In diagnosing the philosophical mentality of modernity, the Catholic novelist-physician-philosopher, Walker Percy, once wrote the following:

The distinction which must be kept in mind is that between science and what can only be called “scientism.” . . . {Scientism} can be considered only as an ideology, a kind of quasi-religion––not as a valid method of investigating and theorizing which comprises science proper––a cast of mind all the more pervasive for not being recognized as such and, accordingly, one of the most potent forces which inform, almost automatically and unconsciously, the minds of most denizens of modern industrial societies like the United States.1

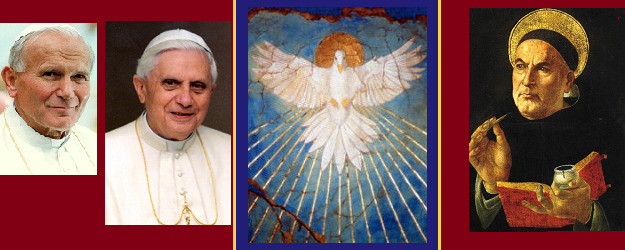

The modern mind has cultivated, both knowingly and unknowingly, what Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI referred to in his Regensburg Address “the self-limitation of reason,” a pathology that reduces the capacity of human intelligence to actually arrive at truth. This reductionist account of human knowing has stirred within modern man a philosophical relativism, a worldview that denies our ability to know anything outside of our own minds. As a result, all that we have access to is what our minds create, thereby rejecting the whole structure of reality as a given, as something already there to be known and discovered through further inquiry and investigation. For Percy, and Benedict as well, this self-limitation of reason has been coupled with “scientism,” the ideological view that reduces claims regarding truth to what can be experimentally verified in the humanistic and physical sciences. Questions regarding religion, ethics, politics, happiness, and man’s ultimate destiny become restricted as solely belonging to the domain of science, elevating both science and technology to the level of metaphysics or theology. Man is no longer a truth seeker, oriented in his being to pursue that which he was made for, but did not himself make. “Sundered from that truth,” writes Blessed Pope John Paul II:

Individuals are at the mercy of caprice, and their state as person ends up being judged by pragmatic criteria based essentially upon experimental data, in the mistaken belief that technology must dominate all. It has happened, therefore, that reason, rather than voicing the human orientation towards truth, has wilted under the weight of so much knowledge and, little by little, has lost the capacity to lift its gaze to the heights, not daring to rise to the truth of being. Abandoning the investigation of being, modern philosophical research has concentrated instead upon human knowing. Rather than make use of the human capacity to know the truth, modern philosophy has preferred to accentuate the ways in which this capacity is limited and conditioned.2

What the Pope is highlighting here is the fact that being is mind-independent, and the entirety of reality, all that is, has an integral relationship to the human intellect. At the pinnacle of this investigation of being is Being himself, the Being who is the fullness of what is, and who is without imperfection or limitation. Although it is true that the human mind is finite, and tainted by the stains of original and actual sin, it can, nevertheless, transcend the empirical, for this capacity is a given along with our created human nature. For the Pope, and Catholicism as well, human intelligence has a positive capacity to know the order and structure of reality, and can also acquire a genuine, albeit limited, knowledge of God. If emphasis is placed upon the ways in which our knowledge is limited or even deceptive, as is the case with modern philosophy, then our access to reality, to the authentic moral good, and ultimately to God, will be diminished and negated.

Contra this relativistic malaise of modernity, the Pope offers a solution pertaining to the science of philosophy, specifically outlining the sapiential character of philosophical inquiry. The Holy Father states that we must recover a philosophy that has a:

Genuinely metaphysical range, capable, that is, of transcending empirical data in order to attain something absolute, ultimate, and foundational in its search for truth. This requirement is implicit in sapiential and analytical knowledge alike; and, in particular, it is a requirement for knowing the moral good, which has its ultimate foundation in the Supreme Good, God himself. Here, I do not mean to speak of metaphysics in the sense of a specific school or a particular historical current of thought. I want only to state that reality and truth do transcend the factual and the empirical, and to vindicate the human being’s capacity to know this transcendent and metaphysical dimension in a way that is true and certain, albeit imperfect and analogical. In this sense, metaphysics should not be seen as an alternative to anthropology, since it is metaphysics which makes it possible to ground the concept of personal dignity in virtue of their spiritual nature. In a special way, the person constitutes a privileged locus for the encounter with being, and hence with metaphysical enquiry.3

