In cities across the country, people are rioting in the streets in response, they say, to the death of George Floyd, who lost his life on May 25, while police, in Minneapolis, apprehended him on suspicion of passing counterfeit currency — a non-violent offense in which, it would be reasonable to suspect, he may well have been a victim himself.

The abuse of public trust by those responsible for law enforcement undermines the basis of civil society. So, protesters rightly called for redress, and soon after the incident, the full weight of government, at the federal, state, and local levels, came to bear upon those involved.

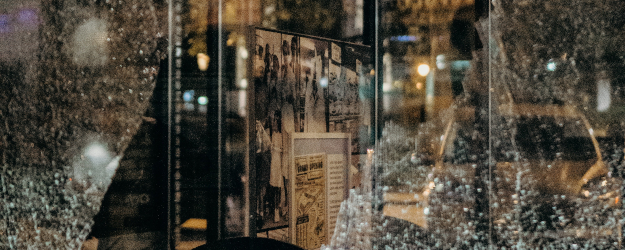

No Justice, No Peace

Then the riots broke out, with the usual mantra: “No justice, no peace!”

The voices of countless legitimate protesters who deserve to be heard were drowned out, yet again, by those who presume to speak in their names but advance an agenda all their own.

For these interlopers, it seems, treating excessive use of force by police as a crime, removing the officers accused of it from their positions of trust, and prosecuting the principal actor for murder isn’t enough. The determination, a few days later, to bring charges against all the officers present during the incident did nothing to quell to the violence, either.

While a survey conducted by the CATO Institute shows overwhelming consensus across ethnic groups, concerning a slew of policy measures pertaining to police reform, the rioters who have taken ownership of the protests, seek an unspecified remedy for their grievances from an undefined party, and until those grievances are satisfied, they feel justified in lashing out at the impersonal “Other”. We see by their behavior that this “Other” is represented in their minds by the very structures of civil society and, concretely, by men and women in uniform, courthouses, civic monuments, places of worship, and businesses — and even by the innocent bystander, whom they set upon for the offense of merely being someone else.

It’s difficult to see how any of this behavior could result in anything good, but even if it could, that fact wouldn’t justify it. It’s gravely evil to harm the innocent, directly and intentionally, and it’s gravely evil to undermine the fabric of civil society, since human beings are, by nature, social animals. That’s what rogue police officers do when they abuse their authority and it’s what rioters do when they lash out against the social order under which rogue officers could be brought to justice.

So, while, under narrowly defined conditions, armed insurrection can sometimes be justified, riots never can. They can’t be justified because, by their very nature, they destroy the conditions for a just society.

An Important Distinction

But, what’s the difference between a riot and armed insurrection, anyway? Isn’t that just a distinction history leaves to the victor?

No. Armed insurrection is directed against a government by the people they govern. A riot is directed against the very idea of authority and social order. It’s anarchistic in nature and, for this reason, necessarily destructive of the public good. It involves doing harm to innocent people, to the recourse they enjoy to the social technologies that provide them safety and security, to their means of livelihood, and to the buildings and infrastructure upon which they rely for health and well-being in their daily lives.

Anger is no excuse for doing this kind of harm, even if the anger itself can be justified.

The Moral Roots of a Riot

Now, in the Christian tradition, unbridled anger is numbered among the Capital Sins. It’s a deep-seated character defect that plagues many of us as a consequence of the world’s fallenness. Those who suffer from the Capital Sin of anger don’t become angry because the world is fallen and bad things happen in it. Rather, because the world is fallen, many of us are born with an inclination toward unbridled and misdirected anger.

Again, a “Capital Sin” is an inborn, deep-seated character defect. We all have these kinds of character flaws. We just don’t all have all of them, or not to the same degree.

Envy, too, is numbered among these kinds of “sins”. It involves the tendency to compare one’s own condition to the condition of others — to look over the fence into our neighbors’ yard and see what they have that we don’t. The envious person is given to see himself as being deprived of what he thinks he deserves and to see others as the reason he’s been denied it. The prosperity of others — real or imagined — is perceived by the envious person as the reason for his own unhappiness.

When people riot, these character defects bear their poisonous fruit.

What does the gas station or the pastry shop have to do with the death of George Floyd? What do the rioters achieve by burning them to the ground? What has the man in the intersection done to deserve hospitalization or the loss of his life? Have the rioters repelled an aggressor or merely destroyed another person’s property and murdered someone they didn’t even know?

Aristotle reminded us that it’s an easy thing to be angry, but that a vicious person doesn’t know how to be angry correctly. It takes virtue to be angry at the right time, for the right reason, and with the right intensity, to direct our anger at the right person, and to remain angry only for as long as necessary. Rioters don’t do any of that. They’re vicious.

The Rioters Are in the Wrong

The rioting we see in cities across the country today is a revolting and embarrassing sign of the vicious moral state of those who engage in them.

Protest is one thing. Riot is another.

Those who riot haven’t learned to temper their inborn character defects with the contrary virtues that make a peaceful society possible but, instead, have given in to their vicious inclinations and are now ruled by them.

