Speak only the words men need to hear, the things that really help them . . .

(Ephesians 4:29)

Introduction

The effects of language—for good or ill—first occurred to me when I was five, during the summer before kindergarten. As my brothers and sisters were playing with the neighborhood children, an older boy, Liam, asked if I wanted to “do something nice” for my parents. After I replied “Sure!” (fool that I was!) he directed me to go up to them and say just one word: “____.” It was the first time hearing the word and, as I recall, it had a strange sound, striking the ear with a somewhat unmusical thud. Nevertheless, I dutifully entered the house, where my parents were sitting in the living room: Mom, sewing a button on a shirt, and Dad, reading the newspaper. “Mom and Dad, what does ‘____’ mean?” The next ten seconds went by in slow motion; Mom halted her needle mid-stitch, and the newspaper slowly descended to reveal the crew-cut pate of my father. “Where did you hear that word?” he asked. “Liam,” I replied, beginning to catch on that I might have been the victim of a set up. Mom took the ball: “Timmy, that isn’t a ‘friendly’ word. In our house, we only speak friendly words to people. Do you understand?” “Yes.” “Then go outside and play.” That evening after dinner we were in our pajamas even though the sun was still out, when a most extraordinary thing took place; the doorbell rang. Such an event—sudden and unexpected—never happened at our house. The only explanation we could think of was that the Pope was in town and had stopped by for dessert. Actually, it was Liam and his dad. The sight of the five of us kids crowding around the door calling “Hi, Liam!” deepened the shade of the boy’s blushing cheeks to a crimson red. My father stood outside the door, speaking to his neighbor in hushed tones. After a few moments, he looked down at Liam, shook his hand, and father and son returned home across the street.

I never quite understood the meaning of these events until many years later, and certainly the semantic content of “____” was never shared with me that summer’s day. (One wonders: does “____” have a meaning? It can act as almost any part of speech, especially when “-ed,” “-er,” or “-ing” is affixed to it. People use it for many purposes, though not usually “friendly” ones. More often than not, it is the hallmark of the uncouth who find it difficult to articulate their anger or frustration in a civilized manner.) Yet one thing was clear to me as a five-year-old boy, even if it remained implicit. Words matter. They can make friends or generate enemies, they can soothe or sting, and they can reveal the truth—or conceal it.

We live, dear brothers, in a society that is increasingly coarse, though not exclusively because of obscene language. In the past, a writer had to go through the process of putting pen to paper, writing in complete sentences, proofreading and polishing, signing, addressing, stamping, and dropping a letter into the mailbox. This afforded him dozens of opportunities to rethink, edit, and omit statements with second or third-order effects. Things are very different now. Various forms of social media allow individuals to post personal thoughts and feelings instantly through cyberspace, however half-baked, thoughtless, or cruel they may be. Indeed, language itself is violated hundreds of times a day. The majority of English teachers weep for the impending “death by a thousand cuts” of their mother tongue: mangled grammar, dangling participles, misspellings, incorrect punctuation, split infinitives, disagreement between pronoun and antecedent, and, yes, the ubiquitous “emoji.” Some, however, contribute to the chaos by retreating from the struggle to preserve standards. They argue that speech is an “evolving organism,” in which case the very frequency of linguistic misdemeanors is evidence that such language is now “acceptable.”

This, my friends, is the cultural landscape in which seminarians prepare to serve the Church. Remember: to will the ends is to will the means; men who would be the ministers of God’s word must develop “intellectual” virtue and, more specifically, an appreciation for the power and beauty of language. To do so is to build bridges between people, and to humanize a public arena that seems more and more uncivilized by the day. Such was the case with a fifth-century ex-slave who eventually returned to the land of his captivity to heal it by his gentleness and refinement, even as Europe went into decline. As Thomas Cahill writes, St. Patrick “found a way of swimming down to the depths of the Irish psyche and warming and transforming Irish imagination—making it more humane and more noble while keeping it Irish.”

I appeal to you, then, not as a victor of the cultural conflicts fought on sacred, secular, and soldierly battlefields: far from it. Rather, I speak as a happy warrior who attempts to learn from his countless mistakes: some honest, others cosmetic, and still others truly boneheaded. In my fallible opinion, there is no greater priority for the Church today than the cultivation of its priests and, specifically, seminarians at the college level. If physicians learn to respect the dignity of the human body; accountants, money; and soldiers, military force; so too the priest of today must show respect—and indeed, love—for language, in all its music and fire. He must know what to say, how to say it, and, at times, when to refrain from speaking altogether. He knows that the “naked truth” often leaves a bleeding victim in its wake, whereas the truth spoken in love can give human beings a new lease on life, a different perspective on their suffering, and a medium through which “heart speaks unto heart” (the motto of John Henry Newman). Most importantly, he knows the difference between the words of men and the Word of God. The confusion of the two has produced incalculable, unnecessary damage, while their distinction can produce peace and edification. In the pages ahead, I hope to explain the mission and content of the college seminary, namely, philosophy in the service of theology. Following this is a discussion of various forms of language that assist the priest in everyday conversation, spiritual direction, the confessional, and the pulpit. Along the way, I may offer anecdotes that recount a minor success or major blunder on my part, in hope that the latter may not be repeated.