What I would like to take up in this essay is the importance of philosophy for Catholicism and the life of faith. Relying upon St. Thomas Aquinas’ Commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate, I want to briefly call attention to the ever-pressing cultural need of a philosophical realism, and show why the Church has so frequently commented upon philosophical matters, and their intrinsic connection to the essence of the faith. Catholics must be more willing and ready to study philosophy in order to see its inner openness to the transcendent order, as well as to more clearly understand how it acts as a great tool at the service of theology, and the life of faith.

In his Commentary on Boethius’ De Trinitate,4 St. Thomas lays out three ways in which philosophy is necessary for theology. The first way regards what Aquinas calls the preambula fidei:

To demonstrate those truths that are preambles of faith and that have a necessary place in the science of faith. Such are the truths about God that can be proved by natural reason—that God exists, that God is one; such truths about God or about his creatures, subject to philosophical proof, faith presupposes.

Revelation proposes to man certain truths that exceed the natural capacity of human reason, truths which could not otherwise be known except by the grace given in revelation (e.g., the Trinity and Incarnation). Included within this data from revelation are certain truths that human reason, in principle, could discover on its own without recourse to revelation. The fact that God exists, that he is one, that he is incorporeal, and eternal, are all things which could be discovered through philosophical inquiry without having to look to revelation. For Catholicism, this is one of the great accomplishments and patrimony of classical philosophy, something which medieval thinkers recognized as being fully in accord with the faith.

Notice that for St. Thomas, these truths, which are accessible to human intelligence without grace, are subject to philosophical proof; to affirm that God exists is not something Catholicism holds as being true only because it is affirmed in revelation. Rather, knowledge of God’s existence—or some of his attributes—is understood through the study of his effects in the created order: an a posteriori movement from effects to cause, something which can be recognized as true in both science and philosophy. Moreover, St. Thomas is ever aware of the fact that truths in the philosophic order are not opposed to revelation, nor can they replace the grace of faith. A sapiential philosophy is needed in order to recognize the vocation of the human intellect to know the truth about the world, man, and God. This point protects both philosophical and theological reflection, for it accepts the necessity and transcendent openness of philosophy, while simultaneously proclaiming its insufficiency and demand for the light of grace.

There are, nevertheless, certain truths that can be known by natural reason that are also revealed as true. The darkness of the human intellect as a result of sin, man’s laziness, and the fact that many people will not pursue philosophical inquiry at a deep level, are reasons why God would also reveal certain truths that are of the essence of faith even though knowable by reason. Nevertheless, Catholicism places great stress upon the establishment of a genuine philosophical reason: a philosophical account that can respond to difficult questions concerning the world, the human person, and God precisely as philosophy. This is not to undermine the primacy of theology, but to give a fuller account of the natural light of reason upon which grace will build in order to correct and purify reason of its errors, while still being held together in its fullness precisely as reason.5 In this light, philosophical truths concerning God can act as a bridge leading us towards revelation, demonstrating philosophy’s integral connection with biblical faith.

Following this, St. Thomas gives a second way in which philosophy aids theology: “to give a clearer notion, by certain similitudes, of the truths of faith, as Augustine in his book, De Trinitate, employed any comparisons taken from the teachings of the philosophers to aid understanding of the Trinity.” At the heart of Catholicism is the locus of revelation: the fact that God has not only communicated with man but, even more radically, that he has communicated his own inner life. Although revelation transcends the limitations of human reason, Catholicism highlights the importance of reason in helping to further unpack, and understand, the very content of what has been revealed. The two central mysteries of the Catholic faith—the pillars upon which she stands—are the doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation. It is certainly true that we will never fully comprehend these supernatural truths, but this should not lead us to conclude that they are entirely unintelligible or, worse yet, irrational. Rather, the teachings of the faith have an innate intelligibility, and are capable, with the aid of grace, of being further understood. Although this understanding will not be complete.

