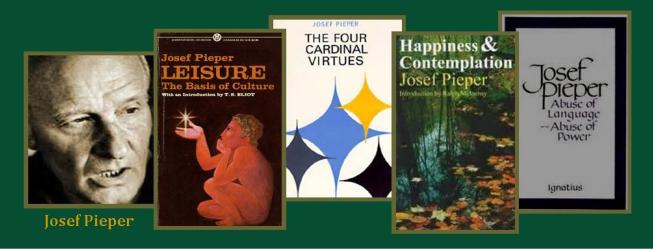

During his long lifetime, Josef Pieper (1904-1997) was known as a leading member of the neo-Thomist movement. When his most famous work, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1952), appeared in English, a reviewer at the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Pieper has subjects involved in everyone’s life; he has theses that are so counter to the prevailing trends as to be sensational; and he has a style that is memorably clear and direct.” The German philosopher can be easily ranked alongside Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson as one of the important Catholic thinkers of the postwar period. He made the theories of high academia approachable to the educated layman, and for many decades Pieper’s works were widely disseminated by both mainstream and religious institutions. Fortunately, many of them remain in print.

The first thing to note is Pieper’s unique style. Anyone sampling his writing will find it highly economical: there is no wasted thought or verbiage. Few of his books—most of which are long essays—are more than a hundred pages in length, and many are even shorter. But one should not be misled by his brevity. Within each of these studies is a mass of highly condensed thought and weighty considerations which span the millennia, from the pre-Socratic Greeks to the insights of 20th century intellects. Some of his works can be read in an hour or two. But they are studies that can last a lifetime.

The second consideration for the reader is the author’s highly integrated and harmonized outlook. There are many recurring themes—for example, his views on the meaning of philosophical dialogue, the idea of the incarnated soul, or the human capacity for leisure. For this reason, I will not approach his thought in terms of individual titles, which would result in a somewhat tedious and confusing list of books. Instead, I will treat each major theme systematically, and provide a bibliography for readers who want to pursue his major writings further.

Thinking and Leisure

For any person, no matter what his or her background, true awareness of self and surroundings begins with the “philosophical act.” According to Pieper, philosophy demands that we occasionally “step out of the world of work.” This is not, however, an excuse for snobbery or laziness. Pieper has no wish “to denigrate this world.” Without the things that go on in our daily life, we could not even begin to philosophize. There is (according to Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas) a very empirical and matter-of-fact quality to good judgment. Pieper wants us to take into account the immanent qualities of creation, as well as the transcendent aspects of the spirit.

The importance of thinking beyond everyday concerns is to avoid the potential tyranny of mundane pursuits. Any activity, even prayer, art, or love, can be perverted to serve the interests of the ego, or an overweening desire to master and manipulate things. Philosophy cannot be subservient, neither does it deal primarily with functional knowledge. It is this quality that makes it a “free” discipline, as in the traditional liberalia studia. For this reason, the German Thomist criticizes the political invasion of the arts and sciences. As soon as any academic discipline is forced to submit to ideological aims, it is perverted and ceases to educate; it becomes a tool for hubris and narrow interests.

To understand Pieper’s concept of philosophizing, we have to appreciate his notion of leisure. Drawing on the Western sages, both pagan and Christian, he is careful to make a clear distinction between leisure and idleness. The former refers to the contemplative side of man; the ability to passively receive knowledge and wisdom. This same sort of passivity is at work when we accept God’s grace. In a key phrase, Pieper says that “man seems to mistrust everything that is effortless; he can only enjoy, with a good conscience, what he has acquired with toil and trouble; he refuses to have anything as a gift.” He quotes Aquinas: “The essence of virtue consists in the good rather than the difficult.” This is in direct opposition to Kantian rationalists who denied that the contemplative life was superior to the active. They maintained that all virtue consists in action per se. Therein lies the modern egotistical need to constantly “assert” oneself as if to confirm one’s being.

Pieper explains that, for the Greeks, leisure originally meant education. It was time spent in intellectual activity—apart from servile work—which permitted men to contemplate higher things, not just technical learning, but inquiry into human society and individual responsibility. The arrival of Christianity expanded the meaning of contemplation further, by including the concept of prayer. The idea of the Sabbath, “and on the seventh day the Lord rested,” is an example of how the Church extended the freedom from servile labor to the entire community. What had hitherto been the prerogative of a few free men in a slave-based society, eventually became the privilege of all. Unfortunately, it is a privilege that has been severely undermined by a new paganism, which is far less respectful of reflection and contemplation than in many pre-Christian societies.

