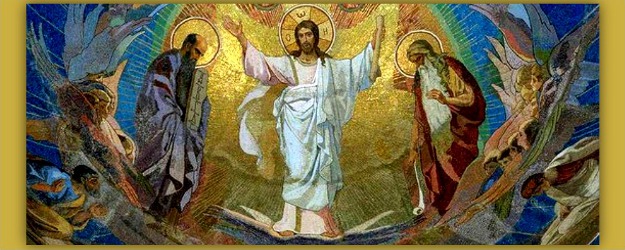

The Transfiguration, by Nikolay Koshelev (19th century).

Literature, whether in the form of narratives, plays, autobiographies, biographies, or histories, is a question-raising work of art for the inquisitive mind seeking understanding. As such, it presents what scholastic philosophy called “the state of the question” for our consideration; it calls our attention to a problem, an issue. If the art of the storyteller, or writer, deals with the formulation of meaningful questions, the art of the philosophizing listener, or critic, is in capturing something of the meaning and value of the story told. The reciprocity of literature and philosophy is similar to the two sides of the human brain, working in tandem.

Understanding the Drama of Human Life

The etymology of the word “understanding” is relevant to the same reciprocity, in the sense that the person who stands under the surface of things is the counterpart of the philosopher who seeks to get to the bottom of the human drama going on at the surface. The French have a wonderful phrase for the philosopher’s object of discovery, le drame du fond, or underlying drama, at the deepest level of human life, which is being disclosed on the surface of everyday life. Philosophers and theologians attend to the word spoken on the stage of life, anticipating the disclosure of the meaning of the word operating offstage. Persons unaware of, or indifferent to, le drame du fond, or meaning of things, are superficial—never getting beyond appearances, or the surface of our daily drama. Theirs is the meaningless, unexamined life that the Greek philosophers did not believe was worth living.

Sophocles’ play, Oedipus Rex, reminds us that tragedies, whether personal or national, can be therapeutic in opening our eyes to the deepest meaning of our lives. An outstanding Jesuit philosopher once remarked, after many years of teaching, that, generally, his best students came from families that have known tragedy. We cannot, as individuals, or a society, endure tragedies for long without wondering why. We cannot fail to understand how tragedies like the Holocaust have generated so much critical thought and reflection.

Scriptural Iconography of the Church’s Pedagogy

Narrative paintings of the lives of Jesus, St. Benedict, St. Augustine, St. Francis, and others communicated their meaning to illiterate persons, the image providing the disclosure of their meaning, and inviting the Christian faithful to enter into it. St. Francis stimulated the imagination and inspired the hearts of Pre-Renaissance and Renaissance artists. In the 13th century, his Order contributed to the new humanism that is identified with the Renaissance. The Franciscan renewal of the Church give rise to new attitudes that are associated with the spirit of the new humanism expressed in the Tuscan painters of Florence and Siena. In place of the severe figure of the Byzantine Christ, throned in awesome majesty as ruler and judge of humankind, their paintings preferred to dwell on the humanity of Jesus, the human suffering of his Passion, and the human weakness of his infancy. A new quality—sweetness—irradiates in the faces of the icons, suggesting the spiritual and psychological relationship of love among all the personages in the composition of the painting. They look at each other with affection for one another. Faces, gestures, and the composition of the pictures express affective communion. The Franciscan spirit of joyful communion with God, in humankind and nature, finds expression in the Pre-Renaissance Tuscan painters.

Franciscan humanism, rooted in the humanity of Jesus, paved the way for Renaissance humanism, with the implication that our self-image is all of a piece with our image of God—Ultimate Reality, the Summum Bonum.

