Two fundamental principles run through the famous passage from Pope Paul VI’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudium et Spes (24:3), which reads, “This likeness {between the union of the Divine Persons, and the unity of God’s sons in truth and charity} reveals that man, who is the only creature on earth which God willed for itself, cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself.”1 These principles are that “God wills human beings for their own sake, for their good” and “persons can only find themselves in a sincere gift of self.”2 In all the works of Pope John Paul II, from his doctoral dissertation, Faith according to St. John of the Cross (1948), to his last encyclical, Ecclesiade Eucharistia (2003), the gift of self “runs like a deeply embedded watermark.”3

This central theme, the gift of self, begins for John Paul II with the spirituality of St. John of the Cross that was introduced to him by one of his spiritual fathers, a layman named Jan Tyranowski. In 1939, amidst the German blitzkrieg, and the pain of family loss, arose a light in the form of this layman.4 He introduced John Paul II to a deep understanding of human love, and how it is an icon of the Trinity which is the archetype of love. A synopsis of this key understanding can be found in what is referred to as the “Sanjuanist Triangle.” The characteristics of this triangle are:

(1) Love implies a cycle of mutual giving, supremely the gift of self. (2) The paradigmatic instance of such self-gift in human experience is the spousal relation between man and woman. (3) The Trinity is the archetype of such love and gift from which the love between God and human persons, as well as love between human beings, derives as an imitation and participation.5

“The new evangelization is a gift of self before all else. The new evangelization takes up all that Catholics are familiar with, and allows them to discover the gift of self that Jesus makes upon the cross as a kenosis of love.”6 The language of the diocesan priest in the New Evangelization is his embodied gift of self. In the priesthood, a man “fully find{s} himself” through his “sincere gift of self.” The priest is not simply a witness in the sense of providing a role model, as important as that is, of virtue and right action, in the same way that “the cross is not {a} mere example of love; {but} rather, ‘the mystery leaves its efficacious mark.’”7 The priest does not simply make a proclamation of the Gospel, as a sign which points to something else, but in the sacramentality of his very body, through his embodied gift of self, Christ is made present. In this embodied gift of self, the priest is revealed as obedient son, chaste spouse, and spiritual father.

At first glance, evangelization, the New Evangelization, and the Theology of the Body may appear to be three separate topics with no unifying factor. They are united, however, in the person of John Paul II. He is the one common thread that weaves these three together. More specifically, they all coalesce in one man, who offered himself as an embodied gift as diocesan priest ordained on November 1, 1946, for the archdiocese of Krakow in Poland. By offering his gift of self, John Paul II evangelized in, and through, his body. He entered fully into the paschal mysteries of Christ, where, as an obedient son, he embodied the mission of the Son into the world for its salvation. This obedience is not simply psychological, as in doing what one is told, it is an embodied virtue, where the whole body listens to the mysteries of Christ, and those mysteries move that body in mission.

Obedient Son

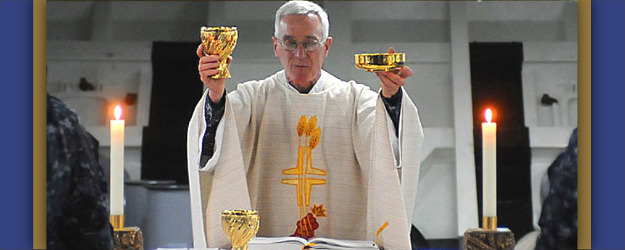

Through the sacrament of holy orders, the priest is the embodiment of Jesus, the divine Son. The priest, in his body, stands in persona Christi capitis, in the person of Christ, the head. At the Eucharist, the priest presents bread and wine and says, “Take this all of you … for this is my Body” and “for this is the chalice of my Blood.” While celebrating reconciliation, the priest says, “I absolve you from your sins. …” The priest is not simply a sign that points to Christ, but Christ acts in, and through, the sacramentality of his body.

The man called to be a priest, by God and his Church, answers that call by offering himself bodily as gift. If he does not physically place himself on the altar of the marble floor of the cathedral, place his hands within the hands of the bishop and promise obedience, and have those same hands laid upon him, the gift of the priesthood is not given to the man, nor is his priesthood received by the Church. And without this man’s gift of his embodied person, the Church is bereft of the physical presence of the Lord in the Eucharist.