This point is not to be missed, for there is always the temptation for a type of “fideism” which views a deeper understanding of the content of faith as somehow being contrary to it. The Church struggled for the first millennium to articulate and expand upon a proper understanding of the mysteries of the Incarnation, and the Trinitarian nature of the Godhead. These truths of the faith were further fleshed out and clarified with the help of important philosophical terms. The truth and reality that the terms “nature” and “person” expressed were seen not as a prelude to some sort of distortion of the primacy of revelation, whereby philosophy becomes an issue of “pride of place,” but to cultivate a deeper understanding of the faith and its supernatural truths, something which is vital for the spreading the Good News. “With regard to the intellectus fidei,” wrote Pope John Paul II:

A prime consideration must be that divine Truth “proposed to us in the Sacred Scriptures and rightly interpreted by the Church’s teaching” (89) enjoys an innate intelligibility, so logically consistent that it stands as an authentic body of knowledge. The intellectus fidei expounds this truth, not only in grasping the logical and conceptual structure of the propositions in which the Church’s teaching is framed, but also, indeed primarily, in bringing to light the salvific meaning of these propositions for the individual and for humanity. From the sum of these propositions, the believer comes to know the history of salvation, which culminates in the person of Jesus Christ and in his Paschal Mystery. Believers then share in this mystery by their assent of faith.6

What is central in this passage is the Pope’s point that the understanding of the faith (intellectus fidei) is intimately linked with the light of salvation being brought to, and received by, humanity. Among other things, one of the greatest barriers to a proper articulation and understanding of the faith is the philosophical tendencies and traditions that permeate modern culture. The scientism and multiculturalism of modernity has bequeathed to us an overly confident reliance upon the sciences as the only guarantors of truth, as well as a philosophical relativism that sees all cultures and world-views as inherently compatible with the salvific message of Gospel truth. Pluralism, so the thought goes, seems to have validated the legitimate rejection of any type of sapiential, or universal, philosophy that transcends the limitations of traditions and cultures, something which can properly evaluate their moral, ethical, and social claims. While there is much wisdom to be gained from the development of the modern sciences, and the understanding of cultural traditions, this need not cause us to substitute the pursuit of truth with mere opinion:

Reference to the sciences is often helpful, allowing as it does a more thorough knowledge of the subject under study; but it should not mean the rejection of a typically philosophical and critical thinking which is concerned with the universal. Indeed, this kind of thinking is required for a fruitful exchange between cultures. What I wish to emphasize is the duty to go beyond the particular and concrete, lest the prime task of demonstrating the universality of faith’s content be abandoned. Nor should it be forgotten that the specific contribution of philosophical enquiry enables us to discern in different world-views and different cultures “not what people think, but what the objective truth is”. It is not an array of human opinions but truth alone which can be of help to theology.7

Lastly, Aquinas points out that philosophy is needed for theology in order to defend against those who attack the faith:

If anything is found in the teachings of the philosophers contrary to faith, this error does not properly belong to philosophy, but is due to an abuse of philosophy owing to the insufficiency of reason. Therefore, it is also possible from the principles of philosophy to refute an error of this kind, either by showing it to be altogether impossible, or not to be necessary.

A healthy and flourishing theology that is authentically Catholic must be careful not to transpose philosophical disputes and arguments against the faith as being in the realm of theology, but deal with them precisely as philosophy. Catholicism does not simply use philosophy as some kind of apologetic tool, nor does it attempt to “theologize” philosophic truths, but sees the sapiential character of the truths that have been discovered and articulated by human reason qua reason as being intrinsically linked with the faith. Since faith and reason are not in opposition to each other, it follows that philosophical arguments against the faith are the result of an erroneous or distorted reason, and it will be tantamount that these claims be dealt with on philosophical grounds.

