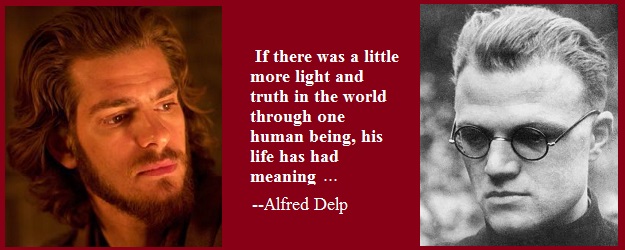

Andrew Garfield plays a fictitious Jesuit missionary, Sebastian Rodrigues, in the new movie Silence. Photo of Fr. Alfred Delp, S.J., who died for his faith in Germany in 1945.

What ultimately makes a Christian martyr—an individual’s heroism or the grace of God? Martyrdom is a radical call to assume the form of Christ’s self-sacrifice on the Cross for the sake of others, however the martyr’s vocation neither consists of him speaking of and for himself, nor his standing by his own strength. For Fr. Alfred Delp, S.J.,1 martyred in 1945 because he took part in an anti-Nazi resistance group and refused to renounce his priesthood, the grace of Christ’s self-giving as it unfolded in his life took precedence over any agenda that he might have held. In his testament “After the Verdict,” composed in the days between his sentencing and execution, Delp wrote,

What is God’s purpose in all of this? … But one thing is gradually becoming clear—I must surrender myself completely. This is seed time, not harvest. God sows the seed and sometime or another he will do the reaping. The one thing I must do is to make sure the seed falls on fertile ground. I must arm myself against the pain and depression that sometimes almost defeats me. If this is the way God has chosen—and everything indicates that it is—then I must willingly, and without rancor, make it my way. May others at some future time find it possible to have a better and happier life because we died in this hour of trial. I ask my friends not to mourn, but to pray for me, and help me as long as I need help. And to be quite clear in their own minds that I was sacrificed, not conquered.2

Within the spiritual framework of Delp’s martyrdom, one can grapple with the dilemma of the fictional Fr. Sebastian Rodrigues, S.J., who renounces his faith in Martin Scorsese’s film adaptation of Shusako Endo’s novel, Silence.3 The novel and the film put the faith of Rodrigues on trial, inviting the audience to empathize with a priest whose zealous faith reaches a breaking point under duress so as to understand what apostasy might look like in a certain context. Rodrigues came to Japan ready to die for his faith, but ends up renouncing it, however, Scorsese does not glorify the apostasy but portrays it as a tragedy, serving to point to a deeper truth. With the helpful contrast of Delp’s witness, the tragedy of Rodrigues reveals that martyrdom is not a matter of our heroism, our attaining self-mastery through the perfection of our deeds, but rather is a matter of allowing Christ to become our Master in our weakness and in and through our openness to Him.

Alfred Delp: Openness to God

Delp’s openness to God is a process that occurs in incremental steps. A significant period that marks Delp’s awareness of the need to be open to God’s guidance, recognizing the importance of prayer and encountering the transformative love of God, was making the Spiritual Exercises during his tertianship4 in October 1938. A significant theme in his journal is his devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus: six of the journal entries make serious references to this devotional practice.5 Delp regarded the Sacred Heart devotion not as a simple form of piety but as central to Christian life because it allows Christians to encounter the figure of Christ. Delp situates devotion to the Heart of Jesus within the context of prayer, showing that a proper understanding of the devotion applies the spiritual sense of hearing—implying that prayer consists of a dialogue between God and the creature, consisting of God’s initiative and the believer’s obedient heart. According to Delp, obedience to Christ opens and enlarges the human heart, and the resulting closeness to the Lord enables people to give themselves to others. The true person “is a Lover. Only he is the full man.”6 At the same time, Delp acknowledges his egoism and lack of love in his life: “I am so poor and small and nothing because I have loved so little. I must let go of myself and give myself away. A large heart for God and [His] people—an open heart to surrender, serve, give away, sacrifice.”7 This call to self-sacrificial love deepens for Delp as he ministers to people during the Second World War, and as he approaches his death. The kind of prayer that Delp describes in his tertianship entails an encounter with God in Christ, and a profound listening to what God says. Persons are relational beings; their most crucial relationship is with Christ. This response entails surrendering to God and giving oneself away in love, as Delp indicates in his retreat diary.

