Genesis 44 and 45 has it all: a foreshadowing of the atonement, forgiveness, providence, and a model for how to deal with suffering. This mini-gospel from the first book of the Bible anticipating the Gospel of Christ is a roadmap detailing the rubrics for a life of faith. Most importantly, it offers a message of hope for us today in the difficult times in which we find ourselves.

What follows offers mostly a theological reading of these two chapters in Genesis, though all four senses of Scripture (CCC, 115–119) can be gleaned in these powerful chapters. Our chapters are found in a section that serves as a bridge between the story of the Patriarchs and the Exodus, what scholars dub the Joseph Novella (Gen 37–50), a story some scholars surmise might have even been composed in Egypt or at least written for a Jewish diaspora community there1 and later affixed to the end of Genesis. Here we find the story of Joseph and his encounter with his brothers. Genesis 44 commences in Egypt after the youngest son of the Patriarch Jacob had risen to power in Pharaoh’s kingdom. Joseph found himself in the land after his brothers sold him into slavery years earlier because they could not tolerate his young, inflated sense of self. He was undoubtedly most grievously wronged by his siblings. Joseph had risen to a position of prominence, serving as viceroy to the pharaoh, and his brothers now came to Egypt for help during a drought, something ancient Near Eastern evidence confirms occurred often in the era, namely the migration of semitic people to and from Egypt during times of drought in the Late Bronze Age.

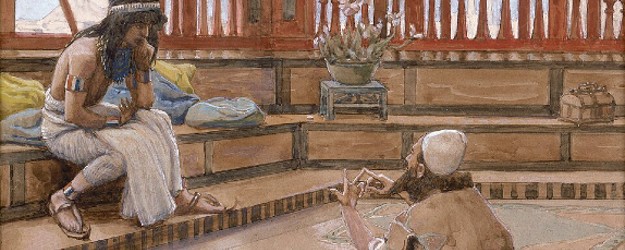

After some intrigue and trickery, it is made known to the brothers that their fate now resides in the hands of their aggrieved brother that they sold into slavery. They are summoned before Joseph to account for his cup that had been planted in Benjamin’s bag by Joseph’s command. Thus, the brothers are now in grave danger and are rightly terrified. They are at the mercy of the one they had wronged. Time for revenge, one might think. Joseph proceeds to reveal himself to his brothers. He shockingly offers them what we should understand as hesed in Hebrew, that is “grace, favor or loving kindness” by way of forgiving them. This alone demonstrates the Gospel, also revealing how we are to act today, making the story relevant for our time. In a tongue-in-cheek manner that anticipates the Church’s articulation of the seven deadly sins, Joseph tells his brothers as they depart to go back and collect their dad not to quarrel along the way (45:24). His time in Egypt, interestingly a region in antiquity that also produced wisdom literature similar to that of the Hebrew Bible, seems to have provided him wisdom into understanding just how corrosive to life the negativity of quarreling and strife can be.2 But there is even more to unpack in this story, revealing just how deep Sacred Scripture is.

Four salient elements come to the fore in these chapters. Firstly, Genesis 44:33 contains a remarkable foreshadowing of the future work of Jesus. When it appears to the brothers as though they are going to suffer because it seems Benjamin has been caught with Joseph’s cup, Judah tells Joseph, “Now therefore, please let your servant remain as a slave to my lord in place of the boy; and let the boy go back with his brothers.” In an amazing act of pure unselfishness, Judah presents himself as a sacrificial offering. He willingly offers his life for Benjamin’s, as he knows how the loss of his youngest son would impact his father, the Patriarch Jacob. It is hard not to see how this resonates with the later work of Jesus and his sacrificial offer of himself to his father. Judah’s desire to offer himself as a substitute for Benjamin is also remarkably a foreshadowing, seeing that Jesus later comes from the tribe of Judah, via the lineage of King David. Substitutionary atonement is foreshadowed in our story, for just as Judah desires to stand in the place for another, so Jesus does for humanity. Moses later interestingly also offers to do the same for Israel after their apostasy in the Golden Calf incident at Sinai recounted in Exodus 32. He freely offers his life instead of the people’s for their sin (Exod 32:32); thus, he too foreshadows the coming work of Christ.3

