Question: There has been a great deal of talk recently about the fact that Christians cannot be rigid, and that rigidity compromises mercy and the Gospel. The Pharisees are used as examples of this. Why is there so much emphasis on this, and what can it mean?

Answer: In the 1980s, there was a move in many parts of the Church, especially in seminaries, to treat every attempt to emphasize orthodoxy by tagging it as someone being “rigid.” I recall that in the seminary where I taught, the rector put in a seminarian’s evaluation that he was “rigid.” He was asked by the rector at the time if he had any reaction, and he replied that the rector could use any other word except “rigid.” Today, some ecclesiastics use that word to characterize everyone from those who like the “extraordinary” form, to those who think there is actually a Catholic truth which is “absolute.” The word itself is not to be condemned, but as usual certain distinctions must be made.

The word “rigid” is perhaps an opposite of the word “tolerant.” Bishop Sheen once said that toleration was for people, but not for ideas; and, intolerance was for ideas, but not for people. This pretty much summarizes a balanced opinion towards the difficulties in our Church today. The distinction in this regard should be based on the proper conception of absolute truth. It is not rigidity to think that there are absolute truths, or that one objectively appreciates a certain style of liturgical celebration over other styles. Rather, rigidity occurs in one’s attempt to impose this on others, without any concern for the ability of the other to express their opinions and preferences.

Recently some Catholics in the political discourse of the United States have condemned systematic thought because it was responsible for extreme rigidity. If this were true, then logic, and the affirmation that there was an objective truth, would be the origin of a vicious intolerance towards the ideas of others. In fact, it is not true.

Therefore, one must make a distinction in the use of the term “rigid.” If the word “rigid” means that there can be no deviation in thought or practice in the Church on any subject, and is reflected also in a personal condemnation of the people who agree with this theory, then it should be tagged and criticized. In fact, there is much room in the Church for legitimate discussion and dialogue. Questions are not bad, but are often a search for the truth. As the present Pope has observed, people are very important.

But the very nature of the affirmation of the human race, and respect for other people, is based on their objective nature. Moreover, the truth about man—as John Paul II so prophetically observed in his first encyclical—must be objective and universal. In addition, this truth is seen in its most complete expression in the nature of Christ, and his redemption. The Creed and the Sacramental Order are part and parcel of this objective truth. Error concerning these matters has no rights, and if the truth is objective, then it cannot change by culture or epoch. Either Jesus is a divine person with two natures, or he is not. This does not depend on time or culture. To affirm that there is both a philosophia perennis, and a whole Catholic structure for ideas which must be affirmed if one is to call himself “Catholic,” this is not rigidity. It does not reject charity towards another, nor does it deny the fact of legitimate discussion of these truths within the parameters of the Creed and Sacred Tradition. There have been a number of schools of thought within those parameters which the Church has always encouraged.

Moreover, to apply the term “rigid” to logical, systematic truth is to deny the axiom of non-contradiction, which states that a thing cannot both be, and not be, the same thing, at the same time, in the same respect. One who makes truth dependent on sentiment, or situation, denies the very statement he affirms in stating so. If there are no absolute truths, that statement cannot be an absolute truth.

By the same token, the fact that one affirms that there is an absolute truth about the world which is logical, makes sense, and is systematic, means that regarding human beings, one must treat them, and their ideas, with respect.

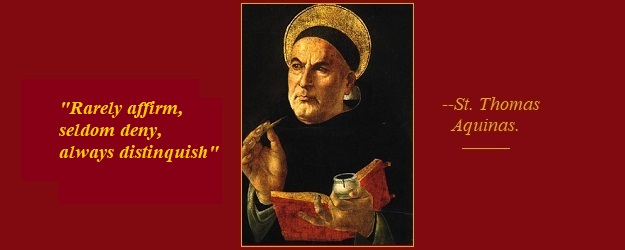

Thomism came in for some criticism in the public discourse. One forgets that the best summary of Thomism is: “Rarely affirm, seldom deny, and always distinguish.” What better expression could there be for people, and their ideas?

_________

Question: Can you give me some pointers on the nature of mysticism?

Answer: The nature of mysticism has been a subject of great misunderstanding in the Church. This is more because of the term, rather than the idea. It has come to be identified with extraordinary phenomena, like visions and trances. As a result, many priests had encouraged people to have nothing to do with mysticism.