The Christian community of faith employs its scriptural iconography in its pedagogy, for both ascertaining Christian authenticity and promoting Christian conversion and maturation. The Christian community does not read its scriptural iconography: rather, it approaches its Scriptures with the eye of love, which is faith, and the gaze or look of love, which is contemplation, in much the same way that Christians have for centuries approached their icons. We do not look at them as paintings in a picture gallery; rather, we contemplate the mystery they represent with the eye of love and the gaze of love that is Christian faith and contemplation. The iconographer does not “paint” an icon; rather, he “writes” an icon, because Jesus Christ is both the Image and the Word. To see the Image of God is to hear the Word of God. Jesus affirms that to see him is to see the Father, and to hear the Word of God is to hear the Father, who is speaking his Word.

God’s Contemplating Enables Our Contemplating

Verbs of seeing and hearing are metaphors for communion, community, and communication with God in our theosis, the life-long process of divinization. God’s contemplating us, with his eternal look of love, empowers us to contemplate God with the same love. God’s speaking his Word to us empowers our hearing and replying to God, in much the same way that the mother, smiling at her baby, enables her baby to smile in response. (Scripture describes persons out of touch with God as having eyes that do not see, and ears that do not hear.) The Creator God of Genesis contemplates creation with the dynamic look of love that creates, sustains, and glorifies it. In this context, John’s calling Jesus “the glory” of God—the only time in the Bible where this is predicated of a human being—affirms his uniqueness, the context for Dostoievsky’s affirmation, that beauty will save the world. It is the beauty of this perfect Image and Incarnate Word that inspires Christian theology.

We Cannot Do What We Cannot Imagine

We need our scriptural iconography and sacred icons, because we cannot do what we cannot, at least in some way, imagine. We cannot believe in, trust, love, and communicate with a God that we cannot, at least in some way, imagine. The divine pedagogy of the Incarnation appeals to the human mind and heart in Jesus Christ, whom St. Paul calls “the perfect image of God” (Col 1:15). We need a true and perfect image of God for a true and perfect worship of God. False images of God have devastating effects on both individuals and societies. Because we need true images of ourselves, others, the world, and God, for truly good decision and action, Jesus tells parables, both to give us true images of ourselves, others, the world, and God, and to liberate us from our false images of ourselves, others, the world, and God.

The art of the Gospel writers was indispensable for their effectiveness in communicating, or disclosing, the meaning of God. The Incarnate Word is communicated in the written word (Scripture) to disclose, in time and space, the God who is its uncreated, transcendent, invisible Speaker. Mark invented the literary genre called the Gospel. His creative literary genius—generally overlooked—paved the way for all other Gospel writers. Mark created a literary-theological unit, so that, the better we critically understand its literary excellence, the better we can grasp its theological significance. By the same token, the better we grasp its theological meaning, the better we can appreciate its literary excellence. We cannot fully appreciate it without appreciating all its constituents: its literary form and theological meaning. The Gospel of Mark exemplifies both the literary genius and profound inspiration of its author, which served as a model for the other Synoptic Gospel writers, who shared the same divine inspiration.

Mark’s Scriptural Iconography

Mark’s scriptural iconography is a literary and theological unit whose structure discloses the integrating center of Jesus’ life in two ways that are normative of Christian conversion. Jesus lives for divine, rather than human, approval. Mark structures his narrative to indicate that Jesus lives for God, above all. Jesus’ unpopularity is commensurate to the progress he makes in fulfilling his Father’s will. The hostility that Jesus encounters intensifies as the sphere of his activity expands. Religious leaders clash with him and decide that he must die (Mk 2:1-3:6). His family and relatives reject him (6:1-6). His disciples oppose him (8:32). The crowds turn against him (14:43; 15:14). The military mock him (15:16-20) after he has been condemned to death by the civil authorities (15:15). Disciples, friends, and family abandon him at Golgotha, where some women are described as observing events “from a distance” (15:40). Jesus dies alone. His life story culminates in obedience to his Father’s will. He enjoys no human solidarity or affirmation, but only mockery and contempt. The meaning is now clear concerning his rebuke to Peter for thinking the way of men, rather than of God (8:33), and his affirmation that God alone is good (Mk 10:18).