This story also hints at a unique bond between Judah and Benjamin, one that might be reflective of the later history of ancient Palestine and the perspective of the authors of the story.4 The two tribes that descend from these figures will later constitute the Southern kingdom of Judah and its successor, the Persian province of Yehud, the region that later provided posterity with the Hebrew Scriptures. The other brothers are indicative of the ten Northern tribes of Israel that was later conquered and exiled by the Assyrians in 721 B.C. Its former territory later became part of the Persian province of Samerina.5 This is all to suggest the text likely also demonstrates an ideological struggle during the time of its writing and editing, accounting for the emphasis on the sins of the brothers in their selling Joseph into slavery and the corresponding elevation of Judah. Yehud seems to have been where most of the writing and editing of the Hebrew Bible occurred; thus, Judah and Benjamin have their respective eponymous ancestors painted positively, whereas the other brothers who represent the northern tribes are portrayed as acting without much generosity. The final form of our story thus likely leaves traces of the later tension between Yehud and Samerina, much as scholars have noticed the struggles between Saul and David likely do as well.6

Secondly, that Joseph demonstrates a supreme act of forgiveness or hesed toward the immense wrong and harm that had previously been done to him by his brothers (see Gen 37) is remarkable and provides a model for us to emulate. We read of Joseph’s grace: “Then he threw his arms around his brother Benjamin and wept, and Benjamin embraced him, weeping. And he kissed all his brothers and wept over them. Afterward his brothers talked with him” (Gen 45:14–15). Joseph forgoes all punishment and need for retribution, demonstrating great hesed. Though his brothers merited punishment for their horrendous crime, he shockingly shows them love; God also uses the incident for the redemption of many, as Joseph will save the family and bring them to Egypt during this time of famine. In saving his family he saves the people of Israel. This also hints at the Paschal Mystery. In Genesis 45:21–22 he gives them provisions and even new clothes they certainly did not merit, thus demonstrating care and love.7 The message of forgiveness in this story undoubtedly coheres with the later words of Jesus.

Recall Jesus’ words that one must forgive seventy times seven times (Matthew 18:22), a code for always. It is interesting that Jesus uses the numeral seven here, as it was a Hebrew number signifying wholeness or completeness, as in the seven days of creation, thus suggesting the importance of forgiving for one’s wholeness and health! In the same Gospel, Matthew 16:14–15 reads: “For if you forgive other people when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive others their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins.”

It is rather difficult to square Jesus’ words here with the misguided Protestant notion of faith alone, especially when Scripture explicitly says salvation is not by faith alone (James 2:24).

Thus, grace (hesed) is shown forth in Joseph’s response in which he utterly forgives the wrong done to him and returns it with love, a model for us today as Jesus also later displays.

Thirdly, a much-needed reframing of reality for our time is on display in our story. Namely, the salient point and perspective that God’s providence ultimately reigns supreme. This becomes evident for Joseph when he articulates an understanding of why he had to undergo suffering at the hands of his brothers. Joseph comments in Gen 45:5, “God sent me before you to preserve life.” This calls to mind St. Augustine’s view that God permits evil so that a greater good may come. Joseph was sold into slavery and suffered greatly in being torn away from everyone and everything he knew and loved, but it all served a greater good. Joseph thus seems to have an epiphany uncovering the answer to his great suffering, something not all of us get in this life. Interestingly, “preserving life” in our passage can be translated as “to save life,” also calling to mind the work of Jesus again. Significantly, Jesus’ Aramaic name, Yeshua, derives from the verb “to save.” Hence, some translations of Genesis 45:5 read, “And now, do not be distressed and do not be angry with yourselves for selling me here, because it was to save lives that God sent me ahead of you.” God’s providence and directing of the affairs of human beings is undoubtedly on display here.

Genesis 45:7 then reads, “But God sent me ahead of you to preserve for you a remnant on earth and to save your lives by a great deliverance.” Earlier we noted Judah foreshadowed the atonement, but here Joseph seems to instantiate the same, making both Joseph and Judah redemptive figures prefiguring Christ. Note it is God here who does the sending. Humans only think their machinations make them the true arbitrators of all things. Joseph therefore realizes that God is the orchestrater of life, realizing ultimately God’s purposes prevail, not humans. Proverbs 19:21 reads: “Many are the plans in a person’s heart, but it is the Lord’s purpose that prevails.” This important theme continues as we read in Genesis 45:8: “So then, it was not you who sent me here, but God. He made me father to Pharaoh, lord of his entire household and ruler of all Egypt. It was God working through humans, even their evil actions.” These are profound and timely words for all of us today. Recall the words of Paul in Romans 8:28 when he writes, “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose.”