In addition, the whole idea of the spiritual Church, which would encourage such experiences, seems to be inimical to the institutional Church, which in some people’s minds is threatened by too much emphasis on extraordinary knowledge and experiences. The practice smacks too much of the ancient heresy of “Gnosticism” which taught that there was special knowledge taught by the Holy Spirit which no one else could interpret or judge, including the hierarchy. The Charismatic Church was a threat to the institutional Church.

Vatican II redirected Catholics instead to the universal call to holiness, which is based on the experience of God, brought to each Christian in baptism, by sanctifying grace, and the character of the conformity of the Christian to Christ as priest, prophet, and king.

Traditional spiritual books express the progress in this holiness under the titles of the “ascetical” and “mystical” life. The ascetical life is the progress in prayer, which the Christian initiates through his works, and is characterized by the virtues. The mystical life is the natural continuance of that prayer when God assumes the process through the application of the sanctifying gifts of the Holy Spirit. The Church, therefore, teaches that the mystical life properly understood is not extraordinary, but rather the natural completion of grace.

There is an excellent book called Enthusiasm by Msgr. Ronald Knox which explains the proper understanding of mysticism. It is a history of the heretical “mystical” movements in the Church. Msgr. Knox was of the opinion that the Charismatic Church is necessary for the complete experience of the Church, a teaching shared by Vatican II. He also was very aware that there were great difficulties in any mystical movement which he called “enthusiasm.” He gives several paradoxes of mysticism which would help to guide mysticism properly understood.

What chiefly distinguishes the mystic’s prayer from the ordinary experiences of prayer is not that it is a fruit of grace, or that it is not meritorious, but that the mystic is aware of it. Though infused contemplation is a special experience of grace, our acceptance is not.

As the mystic becomes more aware of the presence of God, his concepts of God become less distinct. This is because the awareness is more based on love than on reason, and he knows God is infinite, but a mystic’s concepts are not. Knox says: “We do not just think about God, we think God.”

The inner nature of our experience of God in infused contemplation cannot be reduced to acts of reason, will, or affections within human control. This is because they are all transformed in God. One does delight in God, but this is very different from earthly delight.

The will becomes more and more the center of prayer, but our acts become less discernible. Again, this is because God is the primary actor. In contemplation, numerous acts become more one long sustained action of loving attention to God himself. This must have an effect in our everyday actions with our neighbor.

The more someone experiences the prayer of simplicity or infused contemplation, the less they ask for. This does not mean that there is no petitionary prayer, but rather that from the union of love, the soul is more content to let God decide what is best.

The more one enters into union with God, the less one becomes conscious of themselves. Humility and thanksgiving characterize a life of inner joy, even in the face of intense suffering and misunderstanding. The heresy of quietism bore a superficial resemblance to this simplicity, but held that all reflections or desires were infidelity to God. One can certainly reflect on the beauty of the relationship with God if the purpose is to thank him, and desire more union with the beloved. Some have actually held that it is selfish to desire one’s own salvation. God desires it, and so should we, by his grace. This is always other-centered. This awareness should NOT involve a conscious attempt to empty the mind of content, and the will of desires. This condition of simplicity is not our work, but his. God gave us a mind to think with, and a will to desire. If he gives us an experience of himself beyond a word encounter, this is his to do.

The person also becomes less conscious of living virtuously. This does not mean that one should not be assiduous in virtue, but one should be content with ordinary progress in the virtues of one’s state. Overly ascetical actions were always frowned upon by mystics like Teresa of Avila, who considered kindness, generosity, and cordiality as much more important than fasting and scourging.

It should be clear, then, that true mysticism is the result of an inner union with the Trinity, and adopting God’s point of view concerning inner transformation. It is proven through one’s ordinary virtues done with great love. At times, it may be accompanied by extraordinary phenomena because of the power of the experience, but this is not necessary, or even desirable. Finally, if the understanding and desires one has in such a state in any sense contradicts the Creed, or the teachings of the Church, then one cannot be experiencing the extraordinary presence of God.

It seems to me that the word rigid is not logical to name a Christian person It does not describe a Christian person or their Faith.. Saying the Nicene creed at mass is certainly not rigid. St Thomas Aquinas in theology and philosophy is quite logical not rigid. One shows mysticism when one concentrates and lives a spiritual life with the Holy Spirit and activates interest and love anytime for those in need and less fortunate such as found in the canonized blessed and Saints.

On judgement day a soul needs to be reconciled with God the Father.

If the person believes there is a right to abortion even in limited cases, and believes that marriage includes same sex couples, are they reconciled with the Father on their judgement day?