Philosophy, the Handmaid of Theology

Christianity makes a real distinction between two disciplines in search of ultimate truth: philosophy (“the love of wisdom”) and theology (“God-talk”). St. Thomas Aquinas rightly calls the former ancilla theologiae (“the handmaid of theology”), inasmuch as it prepares people for a meaningful conversation about the subject to which all other arts and sciences ultimately point: God. Philosophy accomplishes its task in two ways. First, it equips the mind with the necessary language and categories to analyze human experience clearly and precisely. Moreover, it raises the perennial issues that have confused, confounded, and otherwise captivated human beings from all cultural and religious backgrounds. Pope John Paul II (Fides et Ratio) lists some of these themes: “Who am I? Where have I come from and where am I going? Why is there evil? What is there after this life?” To be sure, intelligent people from all backgrounds who seek the truth can advance the dialogue and arrive at legitimate, however provisional, answers to these questions. In the end, however, philosophy elicits from the mind a thirst that only theology can quench.

The great privilege of contemplating the essence of God belongs properly to theology. To touch—or even point to—the mystery of God, is to gaze, if for a moment, on eternal Truth, to call attention to the Divine Word, even if by stammering in the words of men. The value of Christian theology lies precisely in the fact that it does not rely solely upon reason. Theology establishes a dynamic relationship between the intellect and a special, God-given gift not everyone enjoys, i.e. faith, the “assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Heb. 11:1).

Both philosophy and theology dedicate themselves to the attainment of truth, even if they diverge in their methods: philosophy, through the exercise of reason unaided by faith, and theology, defined by St. Anselm as “faith seeking understanding” (fides quaerens intellectum). In the end, there is no quarrel between the “handmaid” and her “queen.” While the task of philosophy—reasonable certainty in the existence of God, the source of all being and perfection—is a noble goal, it only goes so far. Just as mathematics seems to have a “cold, austere beauty” for Bertrand Russell, so too the God of the philosophers comes across as infinite yet inaccessible, uninvolved in the lives of real human beings. Christian theology, by contrast, ponders faith in a personal deity. It contemplates the God and Father of Jesus Christ, the source of all love and compassion, who reveals himself in the course of human history. This is the God that reason alone can never discover.

Reason’s partial attainment of truth, however, whets the appetite of the soul for the Source of Truth that paradoxically transcends the mind. It is arguable, then, that the primacy of theology in the order of being implies that of philosophy in the order of time. By not presuming faith on the part of the interlocutor, the priest with a philosophical outlook helps his flock—saint and sinner, believer and non-believer—to make sense of the questions that underlie human experiences, from the joyful to the tragic, and once prepared, to search God’s Word for answers. As pastors of souls, Roman Catholic priests enjoy a tremendous practical advantage that many of their colleagues lack. With all due respect to Bible study, people do not normally approach priests with explicitly Scriptural questions, say, the Synoptic problem, or the implications of translating the Greek word ἄνωθεν as “again” or “from above.” Moreover, people resist the cleric who tends to steer the conversation toward ready-made answers, or sacred texts which may or may not be relevant to their circumstances. Rather, people look for intelligent, open-ended discussions with their priest because he has the depth and experience to treat their problems with the care they deserve. Human beings find themselves swept up in the mystery of love (marriage, children) or existence itself (surviving life-threatening peril); they are troubled by the mystery of evil, whether physical (the death of a child) or moral (infidelity, cruelty); and they are puzzled by seemingly outdated ethical conventions (against pre-marital sex, homosexual activity, cloning, suicide). How, then, can pastors best prepare for dialogue with people?

Priests do well to remember that the degree of explicit, religious faith among the people they serve can vary wildly. Within Catholicism, a widow who regularly experiences mystical union with Christ shares the pew with her 16-year-old grandson who, however intelligent he may be, is completely unchurched. As for those outside Catholicism, consider the fact that, in the military, the religious preference with which the largest number of personnel identifies is: “no religious preference.” A priest makes the care of all these souls his responsibility. This begs the question: how does one reach out to all? Admittedly, the best, most profound answers to the questions of the mind, and the most satisfying assurances to the yearnings of the heart, are found in the Christian Scriptures and Tradition. The problem, however, is that many are not yet “ready” to hear the message of the Gospel; indeed, secular culture makes it fashionable to put oneself “above” Christianity, to declare oneself “spiritual, but not religious.” In all too many cases, people fail to connect their “presenting” problems—say, betrayal, grief, and suffering—with biblical solutions, such as forgiveness, hope, and resurrection. Should the priest, then, absent himself from the conversation until the individual evinces some degree of faith? On the contrary, a good pastor listens to people and asks questions to encourage deeper reflection on these presenting problems, thereby preparing the soul to hear the voice of Christ in the Scriptures. This requires tremendous commitment, but the rewards are great.

Two examples of “preparing” the soul can help. The first comes from Plato’s Republic (518b), in which Socrates explains his idea of enlightenment. For him, genuine education is not a matter of simply transferring knowledge from one mind to another, but of directing the attention of the mind to the eternal, stable realities (“universals”) that lie behind individual things in the material world (“particulars”). Various studies, particularly mathematics and philosophy, train the mind to think abstractly, thereby “lifting” the soul to the intellectual realm where it can ponder these timeless truths. Education must ensure that the “eye of the soul” is “turned around from the world of becoming, until the soul can contemplate the essence and the brightest region of being: the Good.” Obviously, Plato did not possess Christian faith, but he was aware of a transcendent world, one with which most people are unfamiliar. Catholics understand the “World of Forms” as an imperfect anticipation of the Christian notion of “heaven.” Plato’s mindfulness of this realm is his gift to the priest. (He can perhaps be forgiven, then, for downplaying the importance of the material world, and the flesh-and-blood people whom Christ, by his Incarnation, redeemed.)

