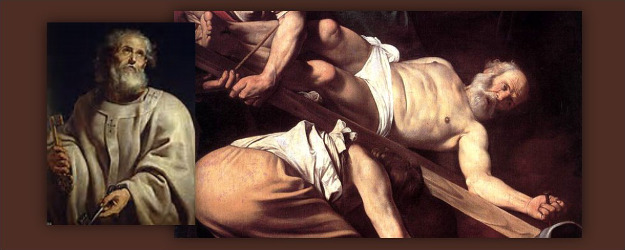

Crucifixion of St. Peter, by Caravaggio (1601); inset, St. Peter as Pope, by Peter Paul Rubens (1610-12).

Most Catholics seem to know, whether they accept it or not, what the job of the pope is. He sort of runs the Church from a central location; he is infallible (protected from error) in his serious public pronouncements on the subject of faith and morals; he is the administrative head of the Church, possessing immediate jurisdiction over every Catholic,1 a power used very rarely. Lastly, and this came to light during the peregrinatic papacy of John Paul II, he is the universal teacher of the Faith.

While this list may not be exhaustive, it comprises perhaps the most important, publicly known, attributes of the successor of St. Peter. But there is a certain one-sidedness to all these things. They are seen in a structural-functional way. One might be tempted to refer to them as legal descriptions of the papacy as an office. Consider, for example, the clearest expression of this view in the section on papal infallibility of Vatican I:

We . . . teach and explain that the dogma has been divinely revealed that the Roman Pontiff, when he speaks ex cathedra, that is, when carrying out the duty of the pastor and teacher of all Christians in accord with his supreme apostolic authority he explains a doctrine of faith or morals to be held by the universal Church, through the divine assistance promised him in blessed Peter, operates with that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer wished that His church be instructed in defining doctrine on faith and morals; and so such definitions of the Roman Pontiff from himself, but not from the consensus of the church, are unalterable. 2

Vatican I, in its Dogmatic Constitution I on the Church of Christ, refers, of course, to the scriptural foundation of papal authority, teaching and jurisdiction. Our Lord asked the Father for apostles and those who would believe their word. 3 He then sent the apostles out as he had been sent by the Father, 4 and wished that these “pastors and doctors” 5 would continue until the end of the world. 6

He placed Peter the apostle, calling him Cephas, 7 “rock,” reiterating this talk and new name at Caesarea Philippi after Peter’s confession that Jesus was “the Christ, the Son of the living God.” 8 Jesus also commissioned Peter to care for the Church, telling him to “Feed my lambs . . . . Feed my sheep.” 9 But the earliest non-scriptural reference used by this cardinal document is Irenaeus’ Adversus haereses 1, 3. c3, and the next earliest is from Ambrose’s (A. D. 340-397) Ep 11. 4, written in A. D. 381. The quote from Irenaeus relates to the proof of the early apostolic succession. 10 The section from St. Ambrose, who was no stranger to struggles with the Emperors, is a letter to the three Emperors ruling at the time urging them to support Pope Damasus, the duly elected pope, against the Arian papal claimant, Ursinus. 11 Time and again, the popes have had to clarify the relationship of the Church with the secular (nevertheless Christian) rulers and this gave rise to the seminal document clarifying these relationships. In a letter to the Emperor Anastasius in 494 AD, Pope St. Gelasius I writes: “Two there are, august emperor, by which this world is chiefly ruled, the sacred authority of the priesthood and the royal power. Of these the responsibility of the priests is more weighty in so far as they will answer for the kings of men themselves at the divine judgment.” Gelasius goes on to say that although the emperor is the highest in earthly dignity, he should piously submit to the priesthood in Church matters. 12 In his decree, On the Bond of Anathema, Gelasius clearly delineates the theology of church and state by saying that essentially the bishops and the emperors operate in separate spheres, and in each sphere, their authority is absolute. In the past, he says, rulers were also the high priests, “pontiffs,” but Christ himself, who was true king and true priest, changed this relationship, so that now there are separate spheres of jurisdiction. 13

But there is a forgotten aspect of the calling to the papacy that has been obscured because of the constant need to clarify papal authority. Neglected have been:

- The appreciation of the pope as a bishop and the meaning of what it is to be a bishop;

- The obscuring effect of notoriously immoral and/or power-hungry popes; 14

- The ultimate meaning of Peter’s calling.

