Biblical theology of creation is applicable in pastoral ministry, because of its rich cornucopia of imagery and metaphors of myth and apocalypse, imagination and paradoxes employed in demonstrating God’s omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence in cosmogonies. Such a discourse substantiates God’s creative ability, power over chaos, artistic skills, and continuing relationship with His creation. Creation is seen as a sort of a battle between God and rebellious elements and God’s overriding victory over them (Ps 103/104:5–9 NRSV).

The theology of creation has affinity with distressful human situations, such that its application reminds us of God’s unchallenged authority, sovereignty, and power over chaos and evil, giving an assured hope of victory to the suffering. Unfortunately, many Christian pastoral caregivers and spiritual directors rely solely on the traditional theologies of salvation and grace, either completely neglecting or sparingly utilizing the biblical creation theology in pastoral care, ministry, spiritual practices, and spirituality. However, the prophetic theologies of salvation and grace which are normally employed by pastoral theologians are grounded in creation theology — giving the notion of re-creation, a new creation, or new life. Thus, appropriating creation theology, apocalyptic imagery, myth, and metaphors in pastoral ministry for those experiencing any form of pain, stress, and suffering in their mythical and prosaic life is an efficient means of providing pastoral care.1

In creation theology, we appreciate the outstanding power of God at work to a higher magnitude in comparison to the salvation-grace theology. Here the minister and pastoral care provider can assure the care receiver or believer about God’s creative power at work, which He fully exercises in creating something new in every stressful human situation.

The creation account in the book of Genesis provides important guidance about life and a blueprint for spirituality, by emphasizing God’s active role in human history. In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve had an open relationship with God, but when they lost friendship with Him, this resulted in a strained, disordered, and chaotic relationship — a reminder of the tehom before creation (Gen 1:2). As a result, humankind has been searching for God, until He is finally revealed in His incarnate Son, Jesus Christ.

It is this orientation toward spirituality that helps an understanding of chaos and God’s power over it in the mystery of human suffering and misery. Thus, incorporating themes from creation theology into pastoral ministry and caregiving is an essential way of meeting pastoral care needs and challenges in a world torn apart by pain and suffering.

Human Suffering, Chaos, and Pastoral Care

In everyday pastoral situations, you may hear people who are struggling to survive tragedy: ill health, spiritual attacks, persecution, grief, the death of a loved one, or disappointments, expressing anger against God. They believe that God is punishing them, or is unconcerned about them (Job 19:6–12, 21; 23:1–9, 16–17). How do we provide meaningful pastoral care for such believers or help them know God cares, or help them keep up with their spiritual life amid the chaotic throes of their prosaic lives?

The solution is to apply the theology of creation to challenge their thought and faith, and understand that God’s creative power will bring stability and order to them, as we learn in Genesis’ creation theology. We know that our relationship with God does not preclude any degree of suffering, diseases, or tragedy, but the good news is that God will always tame anything that threatens our peace.

What then is pastoral care? “Pastoral care” is the practical expression of the Church’s ministry of love, serving the needs of the community of believers in various ways.2 Pastoral care ministry provides special spiritual health, counseling, and education to people relative to their peculiar needs. It provides spiritual support services like counseling, visitations to hospitals, homes, prisons; palliative and bereavement care, prayer sessions, catechesis, memorial services, administration of sacraments and much more.

The Doctrine of Creation: God’s Relationship with Creation

Generally, we see the idea of God as the Creator of the universe in the Hebrew Scriptures (cf. Gen 1–2; 8; Ps 74:12–17; and Job 38:1–42:6). The God who creates (in the Old Testament) is the same God who is revealed (in the New Testament) as the Redeemer and Savior. God does not distance himself from creation, but relates to it and sustains it.3 God’s ongoing relationship with His creation is described in terms of transcendence, immanence, providence, and economy.