At his ordination, the priest enters into Christ’s self-gift; his obedient, sacrificial gift of self is united to the mystery of the cross. “The Holy Spirit makes it possible for man to reach into the self-gift of Jesus on the cross.”8 This gift of self, realized through the power of the Holy Spirit, allowed Paul to say, “I have been crucified with Christ; yet I live, no longer I, but Christ lives in me; insofar as I now live in the flesh, I live by faith in the Son of God who has loved me and given himself up for me” (Gal 2:20). The priest, in a particular sacramental way, enters into this self-gift of Christ. In the priest, there is but one subject: only Jesus Christ. Pope Benedict XVI refers to this kenosis as the “law of expropriation,”

This expropriation of one’s person, offering it to Christ for the salvation of men, is the fundamental condition of the true commitment for the Gospel. … The personal abilities of the celebrant do not count, only his faith counts, by which Christ becomes transparent. “He must increase, but I must decrease” (Jn 3:30).

Christ’s complete obedience to the will of the Father brought redemption to mankind. The priest lives out true holiness by participating in that same self-sacrificing obedience to the Father. It is to that holiness, that presence of Christ, that the faithful respond. They see in the priest the authority and commission of Christ the Son. It is not to the person of the priest that they respond, but to Christ himself calling them and challenging them with relentless love. “The more of his own substance he {the priest} gives to his service, the more of it will be used for the fruitfulness of that service.”9

For Hans Urs von Balthasar, the primary subjectivity of the priest is rooted in obedience. In this total gift of self is the “total expropriation of one’s own private interest and inclinations so that one may be a pure instrument for the accomplishment of Christ’s designs for the Church.”10 Choosing to give this gift, Balthasar says, is part of the “decision to become a priest, and the grace to make it is conferred on the priest with the gift of sacramental grace and the indelible mark of his priesthood.”11 The priest is to orient all his gifts, “the powers of his spirit,” toward the service of God. This includes, “the renunciation of any oases of private existence or interests reserved solely for themselves. No priest can ever say he has done enough.”12 The priest is called to be holy, “to be perfect as the heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48).

For the priest, this perfection is only possible through a complete unity with Christ. Balthasar writes in his book, The Glory of the Lord, A Theological Aesthetics, Vol. I, Seeing the Form, “The saint … is holy … because he allows Christ to live in him, and it is in Christ that he ‘glories.’”13 This is his central understanding of holiness. Through the act of Kenosis, of self-emptying, Christ is allowed to fully live within the priest. Paul writes, “I am poured out as a libation upon the sacrificial service of your faith” (Phil 2:17).

In his book, The Christian State of Life, Balthasar uses phrases such as “self-surrender,” “loses his soul,” “to sacrifice and submerge his subjectivity,” “unconditional self-surrender,” “total expropriation,” and “perfect forgetfulness.”14 This holiness allows the priest to completely place himself, subjectively, at the disposal of his objective mission. The priest then, in “utterly humble openness to the Father … participate(s) in the eternal movement of the Son to the Father within the Spirit, whether this Spirit sends {missions}, the Son from the Father to the world, or from the world to the Father.”15

Although Jesus, the Son of God, made an infinite self-gift through the paschal mystery, the individual called to the priesthood must add his finite gift. Just as Christ entered into the world through Mary’s fiat, so he continues to be sacramentally present in the priesthood in the fiat of the priest. Because his freedom is finite, subjectively, the priest must continually offer himself to God. In each, self-gift to God is an act of obedience to God’s call.

The priest becomes holy, obedient to the will of the Father, through “constant contemplation of the whole Christ, through the Holy Spirit, (which) transforms the beholder as a whole into the image of Christ.”16 In this holy encounter with God, within this total gift of self, the priest begins to subjectively experience an “‘attunement’ to or ‘consonance’ with God.”17 Then through obedience, through a “deliberate attunement of self (sich-Einstimmen) to the accord (Stimmen) existing between Christ and his mandate from the Father,” 18 he strives to live out his priestly ministry in service to God’s people.

In his book, Elucidations, Balthasar offers a concise description of the role of the priest. He begins by saying, “When one is ill, one goes to the doctor, when one wants to make one’s will, one goes to a solicitor, to a specialist. But is there a specialist for God’s relationship to me?”19 Within a particular profession, the practitioner takes general principles or laws and applies them to specific instances, in this case, people. The psychologist, for example, may reflect on temperaments and see trends among people. He then seeks to help the individual to understand himself through these general principles. The doctor does the same with his knowledge of pathologies, and the lawyer with his application of civil law. So, why is that not possible for the priest?

