You could say that Christ’s glorious wounds are our wounds. He took our humanity to himself in the Incarnation … Christ’s humanity is completely ours.

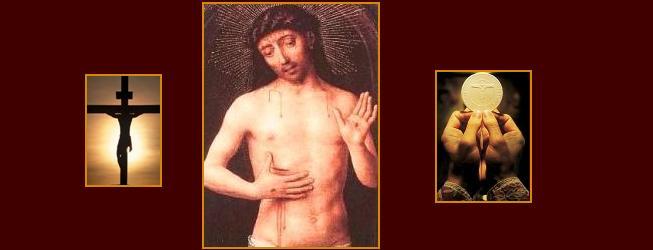

Central to the mystery of the Christian faith is Jesus Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection, known collectively in modern times as the “paschal mystery.” This unity can be most vividly seen in the glorious wounds of the risen Lord. Christ, now raised from the dead, is the same Christ who suffered and died upon the cross. Rather than effacing the marks of the crucifixion, the resurrection glorifies them. These wounds have special mention in some of the scripturally-recorded appearances of the risen Lord. In Luke 24:39 (NAB), we hear Jesus say, “Look at my hands and my feet, that it is I myself.” Jesus then showed the disciples his hands and his feet (cf. Luke 24:40). Even more prominently, the account in John 20:24-29 of the Apostle Thomas’s doubt and coming to faith, through the invitation to probe Jesus’s hands and side, allows us to probe the meaning of those glorious wounds. As we ponder them, we can find out something not only about the risen Jesus, but also about ourselves.

In his treatment of Christ’s resurrection, St. Thomas Aquinas asks in his Summa Theologiae III (q. 54. a. 4) whether Christ’s body should have risen with its scars. As always in the Summa, Aquinas begins with objections, the best objections that can be mustered against his own position. The first objection deals with how wounds signify corruption and defect. In more modern language, perhaps one could say that the wounds are gross. Isn’t the idea of someone coming to life after death while bearing the wounds of his death something from a horror film? Wouldn’t Jesus be more likely to say “Someone is going to pay for this” than “Peace be with you”? The second objection also is a matter of the gross factor: wounds destroy bodily integrity. The body just isn’t whole if there are gaping slashes. There’s something wrong, and it’s disgusting. The third objection runs likes this. It might be permissible to retain some sign of the crucifixion to confirm the faith of the disciples that he ,who was once put to death on a cross, now lives. But, why in the world would he continue to look like that? Since Christ’s body immediately after the resurrection is how that body is forever afterwards, it’s not fitting for him to rise with the scars from the crucifixion. The resurrection is forever, so let’s think about the long-term appearance of the body, particularly in what is to be the most glorified body of all. It wouldn’t be right to look that way.

Now, Aquinas knows that Christ did rise with wounds, and so the fact of Christ’s resurrected body having glorious wounds is the immediate answer on whether or not that should have occurred. It, in fact, did happen in God’s providence, and so we can then see how there was fittingness by God’s design. Aquinas’ arguments of fittingness (ex convenentia) are arguments of beauty, and, perhaps, there’s nothing quite like the beauty of his answers for the glory of the risen Lord.

In the body of the article, Aquinas gives his first answer as the first of five reasons coming from the Venerable Bede. Christ rose with his wounds for his own glory. It’s not that Christ couldn’t heal his own wounds, but that he wanted “to wear them as an everlasting trophy of his victory.” I was once explaining this to a class of young African men studying for the priesthood. I said that this idea of a trophy of victory is like someone who has survived a fight, but who bears a scar from a fight that he won. Rather than being some sort of embarrassment, the scar is something that he shows off to his friends. One of the African students quickly understood, and said that that was certainly true in his own case. He survived a terrible fight, and he is proud to show others what the fight did to his body. In the words of urban lingo, he gets “street cred.” Jesus, you could say, has this “street cred.” The Lord is able to show off—to have glory—for his victory over the fight against death itself.