“Transcendence” means that God is not a part of nature, nor do we identify nature and God as being of the same substance. God is over and beyond and is separated from his creation in all aspects.4 “Immanence” means that God is not a distant, absentee God but active in the world. He is intimately present in and with His creation in time and in space (Ps 139:7–10). There is no moment when any creature could evade the presence of God. However, God is not identified with the created order.5

By “providence,” we see God’s continuing action in preserving, supporting, and governing creation in accord with His plan and purposes for human salvation.6 This means that God works through nature to provide for His creatures, and that nature expresses God’s will. Other terms used for essentially the same concept are: the “sovereignty” of God over nature, God’s “governance” of what appears to be natural processes, or about God’s “concurrence” or “cooperation” with natural processes, and God’s “preservation” of nature as He employs them to accomplish His purposes.7

Finally, by God’s “gracious self-limitation” or “economy,” God allows creatures their own integrity, almost always working through His normal governance of nature. This allows us to live in a consistent world, meaning we do not typically get obvious evidence of God at work — we do not pick up a rock and see it stamped, “made by God.” It might make our apologetics easier if we did get such evidence. But we can look at the humility of Jesus as God’s incarnate Son, and perceive that God is mostly hidden in the workings of nature.8 The term kenosis (Greek) is used to talk about God’s self-limitation, when talking about Jesus’ total self-giving and emptying of himself, humbly taking the form of a servant (Phil 2:7).

How does the doctrine of creation affect spirituality and pastoral care ministry? The doctrine of creation affirms that creation is good, that something can be known about the Creator, and that creation is sacred to God. The goodness of creation implies that there is no need to withdraw from the world in order for a person to get closer to God in holiness.9 The reason is that the world itself is a microcosm of the temple of God.10

Human beings are required by God to actively participate in the world (Gen 1:28; 2:15ff) as required in the temple service (Gen 2:3; Exod 20:8–11). Mankind has the spiritual and moral responsibility to care for the world (the environment, all creatures, and every human being; see Gen 1:28–30), since God’s creative power is constantly at work in the universe and within us.11 If God can turn chaos into good, disharmony into harmony, disorder into order, then logically, He prevails over any form of human suffering and miseries too. Whatever sickness, diseases, dread of the foe, or any negativity a person experiences, that person can confidently invoke the power of God to ameliorate the situation towards a new creation, a better life, peace, and harmony.12 The point is that chaos is neutralized in worship by the invocation of the power of God.13

Thus, the doctrine of creation animates spirituality and inspires confidence and hope that something can be known about God Himself through contemplating creation, which He creates good. To study nature, whether through science, physics, biology, chemistry, or mathematics is to learn something about the wisdom, greatness, and majesty of God whereby we can conclude that, “creation evokes a sense of wonder.”14 All these would lead a believer to a deeper faith in God, thereby enhancing spirituality. Therefore, the doctrine of creation implies care and preservation of creation and the Sabbath rest.15

Biblical Theology of Creation

God has a purpose for creation, because everything that He creates is good and reflects His wisdom and glory (Ps 19:1–2). This is why creation must be used to glorify God and to celebrate His sovereignty, and enthronement.16 God intends that humankind, His stewards of creation shall serve, worship, love, remain loyal, and be in joyful union with Him.17 God does not create and then abandon his handiwork — He creates and constantly sustains it. God is intimately involved with His creation; is present to every creation everywhere and moment, so is all-knowing, and almighty (Ps 139:7–10).

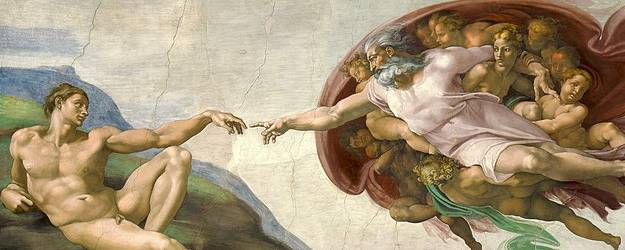

In the book of Genesis, God freely wills, lovingly creates the world, and justly sustains it. God creates all that exist “out of nothing,” ex nihilo, through the creative power of His word; by His commands (Gen 1:1–3), except human beings, whom He fashioned from the earth (Gen 1:26).18 This means that He can remold any predicament of mankind into something new. So, in any form of human suffering, we should not feel as if God has abandoned us and cares less about us. Our confidence is in God, more than a mother; God will never forget His children (Isa 49:15; Jon 4:11).