The philosophical heritage of modernity has led to a separationist understanding of science, faith, and reason, wherein science fundamentally concerns itself with reality, but religious faith or belief concerns itself with how to morally live with such a reality. As Michael Tkacz has shown,8 such a position was an attempt to hold such a dichotomy between faith and science that the believer need not abandon either his faith or his science, granted that he accepts this separationist perspective. While this mentality was thought capable of holding faith and science in a friendly relationship, it is difficult to see how scientism, and ultimately atheism, is not the end game, something that Benedict XVI spelled out in his Regensburg Address.9 It seems that one would naturally have to agree with John Searle’s remarks if the separationist account is correct:

Our problem is not that somehow we have failed to come up with a convincing proof of the existence of God, or that the hypothesis of an afterlife remains in serious doubt, it is rather that in our deepest reflections we cannot take such opinions seriously. When we encounter people who claim to believe such things, we may envy them the comfort and security they claim to derive from these beliefs, but at bottom we remain convinced that either they have not heard the news or they are in the grip of faith.10

What is this “news” that is not being heard? It is simply that science and reason have given apparent evidence for the impossibility of a world existing outside the material realm. If it is believed otherwise, this is simply for the reason that one does not know what the science actually shows, for they are being tangled “in the grip of faith.” So we must ask ourselves the following: can we make our way out of this dilemma? Indeed, the philosophical patrimony of the Church, one most especially rooted in the scholastic tradition, has provided an organic vision of the unity and order of all knowledge, and this is why she has placed such emphasis upon the restoration of philosophy, a task which is called upon:

To take up the challenge of exercising, developing and defending a rationality with ‘broader horizons,’ showing that “it again becomes possible to enlarge the area of our rationality…, to link theology, philosophy, and science between them in full respect … of their reciprocal autonomy, but also in the awareness of the intrinsic unity that holds them together.11

The crisis of post-conciliar theology, as John Paul II has specified in Fides et Ratio, has been one primarily belonging to the philosophic order. “When philosophical foundations are not clarified, theology loses its footing. Why is it, therefore, not clearer up to what point man really knows reality, and what are the bases from which he can start to think and speak?”12 In other words, theology requires a sound philosophical account of nature, the human person, ethics, political society and, ultimately, God. This credence given to the human intellect, and the ontological realities that it can understand and articulate, is the wisdom of the Church’s philosophical inheritance, a wisdom that is forever open to the illuminating light, and gift, of grace.

We need not persist in our metaphysical winter—even though Walker Percy’s humorous remark which echoes Tocqueville, and regards American philosophic attitudes, still rings true: “All the Americans I know are Cartesians without having read a word of Descartes.”13 The Church has continually stressed that the certitude of man’s confidence in knowing the world outside of his own mind, and the confidence that what we know about the external world is actually true, is the great patrimony of perennial philosophy. “The truths man could know are not just the heritage of the philosophers, but of anyone that is born into the human race. Philosophic truths are often based upon what one already knows through his experience of the world around him.”14 Faith does need philosophy, not because the former is lacking, but because the content of the faith must be made more clear and intelligible to us—those beings who are privileged to receive the salvific wisdom that is revelation. Consequently, good philosophy breeds good theology, and vice-versa. For the Church, the recovery of rigorous philosophical wisdom can only strengthen and increase the effectiveness of the New Evangelization.

- Walker Percy, “Culture, The Church, And Evangelization,” in Signposts in a Strangeland, ed. Patrick Samway, S.J. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991), 297. ↩

- Fides et Ratio, Encyclical Letter of Pope John Paul II, 1998, #5. Citations from Fides et Ratio hereafter will be given as FR and the paragraph number. ↩

- FR, #83. ↩

- Super Boethium De Trinitate, q. 2, a. 3c; trans. Rose E. Brennan, S.H.N. (Herder, 1946). All citations from Aquinas will be from the corpus of q.2, a.3. ↩

- See James V. Schall, “Possessed of Both a Reason and a Revelation,” in The Mind that is Catholic: Philosophical and Political Essays (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2008), 162-177. ↩

- FR, #66. ↩

- Ibid., #69. ↩

- “Faith, Science and the Error of Fideism,” Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture 5 (2002): 139-55. ↩

- James V. Schall has an excellent analysis of this very point in his “Protestantism and Atheism,” Thought, XXXIX (1964): 531-58. ↩

- The Rediscovery of the Mind (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 90. ↩

- Vatican Congregation for Catholic Education, “On the Reform of Ecclesiastical Studies of Philosophy,” #7. ↩

