“…when [Christ] instituted the Eucharist. That fulfilled Jeremiah 31. That’s when he offered what appeared to be bread and wine. That’s when he became a new Melchizedek, feeding the new children of Abraham so that through Abraham’s seed, Jesus, all the nations of the world, all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” – Dr. Scott Hahn

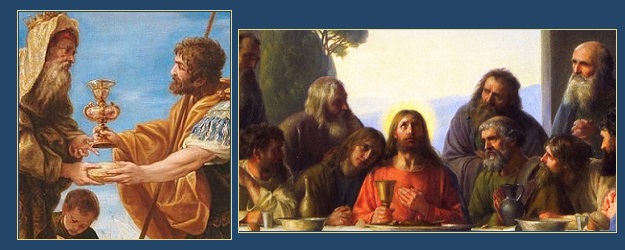

Priesthood in the New Testament is inseparable from the liturgy which it celebrates, and the Eucharistic sacrifice which it offers, in and through its high priest, Jesus Christ. In the Book of Genesis (cf. Genesis 14:18-20), one reads a succinct narrative on the enigmatic character, Melchizedek, who, in the text, is described as a priest of God Most High. He is written as having brought out bread and wine, blessing Abraham (then Abram) who, himself, had returned after being triumphant in battle defeating Kedorlaome, and the kings who had allied themselves with him. Abram, in this encounter, offered Melchizedek a tithe of a tenth of everything (possibly a tenth of everything he owned). After this, nothing else is written of this mystifying character, Melchizedek, in the entire book. Looking ahead in canonical Scripture, then, readers see how Psalm 110:4 recalls the memory of this priest-king of Salem with “solemn words, sworn by God himself who declares to the Messiah-King, ‘You are a priest for ever after the order of Melchizedek’ (Psalm 110:4).”1

Pope Benedict XVI makes a coherent distinction here that, by virtue of this prophecy, the long awaited Messiah was not meant only to be King in the place of the Davidic throne but, also and more so, a priest. It is precisely from this understanding that the inspired author of the Letter to the Hebrews typologically linked, both expansively and expressively, the priesthood of Melchizedek to the high priesthood of Jesus Christ. The Church today reechoes this belief and understanding of the early church. When she acclaims “You are a priest forever” (Hebrews 7:17; Psalm 110:4), she declares the exuberance of her children and the elation of her very body “in contemplating and adoring the Most Holy Sacrament,” for she “recognizes in it the real and permanent presence of Jesus, the Eternal High Priest,” her spouse and Lord.2

A Priest after the Manner of Melchizedek

The words “after the manner of Melchizedek” (Hebrews 7:17; Psalm 110:4), do not simply mean that Christ emulated the act of Melchizedek. Rather, it connotes that Christ was instituting a priesthood that, like that of Melchizedek, did not offer animal blood sacrifices but, rather, a “priestly sacrifice [that] was bread and wine.”3

Dr. Scott Hahn makes the intriguing observation that the Letter to the Hebrews recounts the entirety of the encounter between Abraham and Melchizedek except for one detail—that Melchizedek offered bread and wine. He hypothesizes that this is not an oversight, nor is it a gloss-over, which is insignificant. Instead, he posits that this fact is so crucial, so urgent, that the inspired author presupposes the reader’s comprehension of its importance. This issue of Melchizedek’s sacrifice will be treated later in the article.

Despite many speculations as to his identity, most of the church fathers agreed on the fact that Melchizedek was “a priest of the uncircumcision, a priesthood carried on through Christ.”4 Because of the transitory nature of the Mosaic Covenant, the Levitical and Aaronic priesthoods (both the latter being formed as a punishment unto Israel ensuing the golden calf incident [cf. Exodus 32:4]) were both subordinate to the priesthood of Melchizedek, one reason being that they were exclusive in nature.