As for the second reason from Bede, the glorious wounds confirm the disciples’ hearts for faith in the resurrection. Whereas the first reason was only for Christ’s own glory, this second reason is precisely for the faith of the disciples. This makes eminent sense, as this indeed seems to be the point in both the Lukan and Johannine descriptions of the post-Resurrection appearances. The risen Lord comes to show himself to his disciples, allowing them to see that he is indeed the same one who was crucified for their sake. He’s the same person, and now he asks for belief in his resurrection. Those glorious wounds also help us who do not literally see the risen Lord, but believe without seeing. They confirm the faith in our hearts as well.

The third reason, also from Bede, states that when Christ “pleads for us with the Father, he may always show the manner of death he endured for us.” The Letter to the Hebrews says of our high priest: “he is always able to save those who approach God through him, since he lives forever to make intercession for them” (Heb 7:25). Imagine Christ in the orans position showing his Father the wounds from his crucifixion. Christ died once for all, and he will forever show his Father the marks of his obedience unto death for our salvation.

Bede’s fourth reason switches from the third reason’s display to the Father, to the showing of the wounds to sinners: “that he may convince those redeemed in His blood, how mercifully they have been helped, as he exposes before them the traces of the same death.” This is the divine mercy, now another name for a Sunday marked by so many other names: Octave of the Resurrection, Second Sunday of Easter, Low Sunday, Quasimodo Sunday, New Sunday, Dominica in albis Sunday, Thomas Sunday…. As Divine Mercy Sunday, this eighth day of celebrating the Eighth Day, the new creation of the resurrection, is especially a day to consider how we have been treated mercifully. We didn’t deserve a new creation. We have been brought to the Day of unending light through the merit of Christ’s merciful wounds. The vision of Christ, provided by the canonized Polish nun, Faustina Kowalska, so beautifully captures how divine mercy comes into our own locked rooms, radiating from Christ’s pierced side.

The fifth reason continues from the perspective of sinners, but now on Judgment Day to those who rejected the divine mercy. Following upon Bede, Aquinas says that the risen Lord’s scars make manifest how the Lord will upbraid the condemned by their just condemnation. Aquinas also quotes words from a Pseudo-Augustine source that offer a heart-wrenching interpretation of what the wounded Christ on Judgment Day will say to the condemned: “Behold the man whom you crucified; see the wounds you inflicted; recognize the side you pierced; since it was opened by you and for you, yet you would not enter.” We know from Scripture that he will indeed expose those wounds to all. We read at the beginning of the Book of Revelation, “Behold, he is coming amid the clouds, and every eye will see him, even those who pierced him. All the peoples of the earth will lament him. Yes. Amen” (Rev 1:7). He is the lamb standing “that seemed to have been slain” (Rev 5:6). That Jesus will be seen as the victorious slain one will be for the utter pain of the condemned and the exuberant praise of the redeemed.

This reason from Judgment Day is powerfully rendered in the eighteenth-century Advent hymn, “Lo, He Comes with Clouds Descending,” originally written by John Cennick, and significantly altered by Charles Wesley and Martin Madan: “Every eye shall now behold him/ Robed in dreadful majesty/ Those who set at naught and sold him/ Pierced and nailed him to the tree/ Deeply wailing, deeply wailing, deeply wailing/ Shall the true Messiah see.” Another verse from the hymn recounts how the saints in heaven, among whom we hope to be numbered, will have a very different reaction to those wounds: “The dear tokens of his passion/ Still his dazzling body bears/ Cause of endless exultation/ To his ransomed worshippers/ With what rapture, with what rapture, with what rapture/ Gaze we on those glorious scars.” In the contrast of verses from this hymn, the reaction on Judgment Day to Christ’s glorious wounds signifies our everlasting disposition—wailing or rapture.