Firstly, what is the role of a bishop in general. The Church, as can be clearly seen in the following quotations, expects the bishop to be a mirror of Christ in every way. The Catechism of the Catholic Church points out that the bishops sanctify the church by their ministry of Word and sacrament, but also by their word and example, “not as domineering over those in {their} charge but being examples to the flock.” 15 So, above all, the bishop, any bishop, should be a shining example of Christian life in every respect. They should exercise their authority “so as to edify, in the spirit of service which is that of their Master.” 16 St. Clement of Rome in his “Letter to the Corinthians,” gives us an eyewitness view of the way the first bishops acted. After showing how Christ sent the apostles out as bishops, who with full knowledge appointed other bishops and deacons, “testing them by the Spirit,” Clement states: “Our apostles knew through our Lord Jesus Christ that there would be strife for the office of bishop . . . .” 17

Clement says that these bishops and deacons have ministered to the flock of Christ “without blame, humbly, peaceably and with dignity . . . .” 18 Instead of lording it over the Corinthians, who were “in revolt against the presbyters,” 19 and by extension against the bishops. Clement demonstrates his spiritual unity with the even the rebels: “Do we not have one God, one Christ, and one Spirit poured out upon us? And is there not one calling in Christ?” 20 He says that the reports of this rebellion are coming to him from Christians and non-Christians alike, and by heaping blasphemies on the name of the Lord, you (the rebels) “ will create a danger to yourselves.” 21 So Clement is concerned not first with Church discipline for the sake of the Body, but one gets the clear impression that Pope St. Clement of Rome has as his primary concern the souls of those in revolt. This explains the next section of his letter, which reminds the Corinthians of love. Reflecting the teaching of St. Paul, 22 Clement writes:

Love covers a multitude of sins. Love endures all things, is long-suffering in everything. There is nothing vulgar in love, nothing haughty. Love makes no schism; love does not quarrel; love does everything in unity. In love were all the elect of God perfected; without love, nothing is pleasing to God. In love did the Master take hold of us. For the sake of love which he had for us did Jesus Christ our Lord, by the will of God, give his blood for us, his flesh for our own flesh, and his life for our lives. 23

St. Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, speaks about the requirement that the faithful submit to the bishops: “Indeed, when you submit to the bishop as you would to Jesus Christ, who died for us … 24 And, “Let everyone respect the deacons as they would respect Jesus Christ, and . . . respect the bishop as a type of the Father …” 25

Ignatius used the same sentiments in his Letter to the Smyrnaens: “You must follow the bishop as Jesus Christ follows the Father …” 26

A telling remark of St. Polycarp is recounted by St. Irenaeus: “He had always taught those things which he had learned from the Apostles, and which the Church had handed down, and which are true. To these things all the Churches in Asia bear witness, as do all the successors of Polycarp even to the present time . . . . Once he was met by Marcion, who said to him: ‘Do you recognize me?’ and Polycarp replied, “I recognize you as the firstborn of Satan!’” 27

Here Irenaeus shows other Christ-like qualities which should be possessed by bishops, and again, by extension, by the bishop of Rome. Firstly, they should hold tightly, not merely to the Apostolic succession, but with it, to the truth which comes from the Apostles. 28 The above quotation shows that to be a bishop is less an honor (after all, a bishop is chosen by God, and has nothing to do with the man), but a sacred trust and constant burden. The task of the bishop is to teach all comers this deposit of Faith—the faithful, heretics, sinners, and non-believers, even to the point of martyrdom, as Sts. Polycarp and Ignatius demonstrated.