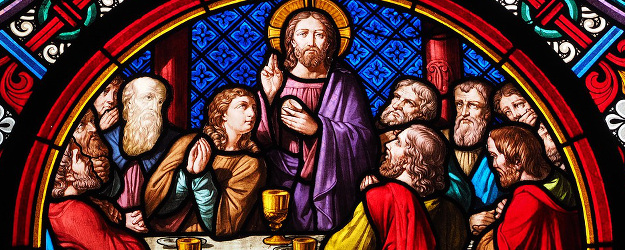

Christian art expresses the importance of profane learning in, among other places, the south arch of Chartes Cathedral in France (12th century), where the child Jesus rests on the lap of his mother, the “Seat of Wisdom.” Why does the church feature representations of secular learning (grammar, poetry, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) on the exterior of the House of God? These seven “liberal arts” are precisely that; they “free” the souls of human beings, who then enter the sacred space where the divine presence washes over them. According to Phillip Ball, Christians must be willing to discover truth wherever it presents itself. So too with the priest who “touches the divine” every time he speaks with his people. He employs secular studies, not to be a know-it-all, nor to tell others what to think, but rather that he might be informed and attentive to the parishioner who comes to him with an “affair of the heart” or other serious concerns. By means of those first three “language arts” (trivium), the priest becomes an articulate, interesting, and engaging partner in conversation, while through the next four “numerical arts” (quadrivium) he becomes more thoughtful, sensitive, and insightful. In the end, a priest’s secular education is designed so that, far from inserting himself into the situation, he may actually “get out of the way” in the exchange between God and the individual. In place of announcements and assertions, he prefers questions and suggestions, listening carefully to discern the movement of the soul.

What explains, then, the virtual absence of philosophical training from the formation of non-Catholic clergy? Its rejection may come from a certain reading of Colossians 2:8: “See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deception, according to the tradition of men . . . rather than according to Christ.” Interestingly, one of the great minds of Reformed Christianity—John Calvin—points out that Paul does not condemn philosophy as such, but only those forms of sophistry that favor persuasion over truth. Nevertheless, philosophy as a propaedeutic to the sacred sciences is not common in much of Protestant Christianity. The Catholic mind, by contrast, sees no contradiction between the two, nor does it dilute, modify, or substitute the power of the Gospel by the study of philosophy and secular learning. Instead, it draws a connection between the saving message of Christ and the natural, collective wisdom of culture, just as St. Paul does at the Areopagus (Acts 17:16–34). He acknowledges the pagan belief in an “unknown god,” and even cites the Greek poet Epimenides (Cretica), that “in God we live and move and have our being.” Where does one find that connnection? Leisure.

Leisure and Language

The suggestion that college seminarians have “better things to do” than engage in leisurely activity is ignorant at best, and harmful at worst. On the contrary, seminarians and priests must be men of leisure, in the best sense of the term. The summer before our freshman year in college, Fr. Dietz and Fr. Klein had us read Josef Pieper’s 60-page essay, Leisure, the Basis of Culture. One rarely finds a book of any length more enlightening. As Pieper masterfully explains, “leisure” (σχολή=schola=school) is neither idleness nor sloth, but the activity one pursues for its own sake, without respect to practical use or profit. In other words, leisure is what one “gets” to do after completing what one “has” to do. In antiquity, the aristocracy looked to others to supply their material needs, which freed them to pursue more “leisurely” interests, including the intellectual life, theater, and gymnastics. Together, the liberal arts and public worship (cultus) had the effect of freeing, nourishing, and otherwise “cultivating” the soul, thereby making possible a worthwhile life, not just survival. Of course, one might argue that study can have a practical use, i.e., preparation for a career or training in a skill, but to this extent it is servile, not liberal, in nature.

Citing Aristotle, Pieper recommends that we should “be un-leisurely (i.e., we must work) in order to be at leisure,” not the other way around. It follows, then, that the “work ethic” so prevalent in our time actually has things backward. All activity, from higher studies to professional sports, has been tainted by the need for an external reward, and popular attitudes toward formal education only confirm this. All too often, students think of school as a necessary evil, a drudgery, a “means-to-an-end” that secures their “true” desires: scholarships, degrees, jobs, material wealth and, perhaps, even fame. In light of this, the formation of the college seminarian (one can only hope) seems counterintuitive; the program he follows is designed to turn the eye of his soul to the realities that matter most precisely because, unlike material things, they endure forever. One recovers the sense that study is a joy to be savored, not endured; that sport is both an exercise of the body and a metaphor for life itself; and that worship of almighty God is the highest imaginable form of love.