The priestly account of the creation story of the heavens and the earth in the Hebrew Scriptures gives special importance to human beings among God’s creation. It is only with the creation of humankind that God said: “Let us make humankind in our image and after our likeness” (Gen 1:26). Thus, the image and likeness in the creation context in the book of Genesis are key terms in understanding human nature, human life and its dignity and responsibilities in the world. Besides, this “image-likeness” has its consequent implications in humanity’s care for the earth, and in the use of human freedom.19

The term “image” refers to some concrete, external form of representation. Thus, humanity is established as God’s representative on earth in a unique way — caring for the rest of creation.20 The term “likeness” refers to an internal relationship and similarity. Human beings are only flesh and finite beings, yet God endows them with a special capacity or ability to search for Him and relate with Him.21

In the priestly tradition’s account of creation (Gen 1:1ff), God uniquely endowed human beings with the capacity and ability to maintain an intimate relationship with Him. Thus, the uniqueness of human beings from all other creatures is defined primarily in relationship to God and derives its meaningful existence to God alone in terms of this unique relationship.22 Based on God’s relationship with mankind, there is a consequent capacity and responsibility for people to be each other’s keeper (Gen 4:9) as we see in pastoral care ministry (Matt 25:40). It is in caring for one another that all human beings meaningfully participate in God’s creation, maintains, sustains, and preserves it. This is why pastoral care ministry is at the heart of biblical theology of creation.

Creation: The Art of Re-creating Chaos into Orderly Life

The concept of re-creating chaos into new life, using biblical creation imagery, imagination, paradoxes, and metaphors can be a helpful tool in pastoral ministry. In the prosaic and mystical nature of life, sufferers do question whether God has any power over Satan and evil, at all (Job 2:9). It is evident from apocalyptic creation imagery (Pss 104; 148) that, God allows both good and evil to coexist, so that he may show His creative power and sovereignty over history (Gen 8:21–22; 9:13–17; cf. Matt 13:24–30, 36–43). Thus, believers celebrate not their defeat in circumstances of life and death, but God’s victory over chaos.23

Throughout the history of Israel, God’s victories were celebrated, namely, in the crossing of the Red Sea and their entry into the Land of Promise (Exodus 15). Centuries later, the psalmists apply the theology of creation and apocalypse in dealing with chaos (Pss 74:12–17; 104; 148). They show that God has no equal; He fought and defeated chaotic forces, so that good may triumph over evil, sin, and death.

In pastoral ministry and care, believers experience demonic attacks, evil forces, curses, diseases, and misfortunes which they think strip them of the pleasures of life (cf. Job 1–2). Therefore, such victims of malediction, imprecation, or ill-omen need a stronger power to fight on their behalf and deliver them as God delivered Israelites from Pharaoh and his charioteers in the Red Sea (Exodus 15). Suffering a terrible disease or dealing with the death of a loved one tells us that good and evil co-exist, but God’s power will bring harmony, order, and restoration of life; hence, with steadfast faith, we can appeal to Him to act quickly, that we may celebrate His Sovereignty and Victory.

The Holy Sacrifice of Christ at Calvary is one way of celebrating God’s Victory over sin and death, which offers us redemption and salvation, reinforcing our faith and hope (Mark 14:22–24; 15:33–38; Matt 27:45–53; Luke 23:44–46; 1 Cor 11:23–26). Through reading of sacred scripture, spiritual exhortations, sermons and homilies, ministers of God deliver messages of encouragement in communal and individual celebration of God’s Victory and success.24

All these lead to new possibilities, renewed trust, and deeper union with God and people. Through Christ, the Victor over sin and death, we can now implore God to set us free from the bondage of sin and death, deliver us from demonic possessions, and every onslaught of the enemy. By His incarnation, Christ shares in the misery and plight of all humanity, understands our frailty and is desirous to make our burdens His own (Matt 8:17; cf. Isa 53:4).

