St. Francis de Sales in his excellent book, On the Preacher and Preaching, declares emphatically: “We must adhere to method in all things; there is nothing more helpful to a preacher, makes his preaching more profitable, and is so pleasing to his hearers.” His book makes it clear that what St. Francis means by method is an organizational structure for the homily. Consequently, he outlines several ways that he uses to structure his homilies. Another understanding of the term “method” refers to the whole homily preparation process. In that regard, both Pope Francis and Pope Benedict stress the importance of a method and provide their preachers with helpful direction as to what that preparation method should be.

Both popes emphasize the primacy of prayer — what Dr. Mary Margret Pazdan, OP, identifies as “Contemplo” in a three-step method: Contemplo, Studeo, Praedico. Pope Benedict in Verbum Domini writes that the homily must be prepared through meditation and prayer. He offers three questions for preachers to use in this meditation: “What are the Scriptures saying? What do the Scriptures say to me personally? What should I say to the community in front of me in light of its concrete situation?” Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium underlines this first step in a homiletic method: “The first step after calling on the Holy Spirit is to give full attention to the biblical text — the basis of preaching.” He, too, calls for the preacher to: first discover what the author intended the text to say, then engage in a personal reading, and finally settle upon what the faithful need to hear. The Homiletic Directory recommends Lectio Divina to do these things.

These are overarching principles and approaches. Every preacher will need to find a personal way of accomplishing what the Church wants in the homilies of its preachers. Here is how I have approached the great task of preaching in the name of the Church. I offer it not for imitation, but as a resource to help inform other preachers as they develop their own method.

Step 1: Contemplo

The Homiletic Directory recommends that preachers take advantage of “the constellation of readings and prayers of the celebration.” It advises the preacher to take fully into account not only the lectionary readings, but what is also sometimes called “the Liturgical Bible,” that is, all the prayers and liturgical texts of that Mass. The term constellation is particularly apt. Rather than look at one star, or in this case one reading, the preacher steps back to see that a number of stars make a constellation revealing Orion, or the Big Dipper. So, too, the Homiletic Directory asks the preacher to step back and rather than focus on one reading to find the larger picture that extends through all of them.

My own practice to bring the constellation into focus is to look first at what the Church gives us in the liturgical texts before I look at the lectionary readings. Thus, my first Contemplo is on the Entrance Antiphon, Collection, Gospel Acclamation, Prayer over the Offerings, Communion Antiphon, and Prayer After Communion. This prayerful reading can yield a theme put forth for the whole Mass. It also has meant explicit preaching on these liturgical texts in the homily itself.

The next Contemplo uses Lectio Divina for a prayerful reading of all three readings and the responsorial psalm. Connections with and inspirations around the liturgical texts in the first Contemplo become immediately apparent.

The end of my Contemplo stage is the devising of what Thomas Long in The Witness of Preaching calls a Focus Statement and a Function Statement. The Focus Statement is the message that the preacher settles on which emerges from the readings and applies to the listeners in front of him. The Function Statement articulates what effect that message is meant to have. It is important at this stage to articulate both these statements in short sentence without the use of “and.” The use of “and” or subclauses often indicates more than one message, or a complicated message in several parts. Bishop Untener’s metaphor in Preaching Better of a single pearl, rather than a string of pearls, or Cardinal Newman’s advice in The Idea of a University to aim for a single bull’s eye requires ruthless focusing. As rich as the preacher’s Contemplo might have been, not everything should be included in a single homily as that would overwhelm the listeners.

Step 2: Studeo

Preachers can be tempted to go directly from Contemplo to Praedico — composing and then delivering their text right after receiving insights or inspirations in their Lectio. Studeo is a valuable step of consultation with the whole tradition of the Church both ancient and modern. That consultation helps situate the preacher and his inspirations in that tradition, ensuring that his inspirations, and his Focus and Function statements are indeed consistent with the teachings of the Church. In this way, the homily is the Church’s agenda rather than the preacher’s, thus preventing a personal hobby horse from hijacking the preaching event. Studeo helps him clarify what he is saying by sometimes correcting information, or by providing even better examples or references. In short, it enriches the homily. As with Contemplo, the preacher does not use everything he uncovers, but even what is not directly used becomes a foundation for the homily when he builds its structure.