- Ibid., #9. ↩

- Walker Percy, More Conversations with Walker Percy, ed. Lewis A. Lawson and Victor A. Kramer (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993), 232-33. ↩

- See Brian Jones “That There Were True Things to Say: The Scandal of Philosophy and Demonstration God’s Existence in Thomistic Natural Theology,” New Blackfriars 95 (2014): 412. ↩

Science can be used as metaphors for Christianity too…I do so in “Everybody for Everybody” and “Soul of the Earth”:—LIVE THE LAST WORDS OF CHRIST—A POETIC EFFORT of sorts… These are the eight ensoulment “plays” to win the “game” of life by following the “rules” of life. They constitute “LOVEOLUTION” (page 616)–the revolution/evolution brought by Jesus through the Church.. Sacramental living is to participate in the pre-Big Bang Eternity.

From Samuel A. Nigro, M.D.’s books ANCIENT SECRETS, SOUL OF THE

EARTH and EVERYBODY FOR EVERYBODY:

(One of the LAST WORDS OF CHRIST can apply to every activity…

Learn ENSOULMENT (the Anthropic Schema) of the basics of Christian living—

Sacramental, universal, scientific, virtuous, transcendental

{Therapeutic.

as existing in basic physics. (Otherwise, it is entropy.)

[Mass Mantra: Life, Sacrifice, Virtue, Love, Humanity,

Peace, Freedom, Death without Fear]

“Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

“Pater, dimitte illis, quia nesciunt, quid faciunt.”

Confess into a unity spectrum giving hope and identity…

{Selective Ignoring.

“spectrum”-a splitting of energy into position-time

relationships.

[ Humanity]

“This day thou shall be with me in Paradise.”

“Hodie mecum eris in Paradiso.”

Holy Order into a dimension for Life (the Father) giving

courage and being…

{Non-Reactive Listening.

“dimension”-space coordinates (length, width,height) and

time.

[ Virtue ]

“Woman, behold thy son. World, behold your mother.”

“Mulier, ecce filius tuus. Omnes, ecce mulier tuus.”

Baptism into a dignity event giving faith and matter…

{Living Things are Precious.

“event” –a point in space-time of something certain that

happens.

[ Life ]

“My God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

“Deus meus, Deus meus, utquid dereliquisti me?”

Holy Communion into an integrity field giving charity and

truth…

{Subdued Spontaneity Non-Self Excluded.

“field” –a matrix existing throughout space and time.

[ Sacrifice ]

“I thirst.”

“Sitio.”

Matrimony into an uncertainty for Liberty (the Son) giving

temperance and good…

{Personhood…Conscious of Consciousness (C2) for the

Species.

“uncertainty” –accuracy of position is inverse to accuracy of

movement.

[Freedom ]

“It is finished.”

“Consummatum est.”

Extreme Unction into a spirit singularity giving justice and

beauty…

{Detached Warmth and Gentleness.

“singularity” –a point of space-time curvature infinity at

gravitational collapse.

[Death without Fear ]

“Into thy hands I commend my spirit.”

“In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum.”

Confirm into an identity quantum giving prudence and

oneness…

{Affect Assistance.

“quantum” –the indivisible unit of giving and receiving

energy.

[Peace ]

“The earthquake finale.”

“Il Terremoto.”

Grace into a force Pursuing the Transcendentals (the Holy

Spirit giving holiness and being.

{Make that relationship count! The Flag of Mankind and:

“I pledge to treat all humanely by caring for and respecting other’s bodies; by understanding other’s minds but being true to myself without disrespect; and by accepting the emotions of others as I control my own. I will have mercy on others with gentle liberty and empathic justice for all.” (Check out PeaceMercy.com)

“force” –that which affects matter particles—transcendental

strings between human particles.

[ Love ]

Transcendentals- one, true good, and beautiful are permanent which are impossible to objectify for they exist in every being. This common sense philosophy /metaphysics is a necessity to only assist men to join with Divine Revelation in the truth about God where men believe and live their Faith. In men objective truth must exist so love of God’s doctrines and morals may be practiced. When we catholics enter our churches for mass we dip our fingers into the Easter holy water and say while making the sign of the cross , in the name of the Father ,Son and Holy Spirit.Here we recall our Baptism and why we are here. Thank you Mr. Jones

Great Article!