In applying biblical typology of creation myths and apocalypticism to pastoral caregiving, we can better theologize about the phenomenon of surviving a tragedy or a misfortune in terms of re-creating one’s life by means of God’s grace, which calls for endurance and patience. Since the battle is the Lord’s (1 Sam 17:45, 47; 2 Chron 20:15), those for whom the Lord is fighting must remain calm and wait on the Lord — Prayer, faith, trust! Thus, we can argue that it is inadequate to simply go through a tragedy by means of God’s grace, rather the victim ought to be recreated by God’s grace in the midst of the tragedy (Isa 64:8). Thus, re-creation symbolizes a new event in one’s life. Therefore, the new event (tragic survival) is more than simply getting through a tragedy or a desire to do good or keep evil from happening.25

Thus, using the theology of creation or mystical explanation of human tragedy, we may come to appreciate God’s exercise of His freedom, justice, love, power, and absolute sovereignty over chaos in one’s tragic life, thereby putting things in their right perspectives. If this concept of creation and recreation can be tactically introduced in pastoral caregiving, for example care of the sick, it makes sense to address the real-life situations of what people are experiencing. To say the least, many times, the pastoral caregiver is detached from the realities of what the suffering care-receiver or believer is experiencing. The idea of recreating a reality is something difficult to incorporate into pastoral conversations, social intercourse, or caregiving. However, theologians should be bold and prudent in furthering this concept for practical theology instead of arbitrarily reverting narrowly to the traditional theology of salvation and grace.

New Creation and Life in Christ Jesus

We already see that the theology of creation touches on God’s display of creative power. His absolute command in offering new life out of nothing, harmony and peaceful coexistence of things, and His Sovereignty over chaos calls for celebration of His enthronement.26 It is also important to note that the theology of grace and salvation is mainly the activities of God and His favor towards people in bringing them into rightful relationship with Himself.27

Normally, the theology of grace and salvation deals with the issue of sin, disobedience, offering sacrifice, atonement for sins, redemption, liberation, and communion with God. This concept of grace and salvation connotes the idea of a righteous person’s merits of God’s favor and blessing of sinful human beings for salvation, often preconditioned by redemption. Although salvation and grace are free gifts of God, they are costly and not easily attainable. Since grace does not operate in a vacuum, human cooperation with grace will benefit a person’s salvation.28

Jesus, the first-born of all creation, is the life of the new creation. His incarnation, atonement, and redemption brought about this new life based on grace to enhance human salvation. He is our life, peace, reconciliation with God, and with all creation. In Him, everything is redeemed and renewed through the paschal mystery (Col.1:15–20). The paradise once lost is regained in and through Jesus Christ. By the incarnation of Jesus Christ, His atonement for sin, sacrificial death, and resurrection, we are redeemed. Through baptism into His paschal mystery—we are born to new life and become coheirs with Him. By Jesus’ paschal mystery, we are offered the gift of grace and the new creation (John 1:12–13; 20:1, 21–22). In Jesus Christ, creation becomes perfect and new in justice, charity, and peace. We become a new creation, for the old order passes away.