The simple answer is that God is not governed by any law, and neither is the individual as he turns, in his uniqueness, to the unique God. Because one’s relationship with God is absolutely unique, the individual is alone in his relationship with God, and no one can fully understand, can explain, or mediate.20 Each person goes into his own private room to talk to the Father alone, and only he can follow God’s unique will for himself. In this way, no professional can guide the spiritual life of another. But the priest is called to assist in this relationship with God that is absolutely unique, without the use of worldly norms. Like the call of Levi, the tax collector, Jesus calls one person in a unique way, and neither his free and unique call, nor the behavior of the one to whom he lays claim, can be diagnosed by any socio-psychological law. In fact, Balthasar reminds us, the normal laws of human behavior—like saying good-bye or burying your loved one—do not apply.21

Within the Church, there must be one who is given the task to assist the others in their relationship with God without the use of worldly generalities.

He would consequently have to know, on the basis of his own unique relationship to God, the true nature of such uniqueness, and, at the same time, would have to have been given the special task, and with it the necessary authority, to enable him in the Holy Spirit to make it known to others, to give them appropriate directions.22

This individual must have a deep, personally unique relationship with God, and be commissioned and authorized by God, to make his incarnate word present in such a way that it cannot be manipulated, but can only be followed. A priest so embodies the authority of the Church that the individual cannot escape its demands. Yet, the way he will do this is to help me stand firm, not to run away, by being present to me with unrelenting love.23

The power to stand firm, and relentlessly witness to the love and demands of the Word, comes from the priest’s commission, which contains within it the relentlessness of God, and his own personal experience of being alone with God. Without this personal experience, “he could not even proclaim God’s word from the pulpit, but could, at the most, be a lifeless echo of what others (for example, Paul) have proclaimed of the word of God in their existence.”24 He certainly could not guide a believer in an existential confrontation that he, as priest, had never experienced. It is this existential encounter with God that makes the priest—not a professional, one who deals in laws of generalities—but one whose unique encounter with God allows him, through the authority and commission of the Church in the power of the Holy Spirit, to guide the believer in his own personal relationship in God.

As the embodiment of Christ, the priest offers himself as gift and sacrifice for the salvation of the world. This gift of self, his life of obedient sacrifice, is the language of the New Evangelization. This is the witness of evangelization that Pope Paul VI spoke of in Evangelii Nuntiandi. It is also what John Paul II meant in Pastores Dabo Vobis, when he wrote, “{It is of} absolute necessity that the ‘new evangelization’ have priests as its initial ‘new evangelizers.’”25 The priest does not simply proclaim the Good News through “tasks” of evangelization, rallying the troops as it were; he is the sacramental presence of the Word, in the midst of God’s people, leading them to salvation as the chaste spouse of the Church. The expression of the embodied self-gift of the priest is that of spousal love.

Chaste Spouse

The coming together of husband and wife in the conjugal act is an icon of the Trinitarian life of God. The spouses give themselves to each other in a complete gift of self. This gift of self in the marital union reflects the inner life of the Trinity, wherein the Father gives himself completely in begetting the Son, and the Son offers himself to the Father in the Holy Spirit. There is also a nuptial character within the life of the celibate diocesan priest. Paul makes the spousal connection most directly. “Husbands, love your wives, even as Christ loved the Church and handed himself over for her to sanctify her … that he might present to himself the church in splendor … that she might be holy and without blemish” (Eph 5:25).

Christ is the ultimate example of conjugal love lived in a celibate way. While remaining celibate, Christ revealed himself as Spouse of the Church by giving himself “to the very limit” in the paschal and Eucharistic mystery. In this way, Christ gave the ultimate revelation of the nuptial meaning of the body.26

The priest is configured to Christ through the sacrament of holy orders. Therefore, he “shares in a love for the Bride of Christ … {and} enters into a nuptial relationship with the Church.”27

What is Christ’s is his own; therefore, the priest must lay down his life for the Church, and understand that he has entered into a relationship, like marriage, for the whole of life. “The priest is called to be the living image of Jesus Christ, the Spouse of the Church.”28

The priest offers himself as a “living sacrifice” (Rom 12:1) for his spouse, the Church (cf. Eph 5:22-32). “At the consecration when the priest says, ‘This is my Body,’ not only is he offering the Body of Christ to the world, he is offering his own life as sacrifice for the Church.”29

For John Paul, celibacy for the kingdom “has acquired the significance of an act of nuptial love.”30 The celibate priest embodies the love of Christ, the groom for his bride, the Church.