I agree with the viewpoint expressed, but it seems to me we can’t simply promote ‘Philosophy’, as that will get us no further forward. So instead, I think we have to do something qualitatively different from modern, bog standard, (‘Secular’) Philosophy. Something which brings people up short when encountering it.

In most cases, Philosophy today, even in many ‘Catholic’ institutions and schools, sadly, is taught through a ‘Hermeneutic of Epistemology’. That is, even if Metaphysics is taught, it will be taught as an (outdated) branch of Epistemology; one ‘cognitive construct’ among many; or just another topic in Philosophy amongst all the others, and probably from a progressivist/historicist framework whereby the message is that Metaphysics was killed by Descartes. Ergo, to them, Metaphysics is ‘old hat’ and a left over from ‘mediaevalism’ relevant only to the ‘dark ages’.

So, it seems to me (although I could be wrong as I’m no expert), that Modern Philosophical method – ‘Normative Philosophy’ – is no help in bringing out the realities spoken about in the article, but that only a richly Catholic Philosophical method, which not only teaches the primacy of Metaphysics, but also philosophises from that viewpoint – using a rich Metaphysics as the lens (rather than Epistemology) – by which to evaluate the Philosophical project, will do.

This is why, for me, when there was a discussion on ‘A Personal Relationship with Jesus’ here on HPR, it seemed to me there is a Seculo-Protestant view of that concept (as a sort of spiritual/existential experience or ‘knowledge’) and a Catholic view of that Reality, which I think Fr Meconi rightly claims is not ‘imputed’ but ‘imparted’ – Deification – but the people I was locking horns with seemed to be focussing on the former. It seems to me that if one is participating in a reality, one doesn’t need to articulate it. So, for example, I don’t talk about a personal relationship with my mother. I just take it as a given, because it’s so real.

Going on from this thread of thought, could it be said that the Protestant and Modern Philosopher tacitly presuppose the same question – ‘Is it true?’ – whilst the Catholic and Catholic Philosopher is more likely to ask, ‘Is it real?’ (or more likely, just take matters of faith as real, as no question is required if reality ‘is’).

Going on from that, might we be making a big mistake in the New Evangelisation playing an ‘away game’ on the Seculo-Protestant turf, because it’s likely to ‘speak’ more to young people and others?

That is, by doing that are we more likely to be providing them with the ‘Catholic belief system’, simply as an alternative narrative to their current ‘belief system’, or should we be living as ‘Catholic Realists’ so that the difference is not in that to which we assent intellectually, but that to which we really assent: a completely different way of being?

In other words, if we win ‘converts’ by playing on their turf, aren’t we just playing a game of ‘bait and switch’ where we’ve lured them in, but there’s a point, where we still have to confront them with the reality that the Catholic worldview is fundamentally different, but does that End – of ‘getting them in’ – justify the Means?

I don’t think it’s a game of bait-and-switch. It’s more a way of trying to communicate to someone using their own language, and by extension, their own culture and experience. Most of the world is post-modern, and any hope of teaching it requires us to adopt post-modern constructs in order to communicate ideas. That’s one reason why the old method of rote learning (think Baltimore Catechism) really doesn’t work in today’s world. It’s not that it’s not true, but that from the recipient’s viewpoint, it’s not relevant. We’re not becoming Protestant or secular – we are reaching out to a world formed by Protestant and secular ideas. We have to recover a sense of philosophy that embraces metaphysics, while acknowledging that most folks, as Walker Percy says, “are Cartesian without having read a word of Descartes”.

Hi Dave.

Thanks so much for responding. It is really appreciated. Your points are completely valid, and I agree. What you’re saying makes perfect sense to me. My head is saying yes to everything you’ve said. But that’s my problem…

If we go by the research, people – especially the young – are rarely asking religious questions, and even if they are (to numb the pain, so anything, as long as it ‘works’), it’s simply an issue of one belief amongst many, because they’re all taught the same way – however cerebrally or rote. It simply doesn’t matter. What Fr Robert Barron portrays as a ‘Whatever’ culture. They’re all just ‘Idea Products’, in an intellectual supermarket, like those of Science, Psychology, Sociology, etc., too. As one of my lecturers, a Relativist, used to put it, ‘You pays your money and takes your choice’.