Pope St. Siricius in his letter to Bishop Himerius of February 10, 385 takes the idea of the sacrificial guardianship of the Faith up strongly:

And since it is necessary for us to succeed to the labors and responsibilities of him whom, through the grace of God, we succeeded in honor … For in view of our office there is no freedom for us, on whom a zeal for the Christian religion is incumbent greater than all others, to dissimulate or be silent. We bear the burdens of all who are oppressed, or rather the blessed apostle Peter, who in all things protects and preserves us, the heirs, as we trust, of his administration, bears them in us.” 29

St. Ambrose, writing with other members of a synod to Pope St. Siricius, verifies that the office of the pope requires Christ-like behavior:

We recognize in the letter of your holiness the vigilance of the Good Shepherd. You faithfully watch over the gate entrusted to you, and with pious solicitude, you guard Christ’s sheepfold, you that are worthy to have the Lord’s sheep hear and follow you. Since you know the sheep of Christ you will easily catch the wolves, and confront them like a wily shepherd, lest they disperse the Lord’s flock by their constant lack of faith, and their bestial howling. 30

The second point, that the ultimate meaning of the papacy is obscured because of the lives of Popes which were less than honorable, leads and has led for centuries, Catholics to fall back on the doctrinal point of authority, primacy and infallibility. The morals of the popes have no effect on their authority. But popes are not impeccable. A fascinating incident in the early Church will highlight this lesson. 31

Briefly, in the period beginning in 535, the Church was plagued by the Monophysite heresy, and heavy with the interference of the emperor Justinian and his devious wife, Theodora, all of which spilled over into papal intrigue. Theodora promised the heretical deacon, Virgilius, who would do anything to become pope, seven hundred pounds of gold, if, when General Belasarius sacked Rome and put him, Virgilius on the papal throne (becoming anti-pope), replacing the real, courageous and now dead, Pope Agapitas (535-6), he would abrogate the Council of Calcedon and approve Monophysitism. Virgilius agreed, and was put on the throne on March 29, 537. But in June, 536, St. Silverius had been elected the real pope. General Belasarius exiled Silverius who subsequently starved to death. At Silverius’ death, Virgilius became the real pope, and was reluctantly proclaimed by the clergy of Rome, as the only one, even though a murderer, who would not be killed upon accession to the Throne of Peter. Warren Carroll evaluates the situation at the time:

In all the history of the See of Peter there is no darker moment than this, the Year of Our Lord, 539, with Rome in the bonds of Theodora’s minions while she waited in Constantinople of the remainder of the promise of “our most dear Virgilius.”

When nothing happened, Theodora wrote to Virgilius asking him to fulfill his part of the bargain. Virgilius, now the true pope, responded: “Far be it from me Lady Augusta; formerly I spoke wrongly and foolishly, but now I assuredly refuse to restore a man who is a heretic and under anathema {the heretical, deposed Patriarch, Anthimus}. Though unworthy, I am vicar of the Blessed Peter the Apostle, as were my predecessors, the most holy Agapitus and Silverius, who condemned him.” 32

This story, which should inspire awe and wonder in all readers, shows not only the protection against errors in the Faith guaranteed by God to legitimate popes, but the courage of this former sleazy anti-pope. It is also an opening to the third principle—a failure to consider the ultimate meaning of the call to the Chair of Peter. The Catechism makes the point well when it states that ecclesiastical service calls for ecclesiastics to act in persona Christi capitum. 33 The Catechism further explains: “Finally, it belongs to the sacramental nature of ecclesial ministry that it have a personal character. Although Christ’s ministers act in community with one another, they also act in a personal way. Each one is called personally: ‘You, follow me’ (Jn 21:22; Mt 4:19-21; Jn 1:4) in order to be a personal witness within the common mission, to bear personally responsibility before him who gives the mission, acting ‘in his person’ for other persons … 34 The Catechism quotes Lumen gentium of Vatican II regarding bishops in general: “The bishops as Vicars and legates of Christ govern the particular churches assigned to them by their councils, exhortations, and example … ” in addition to their authority and power, “which indeed they ought to exercise so as to edify in the spirit of service which is that of their master.” 35

The main point throughout the latter part of this paper has been that the Church continually exhorts all those in ecclesiastical service that they must be servants as Jesus was, and told us to be. It also used the model of the Good Shepherd time again. The Catechism states: “The Good Shepherd ought to be the model and ‘form’ of the bishop’s pastoral office.” 36 The roles of servant and shepherd are closely related. One could say that the job of a shepherd is to serve the sheep, since they do not know where the best pastures are. The shepherd leads them there, and at night, rounds them up and corrals them for their protection. 37 He scares off predators. He searches for lost ones. 38 But perhaps the most telling role of the shepherd-servant becomes apparent when Our Lord says: “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep … ” 39 St. Matthew records: “And Jesus said to them, ‘You will all fall away; for it is written, “I will strike the shepherd and the sheep will be scattered.”’ 40 So the test of an ecclesiastic good shepherd is really, not just his willingness to suffer and die for the sheep (because “talk is cheap”), but the actually suffering of martyrdom, either of blood or spirit. 41