In answering the three initial objections, Aquinas focuses on the comeliness of those glorious scars that will remain forever. His argument of fittingness, particularly in this consideration of Christ’s body, has a remarkable attraction where we meditate on the glorious wounds as trophies of power. In fact, Aquinas posits that far from detracting, the greater beauty of Christ’s glorious wounds perfect his body. By answering these objections, Aquinas leads us to meditate with him on the perfect beauty of Christ’s body being raised with glorious wounds. There is an unexpected divine beauty coming from the ugliness of what human sin has done to the Lord. This beauty will last forever and ever, something for ceaseless contemplation in heaven.

Thomas Aquinas is but one of many saints on earth who have contemplated the meaning of Christ’s glorious wounds. Another which deserves special mention comes from the report given by Sulpicius Severus about the life of Martin of Tours. The fourth-century monastic bishop received an apparition. It seemed as if Christ, arrayed in regal attire, was appearing to him. Martin heard, “Acknowledge, Martin, who it is that you behold. I am Christ; and being just about to descend to earth, I wished first to manifest myself to thee.” But Martin kept silence. Then he heard again, “Martin, why do you hesitate to believe, when you see? I am Christ.” Finally, Martin knew what was really happening, and he replied, “The Lord Jesus did not predict that he would come clothed in purple, and with a glittering crown upon his head. I will not believe that Christ has come, unless he appears with that appearance and form in which he suffered, and openly displaying the marks of his wounds upon the cross.” At that, the devil was exposed and vanished like smoke, leaving a terrible stench. As the more famous story earlier from his life reports, Martin, while still a catechumen, had clothed the naked Christ. Martin came to know Christ through a bodily way marked by humility. What we find in this lesser known later story is Martin’s firm conviction that Christ always has wounds. If he doesn’t, that’s not Christ. It’s the devil.

Now, if the cross of Christ has this effect upon his glorified body, what does this say about our humanity? Most certainly, we affirm that Christ’s humanity is our humanity. The reason for the Word to be made flesh, suffer, die, and rise was to have our humanity experience the transformation into the glory that he had with the Father before the world began. You could say that Christ’s glorious wounds are our wounds. He took our humanity to himself in the Incarnation. It is our humanity that suffered, died, rose, and ascended to the right hand of the Father. Christ’s humanity is completely ours.

Yet, we could ask about its significance beyond the identification of Christ’s humanity as belonging, in a very real sense, to us. Could others rise with glorious wounds in the pattern of Christ’s paschal mystery? Wouldn’t this show how Christ’s resurrection is the principle of the general resurrection? Isn’t this an actualization of what St. Paul says, “He will change our lowly body to conform with his glorified body” (Phil 4:21)?

St. Thomas suggests as much in his very consideration of Christ’s glorious wounds. Within his first answer, after citing the Venerable Bede, he quotes Augustine’s City of God: “Perhaps, in that kingdom we shall see on the bodies of the martyrs the traces of the wounds which they bore for Christ’s name: because it will not be a deformity, but a dignity in them; and a certain kind of beauty will shine in them, in the body, though not of the body.” We may be used to something of this idea through the symbolism of religious art. The apostle Bartholomew holds out his flayed skin. The virgin Lucy offers her eyes on a platter. The Dominican priest Peter Martyr has blood dripping from his pierced head. But perhaps, these depictions are more than simply identifications to help the viewers understand who is being portrayed. Perhaps, these testify to a reality where the martyrs will, like our Lord, possess a great bodily dignity, a distinctive beauty in the resurrection, because of their particular suffering unto death. That was Augustine’s speculation, a meditation continued by Aquinas, about the martyrs.

As for the resurrection of all the saints, medieval scholastics loved to debate the dotes, the endowments of the glorified body based upon the characteristics of Christ’s own body: subtilitas, agilitas, impassibilitas, and claritas. Unfortunately, the quality of the general resurrection of the saints is irrelevant to many theologians today. As a result, heaven has become even more difficult to imagine. However, what if, taking a cue from the scholastics, yet asking a new question, all the saints in heaven were to show forth in bodily form their personal configurations to Christ’s cross? Jesus says, “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me” (Mark 8:34). Since there is no resurrection without the cross, I think it would be fitting that all would somehow display their unique cross in experiencing the fullness of Christ’s paschal mystery in the glory of heaven. What would that look like?

