Introduction

Consider how central the Trinity is to our faith. We invoke the Trinity at the start and end of every Mass when we make the Sign of the Cross; those of us who pray the Rosary or the Divine Office will invoke the Trinity countless times at every Glory Be. This tells us perhaps the most important thing about the Trinity: the Trinity is first and foremost a matter of how we pray, not what we believe.

That being said, understanding what we believe is crucial to our spiritual life, not only so that we may love God with our mind as well as our heart, but that we may truly love our neighbor: we don’t take our neighbor seriously if we don’t take seriously the questions and objections they present to us, including their questions and objections to the doctrines of the Faith. And there is perhaps no doctrine more objectionable or questionable in the Christian faith than the doctrine of the Trinity. At the heart of the doctrine of the Trinity is the claim that God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: three persons in one God. The purpose of this short essay is to consider the most popular sort of philosophical objection to the doctrine of the Trinity, to criticize some responses commonly encountered in Christian circles, and to put forward, in brief, the outlines of a better response which takes its inspiration from St. Thomas Aquinas.

What Is the Main Philosophical Objection to the Doctrine of the Trinity?

At the heart of philosophical objections to the Trinity is the claim that the doctrine is illogical and somehow involves deep contradictions. It is worth noting at the outset that such accusations of incoherence or contradiction are often based on plain ignorance and misunderstanding. Some years back, as an undergraduate philosophy student, I remember an atheist friend publicly remarking in class one day that Catholicism is illogical because the Trinity requires believing in three Gods and one God at the same time. My friend’s accusation was honest but ignorant: the doctrine of the Trinity does not say there are three Gods and one God at the same time, nor does it say there is one person and three persons. Rather, it says that there are three persons in one God.

However, it would be unfair to characterize all such accusations as based on ignorance or misunderstanding. Many intelligent nonbelievers object to the doctrine of the Trinity, even after basic misunderstandings have been brushed aside. We can frame the more serious kind of objection in terms of a logical law sometimes called Leibniz’s Law: if two things are identical, then they must share all the same properties or characteristics.1 To illustrate this law, imagine I want to find out information about Pope Francis and therefore (naturally) google him online. There, I find lots of websites about a man named Jorge Bergoglio. What’s the relationship between this Bergoglio and Pope Francis, I wonder to myself? So, I (naturally) look up “Bergoglio” on Wikipedia, at which point I find the search redirects me to the Wikipedia page of Pope Francis. This makes me realize: the relationship between Bergoglio and Francis is one of identity: Jorge Bergoglio is simply identical to Pope Francis. Suppose I now find out Bergoglio was Archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1999. That tells me something about Bergoglio. But what does it tell me about Francis? This question should strike you as somewhat artificial: we almost unconsciously would infer that, since Bergoglio is identical to Francis, Francis must also have been Archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1999. What is at play in this unconscious inference is Leibniz’s Law: the basic principle that since Francis and Bergoglio are identical beings, they must share all the same properties. In short, Leibniz’s Law is one of the most basic principles of logic, one that is so basic we invoke it constantly without thinking about it.

How does Leibniz’s Law figure in serious objections to the Trinity? At the heart of these objections we find the claim that the doctrine of the Trinity appears to contradict Leibniz’s Law because the doctrine of the Trinity seems to involve the following affirmation: the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are all identical to God, but the Father, Son, and Spirit are not identical to each other. This seems to be in blatant contravention of Leibniz’s Law: if both the Son and Spirit are both identical to God, surely it logically follows (from Leibniz’s Law) that the Son and Spirit are both identical to each other, a conclusion which is denied by the doctrine of the Trinity. O,r put differently, if both the Son and God are both identical, surely it logically follows (from Leibniz’s Law) that the Son and God share all the same properties, a conclusion which is denied by the doctrine of the Trinity (the Father lacks the property of being the Son or the Holy Spirit, whereas God has the property of being the Son and being the Holy Spirit). This objection is a serious one and it can’t be easily dismissed. It is not based on an obvious misunderstanding of the Trinity, and Leibniz’s Law is a fundamental logical law which seems futile to deny. (Denying Leibniz’s Law seems to be on par with denying the principle of non-contradiction: even those rare philosophers who claim to deny it are met with skeptical gazes, precisely because it seems practically impossible to avoid using something very much like the principle of non-contradiction in everyday reasoning. The same could be said for Leibniz’s Law).2

Is “Mystery Alone” Sufficient?