In a famous commencement address, Edmund Pellegrino, MD (former President of Catholic University and bioethicist), famously distinguishes between simply “having a degree” and “being educated.” He articulates several qualities that typify the liberally educated person: intellectual initiative, critical thinking, insight, facility of self-expression, principled commitment, reasoned judgment of beauty, and independence of thought. Yet the metaphor he uses—education as a benign “virus”—continues to delight and challenge students of our time. He writes: “The degree you receive today is only a certificate of exposure, not a guarantee of infection. Some may have caught the virus of education, others only a mild case, and still others may be totally immune.” In a word, liberal education “infects” the soul with a love for truth and goodness, and its symptom is the well-lived life.

This being the case, the stakes of liberal education for the priest of our age could not be higher. How often do Catholics rightly complain that they come away from Mass “unsatisfied”? Of course, faithful Catholics know that the reception of the Eucharist is of paramount importance, but its meaning for their lives is often ill-served by long, disorganized, pointless, and poorly delivered homilies. Preaching of this sort is disrespectful to parishioners, all of whom deserve a thoughtful message, and many of whom are themselves highly educated. Seminaries, then, must choose whether to produce the nice-guy priest who knows just enough to be dangerous, or Chaucer’s Parson, whose knowledge of Christ and the human condition equip him to nourish and protect his flock:

A holy-minded man of good renown

There was, and poor, the Parson to a town.

Yet he was rich in holy thought and work.

He also was a learned man, a clerk

Who truly knew Christ’s gospel and would preach it

Devoutly to parishioners, and teach it. (Canterbury Tales, 487–92)

The cultivation of a priest like this is an enormous task, given the relatively brief, eight-year period that comprises both collegiate and theological studies. Admittedly, intellectual training is but one of four “pillars” of priestly formation, the others being “human” (psychological health and social skills), “spiritual” (prayer life and mature faith), and “pastoral” (service to the Christian community). That said, a certain fluidity exists among these pillars, and seminaries do well to organize their priorities, given the individual needs of candidates.

In its Program of Priestly Formation, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops explains the educational disadvantages with which many individuals approach the seminary. These include a lack of exposure to the humanities, poor study skills, inadequate facility with the English language, and uncritical thought that mirrors the defective epistemologies and moral biases of secular culture. The effort and attention required to overcome such obstacles could take up every minute of those eight years, but obviously the seminary is not “just” a school. Nevertheless, equality of emphasis is not the same as equality of time devoted to each pillar. The bishops wisely point out that pastoral experiences—teaching, retreat work, Bible study, hospital and youth ministry, prayer groups, etc.—are important, but in the right measure: “The pastoral formation program should be an integral part of the seminary curriculum and accredited as such, but none of its elements should compromise the two years of full-time pre-theology studies or the four years of full-time theological studies.” (Program, 83) This prescription holds true especially in the case of the college years.

Eloquentia Perfecta

The practical implications of intellectual formation are considerable, especially if study is thought to be leisurely activity and not just the price one pays for ordination. Priests should love and delight in words, to say nothing of their devotion to the Divine Word. Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Austrian philosopher of language, famously remarked that “the limits of my language are the limits of my world.” If a man is accepted into the seminary, he deserves every opportunity to broaden his world and satisfy any deficiency that prevents him from becoming an effective minister of God’s Word. Time and resources must be made available to overcome learning disabilities, to promote verbal skills (especially reading and writing), and, if possible, to train himself in biblical and modern languages. Beyond this, exposure to different forms of language—prose, poetry, drama, song, rhetoric, and “eristic” (philosophical conversation)—contribute to “ease” of language, or facilitas. According to St. Augustine, verbal fluency is the hallmark of the priest who knows how to teach (educare), delight (delectare), and persuade (movere) his people, and thereby introduce them to the Divine Word. (De Doctrina Christiana) Once he masters these disciplines in those precious years of formation—including summer vacation—then perhaps the college seminarian can take a part-time job, or teach CCD, but until then?

Future priests do well to learn that, when one ascends the pulpit (or, as liturgists insist, the “ambo”), he is to preach the Gospel—and that alone. This is much more difficult than people think. Priests often fall victim to the misguided notion that they must “entertain” their congregations or, perhaps more dangerously, inject their own views—political or otherwise—into their homilies. Bill C. Davis satirizes this inclination in his Broadway play Mass Appeal, in which an earnest, tone-deaf, and shallow Deacon Mark is paired with a glib, “appealing,” but equally shallow pastor, Fr. Tim Farley. Exasperated by the young man’s insulting attitude and superficial message, Fr. Farley remarks without irony or self-awareness, “It is no accident that the collection comes after the sermon. It’s like a Nielsen rating . . .” We know, of course, that financial return should never be the guiding principle when preparing a sermon, in content or style. On the contrary, the responsible preacher operates out of a nobler purpose: to draw attention to the mystery of the Triune God and thereby encourage genuine virtue. This quality typifies the sermons of St. John Chrysostom, the “golden mouth” who admonished prince and pauper alike with eloquent—and elegant—comparisons, to wit: “If you cannot find Christ in the beggar at the church door, you will not find Him in the chalice.” The priest, then, must perform a brutally honest—and consistent—check on his motivation well before ascending the steps of the sacred platform, to ensure that the words he speaks are what people “need to hear, the things that really help them.” (Eph. 4:29) He does so by asking himself a simple question: “Exactly whose needs am I addressing?”

