Nearly everyone reading this has probably heard something on the subject of vocational discernment. For those accustomed to Catholic terminology, these words may evoke images of a retreat for young people praying to find their path in life, or a novena asking for divine guidance about a major decision, or “come-and-see” visits to a religious order. As the term is generally used, it refers to making one’s life choices based on the will of God, as perceived through prayer and careful consideration.

While at first glance this method appears constricting — to shape one’s life entirely based on the wishes of another — we Catholics, if taught properly, learn early on that conforming to God’s will is not like conforming to the wishes of another human being, whose whims might have nothing to do with our good. God’s will for us is identical with our own fulfillment and happiness — the kind of long-term fulfillment and happiness that is reached by a difficult path, but ultimately brings deeper satisfaction than short-term rewards. Images used to explain this concept include success in art or athletics, where the many pains and efforts involved are crowned with a beauty approaching perfection.1

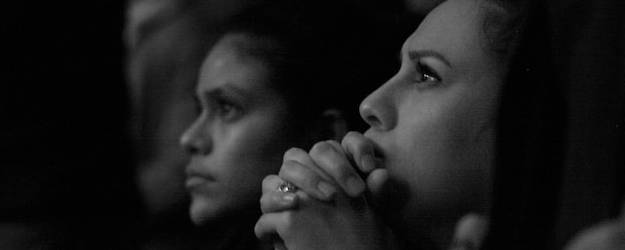

Yet, even if we did learn this lesson, perhaps we could use to be reminded from time to time. For many, vocational discernment is a subject fraught with anxiety, even anguish. Countless souls, especially young people, who are honestly seeking to “follow God’s will” find themselves tortured with questions about whether they are doing something wrong, failing to follow His plan, and possibly ruining the rest of their lives by making some mistake in this area.

The Lord who made peace His bequest to us (John 12:27) and bids us through St. Paul, “Have no anxiety about anything” (Philippians 4:6), assuredly does not wish that seeking to follow His plan should be a cause of so much inner disturbance. Stepping back to examine the problem, and to consider how the Church’s teaching on vocation applies, may be helpful in finding peace amid this tangle of questions.

The Problem

How did discernment become such a stressful subject? Others have written better than I could2 about the anxiety-inducing type of advice, which I have also encountered firsthand, that warns young people of the dire consequences if they fail to correctly figure out God’s will for them, as though God were making a guessing game out of our lives. This way of thinking runs counter to an attitude of trust, which assures us that our Shepherd, our Father, is directing the course of our lives, and that we need not fear choosing wrongly when we choose for love of Him.

Over time, I have become increasingly convinced that the problem has another component. So often, the question of discernment focuses solely on finding one’s way to a single life-changing moment, generally a wedding, ordination, or profession of religious vows. In discussions of potential life paths, one hears language like, “our vocation, whether to marriage, the priesthood, or religious life” — again and again. The rest of life, it is implied, either prepares for or flows from this all-important day.

No doubt, considering these paths is important for “seekers,” many of whom do find their place in one of the above vocations, responding to a tug on the heart. The danger here is that a too-narrow focus on one day, one goal, sometimes even to the point that only that day matters — or progress made toward it — has a way of devaluing all the rest of life.

The consequences do more harm than one might think. If everything depends on the day a ring is put on my finger, and I am not currently moving toward that goal, I am simply wasting time in the present, however good, virtuous, or even necessary my current activities may be. A person may have no way of further hastening the desired goal; for instance, if the goal is marriage, one can socialize and pray in search of a potential spouse, but cannot produce a spouse by sheer efforts. One can still live wholeheartedly for God, working for Him, taking time for Him, giving to Him all the little things that make up one’s life. Yet how likely are we to take this approach if we think that His will for us consists solely in arriving at a single turning point? Ironically, we may become so absorbed in frustration over not being able to do what God may will for us someday that we overlook what He calls us to do now!

The pain is especially great for the increasing number who remain among the single laity. If following God’s will is all about reaching a great life-changing day, and no such day ever arrives, all sorts of bleak conclusions quickly follow: I was not chosen; I have been left behind; I have no place; God has forgotten me. Often, if they come from a Catholic background, these single men and women have grown up hearing a great deal about “finding one’s vocation” in the same sense in which one might speak of finding one’s place in the world. To be told, in effect, that they have no vocation can be devastating.