The logical objection to the Trinity is a philosophical objection, and there are many Christians, often non-Catholic Christians but increasingly many Catholics, who will reject philosophical objections to matters of faith out of hand. They will say something like this: “Look, there are lots of philosophical objections you can raise to this aspect of our faith but, ultimately, the faith is not a philosophy, the faith is a mystery which cannot be reduced to a convenient logical human system. You need to stop arguing and ask for the grace to be open to the mystery.” Let’s call this kind of reply the “mystery alone” reply.

Now, as with all wrong views, there is a grain of truth in the “mystery alone” reply. After all, it is true that there are lots of mysteries in our faith we will not comprehend. And it’s even true that, in some situations, an appreciation of the mystery can be the best answer to the objection. For example, when Job asks why God has inflicted so much evil and suffering on him and his family, God in effect tells Job to stop questioning and to appreciate the transcendence and mystery of God’s ways. Ultimately, though, the reason why the “mystery alone” reply is wrong in our present context is that our faith should never require us to believe contradictions. But the logical objection to the Trinity we have been considering is an objection which supposes that there is a contradiction between faith and reason, specifically, a contradiction between the Trinity and the self-evident truth of Leibniz’s Law. To respond simply by appealing to mystery, is in effect to concede that our faith involves mysterious contradictions. The problem with mysterious contradictions is that they are still contradictions. Suffice it to say that any perspective which embraces contradictions is not a truly Catholic or indeed Christian perspective. After all, the God of Scripture and Christian tradition is not a God who requires us to abandon reason; rather, he is the Logos, the ultimate rationality undergirding all we know and understand. True Christianity does not require faith and reason to pull in opposite directions. Rather, to borrow an image from St. John Paul II, they are (or ought to be) like two wings jointly assisting us in our upward flight toward the Truth of God. For this to happen we need to embrace, not the “mystery alone” response, but rather the “mystery and philosophy” response.

What does the “mystery and philosophy” response look like? It is helpful to begin by noting Alvin Plantinga’s onetime remark that philosophy is, at bottom, nothing more than “thinking hard.” Instead of dismissing objections such as the logical objection out of hand by appeal to the need for mystery, the “mystery and philosophy” response requires thinking hard about the objection and providing a serious answer which, as far as possible, does justice to what the objection gets right. An increasing number of theologians and philosophers hold (and I agree) that what the logical objection gets right is Leibniz’s Law: our understanding of the doctrine of the Trinity should not be one that requires us to revise or abandon it. However, any response to the logical objection to the Trinity which seeks to remain faithful to Leibniz’s Law will of course need to remain faithful to the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. And it is in this regard that the responses of many modern theologians to the logical objection can, and have been, called into question.

Is the Trinity Best Understood as a Divine Community?