Might what one’s trying to communicate simply be distorted by their own frame of reference, or what Charles Taylor calls ‘construals’, anyway?

Dr Christian Smith, in his great book written for Protestants, How to Go from Being a Good Evangelical to a Committed Catholic in Ninety-Five Difficult Steps, is at great pains to point out that becoming Catholic, isn’t simply a change in doctrines believed, but a completely different way of being, or, taking his cue from Kuhn, a paradigm shift (correct view of metanoia?). That is, it’s not primarily an intellectual or perceptual thing. Also, he’s the guy who did the highly respected research showing that the ‘religion’ of most young people today, is what he termed, ‘Moralistic Therapeutic Deism’.

If Smith is right (which I think he is), and the implications of a metaphysical worldview is important, if not vital, as this article suggests, then might we be going in the wrong direction, despite it feeling so right?

In fact, ‘common sense’ and reasoning would dictate against what Smith and I are suggesting, because they already presuppose that very Post-Enlightenment framework, or lens, and so any alternative will, of necessity, be found wanting, because it will feel alien, outside our comfort zone.

So, I’m not ‘disagreeing’ with you to make a point for, as I said, everything in me, too, veers toward what you’re saying, but I’m trying to investigate the implications of a Doctrinal or Sacramental Realism which goes beyond the ‘chalk and talk’.

Is simply making the serious matter of faith more ‘edu-tainment’ and relevant actually going to cut the mustard? Is religion, as taught, something more like fashions and fads for the majority of people? Having to be something always radically open to change and novelty? Catholic this week, Muslim next, a bit of Krisnamurti in a couple of months? Constant revolution. Multiple, frequent, ‘conversions’.

I’ve heard it said that, ‘If you can talk a man into Christianity, you can talk him out just as easily’, and that rings true, and the well-known Protestant pastor, John MacArthur, gives cogent arguments as to why appealing to people’s emotions or will, is doomed to failure, too. So, it seems, to me, appealing to intellect, will, and emotion, all have problems with them: but aren’t those three the ones ‘postmodernism’ (sophistry) favours? That is where the ‘bait and switch’ comes in, for me. Using something to lure them in, but which isn’t what one’s real aim is.

I’m not arguing against the importance of those faculties, as I think it’s an ‘et-et’, but maybe we should take them off the pedestal, and try to envision living a faith that, if based in metaphysics, brings people up short because it’s fundamentally different, in its very nature, from all the other ‘Cartesian’ products out there that ‘Cartesians’ enjoy.

In short, the evidence of megachurches shows you can fill churches if you preach a relevant., entertaining, message – you get your product positioned properly – just like having ‘lapdancers for Jesus’ in one’s church on a Sunday would get those (normally scarce) men! But what of the Gospel is there in it? How much is there a compromise for the sake of numbers?

In fact, Dr Michael Horton, another Reformed Protestant Theologian, has a series of books based in what he calls ‘Christless Christianity’ (dumbing down for th esake of relevance/converts), and his latest is on ‘Ordinary Christianity’, as too many churches and pastors are burning themselves out through their (ineffective) quest to be relevant…

I was on the board of ‘Youth for Christ’ in our town, but the young people weren’t being given the Gospel, but a Jesus who was a placebo, and most of those who bought into that, were like addicts. ‘Jesus’ was the person who numbed the pain, like an aspirin, not God Incarnate.

In a sense, as an ex-Protestant, my insides are saying, ‘Been there, done that, and it didn’t work’, and a lot of intelligent Protestants are now coming round to that view, too, as it’s in meltdown. But, they too, are in a quandary as to what to do.

Why start down a route Evangelicals are abandoning?

In a sense, we did the ‘Social Justice’ ‘relevance’, they did the ‘Pile it high, sell it cheap’ ‘relevance’, and neither have worked, apparently. Maybe because they were simply a reflection of their own purview and questions or what they thought others really wanted, whilst those outside, don’t know what they want, or can’t articulate it, they just feel empty…?