It is easiest to consider the non-martyred, canonized saints, as those are guaranteed by the Church to be in heaven. Here’s one example, impressed upon me by one of my Dominican confreres. In his encyclical on hope, Benedict XVI speaks movingly of Josephine Bakhita. Near the beginning of Spe Salvi, Benedict says that Josephine bore 144 scars through her life due to the cruelty of one of several masters she endured in her youth. When she was sold again and brought to Italy, she came to know another master, a paron in the Venetian dialect. Benedict says, “{S}he heard that there is a ‘paron’ above all masters, the Lord of all lords, and that this Lord is good, goodness in person. She came to know that this Lord even knew her, that he had created her—that he actually loved her. She too was loved, and by none other than the supreme ‘Paron,’ before whom all other masters are themselves no more than lowly servants. She was known and loved and she was awaited. What is more, this master had himself accepted the destiny of being flogged, and now he was waiting for her ‘at the Father’s right hand’” (Spe Salvi 3). Josephine Bakhita was later baptized, and became a Canossian Sister, who modeled forgiveness and love of enemies. When people would express their pity for her, she would say that it is her enemies who should be pitied, as they didn’t know Jesus. Imagine Josephine Bakhita in the happiness of heaven, the fulfillment of her hope, now with glorified wounds. She shows these glorious wounds to Jesus, as a triumph of victory with him in forgiving sinners. She shows these glorious wounds to the other saints, as a particular badge of co-membership with them in the body of Christ, who suffered, died, and rose for our salvation.

On the principle of conformity to Christ’s paschal mystery, it can be posited that the glorified souls of all the saints will be manifest through their glorified bodies. The indescribable joy of the soul from the beatific vision spills over into the body, radiant in joy. This contrasts with the pain of this present life on earth. So much of suffering in union with Christ’s suffering is hidden, as the spiritual reality of the soul is itself so hidden, so obscured, by the heaviness that weighs us down as we go through the valley of tears. Perhaps, the internal, secret victory over sin, won by God’s grace during this time of trial and temptation, will be made manifest in a way that will allow the marks of our particular cross to shine out in radiance. Already, during this life on earth, God’s grace pours over the soul’s wounds in its conformity to Christ’s cross. In heaven, God’s glory will be making the body a visible sign of the interior victory achieved on earth. Imagine how saints who have suffered wrongs patiently will be shining with marks of patience that have been made radiant in heaven’s light. Imagine how saints who have won the victory over lust will be beautiful in the purity that allows them to see God with eyes of extraordinary love. Imagine how saints who have humbled themselves will be wonderfully great in the kingdom of heaven. Their own conformity to Christ’s paschal mystery will be seen, seen in bodily form.

I was once talking with a recovering alcoholic about this idea that all the saints will have their crosses made known in luminous glory. He replied with some dejection, “Will I have a beer can tied around my neck?” I don’t know that. But I do know that the saints in heaven have no shame. The sufferings that they underwent on earth were precisely the way that they are conformed, by God’s grace, to Christ’s paschal mystery. These sufferings, in their various forms which are often so secret, so ingrained in our very being during this life, are participations in Christ’s own cross. St. Paul says, “May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6:14). This is our boast during this life, and it will be the boast of all in heaven. It will not be disgusting, but all beautiful.

Therefore, in meditating upon our own participation in the fullness of Christ’s paschal mystery, we can catch a glimpse at how our struggles in grace are not in vain. Our conformity to Christ’s cross now will allow us to share the victory of the risen Lord, marked forever by the scars of the redemption he won for us. By thinking this way, heaven becomes even more real for us who know, all too painfully, the reality of the battle we are fighting upon this earth.

As we are invited with the apostle, Thomas, to probe in faith Christ’s wounds, we can come to believe that the glorious wounds are not only Christ’s, but ours as well.

[…] to the Source: Homiletic & Pastoral Review #ssba img { padding: 5px; border: 0; box-shadow: 0; display: inline; vertical-align: middle; } […]