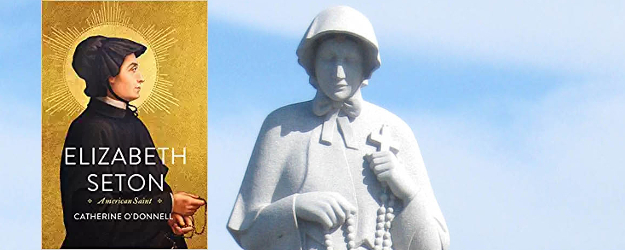

O’Donnell, Catherine. Elizabeth Seton: American Saint. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018. 508 pages.

As the only scholarly biography of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton to be published since her canonization in 1975, Christine O’Donnell’s work is a notable contribution to the historiography surrounding the first native-born American saint. Much important archival work has been done since the last such biography of Mother Seton was published 60 years ago and these efforts have borne fruit in O’Donnell’s book. She has done extensive research in all the relevant archives so that the impressions of the relatives and friends of Elizabeth Seton have depth that previous biographers were unable to provide. Particularly noteworthy in this regard is her portrayal of Elizabeth’s father, Richard Bayley, who was so influential on her development. As a doctor and scientist in late eighteenth-century New York, her father is a historic figure in his own right. Likewise, O’Donnell’s use of Elizabeth’s children’s letters to their mother provide an important perspective on their mutual relations.

Another contribution of O’Donnell’s work to the existing scholarship on Mother Seton is her contextualization of her subject’s life within the history of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. O’Donnell provides a good summary of the national and international environment that shape the advance of Seton’s life and her founding of the Sisters of Charity in America.

However, while O’Donnell’s book builds on the work of previous biographers, most notably Annabelle Melville and Joseph Dirvin, it cannot displace it. The earlier works more effectively conveyed a sense of St. Elizabeth’s spirituality. For a historical figure who is remembered primarily for being a saint, this is the most important part of her biography. To her credit, O’Donnell has candidly volunteered in an essay she published on the internet following the release of the book that she “shied away” from writing about Elizabeth’s faith life.1

Her sense of inadequacy in exploring what she recognizes was “the wellspring” of Elizabeth’s life perhaps explains O’Donnell’s missteps in this area. She sometimes fastens on to certain moments of Elizabeth’s evolving love affair with God as defining the relationship as a whole. As with most mystics, and true lovers of every sort, St. Elizabeth’s relationship with God was tempestuous, passionate, ecstatic, and painful — sometimes all at once.

Granted it is not an easy thing to comprehend, but O’Donnell seems unfamiliar with the paradoxes of true holiness. The more one experiences God’s love, the more one is horrified by sinfulness, especially one’s own. Additionally, those with the type of uninhibited love for God that Elizabeth had experience profound suffering at the thought that they are in any way resistant to His will. Saints who reach this level of intimacy with God write of experiences of rapture and desolation following in quick succession. Like Jesus Himself, they can cry out “my God my God, why have you forsaken me?” in one breath and “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” with the next. Lacking this understanding, O’Donnell states on page 416 that at one point Elizabeth “thought she might be destined for hell.” However, if one reads the whole quote that O’Donnell cites, and not her edited version, it is clear that Elizabeth in her self-effacing and even humorous way, is actually praising God for the wonders of his love. The quotation O’Donnell cites is from a letter she wrote to her spiritual director and friend, Father Simon Gabriel Brute, in the year before she died. Father Brute went by his middle name and Elizabeth referred to him simply as “G” in her letters.

G, ‘blessed’ mind not my follies, I see the everlasting hills so near, and the door of my Eternity so wide open that I turn too wild sometimes. Oh, if all goes well for me, what will I not do for you – you will see – but alas – yet if I am not one of his Elect is only I to be blamed, and when going down I must still lift the hands to the very last look in praise and gratitude for what he has done to save – What more could he have done – that thought stops all.

There are other instances where O’Donnell’s use of truncated quotes results in a misrepresentation of what Elizabeth actually wrote. For example, in her version of the death of Elizabeth’s youngest daughter, Rebecca, O’Donnell leaves out important elements of the original account which would provide the reader with a fuller perspective of what actually transpired between mother and daughter during the latter’s last days.

In other passages O’Donnell implies that Elizabeth was insensitive to the physical suffering of both of them, Rebecca and her oldest daughter, Anna, as they were dying from tuberculosis. Elizabeth writings indicate that she firmly believed that suffering is salvific when united with that of Christ. So, while doing her best to alleviate her daughters’ suffering, she urged them to entrust themselves to God’s will in the midst of their pain. In fact, Elizabeth kept a detailed journal of her daughters’ last painful days because she believed in the witness value of Anna’s and Rebecca’s faithfulness in the midst of their suffering. Elizabeth trusted in the words of St. Paul, that “all things work for good for those who love God,” and was encouraging her daughters to trust in God’s love. Elizabeth believed that if we surrender to the current of God’s will rather than swimming against it, it will propel us forward to the ultimate happiness of union with him. When Elizabeth urged Rebecca to pray “Thy will be done,” she wasn’t, as O’Donnell asserts, reminding Rebecca of “her duty.” Rather, she was urging Rebecca to trust in the teachings of Jesus, and to lose her life in God’s will so that she might find it for eternity.