Therefore, the priest’s life ought to radiate this spousal character which demands that he be a witness to Christ’s spousal love, and thus be capable of loving people with a heart which is new, generous, and pure, with genuine self-detachment, with full, constant, and faithful dedication.31

The Church, as the Spouse of Jesus Christ, wishes to be loved by the priest in the total and exclusive manner in which Jesus Christ, her Head and Spouse, loved her. Priestly celibacy, then, is the gift of self in and with Christ to his Church, and expresses the priest’s service to the Church, and the world.32

There is also an eschatological character to the celibate diocesan priest. There is a charismatic sign that points towards the “eschatological ‘virginity’ of the risen man, in whom there will be revealed the absolute and eternal nuptial meaning of the glorified body in union with God himself through the ‘face to face’ vision of him.”33 The resurrected body of the priest will be in communion with Christ, the head. The priest, in bodily communion with Christ the Groom, will be united with the bride, the Church. “In this sense, those who are celibate for the kingdom are ‘skipping’ the sacrament in anticipation of the real thing. They wish to participate in a more direct way—here and now—in the ‘Marriage of the Lamb.’”34

The Sacrament of Matrimony is the foreshadowing of the marriage of Christ and the Church (cf. Eph 5), a marriage the priest in persona Christi enters into. Therefore, the natural analogy of marriage used for the priest and the Church is, in no way fictitious, but real. As with faith, the supernatural is more real than the natural: Baptism is more of a true birth, the Eucharist is the most nourishing food, Reconciliation is the deepest forgiveness, Confirmation is the full reception of Trinitarian Life, Anointing of the Sick is the most core healing. So the supernatural marriage of the priest to the Church is the real prefigurement of the heavenly kingdom where “they neither marry nor are given in marriage” (Mt 22:30). This is the chaste, spousal love in which every soul will find its fulfillment in heaven. This kind of chaste spousality the priest enters into is not un-natural, as many say today, but it is super-natural—a call by God to belong totally to him, body and soul, in this life in anticipation of the life to come.35

Spiritual Father

Celibacy for the kingdom, in this nuptial embodiment, also has the characteristic of being ordered by nature toward fatherhood. The Holy Spirit is the source of the fruitfulness of spousal love. The unity of the married couple can also be experienced in the fruitfulness of children. “In the communion of persons in marriage, the two become one so that they may become three.”36

This is so profound that, as John Paul notes, the communion of persons is decisive for man as the image of God: Man is the image of God, not only as male and female, but also because of the reciprocal relation of the two sexes. The reciprocal relation constitutes the soul of the “communion of persons” which is established in marriage, and presents a certain likeness with the union of the three Divine Persons.37

The Holy Spirit, the same Spirit which is the principal agent of evangelization and animates the Church, is also the source of the spiritual fruitfulness of those called to the celibate life.38 The celibate marriage of Mary and Joseph is the archetype of this fruitfulness. Through the power of the Holy Spirit, Jesus Christ became incarnate in the womb of the Virgin Mary, and Joseph became a Father. The fruit of their gift of self is Jesus Christ himself.

Through the power of the Holy Spirit at ordination, the priest becomes a spiritual father. The Second Vatican Council, reflecting the words of St. Paul, “I became your father in Christ Jesus through the Gospel” (1 Cor 4:15), spoke of spiritual fatherhood. “Like fathers in Christ, they are to look after the faithful whom they have spiritually brought to birth by baptism and by their teaching (see 1 Cor 4:15; 1 Pt 1:23).”39

Just as the chaste spousality of the priest anticipates the eschatological reality, this paternity is a supernatural fatherhood. The spiritual paternity of the priesthood is real, sharing in the same joys and sorrows of every family: as he baptizes and buries, as he witnesses marriages and counsels them in failure, as he laughs and, at times, cries with all of the people that come to him as father, seeking the Father’s love and care. Recognizing the fruitfulness and generativity of his life through his spiritual children is a source of genuine joy for the priest. His life of love and service is, indeed, fecund, and so beyond him. He realizes he is a vessel—a conduit for the Father to make the Son, through the Holy Spirit, present in the world. Through this process, he does not suppress his virility, but allows God to use him, and, in turn, he experiences the joy of spiritual fecundity.40

Cardinal Timothy Dolan “comment{ing} on the notion of fatherhood as connected to the understanding of ontological permanence: … ‘Father’ is an identity based on being, not function … our people know that priesthood is more than a job, a profession, a career, or even a ministry; they know that priesthood is a life, an identity, a permanent call that changes our very being.41

John Paul II (Karol Wojtyla) was born on May 18, 1920, to Karol and Emilia Wojtyla. He had a sister named Olga, born in 1914, who died a few weeks after birth, and a brother named Edmund, born in 1918, who died at the young age of 26. By the age of 21, both of his parents were deceased, and all of his immediate family.42 His celibate commitment did not afford him the blessings of his own natural family, yet, the estimated viewership at the time of his funeral on April 8, 2005— many with tears in their eyes—was over 2 billion people. For almost 60 years, he was a spiritual father as a priest, and as the shepherd of the universal Church, he was a father to 1.3 billion Catholics for over 27 years. John Paul II was a father.