Fourthly, the final insight relevant for us today is bound up with the previous one. It is more intimated than explicitly stated but nonetheless present. Namely, the story demonstrates how one is to deal, or the posture one is to take, with pain and sorrow in this life, an inevitability for everyone.8 In spite of what Joseph had undergone, the text does not reveal even the slightest hint that Joseph gave in to bitterness or anger and that such emotions consequently impacted his judgment or behavior. It appears he did not let the inevitable and quite natural pain and grief due to his predicament cloud his actions in the least. In fact, the son of the Patriarch Jacob only returned injustice and suffering with kindness; he is thus a model for us all.

Joseph furthermore appears to have been diligent in his work, otherwise he would not have risen to rule Egypt as he did. Presumably, he was patient and kept the faith in spite of what must have appeared to be not just a disappointment, but a lost life for him. He exhibited steadfast patience even in the midst of suffering, for his suffering served a greater purpose and one day would give way to something better. He accepted his situation.9 No doubt, God’s ways are not our ways, nor is God’s timing aligned with the timing we desire of things (cf. Isa 55:8–9). It appears Joseph learned this and likely demonstrated his understanding of it by evidencing a spirit of waiting on God. As opposed to our cultural era’s natural inclination for instant results, God appears to be in it for the long haul, suggested by Joseph’s stay in Egypt away from his loved ones (see Robert Barron, The Great Story of Israel: Election, Freedom, Holiness; Word on Fire: Park Ridge, 2022, 37–38). Naturally, our finite minds have a difficult time grasping what God is up to, but usually we glimpse later in life why certain things turned out the way they did. However, if we do not in this life, the hope of the Christian faith is that in the next life we will see precisely how God’s providence was at work for us in this life.10

Thus, the interaction between Joseph and his brothers serves as a prefiguration of the Gospel of Christ and simultaneously brings to the fore how to live a life of faith today that will bring wholeness and peace. Hesed was on display through and through in our story. It is no coincidence that it also points to the later atonement of Christ through the eponymous ancestor of the tribe Jesus comes from, Judah. This is a harbinger, as King David descends from Judah and Jesus from David.11 Interestingly, our text likely also arises out of the tribe’s former region, the Persian province of Yehud as aforementioned above. It appears to be by God’s providence that we have a story from Genesis alluding to the atonement in a figure Christ descends from that also contains a rubric revealing how one is to live a life of faith. Namely, through forgiveness, trusting in God’s providence, and faithful perseverance in suffering. This story calls for a faith that fights the natural urge of giving into bitterness, despair, and anger.12 We are called to work on not letting adversities get the better of us, as Joseph so clearly mastered and demonstrated. Joseph told his brothers not to quarrel with one another (45:24), as he knew precisely how insidious anger and associated negativity such as despair can be, as if it is allowed to run amuck it has the potential to destroy everything in one’s life, even one’s health.

Patience and faith in God’s providence is what Joseph demonstrated. We must do the same and also be in it for the long haul, for we too can weather the storms and have assurance of something better to come. Judah’s sacrificial offering in our story also suggests that true life is about dying to self,13 as 1 Corinthians 10:24 reminds us, “Do not seek your own advantage, but that of the other.” Judah demonstrates how one is to sacrifice for others. Both Judah and Joseph reveal an amazing mini-gospel of love in this story.

Our story encapsulates so very much: sacrifice for others, forgiveness, trust in God’s providence, the posture to take when confounded by the adversities of inevitable suffering and pain that rise in this life as well as a profound foreshadowing of the Atonement. Judah here is clearly a prefiguration of Christ, especially when one takes into account that David and then Jesus came from his lineage and both are referred to as the anointed one of God.14 Joseph showed trust in God’s providence, even in the midst of tremendous suffering and he ultimately and profoundly returned hesed when he was given harm. Judah offered himself as a substitute for another; both brothers are thus paradigmatic models for us today. These timeless messages from this min-gospel all cohere well with the Gospel of Christ that is later revealed in the figure of Jesus the Christ.