The prologue of John’s gospel (John 1:1–18) and the resurrection narrative (John 20) tell us how His incarnation and resurrection offer new life. The description of these poetic texts bears many semblances with the creation story in the book of Genesis. It is noted that John’s gospel demonstrates how things have been created (see Gen 1:1) and made new in Christ (John 1:1, 12–13). In the book of Genesis, God created light on the first day and on the sixth day, He created mankind and breathed into him, and rested on the seventh day. Similarly, Jesus, the proto-Adam, was killed on the sixth day, remained in the tomb on the seventh day, but rose again on the first day of creation of light (Gen 1:3–4; cf. John 20:1). Jesus is the light of life, the light of the world (John 8:12; 9:5; 12:32), and the first fruit of the resurrection (1 Cor 15:20). Through the mystery of Jesus’ death and resurrection, creation has been made new.29

When God formed the man (Adam) from the earth, he breathed into his nostrils the breath of life and animated him (Gen 2:7). The two creation accounts in the book of Genesis (cf. Gen 1–2) reflect the re-creation of the new man.30 The Risen Lord, on the evening of His resurrection, breathed on the disciples and gave them the Holy Spirit,31 the principal life of the new man.

This understanding re-enforces our assertion that creation theology must be spiritualized in pastoral caregiving and spiritual practices. This means that we can cooperate with this gratuitous gift of God, notwithstanding the nature of chaos in our life, to reorder our life and become more resilient. In this sense, even in any tragedy, the sufferer must understand that healing, harmony, peace, or new life may result from re-creation by grace and not just going through grace. This calls for fortitude and liturgical life — persistently trusting in the Lord, praying, singing praises, and continuous thanksgiving (Col 3:15–17).

Appropriating Spirituality of Creation Theology

We should employ creation and apocalyptic imagery in pastoral discourses and ministry to help the sufferer interpret the tragedy being experienced. In making use of imagination, paradoxes, metaphors, and other literary devices, the mystery of suffering and tragedy is demystified. Such an interpretation of suffering takes the believer back to the primeval times, when God was creating the world. This approach is helpful in giving the sufferer a sense of control over any present chaotic situations. There might be a breakthrough when unexplained tragedy is perceived this way. This may slowly lead the person experiencing suffering to discern God’s saving help and control as time unfolds to bring order to the disastrous chaotic state.32

Just as we see God’s power over the chaotic water in creation (Gen 1:1–3), so in human suffering, we can appeal to God to act quickly on our behalf and get rid of chaos which befalls us, through our pastoral care ministry. We can also make use of God’s own words, and remind ourselves of His past achievements among other things, and be assured that He will intervene in our case (Pss 22:5–6; 44:1–4; 136).33

Since men and women are created for God, to serve, love, and worship Him, they must remain in a loving relationship with Him for happiness. This purpose or end of our existence is appropriately exercised through worship and liturgy by celebrating God’s majesty, sovereignty, and kingship.34 In celebrating God, the Absolute Good and end of all life, men and women fulfill the purpose of their existence and are ordered toward a peaceful coexistence with the rest of creation, with themselves, and with God. We demonstrate our knowledge of God by relating to Him through spiritual practices and the way we provide care and support for one another in any sphere of life, even amidst the uncertainties of life.

In the sacred liturgy, therefore, through Jesus Christ our Lord, we bring before God our personal difficulties, pains, sicknesses, chaos, joys, and needs, spiritually looking for a breakthrough in the storms of life. In every liturgical gathering, those who are experiencing both sufferings and joys are in the house of God looking for harmonious creation, either in its beautiful form or in the form of re-creation. How do we accomplish both within the same worship experience?

The creation sequence analogies tell us that in the liturgy, God puts the days back into sequence, plants, sea monsters, the animals or chaos back in place. We go about reminding ourselves that the sun, moon, and stars are regular in their orbit and courses, even though it seems that all is out of control. The liturgical rituals tell us about re-separating what has confusingly come together into a mess and is being animated through the paschal mystery of Christ. In other words, every liturgical celebration is the act of God in which we celebrate His power, kingship, majesty, and sovereignty over chaos in reordering and recreating new things (Ps 74:12–17; Dan 3:57–88). Hence, spiritualizing theology of creation is a sure way of experiencing God’s saving power and patiently enduring any form of tragedy, ordeal, and chaos in life.