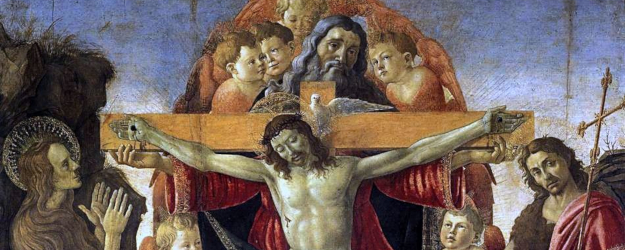

Consider, for instance, one increasingly popular modern strategy of responding to the logical objection,3 which comes down to the following basic claim: where the doctrine of the Trinity calls us to affirm that the Father “is” God or the Son “is” God, this should not be interpreted as an identity claim: that is to say, it should not be interpreted as the requirement that we affirm that the Father and the Son are identical to an individual, God (in the way that, e.g., Bergoglio is identical to an individual, Francis). Rather, when we say the Son “is” God, we are saying something more akin to the statement that the Son “is” divine.4, 575-96; William Lane Craig, “Toward a Tenable Social Trinitarianism,” in Philosophical and Theological Essays on the Trinity, ed. Thomas McCall and Michael Rea, 89-99 [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009]). “A soul which is endowed with three complete sets of rational cognitive faculties, each sufficient for personhood” (594).] Saying that the Son is divine is not an identity statement like “Bergoglio is Francis”; rather, it is more like the attributive statement, “Bergoglio is Catholic.” That is, it attributes a property or feature to the subject; in this case, it attributes to a person of the Trinity the property of being divine. An image that might help us visualize the consequences of this view of the Trinity is Rublev’s famous icon of the Trinity. What one sees in that icon is a divine community. The image arguably captures one God in three persons, with the crucial additional qualification that what it is to be God is not to be identical to a single being (God) but rather to share in the one essential feature or property of divinity. On this view, it is a mistake to look for a single individual “God” in the Trinity just as it would be a mistake to look for a single individual in Rublev’s icon: “God” is just the one attribute of divinity shared by all the persons of the Trinity.

It is easy to see why this interpretation (call it the “divine community” interpretation) is popular: it provides a clear answer to the logical objection, because (recall) the objection arises only given the assumption that each person of the Trinity is identical to God, for it is the identity between the persons and God which leads to contradictions (due to the differences which also obtain between the persons). It also captures the reality of relationship and community within the Trinity, a reality to which we find a strong witness in the New Testament (think of Christ’s prayer to the Father during the “agony in the garden” in Mt 26:39ff).

However, there is a serious difficulty for the divine community view: it seems to eliminate the most important part of the doctrine of the Trinity, the claim that there is one God. On this divine community view, there are three persons, and although they all share in one divinity, divinity is just an attribute had by each person. This view seems to verge on polytheism, the view that there are many gods, as opposed to just one God.5

If you find this consequence troubling, and find yourself unsatisfied by attempts to avoid the conclusion that the divine community view does in fact lead to polytheism, you may find yourself asking: are there any alternatives? In what remains, I will explore an alternative response to the logical problem, one that is inspired principally by Aquinas but has been endorsed by many Church Fathers of both East and West.6 Unlike the foregoing strategy underlying the divine community view, this alternative response does not reject the identity between each divine person and God. Rather, it follows Aquinas in distinguishing between different kinds of identity, some of which are “strict” (i.e. obeying Leibniz’s Law), others which are weaker (and which do not obey Leibniz’s Law).

To see the difference between strict and weaker forms of identity, consider the following example. The identity between Jorge Bergoglio and Pope Francis involves strict identity, “identity-without-distinction,” since there is no room in that identity to make any additional meaningful distinctions between Francis and Bergoglio. They are absolutely and the same individual, just called by different names, with absolutely no difference between them, full stop.

But according to Aquinas there are other, weaker sorts of identity, like the relationship between matter and form.7; Jeffrey E. Brower and Michael Rea, “Material Constitution and the Trinity,” in Philosophical and Theological Essays on the Trinity, 263-82. Terminological note: Whereas Brower speaks of “sameness without identity,” I, on the other hand, speak of two forms of identity (weak and strong) in Aquinas, simply for the sake of considerations due to Aquinas’s own terminology in his discussion of the Trinity (see, inter alia, the claim in Summa Theologiae I.39.5 ad 4 that “the divine essence is predicated of the father by way of identity”). There are other differences between Brower’s approach and my own, but for the purposes of this paper they can be treated as primarily terminological differences.] To illustrate this, consider a statue made of bronze, Botticelli’s David. When you look at it you might think there is just one thing there, the bronze statue. However, Aquinas says there are two things there: the bronze, which is the matter, and the structure of the bronze, which is the statue. If I were to ask you, “is the bronze identical to the statue?” You might wonder why I would ask such a strange question, but you would probably agree that yes, the bronze and the statue are identical. However, Aquinas also argues that there are distinctions you can make between the bronze and the statue. For example, if someone were to melt the statue and leave it in a lump of hardened bronze on the floor, they would have destroyed the statue but not the bronze. So, actually, the bronze can outlast the statue, kind of like how the soul can outlast the body. So just as the soul is distinct from the body precisely because it can outlast it, the bronze is actually distinct from the statue precisely because it has a property that the statue doesn’t have, namely, being able to survive through the destruction of the statue. The purpose of this strange example is simply to illustrate Aquinas’s point that there is more than one kind of identity: strict identity like the identity of Bergoglio and Francis, and weaker identities such as the identity of bronze and the statue. The weaker identities are still a kind of identity, but they allow for differences between the identical things, just like there are differences between the statue of David and the bronze making up the statue.