This self-less attitude that genuinely seeks the good of others demands that future priests dedicate themselves to the craft of good writing. I learned the need for effective verbal communication, while not attaining it, during freshman English with Fr. McManus, who returned my 2-page reflection paper with three pages of commentary and corrections. Of course, criticism can sting, but it can be salutary as well. The artistry of a well-structured sentence that engages and inspires is a tactic by which the man of God “speaks the word people need to hear.”

Vulgarity, Volume, and Voicelessness

This essay recounted the introduction of a young boy to a word that makes its way all too often into public discourse. Sad to say, such language extends to professional environments as well. At a staff meeting some time ago, the commanding officer of the all-male cavalry squadron asked the chaplain for his “word of the day”: a short inspirational message for the edification of the leadership. In my remarks, I called attention, as gently as I could, to the possibility that various “word-bombs” can be forms of intimidation that erode unit cohesion over the course of time. After the minute-long exhortation, the commander—a brilliant and effective leader—responded with a gleam in his eye: “Thank you, Chaplain. That was a ‘___’-ing awesome ‘word of the day!’” It was a great response that brought down the house, but I wondered whether it undermined the message. Sometime later, a young officer at that meeting found himself leading a convoy through the streets of Baghdad when his boss was away; he was bothered by the constant barrage of word-bombs he heard via headset among his more experienced troops. He could have simply ordered his subordinates to refrain from vulgarities, but since he was yet to earn their respect, he decided on a much more difficult course of action. He simply did not participate in crude conversation, and his silence was deafening. After just one convoy, a young enlisted soldier asked him, “Sir, are you, like . . . religious or something?” When the commander returned two weeks later, he was amazed by how elevated the level of conversation among his men had become.

In my experience, the worst aspect of bad language—not to mention shouting—is not just the vulgarization of public discourse, troubling as this may be. No: the worst part is that it completely shuts down the conversation. Priests know that when counseling married couples, the moment they engage in loud or abusive language, the dialogue is already at an end. Allies immediately transform into adversaries, and it is better to end the exchange then and there. Why? The shock value of bad or even “charged” language (“Why did you . . . ?”) only raises the emotional temperature of a discussion, diminishing the light that it might otherwise have shed on the subject. Such meetings should always begin by setting the terms of the conversation with the people involved. As for the priest himself, it goes without saying that vulgarity has no place in the pulpit (although, sad to say, this happens from time to time). Yet even suggestive, silly, or undignified language puts distance between the shepherd and his flock. It is not of God: priests are well advised never to engage in it.

Read, Read, Read

Our teachers used to tell us that we don’t have enough time to read good literature; we only have time to read the best. One of the great lessons I took from the seminary (both college and the theologate) is that the best insights into the ways of grace are found, not just in works of theology, but also in literature accessible to ordinary readers. Whether Fr. Catania directed us in Graham Greene’s The Potting Shed, or Fr. Kohli waxed eloquent on the subject of Catholic novelists (Evelyn Waugh, Francois Mauriac, J.R.R. Tolkien, Georges Bernanos, Flannery O’Connor), one got a sense that stories—not systematics—evoke an immediate sense of the divine. Likewise, Fr. Viladesau, in the introduction to his theology classes, always paired a passage from the Scriptures with another from literature. One of the most powerful was from T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, a popular telling of the Arthurian legend. At one point, Lancelot tries to explain to Arthur and Guinevere why his son, Sir Galahad, lacks what people today call “social skills.” After years of searching for the Holy Grail, he is unused to idle chit-chat, not out of contempt for human beings, but because he has been preoccupied by another, more profound, conversation:

Arthur, you mustn’t feel that I am rude when I say this. You must remember that I have been away in strange and desert places, sometimes quite alone, sometimes in a boat with nobody but God and the whistling sea. Do you know, since I have been back with people, I have felt I was going mad? . . . A lot of the things which you and Jenny say, even seem to me to be needless: strange noises: empty. You know what I mean. ‘How are you?’— ‘Do sit down’— . . . What does it matter? Where I have been, and where Galahad is, it is a waste of time to have ‘manners.’ So you can understand how Galahad may have seemed mannerless . . . He was far away in his spirit, living on desert islands, in silence, with eternity.

That class, almost 40 years ago, inspired me to read the entire 600-page book. I remember—and recommend—this passage constantly, especially for people who are tongue-tied trying to find adequate language to describe God’s activity in their lives. Of course, a spiritual director can use expressions like via negativa, or “Dark Night,” or “rules for the discernment of spirits,” or any other kind of technical jargon with the souls who come to him for guidance. Sometimes, however, it is enough simply to know that one is (almost literally in this case) “in the same boat” as the mystic, for whom silence best expresses divine sublimity.

On the other extreme, what of those who approach their confessor, not only to atone for their sins, but to describe a state of genuine spiritual anguish? They are not actually abandoned by God, but they certainly feel that way. There is a poignant moment in Evelyn Waugh’s masterpiece, Brideshead Revisited, that involves Cordelia, the spiritual “heart” of an English Catholic family. She describes an occasion sometime before, when a priest came to remove the Eucharist from the house chapel, after which it appeared to be just another oddly decorated room. Using the language of the Tenebrae (“shadows”: from the Book of Lamentations) service, she expresses her spiritual desolation at the time: Quomodo sedet solo civitas (“How lonely is the city”). This “absence,” moreover, is comparable to the spectacular defections of her father, brother, and sister from the Faith. Still, Cordelia the mystic is confident that even profound loss is not the last word on her family. She quotes, of all things, a popular novel by Chesterton.