“Cut off from the worship of the divine,” says Pieper, “leisure becomes laziness, and work inhuman.” The answer is keeping inane distractions to a reasonable minimum, and substituting for them things like reading, creative activities, and, most of all, prayer. In this way, all aspects of our life can be transformed—not just in terms of public worship, but in our social and artistic pursuits. In the meantime, an earnest practice of religion will give us a real appreciation of the important things in life, including the idea of leisure.

It would be wrong, however, to mistake his arguments for antiquarian nostalgia, since to philosophize is not a form of idealism, whether of the left or the right. It means to “look at reality purely receptively—in such a way that things are the measure, and the soul is exclusively receptive.” To theorize is to think in a way untouched by pragmatic considerations, but also in a way that avoids “the smallest intention to alter things.” For this reason, Hegel and other secular theorists are essentially anti-philosophical, because they sought to impose the order of their minds on the order of the world.

At this point Pieper’s explanation becomes both rather subtle and extremely incisive. Man can philosophize because of his spiritual quality. Yet, curiously enough, an important part of this quality is his awareness of “the totality of existing things.” Man is thus not “pure spirit.” Pieper makes an interesting distinction between the “world” which man inhabits and his “environment.” The cosmos (ordered universe) is a much bigger place. By contrast, an animal is limited to its immediate environment because it can never step out of it. It merely survives. Human beings, on the other hand, can grasp relationships among existing things, through abstraction, that no irrational creature is able to perceive. Pieper laments that not all people take advantage of their supra-mundane qualities, yet philosophizing in this fundamental sense remains open to everyone.

The True Philosopher Is Not Wise

Pythagoras’ original definition of the philosopher (a lover of wisdom) was in deliberate contrast to that of the sophist (one who claimed to be wise). Students of history will recall that Socrates was continually sparring with the sophists in ancientAthens. These men would only dispense their knowledge for a fee, and emphasized the pragmatic use of logical and rhetorical technique, equating “wisdom” with mere cleverness. Obviously, a true philosopher will display great learning and discernment. He seeks wisdom with the proviso that it can never be fully possessed because it is infinite, and man is a finite being. Our wisdom, says Pieper, is always on loan.

Another humbling consideration is how few really new philosophical ideas there are. The ancient Greeks innovated such theories as atheism, materialism, hedonism, and even communism. Yet, Pieper (like Gilson) points out that the mainstream of Hellenic intellectual life was quite religious in its origins. The idea of philosophy being “emancipated” from theology and moral custom did not occur until the European Enlightenment many centuries later. While it is true that the early thinkers were often at odds with popular religion, this was mainly because they sought “to return to a more primitive” theology, shedding the absurd and often grotesque anthropomorphism of Homeric mythology. Plato was explicit on this point: “Knowledge came down to us like a flame of light, as a gift from the gods.” It is a tradition “handed down by the ancients.” Pythagoras and Plato believed that only divinity can possess complete knowledge or wisdom. But an awareness of the imperfection of human understanding, Pieper believes, is not an excuse for ignorance or despair.

Later, rationalists like Hegel attempted to redefine philosophy as a complete reordering of the universe according to our limited, subjective perceptions. The pessimistic Schopenhauer responded at the other extreme. In one sense, Schopenhauer was on the correct path when he said that human desires could never be fulfilled. His answer was to negate these desires completely. Pieper does not believe this necessary. To philosophize correctly is not to indulge in fashionable novelty or morose skepticism. To think is to wonder. It is this same sense of wonder that is at work in poetry and art.

“Since the very beginning,” says Pieper, “philosophy has always been characterized by hope. Philosophy never claimed to be a superior form of knowledge but, on the contrary, a form of humility, and restrained, and conscious of this restraint and humility in relation to knowledge.” For the Christian, “the greater truth” is to be found when we experience reality as a “mystery” rather than something to be grasped “by means of some transparent and marvelously clear system.” For this reason, “philosophical thought does not become simpler merely because one can cling to the norm of Christian revelation.” But, it is “truer and does fuller justice to reality” because it imposes what Aquinas understood as the via negativa (the “negative norm”), similar to the Socratic approach, whereby we learn from what we do not know, to know better what is still left for us to understand.

What Is Belief?

Confusion over the meaning of “belief” is at least as old as Socrates’ famous intellectual sparring with the young Euthyphro in the humorous dialogue of the same name. The first thing Pieper does in describing faith is what Socrates did when he wanted a philosophical definition. He looked at the meaning of a word and how it was used in everyday speech. It is clear that “belief” has different connotations. On the one hand, it can mean a mere guess or supposition, or maybe a qualified persuasion. But in religious terms, it can only refer to “unreserved, unconditional assent.”