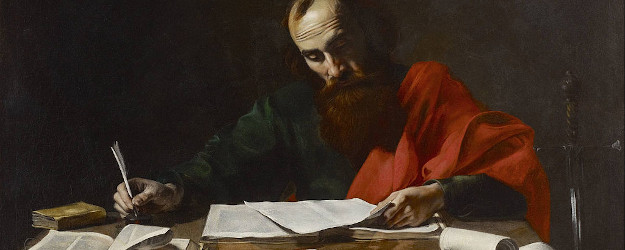

My Studeo involves starting with trusted, reliable sources including biblical commentaries, Church documents, and prominent theologians. It also means checking out credible contemporary cultural and news sources to verify any contemporary references and fill in background. Studeo can be particularly fruitful if the preacher goes beyond print sources. One of the most powerful parts of Studeo for me has been looking at famous paintings of the biblical events or parables in the Mass readings. Just as a commentator gives insight in the writing, so a painter provides insight and provides powerful avenues for preaching in images. Fra Angelico’s painting of The Annunciation is one example. That painting pushes the expulsion from the garden of Eden against the coming of the Archangel Gabriel with God’s plan of reconciliation. The Holy Spirit which fills Our Lady in that painting is sent out at the moment of the expulsion and crosses time by piercing through both events simultaneously. Music is also an important part of Studeo. It may be that the words and background of a hymn like “Amazing Grace” or “Lord, Make Me an Instrument of Your Peace” helps elucidate the Focus Statement. Phrases can be used in the homily, and arrangements made with the choir to sing the hymn at the Offertory which helps extend the impact of the homily as the Mass moves toward the Eucharist.

Step 3: Praedico

After have prayed with the liturgical and lectionary texts, and consulted print, visual, and musical sources, I then sit down to compose and structure the homily. Many avenues are open to the preacher for this. Which one he chooses depends on what he intends to accomplish, and what sits best with his personality and gifts. In my case, most of my preaching works inductively – a method that comes out of the work of Fred Craddock in the New Homiletics. In particular, I have found the work of Eugene Lowry in The Homiletical Plot to be of particular value. That method starts with an upfront identification of a problem that the listeners may have with the reading, what it means, its practicality in their lives, or with a Church teaching founded upon that reading that they might find difficult. The homily then moves through possibilities until it arrives at a clue of resolution found in the other readings, lectionary or liturgical, of that Mass. Essentially, this method articulates the listeners’ questions and takes them on the journey that the preacher went on as he prepared the homily until he found the key to the mutually revelatory readings just heard. It is not that the preacher needs to then come up with a pat answer to everything, but he does explore how that hint, that key to the problem, unfolds the difficulty and has implications for daily life.

My preaching practice is to preach without notes. I have found that extraordinarily liberating. It has kept my preaching focused to what I can remember, more oral than academic text, and concretely visual rather than abstract. Although I do not preach from a text, my Praedico does involve fully writing out the text so that I have the experience of finding all the words I need with a sense of how much time the homily requires. Having done that, however, I do not bring the text with me to the ambo.

The next step in Praedico for me is to find a way to keep the homily fresh in my mind. I do not memorize the homily as rather than being word perfect, my intention is to be idea perfect – that is, to move from idea to idea, or what David Buttrick in Homiletic Moves and Structures calls “moves.” The way that works for me is to use the “Memory Palace system.” Attributed to the Greek poet Simonides, and taught by Fr. Matteo Ricci in 16th-century China, the Memory Palace makes use of the ability to remember places more clearly than abstract ideas. Choosing a familiar place, like one’s own home for example, the preacher pegs a move or section of his homily to a particular part of that place, like the doormat, or a hall table. When this is done, the preacher need only in his mind walk through the place he has chosen retrieving the concepts he has put down in the order that he wants to present them.

This method from Contemplo to Praedico informed by the writings of the various preachers mentioned throughout this article has been useful in my own practice to mine Scripture, apply them to the listeners, and deliver the message in a coherent manner. Each preacher naturally finds his own path, but as St. Francis de Sales and our recent popes insist, it is important to have a method. Preaching is the primary apostolate and the people in the pews are right to expect the best we can offer. Method helps us to give them our best.

Very insightful

“Pope Benedict in Dei Verbum writes that the homily must be prepared through meditation and prayer…… ”

I think the correct document is Verbum Domini not Dei Verbum which is a document of Vatican II. Thanks

Thanks for pointing out the oversight! Fixed now.

Most of the Protestant ministers/pastors I have known spend three to four hours or more writing their sermons and another two to three hours practicing its delivery. I find most Catholic priests have a small piece of paper in their hands or just wing it. The quality shows through.