Anyhow, the family haven’t been very constant, have they? There’s [Papa] gone and Sebastian gone and Julia gone. But God won’t let them go for long, you know. I wonder if you remember the story mummy read us the evening Sebastian first got drunk—I mean the bad evening. “Father Brown” said something like “I caught him” (the thief) “with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

True, the “lost” characters have gone far astray by various kinds of weakness (2 Cor. 12:10), yet all of these finally yield to the healing power of God. By the end of the novel, Cordelia’s prophecy is vindicated.

None of this is to say that the priest has to compile a mountain of “proof texts” suitable for any spiritual occasion. Yet great literature can express unique spiritual states that resonate with readers who cannot otherwise put their finger on the movements of the human soul. Jesus says (Matt. 13:52) that the scribe “learned in the kingdom of heaven is like a head of a household who brings out of his treasure things new and old.” The best advice for a priest to ensure he has sufficient supplies with which to nourish his flock is: read, read, read. He may have to explore his entire stock in order to find the necessary provisions for just one soul in need.

For Heaven’s Sake, Know Your Audience

It’s one thing to love baseball; it’s another to wear your Yankees T-shirt to Fenway Park. Likewise, the priest must remember that certain cultural references that succeed with one congregation may backfire with another; far from elucidating a religious truth from the Scriptures, they may actually obscure it. During graduate school, I lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, at a parish that housed the chaplaincy for Columbia University. It was an exciting time of intellectual stimulation and cultural enrichment. The trouble was that, for every subject I might address in the sermon, there was at least one PhD in that field sitting in the congregation. The pastor of the parish, Msgr. Maloney, was a highly educated cleric who could easily speak the language of academics. I? Not so much.

One July 4th weekend, I was looking for a literary passage that might express a sense of patriotism. I chose Shakespeare’s “St. Crispen’s Day” speech (“We few, we happy few”) from Henry V. What a great piece. The Battle of Agincourt was, of course, a turning point in the bloody 100 Years War pitting England against France. Kenneth Branagh’s performance of this monologue is terribly affecting, but for some reason the congregation that day seemed oddly unmoved by mine. After Mass, a gentleman from the congregation—as it happened, a dean from one of the colleges with a doctorate in European history—asked to speak with me. Oh: did I mention that the name of the church was L’Église de Notre Dame? It was built in the early 20th century for French-speaking Catholics in New York City, complete with the Grotto of Lourdes behind the altar, and statues of the Little Flower and the Maid of Orleans, who was but two years old when the Battle of Agincourt took place. The professor, in very kind language, alerted me to the masterpiece of obtuseness I had unleashed on the congregation: “Father, at that moment I looked toward the tabernacle guarded by St. Joan of Arc, and I could swear I saw her weeping . . .” I had effectively celebrated one of the darkest chapters of French history, a disaster of unmitigated proportions, in a church with French roots. My point: know your audience. Not only will you avoid giving unnecessary offense, but it will force you to do your homework.

If You Write the Songs, You Rule the City

No doubt a musical sensibility, understood in the broad sense, can be enormously helpful for those who preside at the sacred liturgy. Josef Pieper speaks of an inner “dynamism” within man toward the Good, something he can never attain in this life. Man is a work in progress, and the art form that best expresses the temporal element of his nature—that he “is” to the extent that he “becomes”—is music. Indeed, whether vocal or instrumental, music is necessary when “the spoken word proves utterly inadequate.” When sacred music is done well, it expresses man’s gradual “self-realization,” and the confluence of joy, sorrow, confusion, struggle, and hope that mark his journey toward heaven. When done poorly, or in such a way as to draw attention to the musician, music dulls the soul and keeps it earthbound.

This is not to argue that the priest himself must demonstrate advanced musical proficiency (even though, according to the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum, this would make him “perfect”). Yet he should develop an ear, not only for beautiful music, but for the true and profound thoughts it enshrines. John Dewey (Art as Experience, 463) rightly points out that, from its earliest days, “music” was by definition the combination of melody, harmony, and “cadenced (or rhythmic) speech”: in a word, song. It follows that the sacred songs—whether chants, psalms, hymns, anthems, or motets—which comprise liturgical music should be judged for their poetic and theological virtues, as well as for the delightful sound structures that strike the ear. There is much to say about the inconsistency of Roman Catholic liturgical music today: some of it sublime; much of it execrable; most of it spectacularly banal. For the purposes of this essay, however, it is enough to ask that the priest cast a critical eye on the words of today’s liturgical hymnody, and act accordingly.

That both the content and comeliness of words are as important as a song’s melody first occurred to me as a college student in the 1970s, when young Catholics were in thrall to popular versions of the Gospel, most notably Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar. Right about this time, we were reading selections from the Republic (377b) with our teacher Fr. Dietz, who explained to us Socrates’ censorship of the arts. Plato’s rationale for banning certain artists was not a matter of contempt for them. On the contrary, he was keenly aware of the expressive influence that “image-makers” wield, from poets to painters, from sculptors to musicians. The problem was that the emotional power of art often militates against reason. To this extent, art can actually obscure or even distort the truth. As a case in point, Fr. Dietz offered a critical analysis of a soliloquy from Superstar in which Jesus undergoes his Agony in the Garden:

God, thy will is hard.