In fact, the pastoral needs of the single laity are, as can happen when the world changes quickly, a growing vacuum in today’s Church. Luanne Zurlo calls attention to the scale of this need:

Pastorally, singles have fallen through the cracks. At the same time, the number of singles in society and in the Church has exploded. The U.S. Census Bureau reported in 2015 that 109 million (45 percent of American adults) are unmarried, of whom 69 million (63 percent) have never been married). To compare, in 1950, some 33 percent of American adults were unmarried, 20 million or so having never been married.3

On occasion, this dramatic spike in singles is attributed to the younger generation’s inability to make serious commitments. Whatever degree of truth that explanation may have, to explain the issue entirely thus is to dismiss the many fervent, generous young adults, some of whom I have been privileged to know, who have sincerely wished to enter one of what might be called the main vocational paths. Some find that, despite their best efforts, the door never opens; they never find a suitable spouse, or a religious community to which they are called. What can we tell them regarding their vocation? Has God forgotten them?

On this the Lord has spoken clearly. He who attends to each of the sparrows and has numbered all the hairs on our heads (cf. Mt 10:29–30) does not leave out of His providential design any person He created in His image. For each one He has a plan and a purpose. To better understand the relationship between His purpose and our vocational discernment, we may do well to reflect on the concepts of “discernment” and “vocation” in the teaching of the Church and in the lives of the saints.

The Teaching

A search for these two terms in Scripture yields some thought-provoking results. “Discernment” is used to mean something like understanding, the ability to perceive truth; someone who is wise or understands what should be done can be described as having discernment.4 This could be applied by extension to determining the choice of one’s particular life path, but in itself is a broader concept. “Vocation,” also rendered “calling” (“vocation” comes from the Latin vocare, “to call”), recurs several times in the letters of St. Paul, referring not to a specific type of life but to the calling given to all Christians to live the life of Christ, e.g. “I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, beg you to lead a life worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all lowliness and meekness, with patience, forbearing one another in love” (Ephesians 4:1–2; emphasis added). In both cases, what has become narrowly defined in regular usage is used in Scripture in a way that applies to every Christian.

Results in the Catechism are similar. The Index does not even have an entry for “discernment,” and searching for “vocation” yields the following string of sub-entries: “to follow Christ,” “to sanctity,” “to the catholic unity of the People of God,” “call of all by Jesus,” “call of all by the Creator.” Here, again, the term directs the searcher not to specific life paths, but to a universal calling addressed to all who belong to Christ.

At the very end of this list comes “see also: Evangelical Counsels.” The evangelical counsels, namely poverty, chastity, and obedience, are formally vowed by those in religious orders and other forms of consecrated life. At first it might look as though the Catechism is saying, “Is this what you meant by a vocation — this specially set-apart way?” Yet, if it is, even here is a suggestion that the concept of vocation is something greater. The section on these three counsels begins by noting, “Christ proposes the evangelical counsels, in their great variety, to every disciple” (CCC §915; emphasis added).

Naturally, a layperson in the world cannot embrace these counsels in the same way as a religious sister or brother; yet neither are they irrelevant to those outside the convents and monasteries. A layperson is not under an abbot or prior, but still owes obedience to lawful authorities; those in the world must have material things, but are still obliged to share with those in need rather than simply accumulating for themselves; most are not vowed celibates, but chastity is required of everyone. Those who enter religious communities adopt the counsels on a deeper level, yet to one degree or another the calling, or vocation, to these is extended to all.

The upshot is that God calls each person, perhaps through a specific vowed way of life and perhaps not, but always to Himself. The universal call to holiness, promoted more vigorously after Vatican II but always present in Scripture and Tradition, is not only a true calling but our most central, from which all the others flow. St. Thérèse of Lisieux, after wrestling with all the seemingly impossible desires that divine love inspired in her, cried out, “My vocation, at last I have found it . . . MY VOCATION IS LOVE!”5 Hearing these words in the film The Miracle of St. Thérèse, my father commented wryly that if that truth was such a revelation for her, the world was badly in need of her teaching; after all, everyone’s vocation is love.

The Great Vocation: Universal and Personal

To those searching for their place in the Church and the world, a “vocation to love” might sound unsatisfyingly vague. But love, of course, cannot remain a mere abstraction; love worthy of the name takes shape in concrete expressions. Ordinarily, living this vocation of love involves carrying out the many small details of our lives with a generous heart, as best we can and with God’s help. Whatever ways God invites us to deepen our relationship with Him — carrying out tasks at work with a generous heart, a visit with a lonely relative or neighbor, attending daily Mass and regular adoration — are means of living out our own particular calling to the sanctity He desires for us. Each person has been given a combination of strengths and opportunities not given to anyone else, making that person uniquely suited for a particular contribution to God’s Kingdom. If one uses these fully and lovingly in His service, trusting and submitting to such direction as one has been given, one is indeed fulfilling one’s vocation, whatever the particulars of one’s life. This is a true vocation in the sense given by Scripture and the Catechism, our surest authorities.