In the movie, “Shoes of the Fisherman,” the Cardinal-Prefect of the congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith tells the newly elected pope who is facing a very difficult decision, that this is the moment of solitude which all popes reach: “I have to tell you there is no remedy for it. You are here until you die, and the longer you live, the lonelier you will become … Like it or not, you are condemned to a solitary pilgrimage from the day of your election until the day of your death. This is a Calvary, Holiness, and you have just begun to climb!” 42

Lastly, Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, in discussing the essence of the papacy brings up a writing of the famous Cardinal Reginald Pole, De summo pontifice(1569). The Cardinal wrote, referring to Isaiah 9: 6:

When you see that Christ is born for us as a child, and sent to us, with regard to his vicar relate this to his election. It is to a certain extent his birth. That means that you must think of him that he is not to such an extent born for himself, that he has been elected for himself, but for us, that is for the entire flock … In the office of shepherd he must regard himself and behave as the least, and acknowledge that he knows nothing other than this alone, that he has been taught by God the Father through Christ …

Then, Cardinal Pole refers to the next verse, “… and the government will be upon his shoulder.” This, according to Pole, refers to the onerous burden Christ bears for us. It is a more than human burden on human shoulders for Christ’s vicar: “The strength in which the vicar of Christ must become like his Lord is the strength of the love that is ready for martyrdom.” 43

In conclusion it can be said that through the fog of the defense of papal authority, the true calling of each pope comes out by reading between the lines. The Liber Pontificalis tells us that of the first 30 popes, 21 were martyrs. 44 As Pope St. Gregory the Great wrote: “the proof of love, therefore, is the demonstrability of works.” 45 As a final example to all popes, The Martyrdom of St. Polycarp says that he “was outstanding, whose martyrdom all desire to imitate, because it was so much in accord with the Gospel of Christ.” 46 Of all Christians, the pope above all, is called to suffer as did the One whose vicar he is.

This brings us to a present day application. The popes of recent years have had to endure a martyrdom from both sides in the Church (some of whom are not really “in” the Church). This is a bit surprising since one side claims to be defending papal authority and orthodoxy in doctrine. These Catholics, wishing that the popes of recent decades would “crack down,” have missed the significance of the ultimate vocation of the papacy.

In a very perceptive study on the pope as the “rock,” Father Stanley Jaki, O.S.B., states: “What is worse, the evangelical patience of two popes, John XXIII and Paul VI, was taken all to often for a weakness which had no choice but to tolerate even rank disloyalty.” 47 Nevertheless, what was seen by some as weakness, was heroic endurance and is part of the papal calling:

The function reserved for a human called and declared to be rock will appear truly biblical and, therefore, superhuman only by recalling that before Simon was called, and constituted rock by the Son of God, only God was called Rock in the written word of God … The more the papacy reveals its endurance, the more it becomes clear that the core of that endurance is not the endurance of power, but the patience to endure any power … 48

- Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma, tr. by Roy J. Deferrari (Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire: Loreto Publications, 1954), 1827, 1829. All subsequent references to this work will be indicated by a D. ↩

- D., 1839. ↩

- Jn 17: 20ff RSV ↩

- Jn 20: 21 RSV ↩

- D., 1821. ↩

- Mt 28:20 RSV ↩

- Jn 1: 42 RSV ↩

- Mt 16: 13-16 RSV ↩

- Jn 21:15 RSV ↩

- St. Eusibius, Adversus haereses, 1:3, chap 3 in ↩

- Ambrose of Milan, Letter XI A. D. 381 in http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/ambrose_letters_02_letters11_20.htm accessed 11/25/05. ↩

- Pope St. Gelasius I, Letter to the Emperor Anastasius, in The Crisis of Church and State: 1050-1300, ed by Brian Tierney (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1980), 13-14. ↩