Jesus Shares His Interior Life of Filial Love

Jesus lives to share his interior life with all humankind. Marks makes this clear, by structuring his narrative around three authentic and full affirmations of Jesus’ identity, in which he implies that only the Lover (Father) authentically and adequately recognizes and knows the Beloved (Son). At the beginning (Mk 1:11), and during (Mk 9:7), the life story of Jesus, the Lover explicitly identifies Jesus as the Beloved. Only through the death of Jesus for “the many” (Mk 10:45; 14:24), is the Gentile centurion, the archetype of “the many,” able to share the Lover’s recognition of the Beloved.

Three Affirmations of Divine Sonship

These three affirmations of Jesus’ divine sonship make up the beginning, the middle, and the completion of Jesus’ life story. Jesus is fully aware of his God-given meaning and value, mission and purpose, from the beginning to the completion of his life story. Aware of the Lover, who has called him Beloved, Jesus is enabled to transmit to “the many,” symbolized by the Gentile centurion, the transforming and saving reality of that Lover. If the baptismal narrative reveals Jesus as the person whose very existence is that of being loved by God, the Transfiguration narrative reveals that love as constituting Jesus as the sacrament of God’s love for all humankind. The transfigured humanity of Jesus is the outward and visible sign of the inward and invisible favor that infallibly brings about that which it declares. Mark would not be writing the story of the Beloved Christ, if he and his hearers had not already heard the voice that calls him “my Beloved”: Mark is writing the story of the One who is the supreme Symbol (sacramental sign) of the Lover-Beloved relationship, the efficacious Symbol (signum efficax), which draws together all humankind to become what they contemplate.

The Inaugurating Vision of Jesus’ Life

Every human life story requires an inaugurating vision; so the Markan Jesus sees the meaning of his life’s story in the moment he starts to tell it. Jesus’ life and mission begin with the major statement of the vision from which all else springs. Mark presents Jesus’ knowledge and vision of his own beloved Sonship as the energizing source and dynamic principle which binds the disparate elements of his life story together. We can, in no way, do what we cannot, at least in some way, envision. The baptismal affirmation of Jesus as the Beloved Son of God gives Jesus the vision of who he is, and what his story should tell. Mark structures his story so that the vision which initiates the life of Jesus is present throughout his entire life story. The appreciative voice of the Father is heard by Jesus throughout the length of his saving mission. It defines Jesus as the one who, at core, is in relation to the Father; it defines the character of the favor and authority he enjoys from heaven. The baptismal account seems to imply that it was Jesus alone who heard the voice; the voice testifies to the ontological basis of Jesus’ ability to communicate the concrete goodness of being loved by God. It is because Jesus is the unique Beloved of God, that he can make us beloved. It is from this, that all else flows.

The Transfigured Transfigures

At the Transfiguration, the heavenly voice comes almost as a response to Peter’s exclamation. Peter and heaven are represented as speaking. At the Transfiguration, the representatives of the new people of God share the vision and hear the voice. Jesus is represented as transforming; the Transfigured transfigures. At the Transfiguration, a command is added to the words heard at the baptism: “… listen to him.” The Lover not only loves the Beloved, but also demands that others listen to the Beloved. The Lover’s authority is invested in the Beloved. It is witnessed by the Gentile centurion who stands for “the many” for whom Christ’s blood was poured out (Mk 14:24). “Truly,” he declares, “was this man the Son of God” (Mk 15:39). This confession of faith represents for Mark a full confession of the Easter faith in the divinity of the crucified and risen Son of God.

A Markan Model for Christian Conversion

The three affirmations of Sonship suggest a Markan model for the event and process of Christian conversion. The relationship of the three affirmations of Sonship moves from non-recognition (Baptism), through incipient recognition (Transfiguration), to full recognition (Golgotha). Mark’s readers will experience the goodness of God’s affirming love in their lives only as they allow themselves to be drawn to him along the Way of the Cross. In the self-gift of his Son, God wills to make us the locus of his own self-giving to the whole human race. In the measure that we allow ourselves to be totally receptive to God—in that measure—can God make us the fountain from which his love will flow to our brothers and sisters.