Everything is based on Divine mercy. You will lead me, I must listen to You. He will lead me, I must trust in You. Life ceases being a lonesome and laborious monologue, it becomes a dialogue, it becomes more like: Cor ad Cor loquitor.8

Here, this life of interior knowledge of and obedience to Christ rooted in the love of Christ brings Delp to a martyrdom of indifference—a radical availability to be led and sustained by Christ. Such a personal relationship with Christ will enable Delp to persevere in the tribulations of imprisonment. The most poignant treatment of the devotion occurs in a journal entry dated 1 November 1938—a few days before the end of the retreat. The devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is described as a spiritual practice that involves the Trinity and self-sacrificing service. Delp writes:

I must live intimately with my God; I to you; intimacy; and have joy in Him and meet Him with the heart…The Heart of Jesus is the way of sacrifice, of fidelity, of passion; His Heart leads me to the Father. Only the Lover can be the true man. Everything else is a sham and a fraud. In the Kingdom of God, there is no self-made man. An open heart [receives] the thoughts of God. An open ear [receives] his guidance. Life either comes to grips with the great Heart or nothing else. 9

Here, Delp acknowledges that authentic knowledge of God and the human self emerges from a conscious intimacy with Jesus Christ, who is the bridge between God and the human person, and, as such, is the perfect realization of human existence. Furthermore, persons should look to Jesus for their fulfillment, because the dynamic of discipleship becomes possible only in relationship with Christ, who enables the person to lead a life of self-sacrifice.

The Heart of Jesus devotion helped Delp to recognize that following Christ engages all of a person’s abilities, and draws them into Christ’s work of redemption. This openness will require allowing God’s grace to build upon human nature, challenging any un-freedom, and instilling a disposition of selflessness:

I must get away from myself—and learn how to serve and sacrifice. I am a great egoist . . . Love learns with Jesus Christ on the way of the Cross. A person pays attention because God loves him . . . I have been created and called to love God, to serve God, for joy in God.10

For Delp, a person cannot find or establish his own purpose in life; it is only in intimacy with Christ that a person can understand the meaning of his existence. He reaffirms this experience in the following day’s journal entry: “The Heart of Jesus is the way of sacrifice, faithfulness to the Trinity, to the Father. The Cross is the way of the Heart of Jesus.”11

The Hubris of Sebastian Rodrigues

The protagonist of Silence is the presumptuous young Jesuit priest Sebastian Rodrigues, who undertakes a furtive mission to Japan to find out if his former teacher, Jesuit Father Ferreira, truly committed apostasy. On the surface, Rodrigues embodies a passionate faith; he is self-assured and optimistic about his capacity to endure physical and mental suffering for his assignment. From the start, it is evident that Rodrigues evinces a heroic priesthood, representing the best of the Jesuits. Rodrigues’ confident view of himself and faith starts to unravel once he arrives in the swamp of Japan, his mission being fraught with complications. These difficulties are discernible from Rodrigues’ first interactions with the Japanese Christians—he pities them, describing them as “ignorant peasants.” Rodrigues is particularly annoyed by a vagrant named Kichijiro, an apostate Christian, who watched his family die, and is now clinging to the young Jesuit priest. The doddering, pathetic, and shameful Kichijiro plays the foil to the heroic Rodrigues.