- For the view that the Joseph story was composed in the Persian province of Yehud to address a Jewish diaspora community living in Egypt for purposes of inclusion into the larger Yahwistic community to some degree, see Diana Edelman, “Genesis: A Composition for Construing a Homeland of the Imagination for Elite Scribal Circles or for Educating the Illiterate?” In Writing the Bible: Scribes, Scribalism and Script (eds. Phillip Davis and Thomas Romer; London: Routledge, 2016), 47–66. For multiple instances suggesting the intimate knowledge of Egyptian culture on the part of the author(s) of the Joseph Novella, see Shirley Ben-Dor Evian, “Was the Joseph Story Written in Egypt During the Persian Period?” at TheTorah.com at: https://www.thetorah.com/article/was-the-joseph-story-written-in-egypt-during-the-persian-period and see Donald B. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph (Genesis 37- 50) (Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 20; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1970). ↩

- This naturally coheres with later Israelite wisdom literature when one reads in Eccl 7:9: “Anger resides in the bosom of fools.” ↩

- Additionally, in terms of foreshadowing Christ, one should recall Moses’s words in Deut 18:15: “The Lord your God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among your own people; you shall heed such a prophet.” For a treatment on how it takes a plethora of motifs, images, and pattering off of giant, paradigmatic Hebrew figures such as that of Elijah and Moses to begin to express who this first-century rabbi that traversed Palestine with a message of redemption and love truly was, namely God incarnate, see James S. Anderson, Extolling Yeshua (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2019). ↩

- One should also recall that Judah is the brother that suggested to his siblings they sell Joseph instead of killing him, thus saving his life (Gen 37:26–27). ↩

- The Assyrians repopulated the former kingdom of Israel after 721 BC with a variety of people groups, a common practice for this Empire. The Persian province of Samerina was later therefore a mixture of different people groups, which is implied even later in the New Testament in how the later Samaritans are portrayed. The present-day Samaritans on Mount Gerizim in the West Bank trace their lineage back to the former kingdom of Israel. ↩

- See Diana Edelman, “Gibeon and the Gibeonites Revisited” in Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period (eds. O. Lipschits and J. Blenkinsopp; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2003), 153–167 and Yairah Amit, “The Saul polemic in the Persian period,” in Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period, eds, O. Lipschits and M. Oeming (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006), 647–661. ↩

- No doubt this was at the prompting of Pharaoh (Gen 45:17–18). Sometimes it takes God working through others to move us, even by people not of our of faith tradition. Recall it is by God’s working through the Persian king Cyrus that the Israelites are allowed to return home from exile and to rebuild their temple. This can be seen in the prophetic book of Isaiah, specifically what scholars term Second Isaiah and Ezra 1:1–8. Here in Ezra one explicitly reads, “the Lord inspired King Cyrus of Persia . . .” In Second Isaiah, Cyrus is actually referenced as the messiah (Isa 45:1), which in Hebrew literally means the “anointed one.” He was anointed by God in this instance to let the Jewish people return from exile and go back home, and rebuild their temple in Jerusalem to God. Thus God was enacting his purpose through non-Jews demonstrating his providence over all humanity and creation, not just an elect group. ↩

- For an excellent treatment on suffering that explains redemptive suffering, see Pope John Paul II’s 1984 apostolic letter Salvifici Doloris. ↩

- That acceptance is so vital for wellbeing, an entire counseling theory has arisen around it entitled Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. ↩

- This calls to mind 1 Corinthians 13:12: “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” ↩

- It is interesting that one of the main messages of the book of Ruth is that David has Moabite blood, contravening the ethnocentric ethos of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Ruth, after all, is a Moabite. This point hints at Jesus being for all humanity, not just a select few. This coheres with Galatians 3:28 when one reads, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave of free, there is no longer male or female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” ↩

- This is not to deny that anger is natural and unavoidable because of sin in the world and our woundedness. It becomes a matter of what one does with anger. Anger serves as an alarm that something needs to be attended to in one’s life. ↩

- Pope John Paul II reminds us that a true life, ironically, consists of giving itself away. ↩

- “Anointed one” actually translates as “the messiah” in Hebrew and both David and Jesus historically took on this important title. Not only are they both designated by this term but it is presupposed in the Bible and later tradition that both are born in Bethlehem, which in Hebrew literally means “house of bread.” This obviously has huge significance in terms of Jesus and the Eucharist. ↩

Recent Comments