St. Thomas Aquinas treats the Melchizedek-Christ typology, quoting how Melchizedek is said to be “without father and without mother and to have neither beginning of days nor end” (Hebrews 7:3). Aquinas states that this is not simply because he truly lacked, or did not have these, but more because Scripture made no allusion to them. In fact, he mentions how Hebrews posits that Melchizedek “is likened unto the Son of God, who on earth, is without father, and in heaven is without mother, and without genealogy,” ultimately concluding that he is most like God in this sense simply because he appears in Scripture, as having “neither beginning nor end of days.”5 This point is imperative when considering that the New and Eternal Covenant necessitated one who would be an eternal liturgical high priest for that Covenant. As such, in dealing with Melchizedek’s priesthood, Aquinas writes that “it was precisely this pre-eminence of Christ’s priesthood in relation to that of the Levites which was foreshadowed by the priesthood of Melchizedek.”6

He continues by demonstrating that because Abraham was the father of Israel, and because Melchizedek received tithes from Abraham, in that act, the whole priestly order of the Old law paid tithes to Melchizedek. As such, Christ’s priesthood is “said to be according to the order of Melchizedek by reason of the pre-eminence of his true priesthood over its symbol, the priesthood of the Law.”7

Melchizedek and the Eucharist

Clement of Alexandria in the Third Century, A.D., was among the first to make the written connection with the bread and wine offered by Melchizedek as prototypes, as elements of the Eucharist. He writes in the Stromata, “Melchizedek, king of Salem, priest of the Most High God, who gave bread and wine, furnishing consecrated food for a type of the Eucharist. And Melchizedek is interpreted righteous king; and the name is a synonym for righteousness and peace.”8

Aquinas states on this issue:

“…in relation to our fellowship in the sacrifice and its fruits, where the pre-eminence of Christ’s priesthood over that of the Old Law principally lies, the priesthood of Melchizedek was a more explicit symbol. For he offered bread and wine, these symbolizing, as Augustine remarks, the unity of the Church, which is the fruit of our fellowship in Christ’s sacrifice. This symbolism is, accordingly, still preserved in the New Law where the true sacrifice of Christ is communicated to the faithful under the appearance of bread and wine.”9

The thesis being hypothesized by Aquinas and, arguably, Holy Mother Church, is that “there is a necessary continuity between the law, priesthood, and sacrifice of the old and new covenants.”10 Nonetheless, the Council of Trent did vehemently and concretely establish that, even within this continuity, there exists a fundamental difference between the priesthood of the old law, and the priesthood of the New Covenant, appealing to the type of Melchizedek for that priesthood. In this light, one can see that the offering of Melchizedek can also be deemed the “sacrifice” of Melchizedek. His “offering of bread and wine resembles more the sacrifice of the altar, than the cross. On the cross, the priest and victim were the same, but in the Mass, the priest and victim or oblation are different, as was the case for Melchizedek.”11 Thus, Christ’s “once-for-all sacrifice on the cross with Christ’s eternal priesthood leads to the assertion that priests of the church continue the priesthood of Christ,” a priesthood that is prefigured in the Old Testament by Melchizedek, by his offering of bread and wine on the altar to God most high, mirrored by countless priests across the generations who offer the same gifts on the altar today in the name of Christ.

The Institution of the Holy Eucharist

Christ’s role as priest-king cannot be fully understood apart from his liturgical action. As such, when the Letter to the Hebrews previews Christ’s priesthood with his Ascension, it demonstrates how his Paschal Mystery underlies his entire priesthood. It was precisely “the process of Christ’s obedience and suffering [that] perfected him so that he could be both a source of salvation and a high priest according to Melchizedek.”12

Old Testament sacrifices were offered exclusively by Levitical priests, yet, in the New and Eternal Covenant, it is clear that “the ministerial priesthood… and the universal priesthood of all Christian believers are both participations in the one priesthood of Christ.”13

Christ alone is the perfect sacrifice as he alone was the spotless, unblemished, new Passover lamb, being Holy and sinless, he offered himself, being both priest and victim, rendering his sacrifice eternally valid and effective. In the celebration of the Holy Eucharist, then, all the baptized come to unite their entire lives with Christ, their high priest forever.