At first, Rodrigues considers Kichijiro no more than a Judas figure. As the young Jesuit and Kichijiro are traveling through the mountains, Rodrigues says:

Men are born in two categories: the strong and the weak, the saints and the commonplace, the heroes and those who respect them. In time of persecution the strong are burnt in the flames and drowned in the sea; but the weak, like Kichijiro, lead a vagabond life in the mountains.12

However, these categories founded on Rodrigues’ hubris gradually break down in the face of the persecution of the innocence, and of his own trial before the Japanese inquisition. Kichijiro plants seeds of doubt in Rodrigues’ seemingly firm faith—by inquiring “why has Our Lord imposed this torture and this persecution on poor Japanese peasants? Father, what evil have we done?”13

Rodrigues’ faith is consistently tested and tried, and well before the end of the story, it is on the verge of collapsing altogether. He watches from his hiding place as two Japanese Christians are tied to stakes on the beach, where the incoming tide wears down their resistance, and they eventually die, days later, of exhaustion. Rodrigues stares at the sea and perceives God’s aloof face in it:

The sound of those waves that echoed in the dark like a muffled drum; the sound of those waves all night long, as they broke meaninglessly, receded, and then broke again on the shore. This was the sea that relentlessly washed the dead bodies of Mokichi and Ichizo, the sea that swallowed them up, the sea that, after their death, stretched out endlessly with unchanging expressions. And like the sea God was silent.14

The persecution undermines Rodrigues’ optimistic view of himself, his faith, and his apparent understanding of God:

We did not make that long journey around Africa, across the Indian Ocean, on to Macao and then to Japan just to flee from one hiding place to another. It was not to hide in the mountains like fieldmice, to receive a lump of food from destitute peasants and to be confined in a charcoal hut without being able to meet Christians. What had happened to our glorious dream?15

The Japanese inquisitor forces Rodrigues to listen to the cries of the Japanese peasants, who converted to Christianity, being tortured. As he witnesses the peasants singing about entering into paradise, Rodrigues finds himself again visualizing the silence of God, “the feeling that while men raise their voices in anguish, God remains with folded arms, silent.”16 He is beset with a quandary that he had not prepared for: “He had come to this country to lay down his life for other men, but instead of that the Japanese were laying down their lives for him.”17 The young Jesuit priest had aspired to his own martyrdom; he even anticipated his own Gethsemane.

Rodrigues’ view of martyrdom and suffering changes vastly throughout the story, and in a similar yet converse way, he moves from a heroic figure to that same picture of humanity that Kichijiro represents. When Rodrigues’ former companion, Father Garrpe, drowns after his refusing to renounce Christianity, and his trying to save the Japanese Christians being thrown into the sea, Rodrigues begins to be engulfed by his own pity. He sees himself as “the most weak-willed” and undeserving “of the name ‘father.’”18 The broken young Jesuit priest displays the state of fallen man: “His pity for the [Japanese Christians] had been overwhelming; but pity was not action. It was not love. Pity, like passion, was no more than an instinct.”19 Tragically, Father Rodrigues’ condescending remarks about “ignorant peasants” and the “weak” and “common” Kichijiro come crashing down on him. Rodrigues’ desire to follow Christ is deliberate. On the other hand, the desire to seek martyrdom can become a monstrous idol, a desire for heroism that devolves into an image of God as an aloof, cold tyrant. Rodrigues’ subtle pride had seduced him into seeking a vocation that did not belong to him.

Discipleship: Receptivity and Weakness

Both Delp and Rodrigues recognize that the Christian life involves a search for God, so that they may give their lives to God and others. However, it was Delp who recognized early in his priesthood that the search for God begins with him already having been found by Christ in his weakness. Delp returns to this spiritual insight six years later, in the Fall and Winter of 1944-45, in his confinement as a political prisoner in Berlin’s Tegel Prison.

Before his trial and sentencing, Delp wrote from prison a series of meditations on the mysteries of the Christian faith. His first two devotions were on the devotion to the Heart of Jesus, written in late Fall 1944. The starting point of Delp’s prison meditations on the Sacred Heart is the self-humbling of Christ, which includes His offer of friendship to human persons, which restores the relationship between God and humankind. Delp begins by stating that the devotion communicates the offer of “friendship with the Lord to a collection of like-minded, frail hearts and souls dedicated to Him,”20 describing Jesus’ friendship as a response to the “scream and forsakenness of the people” and “an offer of mercy from God to save a threatened humankind.”21 Writing from his cell, he shows that the devotion to the Pierced Heart entails a love that descends into forlornness and rescues weak persons:

The person needs to know that a Heart is beating here which can do more than the little or the many things which a human heart is capable of. O, the Heart of God is quite powerful. It overcomes distance. It climbs over walls. It breaks through loneliness. It redeems forlornness that nobody else has the courage to address.22

Jesus’ giving up of self for the world’s salvation is understood as the humbling of Divine love for the sake of humanity. For Delp, his dehumanization by the Nazis is matched by an address from God:

This devotion concerns a relationship of intimacy between Christ and me. By grace, words are said back and forth and a genuine supreme love flows from the core of the heart of humankind and encounters the Heart of God in order to discover there everything: call, awakening, and the capacity to stay en route until home. All this is the merciful and creative call of the Divine Heart of Jesus.23

The conversation between Christ’s Heart and the human person’s heart is understood as a saving event, occurring as an interior reality between God and Delp. That is, the heart represents what is innermost, genuine, and precious in Delp, and the Sacred Heart is, likewise, the intimate center of God. It is here that the opening up to God, and to human persons, occurs. Such opening, according to Delp, suggests the depth of an existence which does not fall under man’s mastery or autonomy.

The encounter between Christ and the believer lies at the heart of Delp’s reflection on the Sacred Heart devotion, involving the Divine initiative and an obedient listening. The Sacred Heart devotion ultimately is a liberating dialogue between God and the person, allowing the Lord to transform the human being into a Christlike servant of others. Delp states:

The appeal to the personal individual is two-fold: for [the individual’s] salvation and healing and inner transformation into the likeness of Christ [and] into the willingness and ability to become an effective and fruitful instrument of the Lord’s redemptive-salvation.24

In Delp’s view, the devotion reminds people that God is encountered not in abstract thought, but in the person of Jesus Christ, whose gift of loving friendship with Christ entails accepting the call by God to interpret the love of the Cross to a broken world, not only in what can be said, but in what can be lived out.

A Christian exists as one who has been given an identity by virtue of the redemption of Christ. The healing entails permitting Christ’s saving love to address the human person at the core of his existence; and because Christ has entered into complete solidarity with sinful humankind, God takes up a concern for all aspects of our lives, including those that are weak. Christ, thus, transforms the human person, one so unfit for speech, into a dialogue partner with God.25 Delp’s meditation on his experience in prison reflects this theology of becoming attuned to God through prayer. He writes at the start of his second prison meditation on the Heart of Jesus that:

Between heaven and earth, there is no great chaos and, also, no great silence, or a sort of generous neutrality, but rather that living relationship which goes back and forth—from this truth prayer, adoration, and religion live, and I have utterly and completely lived from it during the last few weeks. Moreover, it should remain that way.26

Here, Delp acknowledges that his following after Jesus proceeds from his encounter with, and transformation by, Christ. The devotion to the Heart of Jesus assists Delp because the merciful love of God, in Christ, encounters Delp in his sufferings, and transforms the sufferings into prayer, into a dialogue with God in the midst of forsakenness.

The problem with Sebastian Rodrigues is his hubris, which leads him to a deeper sin—apostasy. The Christian life had been for him, before the apostasy, a path to accomplishing heroic deeds, but he lacks real poverty in his heart, where authentic, spiritual hearing is possible. This poverty is understood as a receptive silence, allowing the person to hear the call of Christ. This silent receptivity, an integral dimension of deep prayer, involves the believer’s entrusting himself to God, and allowing God himself to form him. If the Heart of Christ is permitted to transform the human heart, then it is a heart open to God, allowing God to heal and to lead. This silence is thus not an absence of words or a mere emptiness.

A silent, listening heart, open to God’s guidance, needs the mark of indifference. Indifference is not a stoic spiritual aloofness, but rather has the character of being willing to be led by God into various human conditions as God wills. Both Delp and Rodrigues desire the saintly life, which can include the life of the martyr, however Delp understands that the saintly life is neither an attempt to become a hero, nor to expand one’s talents, nor is it a path to destroy oneself. As Delp reflected, “God does not need great pathos or great works. He needs greatness of hearts,”27 so the way of holiness entails a surrender of self to God.