- Pope St. Gelasius I, On the Bond of Anathema, in ibid., 14-15. Eric Voegelin insists that this constant attempt of the Emperors to control the Church is a remnant of Gnosticism still infecting the Roman rulers from pagan times. The rulers, according to Voegelin, never really sorted out what their conversion meant, hence the struggles with the pope and bishops. See, Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952), chaps., 3 and 4. ↩

- Today it seems that even Catholics, when speaking about the pope, need to point out that there have been some bad popes. It’s like an obsession. ↩

- The Catechism of the Catholic Church 2nd ed., (New York: Doubleday, 1997), 893, quoting 1 Peter 5:3. All subsequent references to the Catechism will be designated by Cat. ↩

- Cat., 893. ↩

- Clement of Rome, Letter to the Corinthians, 44: 1 in William A. Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, vol. 1 (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1970), 10. All subsequent references to Jurgens, The Faith of the Early Fathers, will be Jurgens. ↩

- Ibid., 44: 3. ↩

- Ibid., 47: 6. ↩

- Ibid., 46: 6. This author’s emphasis. ↩

- Ibid., 47: 7. ↩

- 1 Cor 13:1 NIV ↩

- Clement, Letter 49:4-6, in Jurgens, 11. ↩

- Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Trallians, 2:1, in Jurgens, 20. ↩

- Ibid., 3:1in Jurgens, 20. ↩

- 8:1, in Jurgens, 25. ↩

- Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, 3: 3, 4, in Jurgens, 90. ↩

- See, also, ibid., 4: 33, 8 in Jurgens., 97. ↩

- Pope Siricius, Letter of Pope Siricius to Bishop Himerius of Tarragona, 385 AD, in Pierre Coustant, ed. Epistolae Romanum pontificum (Paris: 1721; reprint Farnborough, 1967), 623-638; available from http://faculty.cua.edu/pennington/Canon%20Law/Decretals/Siricius, accessed 11/4/05. ↩

- Synodal Letter of Ambrose, et al., to Pope Siricius, ca. A.D. 389: 42, 1, in Jurgens 148, 1252a. ↩

- The following story is from Warren Carroll, A History of Christendom, vol. 2, The Building of Christendom (Front Royal, Virginia: Christendom Press, 1987), 167-173. ↩

- Letter of Pope Virgilius to Empress Theodora 538 or 539 AD, in Carroll, 161. ↩

- Cat., 875. ↩

- Cat., 878. ↩

- Cat., 894, quoting Vatican II, Lumen gentium, 427. See, also, Luke 21: 25-27: “And he said to them, ‘The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them; and those in authority over them are called benefactors. But not so with you; rather let the greatest among you become as the youngest, and the leader as one who serves. For which is greater, one who sits at table, or one who serves? Is it not the one who sits at table? But I am among you as one who serves.” ↩

- Cat., 896. ↩

- The shepherd does not do this to be mean, as some renegades constantly imply. ↩

- See, Jn 10: 11-15; Mt 18: 12; and Mt 15: 24 NIV. ↩

- Jn 10: 11-15 NIV. ↩

- Mt 14: 17 NIV. ↩

- Psalm 22, pointing to the “dry” martyrdom of Christ says: “All who see me mock at me, They make mouths at me and wag their heads; ‘He committed his cause to the Lord; let him deliver him, Let him rescue him, for he delights In him’” NIV. ↩

- Shoes of the Fisherman, 162 minutes (Hollywood: MGM Pictures, 1968), author’s emphasis. ↩

- Cardinal Reginald Pole, De summo pontifice in Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Church, Ecumenism and Politics: New Essays in Ecclesiology (Slough, England: St. Paul Publications, 1988), 40-1. ↩

- The Books of Pontiffs (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of the First Ninety Roman Bishops to A.D. 715, tr. by Raymond Davis (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1989. ↩

- Gregory the Great, Homilies on the Gospels 2: 30, 1 in Jurgens, vol. 2, 324. ↩

- The Martyrdom of St. Polycarp 19: 1, in Jurgens, 31. ↩

- Stanley L. Jaki, And On This Rock: the Witness of One Land and Two Covenants (Front Royal, Virginia: Christendom Press, 1997), 48. ↩

- Ibid., 49, this author’s emphasis. ↩

[…] on the theology of the papacy and the calling popes have to […]