If further assurance is needed, the saints attest to the universal nature of this calling with the vibrant variety of their lives. Among them we find priests and religious, husbands and wives, and many more who were none of the above: St. Catherine of Siena, St. Rose of Lima,6 St. Giuseppe Moscati, St. Gemma Galgani, St. Angela Merici,7 St. Kateri Tekakwitha, St. Marguerite Bays, Bl. Francisca de Paula de Jesus, Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati, Bl. Carlos Manuel Rodríguez Santiago, Bl. Natalia Tulasiewicz, Bl. José Gregorio Hernández, Ven. Matt Talbot, Ven. Edel Quinn, Ven. Jan Tyranowski (life-changing mentor to the young Karol Wojtyla), and more. These holy men and women demonstrate that holiness is possible in any kind of life for a heart that responds to God’s grace.

All this is not to dismiss the dreams of those who yearn to do and become something more, who feel their lives have still not yet arrived at the fullness of what they are meant to be. After all, this feeling is true for most of us! Paradoxically, however, we only achieve our fullest potential by faithfulness to grace, which manifests itself in small ways in the here and now. Fr. Wilfrid Stinissen expresses this movingly:

Every person comes into this world with a dream of doing something great with his life, something that will make an imprint and bear fruit. God himself inspires this dream. He is, of course, the one who makes the human person great. “You have made him little less than the angels, and you have crowned him with glory and honor” (Ps 8:6). If only we could understand that we can only realize our dream by being totally present to the little and insignificant things we have to do at each moment. We encounter the infinity of God only in the present moment. The more we are recollected in the moment, the more clearly does the eternal now of God reveal itself.8

This, too, is demonstrated in the lives of the saints. Bl. Carlo Acutis created a gallery of Eucharistic miracles which has since been displayed all around the world. Yet his influence is not primarily due to his skillful use of technology; people seldom encounter him first through his website. Instead, the simple marvels of holiness that grace worked in him, from persistently getting to Mass every day to befriending beggars and lonely classmates, have drawn hearts everywhere. Because Carlo responded to the divine invitations extended every day of his short life, he has changed the world — and has surely fulfilled his vocation.

Taking prudent thought for the long-term future, and bringing these thoughts to prayer, is necessary and valuable. The most important point, though, in considering possibilities for our future is the same as when considering any other choice: One is walking hand in hand with a loving Father who will always lead the way and needs nothing from us but our trusting consent. The choice is not a matter of finding a hidden path, nor of fitting into one category or another, but of loving God, trusting Him, and acting on that love and trust. That principle can take as many concrete forms as there are people in the world.

In the end, all discernment comes to the question, “Lord, what would you have me do?” The answer may be surprising, but an answer will always be provided, and it will always be an answer of the deepest, most personal love.

- Cf. Thomas Howard, Chance or the Dance? (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1969), 107. ↩

- Christopher J. Lane, “Trusting in God with St. Francis de Sales,” Crisis, December 30, 2013. www.crisismagazine.com/opinion/trusting-in-god-with-st-francis-de-sales. ↩

- Luanne D. Zurlo, Single for a Greater Purpose: A Hidden Joy in the Catholic Church (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2019), 3. ↩

- See, for instance: “No one considers, nor is there knowledge or discernment to say . . .” (Isaiah 44:19–20); “The wise of heart is called a man of discernment, and pleasant speech increases persuasiveness” (Proverbs 16:21); “And it is my prayer that your love may abound more and more, with knowledge and all discernment, so that you may approve what is excellent” (Philippians 1:9–10). A list can be found on biblegateway.com by selecting the desired Bible translation — the above were taken from the RSV-CE — and searching for “discernment.” ↩

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Story of a Soul, third edition, ed. John Clarke, O.C.D. (Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1996), 194. ↩

- Although St. Catherine and St. Rose, in their black and white habits, are often mistaken for nuns, they were in fact Third Order Dominicans who pledged themselves to Christ by private vows of virginity. ↩

- The group that St. Angela organized eventually developed into the Ursuline Order, but this stage came only after the saint’s death; Angela herself died as a single laywoman. See “Saint Angela Merici,” Franciscan Media, www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-angela-merici/. ↩

- Fr. Wilfrid Stinissen, Into Your Hands, Father: Abandoning Ourselves to the God Who Loves Us (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, CA), 61. ↩

Excellent analysis of discernment.

I’ve taken these factors and integrated them into conflict resolution, peacemaking. The idea advanced in my Divine Collaboration protocol is that we grow most in discernment of the Will of God in the midst of conflict and tribulation, when the Will of God becomes a major factor in resolving conflict.

The substack Divine Collaboration takes up these ideas.

I’ll come back to this again, but on the initial skim, an excellent article. A pivotal moment for me in my own discernment was to realize that vocation is not just about giving love, but also how we receive love ourselves, since we can’t give what we don’t have. Since deciding to pursue marriage, I’ve also come to realize the importance of the daily striving for holiness and virtue, step-by-step. When we run toward God and give ourselves fully to Him in trust, our vocation becomes clear.