With Delp in mind, one can see the tragedy surrounding Rodrigues. His desire to be a martyr was a mistake because it was what God required of him. His striving to seek his “glorious martyrdom” was an act of ego, a monologue, not a dialogue between God and him. As a consequence, in the end, it led to him facing the most difficult decision possible. He would have gladly accepted martyrdom, but that was not what was put before him. To save the persecuted Christians, he had to renounce his faith, an act of martyrdom worst than death, and given that there were no other priests available to him, he committed a grave sin from which he could not get absolution. It was Rodrigues’ ego that pushed him into such a situation, his initial sin that led to the graver sin.

Moreover, Rodrigues does not answer Kichijiro’s questions. He regards Kichijiro as not even worthy of being called evil, at least in comparison to the cunning and ruthless evil of his Japanese tormentors. The place for the weak man is right there in the sacrament of reconciliation, but Rodrigues is incapable of seeing it. As saints and spiritual masters have consistently pointed out, the Christian life is at its base the constant battle between humility and hubris. Weakness in this context is not generic human weakness but related to Christ, who “was crucified in weakness” (2 Cor 13:4), whose “power is perfected in weakness” (2 Cor 12:9).28 For Christians, human weakness “provides the best opportunity for divine power”29 to save humankind. The world tries to overcome weakness, whereas God uses weakness for the work of redemption. Kichijiro’s weakness is the perfect foil to Rodrigues’ fortitude, but Kichijiro’s weakness is also his avenue toward humility, whereas Rodrigues, with his narcissistic and facile identification of himself and his own circumstances with Christ, is undone ultimately by his pride. When Rodrigues falls, we do not see him seek out the sacrament of reconciliation, as Kichijiro does, time and time again.

So, do we find such a pattern of humility and self-surrender in the Christian journey? Such a pattern is arguably first encountered in Delp’s life during the month-long Spiritual Exercises during his Tertianship in 1938. In this retreat, we saw Delp acknowledging his egoistic ways during the healing and transformative encounter with Jesus Christ. Delp expressed the desire to give his life to Christ, and to serve others, but it could not be on his own terms: Delp risked his life to be part of an underground network that assisted the escape of persecuted peoples; Delp then participated in planning for a postwar Germany based on Catholic social teaching with members of the Kreisau Circle. Such service does not speak of heroism or gallantry in a struggle to bring forth the Kingdom of God, but rather of a radical availability to do God’s will. Delp’s imprisonment was the schooling, or deepening, of that self-surrender to God. In prison, Delp makes no claim of saintliness, but speaks of the transformative love of God, and of his friendship in Christ with members of the Kreisau Circle. Delp does not attempt to ignore his creaturely identity, but exposes his finitude to the merciful love of God.

Conclusion: Self-Surrender

Both the historical Delp, and the fictional Rodrigues, desire to do God’s work and, no doubt, they are convinced of the righteousness of their work. Both Delp and Rodrigues, as prisoners, doubt God’s providence, and recognize that they are paralyzed, and made small. Delp, however, was able to draw from his tertianship experience and re-encounter the gift of God’s love in the Sacred Heart devotion, which allowed Delp to live from God’s freedom, and not his own.

Two prayers associated with Ignatius of Loyola can help to elucidate the interiority of both men. The first is the prayer for generosity,30 which is full of eager passion. The subject of the verbs is the human subject, and there is a touch of heroism, the superhero wading into battle, invincible and heedless of wounds.31 This prayer marks the spirituality of the young Rodrigues, who is at the start of his priestly vocation. Delp, however, came to understand that the Christian life did not rest on his heroic achievements. The months of imprisonment became an occasion for a profound surrender of self, and a fruitful silence, as opposed to an empty silence. Tegel Prison was an opportunity to encounter God in Christ, not in some supra-sensible oasis kept free from a broken world, but rather in the wreck of human existence. Towards the end of his imprisonment he wrote:

Mass in the evening was full of grace … I didn’t sleep much last night. For a long time, I sat before the Host, and just kept praying the Suscipe.32 In all the variations that applied to me in this situation.33

Here, the Ignatian pilgrim, praying the second prayer, the Suscipe, has come a long way, and understood what discipleship is.34 The subject of most of the verbs is God, by whose love alone, we can become what we are meant to be, and do the impossible. For Delp, what made discipleship possible was not heroism, but intimacy with Jesus, who embraces the frailty of the one who calls him. Through his experience, Delp came to recognize the simple truth that the disciple must surrender his entire being so that he might become an instrument in Christ’s work of redemption; only through his experience and acceptance of weakness does the Christian come to hear the true call of Christ.