Aquinas makes this point about the Trinity: he says that when we say the Father is identical to God, it is really identity: indeed (and in contrast to the divine community view), the fact that an identity relation obtains between God and the Father allows us to say that the Father and God are not only inseparable but literally one and the same: our saying “Father” simply involves us considering God from a different point of view than when we say “God,” with different things coming into consideration. And yet there is no risk of modalism (the heresy that the Father and Son are simply different, non-permanent manifestations of the one God), since the identity between the Father and God is a weaker identity than strict identity (such as that obtaining between Bergoglio and Francis). This kind of identity allows for real, objective, eternal distinctions within the Trinity: it allows the Father to have features that God doesn’t have, such as the fact that the Father is really distinct from the Son and the Spirit, even though God is not distinct from the Son and the Spirit. Aquinas’s use of multiple forms of identity provides us with resources for a good answer to the logical objection, one that is just as strong as that offered by the divine community view, and, importantly, one that avoids any risk of entailing polytheism.

These distinctions between weak and strong identity are somewhat subtle distinctions, which is perhaps one reason why models of the Trinity suggestive of a divine community are more attractive to many defenders of the Trinity. However, there is a guiding image from Aquinas which I think can help us to understand his view of the Trinity, and which I would like to end my discussion with. This image centers around Aquinas’s claim that God is “pure act.” God’s activity, on this view, is so perfect and infinite and all-powerful that there is no distinction between God and his action, he just is his activity. What is that act? It is perhaps impossible for us to describe, but Aquinas maintains we can at least recognize it contains (in a much higher way than is found in human actions) thinking and loving. This thinking and loving is not primarily directed at human beings, or any other part of creation: after all, even before the first day of creation, God’s thinking and loving would have remained undiminished. Prior to creation, when only God existed, God’s thinking and loving would have been simply directed toward himself. While in human beings, self-love is often associated with the tendency to selfishness, self-love and self-knowledge in God is so infinitely perfect that it even generates relationships within God, relationships which form the constitutive basis of the Trinitarian persons.8 These relationships do not create divisions or separations within the pure act of God: rather, as mentioned above, they form the basis of “identities with distinction” in the Trinity.

Of course, this view of the Trinity is very different from the divine community of Rublev’s icon. It is very hard to see distinct persons in a God who is an utterly simple, undivided, pure, infinite act of endless knowing and loving. It is without doubt a radical theological picture of God, and there are all sorts of challenges and questions that one might raise against this view. For example, one might wonder whether this understanding of God as single pure act can really make room for three divine persons in God. These questions are at the heart of Catholic theology, and I find that Aquinas and many contemporary Thomistic theologians offer insights into answering these questions. But there are those who disagree with me, and find Aquinas’s picture of the Trinity too radical and divergent to be of any help at all. In reply, I can only concede that Aquinas’s account of the Trinity (and the patristic and classical theistic tradition he follows) is indeed a radically different account of God, perhaps overly so. But Trinitarian theology is also the loftiest and hardest part of all theology, harder perhaps than all the problems in science and philosophy put together. We can’t expect easy or ordinary answers.

I have argued in this paper that we should not settle for mysterious contradictions in our faith; rather, we ought to approach the Trinity as a rational mystery, one that requires us to bring reason and faith together in making deeper contact with the Trinity. If the Trinity is indeed at the pinnacle of Christian revelation, and if we are indeed called to love the triune God with all our mind as well as all our heart, perhaps it is time for us to acknowledge that our Christian faith demands of us not only a radical spiritual life, but also some radical thinking about the Trinity. Indeed, it may require us to embrace some radical theological ideas.9