The institution of the Holy Eucharist, amongst other realities, then, was, “the fulfillment by our Lord of the type of Melchizedek, who offered bread and wine…”14

The priesthood that Christ instituted, and which he ordained his apostles into, is “distinct from that of Aaron, [it] is an abiding priesthood, the exercise of which remains in the Mass.”15

In fact, for every celebration of the Holy Eucharist, there is a renewal of the abiding quality of this priestly order. This is because “the priest after the order of Melchizedek abides forever in such a way that he sacrifices after the pattern of Melchizedek; and this takes place invisibly daily in the Mass, when the Church sacrifices his flesh and blood under the species of bread and wine.”16

The Celebration of the Holy Eucharist in the Church

By virtue of that theological assertion, on an ecclesiological level, the Church is cognizant of the veracity that the true Jerusalem, the true Salem of God, is, in its fullest sense, the Body of Christ – the Holy Eucharist is the true peace between God and man. In consequence, when reading the Johannine Prologue, the baptized are made aware that the humanity of Christ is what John calls the tent of God (cf. John 1:14). It was in this human nature, “God himself pitched his tent in the world, and this tent, this new, true Jerusalem is at the same time on earth and in Heaven because this Sacrament, this sacrifice, is ceaselessly brought about among us and always arrives at the throne of Grace, at God’s presence.”17

Hence, Christ’s declaration over the cup as the “blood of the covenant,” is a bold and unmistakable assertion that, in his office of high priest of the New Covenant, in the celebration of the liturgy of that covenant in the Holy Eucharist, Christ himself “will reestablish the bond of kinship between God and man. In this way, ‘the words of Sinai are intensified to an overwhelming realism.’ The Last Supper was fundamentally the ‘sealing of the covenant,’ and the Eucharist is now ‘an ongoing reenactment of this covenant renewal.’”18

Hence it is clear that the inspired author of Hebrews illustrates the institution of the Holy Eucharist by Christ in the upper room as a new Yom Kippur (cf. Heb. 9:11-14, 24-26).19

With that in mind, when the baptized behold the Holy Eucharist, they are able to understand that it is, in fact, the true Jerusalem, for the celebration of the Holy sacrifice of the Mass is simultaneously heavenly and earthly, bringing to the world the “tent which is the Body of God, which as a risen Body always remains a Body and embraces humanity. And, at the same time, since it is a risen Body, it unites [man] with God.”20

Christ, the Eucharistic High Priest in the Order of Melchizedek

Thus, the inspired author of the Letter to the Hebrews evidently saw this connection between Christ and Melchizedek, and realized the depth of the implication of this typological connection. He saw Christ as a “new priest, who would offer a new sacrifice consisting of his own body, thus inaugurating a new covenant.”21

But when Christ came as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation), he entered once for all into the Holy Place, not with the blood of goats and calves, but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption. For if the blood of goats and bulls, with the sprinkling of the ashes of a heifer, sanctifies those who have been defiled so that their flesh is purified, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to worship the living God! For this reason he is the mediator of a new covenant, so that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, because a death has occurred that redeems them from the transgressions under the first covenant (Hebrews 9:11-15).

In considering the content of this article, this text poses a point of query, that query being, “at which point in Christ’s life did he most perform this all-encompassing function of high priest in the order of Melchizedek, wherein he offered a sacrifice, expiated sin, instituted a New Covenant and established himself as mediator of said covenant?” The most likely answer would be in his contemplation of the institution of the Holy Eucharist, as opposed to the Calvary event. This is mainly because it was at that moment that Christ pronounced the climactic words, “this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26:28). In that one act, Christ not only established a New Covenant, he effectively establishes himself as mediator of that covenant, and shows its superiority to the Mosaic Covenant, particularly in the juxtaposing wordplay “this is my blood of the covenant,” which, to any covenant-minded Jew would evoke the memory of Moses’s words, “behold the blood of the covenant” (Exodus 24:8). Thus, in additionally stating the words “shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins,” Christ was instituting himself as the fulfillment of the Jeremiah prophecy (cf. Jeremiah 31:31) which gave the prophetic assurance of the remission of sins, “for I will forgive their evildoing and remember their sin no more” (Jeremiah 31:34).

What is truly noteworthy, however, are Christ’s words, “my blood shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26:28). In this phrase, Christ asserts clearly that this New Covenant he was instituting brought the absolute guarantee of the expiation of sins for the covenanted, but it also brings to mind, at least for the Jews, Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, wherein the Levitical high priest would offer sacrifice for the atonement of the covenant relationship of the people and God. Hence, when the author writes, “He entered once for all into the sanctuary” (Hebrews 9:12), he is, again, presupposing that his readers will make this connection of the work of the Levitical high priest, who, “after immolating the victims entered into the invisibility of the earthly [Mosaic Covenant] sanctuary in order to carry out the expiation of sins by sprinkling the sacrificial blood and the death of Jesus… and his ascension into the invisibility of heaven [after his institution of the Holy Eucharist].”22