But you hold every card.

I will drink your cup of poison

Nail me to your cross and break me

Bleed me, beat me, kill me!

Take me now, before I change my mind!

Fr. Dietz explained that, catchy tunes and showmanship aside, this portrait of a deity bears no resemblance whatsoever to the God of Christianity. Indeed, this song paints the picture of a manipulative sociopath toying with a co-dependent child and taking delight in his demise.

The liturgical presider with theological and pastoral sophistication owes it to his parishioners to scrutinize the choice of the hymns they sing at Mass. The problems with songs in the current Catholic repertoire are legion. However tempting it may be to mention them by name, it is simply not worth incurring the wrath of liturgists; rest assured, many of these songs are among the most popular currently in use. Some are not even Catholic in origin, but dreary, “Jesus-and-me” ditties reeking with overwrought emotion. Others are actually pop songs antithetical to Christian belief. Some are almost completely inane, though what they lack in coherent thought they make up for in cloying sentimentality. Others flirt with blasphemy, from Pelagianism to the denial of the Real Presence. (I say “flirt,” for in truth, they are far too vapid to rise to the level of actual heresy.) Perhaps the most tragic are compositions whose flaws are not so much theological as anthropological. How long must Catholics be forced to sing hymns that describe them as delicate, immature children so scared of the dark that God has to come and “cradle” them with love? Such dreck deserves the same withering critique that Dietrich Bonhoeffer directs at certain members of the Christian clergy. According to Bonhoeffer, these religious forces “demonstrate to secure, happy mankind that it is unhappy and desperate and unwilling to admit that it is in a predicament about which it knows nothing, and from which only they can rescue it.” Of course, Catholicism recognizes the wounded condition of human beings. At the same time, they are also the imago Dei, the “image of God,” whose inherent dignity lies in their dual capacity to think and love. The Gospel can only challenge the disciples of Christ, whatever their frailty and limitations, if they can face God as mature adults, not clueless children.

Accordingly, the good pastor knows how to choose high quality liturgical song, with graceful melody, rich harmony, regular rhythm, poetic beauty, and theological insight; music of this sort can, in the words of the old spiritual, “heal the sin-sick soul,” providing it with an array of poetic imagery that imposes divine order just as it delights. Conversely, he avoids the music I describe in the paragraph above, for its potentially lethal effects on the same.

Ordinary Words, Primordial Words, and the Divine Word

In the introduction to this essay, I discussed the distinction between the words of men and the Word of God. Actually, among the words of men, a further distinction is necessary: ordinary words, or language with a utilitarian purpose; and primordial words, or concentrated language. According to Karl Rahner (“Priest and Poet,” 296–305), people “use” ordinary words to conduct their everyday affairs. Primordial words, by contrast, are so dense in existential truth as to be comparable to a living being. They are “children of God” who reveal man to himself, and any attempt to analyze or define them would yield the same result as dissecting a living organism in a laboratory. Rahner further points out that, all too often, people confuse “ordinary” words with “realistic” ones, as though the literal, face-value of speech were its most important aspect. Who, he asks, best captures the meaning of the word water? The chemist, for whom the term indicates a molecular compound? Or St. Francis, for whom it is the means of life, both natural and divine?

Just as stone is the material of the sculptor, and sound, of the musician, so too primordial words, and the ideas they express, are the stuff of “word-art,” or poetry. Primordial words are the language of mystery, in which the “soft music of infinity” echoes within human beings. For Rahner, their outstanding, albeit paradoxical, characteristic is “luminous darkness,” which both points to and conceals the divine essence.

It may take the priest an entire lifetime to become fluent in the language of mystery. Yet strictly speaking, the responsibility of the priest qua priest is different from that of the poet. Citing the New Testament, Rahner argues that the priest’s main responsibility is not to speak his own word, however profound it may be. Rather, he is the minister of the efficacious Word of God, Who became incarnate in Christ, and Who continues to speak in the Scriptures and Tradition of the Church.

The practical implications of Rahner’s theology of the word are significant. For one thing, it means that priests have no business prancing around the Church with a microphone, “Oprah-style,” as the Mass is not a talk-show. There is a reason priests ascend the steps of the pulpit, incense the Gospel book before reading from it, and preach from an elevated platform. Likewise, the way priests pray the liturgy itself, particularly the words of institution over the Eucharistic elements, is of vital importance. By speaking clearly, distinctly, and reverently, they acknowledge the dignity of the sacred mysteries, among which they act in persona Christi. In short, the priest ought never to lose his sense of responsibility: the weighty, awesome burden that falls to the steward of divine grace, which is always greater than himself.