The cry of the fatherless in our millennium is deafening. No abstract explanations of fatherhood will sooth that cry, or heal the “effects of fatherlessness {which} reverberate deep in the child’s soul.”43 And it is a fact that the conduct of some priests and bishops has caused that wound to deepen. It is also a fact that there is no more powerful sign of fatherhood than that which is reflected sacramentally in the priest. The embodied fatherhood of the priest is his mission for the New Evangelization.

Conclusion

The Church is defined by her mission to evangelize. The priest, in his bodily gift of self, is an obedient Son, faithful to his spouse, and father of his children. This is the gift of the priesthood, as illumined by the Theology of the Body. The priest is the son on mission to evangelize those who have not heard of the Good News, and he is the Father who “will do anything for the good of {his} children … sacrifice{ing} for the good of {his} spiritual family”44 in the New Evangelization.

In this very challenging era, the Church has been blessed with extremely holy and gifted pontiffs. If we, as a Church, know how turbulent these post-conciliar times are, I am certain we have yet to fathom how blessed we have been by these shepherds, these holy fathers. The title “Great” in reference to John Paul II has, to this point, not been used, but there is no doubt in my mind that the Church will consistently use that title. His Theology of the Body has helped us to come to know who we are as persons created in the image of the triune God, and he became our father through his gift of self as a diocesan priest.

- Pope Paul VI, The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudiam et Spes, Dec. 7, 1965, n.27. vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_cons_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, Pauline Books and Media, 2006, p. 23 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- J. Bransfield, The Human Person According to John Paul II. Pauline Books and Media, p. 11. ↩

- John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them. p.164. ↩

- Bransfield, p.173. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Bransfield, p.173. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Christian State of Life, trans. Sr. Mary Frances McCarthy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983), p. 277. “In every sermon, in every dispensation of the sacraments, it is his privilege to distribute and bestow not only the Lord and his Holy Spirit, but, within this Spirit, also himself. He is not consumed in vain: each of his hidden sacrifices is absorbed into the divine fruitfulness that he serves. Whether his service is successful or not, he has the certainty that it is completely consumed. To the absoluteness in which he is placed by his office and which he can neither increase nor decrease, there is added the relativity of his own readiness.” ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar The Christian State of Life, 275. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p.277. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, A Theological Aesthetics. Vol. I, Seeing the Form, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983), 229. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Christian State of Life, 269-273. ↩

- Ibid., p.274. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, A Theological Aesthetics. Vol. I, Seeing the Form, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983), 242. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p.253. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, Elucidations, trans. John Riches (London: Northumberland Press Ltd., 1975), 105. ↩

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, Elucidations, 105. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p. 107. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., p. 108. ↩

- John Paul II, Pastores Dabo Vobis, March 15, 191art. 2. w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_25031992_pastores-dabo-vobis.html ↩

- Christopher West, Theology of the Body Explained (Boston: Pauline Books and Media), 289. ↩

- David L. Toups, Reclaiming our Priestly Character (Omaha, NE: IPF Publications, 2008), 143-144. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 148. ↩

- Ibid., 289. ↩

- John Paul II, Pastores Dabo Vobis, March 15, 1992, art. 22. ↩

- Ibid. art. 29. ↩

- West, Theology of the Body Explained, 281. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Toups, 143. ↩

- Bransfield, 114. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Owen G. Vyner, “The Contribution of the Sacrament of Penance to a Conjugal Spirituality: The Signification of Marriage and the Body in the Thought of Dietrich von Hildebrand and John Paul II.” (STL Thesis, University of Saint Mary of the Lake / Mundelein Seminary, 2012), 15. ↩

- Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, in Vatican II: The Conciliar and Post-Conciliar Documents (Rev. ed. Vol. 1.), ed. A. Flannery OP (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 1996), art. 28. ↩

- Toups, 148. ↩

- Ibid., 147 ↩

- Bransfield, 11-12. ↩

- Ibid., 29. ↩

- Toups, 146. ↩

Circumspectly, Fr. Vincent is very clear and explicit: priesthood entailing obedience, chastity and spiritual direction is a vivid sign of ONUS, HONOR et MUNUS. Thanks for the article!

Fr. Miller,

How do you process the Achilles heel of his papacy…his seeming failure to protect young people in the sex abuse matter after the large media coverage of the 1985 Gauthe case. Did he in fact far over estimate how much false accusations were a factor in this area based on his early experiences of false accusations against priests under communist rule? It seemed like this denial factor later protected him but not the Church from seeing the truth about Fr. Macial Maciel Degollado…which Pope Benedict quickly corrected after taking office.