Mark’s scriptural iconography is an extended symbol of God’s self-investment in his Son, the Beloved, a self-investing Love which calls forth and creates Love in all who receive the Spirit of the Son. Mark’s Gospel summons each reader to hear the words of God: “You are my Son, the Beloved. My favor rests on you”: Mark is engaged in the cognitive-affective transformation of his readers, a transformation that issues from the felt meaning of God’s loving self-investment in their lives. Mark wants his readers to accept, as the integrating center of their lives, the Supreme and Beloved Goodness, whose life has been poured out for them. Letting God be God means letting him invest in our lives the fulfilling goodness of his Beloved Son and Spirit.

Christian Vision

No authentically human life is possible without vision, without a particular way of seeing, imagining, and feeling about ourselves, others, the world, and ultimate reality. Many elements condition our vision. Our emotions, or feelings, often exert an unexamined influence on our vision of the world and ourselves. They may be sustained by needs, as well as by values. Although we may verbalize our vision of the world, and of ourselves, in terms of our value, we may be largely unaware of the extent to which our vision and character are shaped by our emotional attitudes and needs. Our “affective memory,” the totality of our emotional attitudes, can outlive the memory of the occurrences that led to its formulation. This memory is the living record of the emotional life history of each person. It is always at our disposal, playing an important part in the appraisal and interpretation of everything around us; it can be called the matrix of all experience and action; it is also our intensely personal reaction to a particular situation, based on our unique experiences and biases. It is possible that we do not understand the extent to which our vision is preconditioned by our feelings.

We are related to the world through our feelings. Although our vision of the world, and of ourselves, is a felt relationship, it is not necessarily distorted by our feelings. There is no vision without feeling, without memory, without imagination; but we may infer, that for the “pure of heart,” they mediate the vision of God without distortion. To be pure of heart is to be purged in heart, or cleansed by purgation. It is about an emotional state that can be reached, in which the reality of God’s existence is seen directly from the clear-sightedness of the purified, emotional understanding; for we understand not only with the mind. When cleansed, the heart sees, or understands, the existence of the higher level, of God, and of the meaning of Christ.

Christian faith is a way of seeing in the darkness: it grasps the truth, goodness, and beauty of the invisible God in Jesus of Nazareth. The words addressed to Thomas (Jn 20:29) affirm, that it is the faith of those who saw Jesus, and not the sensible vision itself, which is the saving experience. To see Jesus is a saving vision, only if it is a vision of faith. It is to know and to experience the Father (Jn 12:44; 14:8-9). The New Testament believes that there is something seriously wrong in those whose physical vision of Jesus, whose experiences of his words and works, did not predispose them to see the Father in him (Jn 14:24). The saving vision of God in Jesus of Nazareth presupposes saving attitudes which predispose us to respond in a positive manner; it presupposes a readiness to grasp the full meaning of the image of God in Christ (Rom 8:28), and to have our lives (characters) shaped by it. The New Testament presupposes our openness to the mystery of God, and holds us responsible for the quality of our response to it in our personal vision of the world and of ourselves. We are judged by our vision. What we see, our sense of the world, discloses what we are. Similarly, what we fail to see discloses what we are not. Consequently, the New Testament underscores the grave condition of those who failed to see God in Jesus of Nazareth.

The maturity of Christian vision involves the whole person. Its goal is symbolized, not by the immortality of the soul, but by the resurrection of the body, as representing the total self that must be made whole. The fullness, or perfection, of Christian vision is manifest, not only in the understanding, but in the affective life, and in the loving actions that are rooted in our personal adherence to Christ Jesus.