- Alfred Delp joined the Jesuits in 1926, was ordained in 1937, and pronounced Final Vows in Tegel Prison in late 1944 before his trial and execution. At the outbreak of the war, he participated in a clandestine network to help Jewish people escape to Switzerland from Munich. In 1942, Delp’s Jesuit superior sent him on mission to work with the Kreisau Circle, a group of German intellectuals from different societal backgrounds planning for a post-Nazi Germany based on Catholic Social Teaching. Although the Kreisau Circle had nothing to do with Operation Valkyrie, Delp was arrested with other members of the group after the attempted assassination of Hitler in 1944. After several months of imprisonment and torture, Delp was brought to trial. He was offered his freedom if he would renounce his priesthood. Delp refused and was hanged on February 2, 1945. ↩

- Alfred Delp, The Prison Meditations of Father Delp (New York: MacMillian Company, 1963), 163-64. ↩

- This article will draw from both the novel and the film Silence, making distinctions when necessary. ↩

- Tertianship usually occurs several years after ordination. It is the Jesuit’s final year of formation before formal entry into the order. During this stage, which has been called “the school of the heart,” a Jesuit undertakes the full thirty-day Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola for the second time in his life. For Delp, the Spiritual Exercises provided a period of intense personal prayer, and he kept a journal of his experience of prayer on the retreat. ↩

- Alfred Delp, Gesammelten Schriften: Geistliche Schriften, ed. Roman Bleistein, vol. 1 (Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Josef Knecht, 1982), 256-260. ↩

- Delp, Gesammelte Schriften: Geistliche Schriften, 1:259 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 1:257. ↩

- Ibid., 1:257-58. ↩

- Ibid., 1: 259-60. ↩

- Shūsaku Endō, Silence (New York: Taplinger Pub. Co., 1980), 77–78. ↩

- Ibid., 55. ↩

- Ibid., 68. ↩

- Balthasar, Theo-Drama II, 72. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 133. ↩

- Ibid., 134. ↩

- Ibid., 86. ↩

- Delp, Gesammalte Schriften: Aus dem Gefängnis, ed. Roman Bleistein, vol. 4 (Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Josef Knecht, 1984) 243. ↩

- Ibid., 4:243. ↩

- Ibid., 4:258. ↩

- Ibid., 4:249-250. ↩

- Ibid., 4:243. ↩

- Balthasar, Theo-Drama II, 72. ↩

- Delp, Gesammalte Schriften: Aus dem Gefängnis, 4:250. ↩

- Alfred Delp, Advent of the Heart: Seasonal Sermons and Prison Writings, 1941-1944, ed. Roman Bleistein, trans. Benediktinerinnen-Abtei St. Walburg Eichstätt (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006), 82. ↩

- David Alan Black, “Paulus Infirmus: The Pauline Concept of Weakness” in Grace Theological Journal 5.1 (1984) 77-93. ↩

- Ibid., 86. ↩

- Lord Jesus, teach me to be generous; teach me to serve you as you deserve, to give and not to count the cost, to fight and not to heed the wounds, to toil and not to seek for rest, to labor and not to seek reward, except that of knowing that I do your will. Amen. ↩

- Gemma Simmonds, “The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola and Their Contributions to a Theology of Vocation,” in The Disciples’ Call (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 93. ↩

- “Take Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and my entire will, all that I have to possess. You have given all to me. To you, Lord, I return it. All is yours, dispose of it wholly according to your will. Give me your love and your grace, for this is sufficient for me.” ↩

- Mary Frances Coady, With Bound Hands: A Jesuit in Nazi Germany (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2003), 115. ↩

- Gemma Simmonds, “The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola and Their Contributions to a Theology of Vocation,” 93. ↩

Recent Comments