O’Donnell’s unfamiliarity with these elements of the Catholic spiritual tradition may explain her misinterpretations in these areas. However, her self-confidence when it comes to reading Elizabeth’s mind is harder to excuse. To subscribe to O’Donnell’s confident omniscience would mean accepting among other things that: Elizabeth deluded herself and misled others in regard to her family’s rejection of her conversion to Catholicism, at one time she wanted to leave the United States because she was convinced “she was ill-suited to live amid its diversity and tolerance,” and that she dissembled (lied?) to her son and to her best friend. It would be one thing if O’Donnell makes these remarks as conjectures. After all, no one, least of all, Elizabeth herself, has ever claimed that she was sinless. However, O’Donnell presents these assertions as facts.

In recent historiography, there has been a reappraisal of the role of slavery in the history of our nation and of the Catholic Church in America. Evidently wishing to keep pace with this reappraisal, O’Donnell was on the lookout for any connection between Elizabeth Seton and slavery, however tangential. In her Internet essay O’Donnell wrote, “As I looked through letters and journals, I got a sense of Seton’s intellectual curiosity, glimpsed the way the era of revolutions affected her choices, and realized that slavery would be a part of this story, as it is a part of all stories of early America.” One wonders what exactly O’Donnell “realized” about slavery being part of the Seton story if O’Donnell has already decided “it is a part of all stories of early America.” Rather than being a matter of discovery, it seems that O’Donnell was determined to inject the issue of slavery into her narrative. In any case, O’Donnell paints with a broad brush. On page 386 O’Donnell writes:

Elizabeth makes few mentions of the institutions slaves’, except to note Joe’s kindness to the crippled Bec and, once, to mention her responsibility to catechize the “good blacks”: “Excelentisimo!” she wrote, her tone indecipherable. The slim record of engagement offers its own evidence. Elizabeth had a gift for making others feel loved and seen, known in their human specifics. She did not often turn that gift toward the people of color who labored for the sisterhood, and when occasionally she did, she did so in a way that did not acknowledge the central, brutal fact of enslaved people’s lives.

It is true that the Sulpician clerics who had oversight of Elizabeth’s Sisters of Charity did have slaves. It is also true that some of the families that sent their daughters to Elizabeth’s school in Emmitsburg owned slaves. According to O’Donnell, since Elizabeth never wrote about the evils of slavery she is implicated in the crime. In the excerpt cited above, O’Donnell, relying once again on her omniscience, asserts that Elizabeth was not only indifferent about slavery but also lacking in charity toward the slaves that she encountered. Historians are supposed to deal in facts and their surmises should be supported by data. O’Donnell’s judgments regarding Elizabeth’s attitudes towards slavery and slaves are unsupported by the documentation and unfair. The facts are that Elizabeth Seton and her Sisters did not own any slaves themselves. Nor do her extant writings say anything about her thoughts on the institution of slavery. It is also a fact that O’Donnell has no way of knowing how “often” Elizabeth engaged with slaves or turned her “gift for making others feel loved and seen” toward them. And, without any documentation to the contrary, it should be safe to assume that Elizabeth showed the slaves she encountered the same compassion that she showed to others.

In summary, Catherine O’Donnell has written a valuable biography of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton. She has much to say which is of interest when she sticks to what is actually knowable.

- Catherine O’Donnell, “Elizabeth Seton and Me: Or, How I Almost Wrote a Book about a Saint Without Mentioning God,” The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, https://earlyamericanists.com/2018/09/07/guest-post-elizabeth-seton-and-me-or-how-i-almost-wrote-a-book-about-a-saint-without-mentioning-god/. ↩

I appreciate Fr. Conley acknowledging the historical significance of Catherine O’Donnell’s 2018 biography of Elizabeth Bayley Seton although I do not share the intensity of his critique. O’Donnell, an historian of the Colonial Era of the new republic, has enriched readers with a better understanding of the petite woman, Episcopalian wife, mother, and widow who became Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton. Elizabeth lived her life as a woman who overcame adversity, fulfilled her primary vocation as a mother, and realized God’s plan for her as a woman of faith. Seton’s path to holiness meandered through the sociocultural context of the society of her day.

Other authors have examined aspects of Seton spirituality. For example, Joseph Dirvin’s, “Soul of Elizabeth Seton;” Shinja Lee, SC, Elizabeth Seton and Spiritual Direction;” Annabelle Melville’s Introduction to Melville and Ellin Kelly, “Selected Writings Elizabeth Seton.” O’Donnell’s excellent biography makes an invaluable contribution to Seton scholarship.

There will always be additional areas for research and study. There are other lens through which students may view the Bayley-Seton story and her legacy. The corpus of Seton papers are published, R. Bechtle, SC & J. Metz, SC, Collected Writings of Elizabeth Bayley Seton, 3 vols. (New City Press). I commend O’Donnell for offering new insights about Betsy Bayley of New York, and for highlighting Mother Seton as a spiritual formator and leader. Elizabeth considered that being brought into the Catholic Church was one of the greatest blessings bestowed on her by God. In the spirit of this holy American woman, Catherine O’Donnell corresponded nobly to her “grace of the moment” in producing this biography. I believe that Saint Elizabeth Seton would muse that “God will provide” for others to continue to explore Elizabeth’s relationship with God and how she inculturated the Vincentian charism as the pathway for her Sisters of Charity.