The next point is that, according to the religious definition, belief deals with truths we do not fully understand. Where there is knowledge, Pieper notes, there is no need for belief. Thus, when we say we believe something that we do not fully comprehend, like the Heisenberg principle of quantum mechanics, we are doing so on the authority of someone else. Belief always points back to “one who knows.” In the case of the object of faith, which is God, only God himself fully comprehends the matter. This requires revelation. As Pieper explains, in Christianity “the content of the testimony (revelation) and the person of the witness (Jesus Christ) are identical.”

Finally, Pieper makes the point that belief does not imply an irrational “fideism.” Christianity is not a “blind faith,” such as one finds in fanatical or fraudulent cults. “No one who believes must believe; belief is, by its nature, a free act.” Nor is everything within the ambit of religion a matter of “faith,” since some things can be fully understood by our unaided minds. “The premises of belief are not part of what the believer believes.” In other words, a certain credibility or probability must be established about the testimony of revelation as a precursor to belief. That is the role of apologetics. But faith itself is never reasoned. It is ultimately a leap taken on an established trust.

Virtues and Vices

In his discussion of the cardinal virtues, Pieper explains that prudence—which is often viewed by idealists as a sort of shirking pragmatism—is really at the pinnacle of all the other virtuous habits. In this respect, the German philosopher is not only at odds with modernists, but also those “Christian” anti-intellectuals who imagine that faith supplants reason, or that the psychological make-up of the natural man can be safely ignored once the believer is in a state of grace. By its very definition, morality is more than a slavish obedience to a set of arbitrary commands. “If there were temperance in the sensual appetite and there were not prudence in the reason,” says Aquinas, “then temperance would not be a virtue.” That is because true prudentia implies a valid knowledge of reality, which, in turn, informs our judgments and actions.

The moralists tell us that a person’s strength is often the source of his greatest weakness, whether it is business acumen, artistic creativity, or physical excellence. Any of these things can be exercised too much or in the wrong way. Pieper explains that temperance deals with more than just chastity and lust. Following Aquinas, he acknowledges that man is a “sensual” being and that pleasure is a real and important dimension of his existence. It is the improper use of pleasure that is problematic. Pieper makes the point that such vices are never simply “private.” They have a public dimension.

To explore just one of the virtues thoroughly, consider the idea of bravery. The philosopher explains that fortitude “presupposes vulnerability … An angel cannot be brave, because he is not vulnerable.” Aquinas adds that “Fortitude without justice is a source of evil.” One need only think of the fanatical zeal of terrorists and revolutionaries. The essence of real bravery is not aggressiveness, self-confidence, or wrath, “but endurance and patience.” It is not that Pieper favors passivity over action. But “in the world as it is constituted, it is only in the supreme test, which leaves no other possibility of resistance than endurance, that the inmost and deepest strength of man reveals itself.”

The English Catholic poet, John Dryden, put it very bluntly: “Science distinguishes a man of honor from one of those athletic brutes whom, undeservedly, we call heroes. Cursed be the poet, who first honored with that name a mere Ajax, a man-killing idiot!” He was referring to one of the Greek champions of Homer’s Iliad, who was little better than a pirate. It is no coincidence that the medieval idea of chivalry held up for admiration the example of the Trojan Hector, the opponent of Ajax, who represented the domestic virtues of the settled and civilized culture.

Daring is not commensurate with rectitude. According to Pieper: “If the specific character of fortitude consists in suffering injuries in the battle for the realization of the good, then the brave man must first know what the good is, and he must be brave for the sake of the good.” Fortitude is not the first of the virtues “For neither difficulty nor effort causes virtue, but the good alone.” This hearkens back to his views on leisure.

Bravery, thus, “has nothing to do with a purely vital, blind, exuberant, daredevil spirit.” Referring to the paramount virtue of prudence, he warns that unreasoning fearlessness is based upon a “false appraisal and evaluation of reality.” In the case of the Viking berserker—chewing his shield and rushing half naked and screaming into battle—it can be foolishly blind to real danger. But there are other, more subtle dangers. Through a perversion of love, it can happen when a person values a “cause” more than his proper duty to himself or his neighbor. Finally, it can happen when men allow themselves to be forced into evil through fear.

Pieper says that while one should avoid the noncommittal optimism which seeks the good without sacrifice, “there is the equally pernicious easy enthusiasm which never wearies of proclaiming its ‘joyful readiness for martyrdom.’” St. Polycarp famously admonished Christians not to presume on their own strength. Martyrdom is something God calls us to; it is not something we should seek in an imprudent and hasty manner, especially since our courage might fail us at the last moment, thus setting an even worse example than if we had persevered quietly in whatever trials Providence might send us.