- Leibniz’s Law is a label sometimes given to other philosophical theses (e.g. the controversial thesis of the identity of indiscernibles). By contrast, for the purposes of this paper, I use Leibniz’s Law to refer to the thesis sometimes also known as the indiscernibility of identicals. ↩

- For an example of an attempt to reject Leibniz’s Law on Trinitarian (and indeed allegedly Thomistic) grounds, see Peter Geach, “Aquinas,” in G.E.M. Anscombe and P.T. Geach, Three Philosophers (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1961) and P.T. Geach, “Ontological Relativity and Relative Identity,” in Logic and Ontology, ed. Milton Karl Munitz, 287–302 (New York: New York University Press, 1973). ↩

- Cf. Richard Swinburne, The Christian God (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 170-91. ↩

- This strategy is taken by William Lane Craig (cf. “The Trinity,” in J.P. Moreland and William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview [Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2003 ↩

- This statement requires qualification, for while polytheism is obviously a heretical view, that is not to say that anyone who thinks of the Trinity as a divine community is thereby a polytheist or a heretic. My point is simply that, in the absence of some adequate explanation as to why the three persons are one God, the divine community view runs the risk of entailing heresy. Many theologians (such as Swinburne and Craig) would hold that there are such explanations at hand. I disagree, but a pursuit of this issue lies outside the scope of the present paper. ↩

- Cf. e.g. Augustine and Gregory of Nyssa. ↩

- The discussion that follows is indebted to recent work on Aquinas’s understanding of sameness and identity by Jeffrey Brower (cf. Jeffrey E. Brower, Aquinas’s Ontology of the Material World: Change, Hylomorphism, and Material Objects [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014 ↩

- The Father is the active relation of conceptualizing and loving, while the Son is the passive relation of being conceptualized (by the Father) and the Holy Spirit is the relation of being loved (by the Father). ↩

- An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2018 “Big Q” conference at St. Dominic’s Priory, Camberwell, and I am grateful to attendees for their questions and feedback, and to Fr Thomas Azzi, OP; Fr Michael Tavuzzi, OP; and Fr Joseph Vnuk, OP, for their assistance as I prepared this paper. ↩

Dear Reginald Mary Chua OP, The Peace of Christ. Thank you for a stimulating article. In the first place, however, if I have understood correctly, Pope Francis and Bergoglio are not identical according to Leibnitz’s law of identity, as Bergoglio did not become Francis until he became pope. Therefore, while they are one and the same person, Bergoglio is the more fundamental identity although Pope Francis is the most recent expression of it. As regards the soul outliving the body, while an analogy, is counterproductive because it encourages a superficial view of the body-soul relationship. One of the greatest needs of our time is a more integrated understanding of the unity-in-diversity of the human person; and, indeed, Pope St. John Paul II is a marvelous thinker in this respect: the relationship is one of ‘incarnation’ (Familiaris Consortio, 11; and cf. Conception: An Icon of the Beginning).

‘Person’ in philosophy has the meaning of ‘relation’; and, therefore, there is the mystery of the identity of a person in terms of how that person is ‘related’ to another (you mention this). This is immensely helpful to understanding human nature as, instead of a kind of individual which exists almost in isolation from others, like the philosophical concept of ‘substance’, we have the understanding of the human person as a human being-in-relation (cf. The Human Person: A Bioethical Word).

Finally, this leads into grasping the mystery of the creation of Adam and Eve as a mystery of ‘relation’: Adam is “generated” from the ground and Eve “proceeds” from Adam and, as it were, is one from the one breath of life that God breathed but nevertheless she is a different personal expression of it; and, therefore, the whole imagery of the creation of Adam and Eve is a kind of implicit account of the mystery of the Blessed Trinity that is suggested in the words for God in the opening chapter of Genesis (Elohim; Ruach Elohim) – indeed just as chapter 2 gives us a third “person”, the Lord God (Adonai Elohim), so does the creation of Adam and Eve complement the opening chapter of Genesis by giving an account of how Adam and Eve not only came to be but are, as it were, in the ‘image and likeness of God’ (cf. Scripture: A Unique Word, Cambridge Scholars Publishing etc. and other books for a more complete account of this understanding of the Blessed Trinity, Scripture, the human person etc.). God bless, Francis.