Hence, it is possible to affirm with certitude that the inspired author recognized Christ as the high priest of the New Covenant precisely in the events that took place in the upper room. In conclusion, examining the gifts of bread and wine offered during Christ’s last supper, and contrasting these with the gifts offered by the Old Testament priest-king, Melchizedek (cf. Genesis 14:18), would have inevitably led the inspired author of the Letter to the Hebrews to the realization that Christ “the new priest, by manifesting himself in the offering of his body at supper, was precisely—in fulfillment of the prophecy of Psalm 110:—the [high] priest [in the order of] Melchizedek.’”23

- Pope Benedict XVI. “HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI.” 3 June 2010: Solemnity of the Sacred Body and Blood of Christ | BENEDICT XVI. Accessed June 19, 2017. w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20100603_corpus-domini.html. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI. “HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI.” 3 June 2010: Solemnity of the Sacred Body and Blood of Christ | BENEDICT XVI. Accessed June 19, 2017. w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20100603_corpus-domini.html. ↩

- Hahn, Scott W. “The Eucharist as the Meal of Melchizedek.” 1996. Accessed June, 2017. ewtn.com/faith/teachings/euchc4.htm ↩

- Horton, Fred L. The Melchizedek Tradition: a Critical Examination of the Sources to the Fifth Century AD and in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Vol. 30. Cambridge University Press, 2005, 89. ↩

- O’Neill, Colman E. Summa Theologiae: Volume 50, The One Mediator: 3a. 16-26. Vol. 50. Cambridge University Press, 2006., 157. ↩

- O’Neill, Colman E. Summa Theologiae: Volume 50, The One Mediator: 3a. 16-26. Vol. 50. Cambridge University Press, 2006., 155. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Shameless Popery.” Early Church Fathers on the Eucharist (c. 200 – c. 300 A.D.) – Shameless Popery. Accessed June 19, 2017. shamelesspopery.com/early-church-fathers-on-the-eucharist-c-200-c-300-a-d/. ↩

- O’Neill, Colman E. Summa Theologiae: Volume 50, The One Mediator: 3a. 16-26. Vol. 50. Cambridge University Press, 2006., 157. ↩

- McMichael, Ralph N. Eucharist: A guide for the perplexed. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010, 72. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pacwa, Mitch, SJ. The Eucharist: a Bible study guide for Catholics. Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2013. ↩

- Binz, Stephen J. Eucharist. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications, 2005, 14. ↩

- Stone, Darwell. A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist. Vol. 2. Longmans, green, 1909, 76. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI. Meeting with the Parish Priests of the Diocese of Rome: Lectio divina (February 18, 2010) | BENEDICT XVI. Accessed June 14, 2017. w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2010/february/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20100218_parroci-roma.html. ↩

- Hahn, Scott W. “The Eucharist as the Meal of Melchizedek.” 1996. Accessed June 14, 2017. ewtn.com/faith/teachings/euchc4.htm. ↩

- Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal. Many Religions, One Covenant: Israel, the Church, and the World. Ignatius Press, 2015, 45. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI. Meeting with the Parish Priests of the Diocese of Rome: Lectio divina (February 18, 2010) | BENEDICT XVI. Accessed June 14, 2017. w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2010/february/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20100218_parroci-roma.html. ↩

- Abeynaike, Christopher Robert, O.Cist. “The Eucharist and the Letter to the Hebrews.” Sancrucensis. July 04, 2015. Accessed June 14, 2017. sancrucensis.wordpress.com/2015/07/04/the-eucharist-and-the-letter-to-the-hebrews/. ↩

- Abeynaike, Christopher Robert, O.Cist. “The Eucharist and the Letter to the Hebrews.” Sancrucensis. July 04, 2015. Accessed June 14, 2017. sancrucensis.wordpress.com/2015/07/04/the-eucharist-and-the-letter-to-the-hebrews/. ↩

- Abeynaike, Christopher Robert, O.Cist. “The Eucharist and the Letter to the Hebrews.” Sancrucensis. July 04, 2015. Accessed June 14, 2017. sancrucensis.wordpress.com/2015/07/04/the-eucharist-and-the-letter-to-the-hebrews/. ↩

This article is truly wonderful. The light of God shines through Marcus in this.