Reckless courage is wrong, not only in its methods, but also its ends. In a world that has increasingly lost its spiritual moorings, bored or alienated souls may react to the inanity of mainstream materialism by embracing the shallow romanticism of extreme behavior. First, fortitude must be guided by foresight which determines what choices we make, according to a wise assessment of the world around us. This is not an excuse for irresolution. A person well practiced in the ways of good judgment should be all the more capable of making snap decisions when the situation demands it, because fortitude has become inclination based on virtue (or good habits). Second, courage demands justice. In our actions, especially those which involve radical choices and the potential for great harm as well as great good, it is crucial that we assess what is due to others, as well as what is permitted to ourselves.

Language and Power

Pieper’s discussion of language reminds us of George Orwell’s famous essay, “Politics and the English Language,” in which the English writer warned that modern “political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.” Communication becomes prostituted to ideology, and genuine discussion is drowned out by verbal manipulation and denunciation.

As noted above, the sophists liked to “fabricate a fictitious reality” (in the words of Plato). For Pieper, words are meant to convey truth about the world around us. Language, as such, is not a specialized field, though the sophist treats it as such. It is not the skill or artistry of some people that Pieper is worried about, but the idea that language should become both recondite and easily manipulated to convey something less than reality.

The sophist puts style over content. Language is reduced to the art of persuasion and flattery. By flattery, Pieper means not merely that people are told things they like to hear; it implies an ulterior motive. Language becomes an “instrument of power” in which the speaker “no longer respects the other.” This is evident in the propaganda of totalitarian movements. They also indulge in flattery, insofar as they realize the importance of cajoling people into doing what they want, albeit backed by the implicit threat of violence. He states:

The dignity of the word…consists in this: through the word is accomplished what no other means can accomplish, namely, communication based on reality. Once again, it becomes evident that … the relationship based on mere power, and, thus, the most miserable decay of human interaction, stands in direct proportion to the most devastating breakdown in orientation to reality.

Of course, there is a deeper lesson here than just criticisms of political philosophies. Bad social behavior starts with corrupt communication inprivatelife, and public flattery would not work if people did not crave it in the first place. We should take Pieper’s analysis to heart, considering how we prevaricate, insult, and distort to get our way with others, or to cover up our own shortcomings.

True Dialogue

The ancient writer, Publilius Syrus, writes: “In too much altercation, truth is lost.” Along these same lines, the German philosopher notes that the pedagogical approach of the Middle Ages was based firmly on “the old Socratic-Platonic conception…that truth develops only in dialogue, in conversation.” Contrast this patient, collaborative outlook with the false idealism of wallowing in opinions and slogans that do not challenge one’s intellect, but merely confirm one’s biases.

It is true that youthful zeal can be an extenuating circumstance—“only the unflinching eagerness of youth, in its search for wisdom, could hope to prevail” against worldly cynicism. Nevertheless, if left uninstructed, zeal will eventually lead us into the trap of the endless monologue. This one-way form of communication is the opposite of classical discourse. Pieper notes that respectful dialogue was at the heart of such works as Aquinas’s Summa Contra Gentiles: “Truth must be brought to bear in and for itself, with its own inherent strength, and not by means of an adventitious force.”

Wisdom is the prudential use of experience necessary to perfecting one’s understanding. Part of this comes by communicating with, and learning from, others. Unfortunately, the idea of dialogue has been devalued and parodied in the form of self-indulgent group-therapy, talk show entertainment, or politically-motivated performances. In these instances, discussion is cut off from its proper end. Pieper reminds us that philosophical dialogue “is not the loving search for any kind of wisdom; it is concerned with wisdom as it is possessed by God.”

In an age when society is again becoming highly polarized, it is important to remember that the lack of real communication causes a breakdown in civility, and an increase in ignorance. Since the French Revolution, leftists have set a precedent for modern anti-intellectualism with their ideologies espousing pride and envy. Yet, an unthinking, reactionary attitude is no better. Not only does a “right-wing” monologue fail to convert the opposition, it also impairs dialogue amongst fellow conservatives. People lose the ability to discern the truth because they have forgotten that “philosophy cannot be put at the disposal of some end other than its own,” such as power politics or personal vanity.

_________

Select bibliography

Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power (Ignatius Press, 1992)

Belief and Faith (Pantheon Books, 1963)

Death and Immortality (St. Augustine Press, 1999)

The Four Cardinal Virtues (University of Notre Dame Press, 1966)

Guide to Aquinas (Ignatius, 1991)

Happiness and Contemplation (St. Augustine Press, 1999)

Leisure: The Basis of Culture (Ignatius Press, 2009)

That last paragraph speaks volumes about where we are in civil discourse. I will reflect and share this insight.

Although dialogue within the framework of western philosophy is important, the real need is to engage in a world wide dialogue with multiple philosophical traditions.