Applying Creation Theology in Pastoral Ministry

God’s creative power is realized in our pastoral ministry and care for people at all stages of life. From conception to natural death, the Church provides pastoral care to people, the sick, the dying through prayers, counseling, preaching the word, anointing of the sick, so that the sacraments may animate life and reinforce union with God. In people’s real-life situations, they experience chaos, which must be confronted by invocation of God’s sovereign power and authority, just as it was at the biblical creation times, when chaos gave way to orderliness and life at God’s commands. All that destabilizes the equilibrium of the human condition (synonymous with chaos), such as illness, sickness, sadness, distress, gloom, demon possessions, sin, and death must be combated that life may emerge.35

Whatever affects the body concerns the soul, fortunately these cannot be separated. Thus, preservation of the entire human person is inevitably the aim of pastoral care ministry. This is why pastoral ministry involves God and Jesus in every aspect of human life. For example, through inculturation, some Catholic dioceses in Ghana design rites for celebrating the human life cycles (stages of human maturation) with accompanying rituals.36 At every stage of life, concrete religious rituals are performed, while initiating the person into that state of life, thereby breaking chaos and enforcing harmony, as in the “outdooring”37 ceremony of an infant. Pastoral ministry and caregiving are relevant to puberty rites, which initiate a person into adulthood, entrust responsibilities, and ward off the threat of death because the believer can “confess that Jesus Christ is Lord” (Phil 2:11) — death ceases to be a threat to faith witnessing because the disciple no longer fears death nor martyrdom, even when it comes.

The Sacraments of initiation — Baptism, Confirmation, and the Eucharist — also replace potential chaos with order into the Mystical Body of Christ as full members (Rom 6:3–6). Marriage thwarts the sin of promiscuity and living out one’s covenant relationship. Anointing of the sick, confession of sins, penance, and reconciliation break the effects of sin, give inner, spiritual, physical healing, and restores life to Christ. Christian funeral rite celebrations certainly confront chaos in its most potent form by transforming the fear of death into victory and everlasting reunion with God.

Within these liturgical services and pastoral care, those who attend and participate re-live, for instance, their own baptisms and marriages and thus reaffirm the creative order around them. Confession of sin is encouraged at these celebrations to enhance spiritual benefit. It is through reconciliation that our life is restored to its original state, and we get rid of the chaos that has ensnared us. All this puts us back into the Garden of Eden, even if temporarily, by sanctifying grace. Since God’s relationship with creation is ongoing, we have confidence in God’s creative power to ameliorate any human chaotic situations for we are like clay in His hands (Jer 18:6).

Conclusion

People’s life experiences are intertwined with faith in mystical ways. Paradoxes and contradictions exist in life. What people experience in real life, they express in their religious or spiritual life endeavors because the human person is a compact unity of body and soul. In other words, history exists alongside faith and religious myths or mystery. Myths express religious truths beyond human words, experiences, and scientific intricacies or proofs.38

What baffles people’s minds leads them to explore, express, and interpret it in faith praxis. Life is a mystery, which we live and try to decipher and unfold. The best way to unfold it is living the apparent contradictions of life, which is not always pleasant to talk about, but we should not consider them as a curse, defeat, punishment, weal or one’s downfall or personal demise. For a time, it may seem like chaos, but at other times it provides an orderly orientation for one’s life. Thus, faith and knowledge of God are the keys to overcoming the contradictions of life in this challenging world of secularization, materialism, consumerism, and atheism.

It is important to remind ourselves of God’s power, when He created the world, and through His Son Jesus Christ defeated chaos and brought about orderliness and new life. The knowledge of this same divine power should guide and harness pastoral care and ministry. In combating any human tragedy, we pray to God the Father and His Son our Lord Jesus Christ in the unity of the Holy Spirit, hoping that the power of God will eliminate all chaos in mankind. By uniting human miseries, contradictions, and tragedies with Christ’s paschal mystery the creative power of God is best experienced. In the process of improving human tragedies, God’s power eliminates the chaos experienced by people and gives way to orderliness and a new life in Christ, where there will be no more suffering and death.