There are, of course, a few extraordinary individuals capable of speaking as both priest and poet, one of whom is the Victorian-era Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins. It is said that Hopkins did “poorly” in theology, not because of intellectual ineptitude, but because his theological views reflected the influence of John Duns Scotus. These were at odds with the prevailing Thomistic approach to theology, according to which the mind knows universals, not particular things. Against this notion, Scotus (De Anima) proposes the idea of haecceitas (“this-ness”), according to which the mind can arrive at some knowledge of particular things. Without the intuition that “this” is different from “that,” the intellect cannot understand quidditas (the “what-ness” of things). In light of this idea, it is little wonder that Hopkins seeks the presence of God, not in the abstract, but in concrete, individual realities. His poem, “God’s Grandeur,” describes creation, injured though it may be by human activity, as yet the mirror of the divine: “And for all this nature is never spent / There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.” Moreover, in “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” Hopkins gives voice to non-human creatures as well as people:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

Elsewhere, Hopkins the priest speaks in the name of Christ. In what is for me his most moving poem, “The Soldier,” a nation’s guardian, in all his nobility and manhood, becomes a metaphor of divine graciousness.

Mark Christ our King. He knows war, served this soldiering through;

He of all can reeve a rope best. There he bides in bliss

Now, and séeing somewhére some mán do all that man can do,

For love he leans forth, needs his neck must fall on, kiss,

And cry ‘O Christ-done deed! So God-made-flesh does too:

Were I come o’er again’ cries Christ ‘it should be this’.

Few priests can speak with the voice of a poet. Still, they should be able to understand his language, and speak in such a way as to suggest that the holy communication between human beings and God at Mass is its own reward, with no utilitarian “payoff” beyond itself. For this reason, one hopes that congregations will be patient with clerics when we use our “priest-voice”: the somewhat affected tone and cadence that makes our “being-in-the-moment” pellucidly clear to everyone. Having been forced to listen to my own voice over the years—and being so appalled as to take steps to improve it—I hope our congregations will trust that our hearts are in the right place; we are simply trying our best to respect the dignity of the occasion.

Final Tips

Brothers, I end my remarks with three brief suggestions—all from the great Dominican priest Fr. A.G. Sertillanges—that might strike you as counter-intuitive.

1) In light of the tremendous responsibility described above, you might think you have to spend every waking moment at your desk or in the library. Not so. Consistency and quality of effort, not quantity of time, are integral to academic achievement. It is unrealistic for an athlete to maintain an 8-hour-a-day workout schedule for his entire life. Likewise, the seminarian must adopt a reasonable horarium, especially if he expects himself—and he should—to continue with his studies as a priest. Fr. S. asks: “Do you have two hours a day?” If you give the best of yourselves in that timeframe every day, you will prevail. And don’t use not-being-a-genius as an excuse to avoid getting your hands dirty in study; as Fr. S. tells us: “Genius is long patience.”

2) Do you know how people take it as a compliment to be called “intellectually curious”? They shouldn’t; it isn’t. An intellectually curious student is the academic equivalent of a child who runs toward the bright, shiny object in front of him, only to discover too late that it is an open flame, or a bridegroom who exits the church hand in hand with his bride while checking out the maid of honor. This temptation toward intellectual curiosity is dangerous; don’t indulge it. You already have more than sufficient material to occupy your full attention; anything else is from, let’s say, the “Naughty” One.

3) This a corollary of the second. You needn’t pander to curiosity because, if you really are faithful to the search for truth, all things worth knowing will eventually come into view. Fr. S. quotes Van Helmont: “Every study is a study of eternity.” For the Catholic, to know even a small part of the Truth—really know it, that is—is to grasp the Whole on some deep, undeniable level.

Conclusion

There is a form of asceticism (or is it mysticism?) unique to seminarians. Yours is not, at least not yet, the life of public, full-time ministry, with all its challenges and rewards. No: yours is the unsung, often unnoticed, spirituality of academic life and religious preparation, wherein you demonstrate genuine love today toward those you will not meet for another decade—or more. That’s tough; but for those called to it, it is precisely what makes the life of a priest so good, so loving, so wonderful. Delayed gratification, and yes—suffering—are the means by which the power of the Cross softens the hard heart, and makes the loveless lovely. When you finally show up at the parish, you’ll be ready to speak God’s Word in both the triumph and tragedy of people’s lives; both can be moments when grace turns the eye of the soul to what really matters.

Bibliography

Augustine. De Doctrina Christiana.

Ball, Phillip. Universe of Stone. Vantage, 2009.

Cahill, Thomas. How the Irish Saved Civilization. Anchor, 1996. (p. 161)

Calvin, John. Commentary on Colossians.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. Canterbury Tales, trans. Nevill Coghill Penguin, 2003.

Davis. Bill C. Mass Appeal. Dramatists Play Service, 1982.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Poems and Prose. Penguin, 1953.

Pellegrino, Edmund. “Having a Degree and Being Educated.” [PDF]

Pieper, Josef. Leisure, the Basis of Culture. Ignatius, 1990.

—. Only the Lover Sings. Ignatius, 1990. (pp. 43–44)

Plato. Republic.

Rice, Tim. Jesus Christ Superstar. Wise Publications, 2006.

Sertillanges, A.G. The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods. Translated by Mary Ryan. Washington, Catholic University Press, 1998.

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Program of Priestly Formation. NCCB Publishing, 2006. (pp. 54–55)

Waugh, Evelyn. Brideshead Revisited. Back Bay Books, 2012.

White, T.H. The Once and Future King. Ace, 1987. (pp. 460–61)

Deep, soul searching, profound and from the heart

If the student can achieve this ethos in his studies, he is sure to touch the hearts of his future parishioners. Beautiful.