In Christ

Our Christian vision develops in Christ, and to Christ. He is the perfect image of God, because he possesses the perfect vision of God; and he has the power to communicate what he is. He radiates his vision at every level of his existence, enabling us to be transformed by it at every level of our existence. His lived vision of the meaning and purpose of human life defined his character and personal history; he embodied the vision of God, which he preached in word and deed. The good news of the Kingdom, which he preached, touched all the dimensions of human life and existence. He called everyone to a transcendence of all that made human life less than life, and less than human. He called us to the freedom which his vision enabled him to enjoy at every level of his being: “Let not your hearts be troubled,” says Jesus in his farewell discourse. “Believe in God, believe also in me” (Jn 14:1). “Truly … he who believes in me will also do the works that I do; and greater works than these will he do, because I go to the Father” (Jn 14:12). His final commandment is “that you love one another as I have loved you” (Jn 15:17). To believe in Jesus is to believe in the Father, and to share in the Spirit of their vision, which, in turn, empowers us to achieve what he achieved, to have the same kind of impact that his life had on others.

Jesus Christ is a new and unique way of being in the world. He represents and communicates a unique way of thinking and feeling about God, the world, ourselves, evil, the past, and the future. He incarnates a new vision, a new sense of reality, and way of relating to it, a new way of experiencing ourselves and the world. He incarnates and communicates the foundational vision of the Christian community. His foundational vision is mediated through the Apostles. It is definitive and normative of Christian living. The dependent vision of individual Christians is the continuing and lived renewal of the foundational vision; it points back to the unique vision of Jesus Christ, and is called to a future of maturation in the fullness of this vision. The vision of the Risen Lord empowers the ongoing maturation of our dependent vision, within the body of Christ and the temple of his Spirit. The foundational vision of Jesus Christ is the matrix for the specific character of our dependent vision; it gives rise to those consistencies which enable our vision to be recognized and affirmed as Christian; it is evidenced by the quality of our lives in all their concreteness and specificity.

Impact of Vision on Personality

Our vision of the world is “seen” only in the concrete evidence of that vision. Our feelings and actions illuminate the authentic meaning of our words, and unveil the quality of our vision as a reality that is felt, and acted upon, and spoken. Sin, in this respect, is a lack of coherence between our vision and the rest of ourselves: the failure to feel and act in accordance with our vision. Awareness of the gap is also within our vision.

Everyone has some vision, or other, of his or her basic self-others-world-God (Ultimate Reality) relationship, which is attained in the concreteness of his or her experience, and, in turn, irradiated at every level of his or her being. Vision permeates our thoughts, desires, interests, ideals, imagination, feelings, and body language; it is our worldview, our sense of life, our basic orientation towards reality. Our vision gives rise to our character and style of life, to the tone of our being in the world. Vision is the way we grasp the complexity of life; it is the way we relate ourselves to the things of life; it involves the meaning and value that we attach to the complexity of life as a whole, and to the things of life, in particular.

Each person is the incarnation of a definite vision of God (Ultimate Realty), world, humankind, and salvation. Each person is a metaphor for God, world, humankind, and salvation. Within varying degrees of truth and falsity, each person embodies a kind of judgment about the God, world, humankind, and salvation, which he or she experiences within the consciousness of his or her vision. Inevitably, each person communicates the effects of all that is given to him or her in the experience of his or her vision. Even the affirmation—that one sees no ultimate meaning or value in a world which one judges to be an absurdity—communicates the reality of a personal vision. The experience of vision is fundamental to human life; it does not preclude a change in, or deepening of, one’s vision. Our vision of God, world, humankind, and salvation implies the way in which we envision ourselves, whether as blessed, or cursed, or both. Our vision of God, in the Christ of Calvary, evokes the self-awareness of our blessed deliverance of the felix culpa, through which we experience our being healed by the loving compassion of God in his crucified and risen Son.

Father Navone, SJ. has written a marvelous presentation of Mark and his gospel , guiding the other writers to show Jesus Christ one with the Father and shows us how to believe this doctrine and act on it with love of God and all others Thomas saw and touched the wounds and believed that Jesus is God and His teachings are true , deceiving no one.

Dear Fr. Navone,

Wow…….my spiritual life just took a step forward and upward! You have a way of explaining complicated things in a pleasing way, while at the same time…..you are coming from a huge theological background.

I see the Holy Spirit working in you………the exact role Italian blood plays in it all…would be interesting to know.

Tony