Once again, in undermining the civil order and destroying property, the rioters take from others the causes and conditions of their well being. Such activity is born of envy. They associate their own unhappiness with the happiness of others and seek to find some consolation in the misery they inflict on those around them. So, where envy and anger intersect and become one and a riot erupts, in destroying property and burning down storefronts, the rioters deprive their fellow human beings of their livelihood. Whether they attempt to kill an innocent person directly, as they have done in some cases, or else do so indirectly by taking from an innocent person his or her means of support, the rioters commit a sin that, according to the Bible, cries out to God for vengeance.

The victim in this story — the poor, the oppressed — is the person lying beaten in the street, not those who stand over him with bricks and sticks of lumber. It’s the shop owner who’s lost his means of support, the single mother with no job to come back to, or the elderly woman left homeless because rioters burned another neighborhood to the ground.

Make no mistake about who’s in the wrong here. It’s the rioters. What they do is evil, and they can claim no moral high ground for themselves. And when high-profile clerics goad them on by suggesting moral equivalency between violent riots and peaceful protests, even as churches are vandalized and set on fire, and when virtue-signaling celebrities and politicians post bail for that small fraction of rioters the outnumbered, overburdened peace-keepers still managed to apprehend, they’re actively encouraging those actions. They’re all complicit in the same evil: both those who riot and those who encourage them and enable them.

No Peace, No Justice

George Floyd would get no justice in the world the rioters and their supporters seek to inaugurate in his name. How could he? How could anyone? What recourse would we have? If the rioters get their way, they’ll have burned it all down and there’ll be nothing left but the rule of force: the strong over the weak.

That’s the definition of injustice. It’s diabolical.

Dr. Bulzacchelli, your article is an excellent presentation of Aristotelian Ethics. The big problem is you start with the wrong assumption. The demonstrations are not just about Mr. Floyd’s murder. If you listen closely to what is being said you will hear it is about systemic racism. There are many assumptions in the article that I would question. Let me just mention one other that relates to my experience. You assume that burning down a storefront and murdering innocent bystanders is evil and diabolical. I agree these are evil acts. The problem is you infer it is permissible if committed by the military. When I was 16 years old, in 1956, I joined the Michigan National Guard. I was trained to kill with a 57mm recoilless rifle. As I was being trained to kill we sang vile songs about killing to protect our women, not about protecting the order of society. We were being made into warriors whose purpose is to kill. If we missed our target and killed an innocent family it was collateral damage. Collateral damage was the death of innocent people, no compassion was encouraged. I looked at the arguments based on Aristotle about just war theory. They made no sense to me. My decision at that early age was I cannot kill. I believe Jesus Christ gave us a WAY that excludes the deliberate killing of human beings.

I do not assume that burning down storefronts and murdering innocent bystanders is permissible if done by the military. Your own horrible experience notwithstanding, Just War theory developed from the careful thinking of people like St. Augustine, who recognized the defense of the polis was a duty of the civil authority, even though the exercise of that duty sometimes involves killing. Murder is distinguished here not only on the basis of who performs the action but on the basis of what the action is. Just War theory does recognize a category of “collateral damage,” but such damage can never enter into our intentionality and it must always be avoided if it is possible. If it can’t be, one must still assess whether the direct object of the action is worth that cost, and often, the answer to that question is no. Consider here, for example, that when people declare that they are no longer a part of the United States and expel the rule of law, taking over a public building and setting up territorial boundaries, we might say that they have engaged in an act of war. Objectively, the use of military force to suppress such an act and liberate American citizens from foreign rule, restoring constitutional governance for them, would be justifiable, simply speaking. But such a response was not initiated. Why? I suppose it might have been that the collateral cost of doing so was too high to pay, and that it was hoped that a less destructive solution could be found, as, indeed, it was.

imagine being so completely coddled by middle class comfort and privilege that you call poor and desperate people betrayed by a satanic economic and violent political system “evil” because they burned down an autozone and a target. the corporations will deal. whether the author of this can is not so certain.

Richard, Read this quote from Alex Kotlowitz, then revisit your assumptions about anger. Please let me know what you think. I live in Chicago. I have no solutions, but know what is happening in our neighbourhoods is about who we are as people.

“There was a moment when we were filming the documentary The Interrupters when Ameena Matthews, one of the three violence interrupters whose work we chronicled, reflected on what she called “the thirty seconds of rage.” She described it like this: “I didn’t eat this morning. I’m wearing my niece’s clothes. I just was violated by my mom’s boyfriend. I go to school, and here comes someone that bumps into me and don’t say excuse me. You hit zero to rage within thirty seconds, and you act out.” In other words, these are young men and women who are burdened by fractured families, by lack of money, by a closing window of opportunity, by a sense that they don’t belong, by a feeling of low self-worth. And so when they feel disrespected or violated, they explode, often out of proportion to the moment, because so much other hurt has built up and then the dam bursts. They become flooded with anger.”

Kotlowitz, Alex. An American Summer (pp. 18-19). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.