- Mythical life is a life that is beyond ordinary spheres of existence, but is spiritual and supernatural. Prosaic life is ordinary, everyday life, sometimes interrupted by some drama or crisis. ↩

- Donald K. McKim, ed. “The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms” (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 2014), 4, 230, 244. ↩

- This view is well explained by Yahwist tradition, in the OT, which emphasizes God’s intervention in human history. ↩

- McKim, 4, 23. ↩

- McKim, 23. ↩

- McKim, 216. ↩

- Collins Jack, “Miracles, Intelligent Design, and God-of-the-Gaps,” Journal of Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 55 (1), (2003): 22–23. ↩

- Jack, 23. ↩

- Alister E. McGrath, Christian Spirituality (Maiden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1999), 35. ↩

- David Jon Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil: Jewish Drama of Divine Omnipotence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 78. ↩

- Pope Francis, Laudato Si’: Encyclical Letter (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2015), #123. See also, Pope Francis, Amoris Laetitia: Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, Publishing Division, 2016), #39. ↩

- Timothy J. Allen and G. Harold. Koenig, A Theology of God-Talk: The Language of the Heart (New York, NY: Haworth Press, 2002), 91. ↩

- Levenson, 100, 121. ↩

- “When I look at the mountains, the valleys, the sea, stars at night, I know that you’re God . . .” which is part of the wonder of God (see McGrath, 36). ↩

- God creates everything for Himself to celebrate His sovereignty. ↩

- Allen & Koenig, 49, 145. ↩

- The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC #1). ↩

- See John H. Walton. The Lost World of Genesis One (Downers Grove, CA: IVP Academic Press, 2009), 42. ↩

- John R. Sachs, The Christian Vision of Humanity: A Basic Christian Anthropology. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1991), 13. ↩

- Sachs, 13. ↩

- See Sachs, 14; cf. CCC #1. ↩

- Sachs, 14–15; McGrath, 35–36. ↩

- Allen & Koenig, 124–125. ↩

- Dei Verbum #11; see John 20:31; 2 Tim 3:16; Heb 4:12. ↩

- Allen & Koenig, 125–126. ↩

- Levenson, 29, 37, 127. ↩

- McKim, 115–116, 342–347. ↩

- Heb 10:26–27; Jas 2:17. ↩

- Nicholas Thomas Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2013), 1473. ↩

- This gesture of sending forth of the Spirit in John’s gospel account means that the resurrection-ascension occurred on “one day.” ↩

- The Holy Spirit forgives sins (chaos), gives life (re-creation), and reconciles us with God. Mankind will no more be totally alienated from God through sin, for the Spirit will bring orderliness in human relationship with God. ↩

- Allen & Koenig, 126. ↩

- Confer, Levenson, 100–102. ↩

- Theology of the sabbath regulation and rest (Genesis 2:2–3). ↩

- In the book of Genesis 1:3, God commanded things into being: “Let there be . . . and so it was.” ↩

- Known in psychological terms as the “rites of passage.” ↩

- Outdooring is a birth initiation ceremony among Ewe people in Ghana and some other communities, where a name is conferred on a child on the eighth day of birth to ward off the potential chaos of losing one’s life/parents or not having a “Christian” name. ↩

- Peter M. J. Stravinskas, “Catholic Dictionary” (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Inc, 2002), 489; See also Allen & Koenig, 64, 69. ↩

Moses,

You are opening the way for the world to enter into communion with one another in Christ. Creation spirituality as you describe it is a stepping stone on the way. I have questions to consider as we open up the Way of Jesus to all. Why are we limiting pastoral ministry to believers? What about the seekers who are not believers, can they benefit from creation spirituality? Is there a place for the psalms of cursing and lamentation in creation spirituality? Can creation spirituality begin a journey of understanding the trinitarian God of the Christians? There are so many more questions to explore. Thank you for opening a door to that exploration.