Where is that Church where “there does not exist among you Jew or Greek, slave or freeman, male or female. All are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Where are those churches where the congregations are not divided by ethnicity or language?

While meeting with the young people of the parish, I suggested that the Hispanic youth join with the other youth of the parish to form one youth group. I noted that the last speaker to the Hispanic youth group had made his presentation in English, and I recalled that when I did a bilingual Mass, the Hispanic servers would chat among themselves before Mass in English. All youth of the parish were classmates at the same high school. Why separate them into two parish youth groups?

The Hispanics rejected my suggestion, the non-Hispanics were okay with the idea, and the African-Americans were very supportive.

Of course, I thought. The civil rights’ and feminists’ efforts in the past decades have moved this country away from institutionalized separation due to sex or race. The support of the African-American youth of the parish for combining all the young people as one group was the logical statement from kids that had experienced separation and discrimination. Non-Hispanic youth had grown up with multi-racial classmates, and saw no need for a separation of youth in the parish.

The Separation Norm

Separation by ethnic or language groups has become the norm in our Roman Catholic Church in the United States. The Archdiocese of Los Angeles has Masses in more than two dozen languages (as listed on their website). Bishops and seminaries across the country encourage study of Spanish, varying from encouraging, to requiring, an ability to administer the sacraments in Spanish.

National politics adheres to the same separation norm. Congressional electoral districts have been gerrymandered until some looked like Rorschach ink blots in order to ensure African-American voters were properly represented. Now, based on the 2010 census, Hispanics seek redistricting to ensure their representation, as well.

The propensity toward separation in American society grows stronger. Where I grew up, we had considerable numbers of persons of Italian and Polish family backgrounds, whose parents, or grandparents, had come to this country to work in the coal mines, or in the steel mills. I never recall anyone being identified as Italian-American or Polish-American, we were all just neighbors. Today, we have African-Americans, Hispanics, Polish-Americans, Vietnamese-Americans, and so forth. The columnist, Leonard Pitts, points out that we are quicker to define ourselves in tribal terms, than national ones. We are African-American women. We are Jews. We are Southerners. We are conservatives. We are Mexican immigrants, etc.

The Perils of Separation

Professor Samuel P. Huntington, of Harvard University, describes a “cleft” country as a country with deep cultural differences, between sizable groups. Group identity starts to trump national identity. Breakup of the country may follow, as it did when the former Yugoslavia divided into six republics. News reports tell us of the separatist movement in the Province of Quebec in Canada, or the tensions with the Basques in Spain. By contrast, Huntington calls cultural assimilation of different groups in the United States into one society as being possibly the greatest American success story.

Huntington points out that the growing numbers of Hispanic immigrants has the goal of producing a large, autonomous, permanent Spanish-speaking community within the United States, with Hispanic social and cultural norms. Hispanic advocates seek to transform America into a bilingual, bi-cultural society.

Hispanics, according to Huntington, strive to make the United States a cleft country. He warns that such a cleavage between Hispanics and “Anglos” will replace the racial division, between blacks and whites, as the most serious challenge to American society.

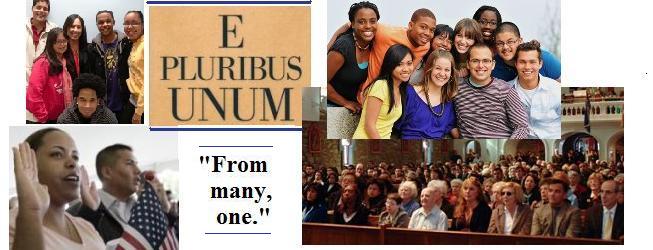

Where is the Unum?

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court affirmed a “separate but equal” doctrine, whereby states could maintain different facilities—including schools, bathrooms, and water fountains—for whites and blacks. Half a century later, the Supreme Court concluded, in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Decades of busing sought to integrate schools. Similarly, many sports programs in schools were altered to give to girls an equal opportunity with boys, after the 1972 amendment to Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

These days, hot debates are held about immigration policy. In President Barack Obama’s remarks (January 12, 2011)—after Representative Gabrielle Giffords was shot in Tucson, and following turmoil from an Arizona immigration law—he encouraged the nation to listen to each other more carefully, reminding ourselves of all the ways our hopes and dreams are bound together.

We must ask: Where is the nation Martin Luther King, Jr., dreamed about? Dr. Martin Luther King told us, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. . . . {hoping} to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands…”

Or, we can ask, where is that Church where “there does not exist among you Jew or Greek, slave or freeman, male or female. All are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Where are those churches where the congregations are not divided by ethnicity or language?

Accommodation, not Assimilation

When people of different cultural backgrounds come to live as neighbors, certain accommodations must, of necessity, follow. Here is an easy example. In colonial New England, after a week of clearing virgin forest to plant crops and build homes, the settlers would gather for a Saturday evening of fun and dancing. Each ethnic group knew the folk dances of their country of origin, the schottische, the quadrille, the jig, reel, and the minuet, to name a few. As the settlers intermingled, so did the various traditions. Eventually, a “caller” was needed to announce each dance tradition for an orderly event. Settlers learned to accommodate for each country’s tradition, which gradually gave birth to a new, American “square” dance, incorporating a bit of each dance tradition in its performance.

Foods in the United States certainly have been equally adopted and adjusted as they crossed national boundaries. Think of pizza. Both Italy and America have pizza, but Pizza Hut style pizza is only found in Italy in a Pizza Hut franchise. Likewise, a Chinese chef, reared in China, will tell you how he tweaks his recipes to suit American taste preferences. The fortune cookie we get at Chinese restaurants was invented in San Francisco by Japanese who created the cookie with a note inside in order that it be passed out at the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park in 1914. When introduced to China in the 1990s, our fortune cookies were described as American cookies.

The Role of the Church

The Roman Catholic Church, before World War I, used its clergy, schools, charity, and fraternal organizations to introduce immigrants to American customs. Contrasting that to today’s approach in our churches, do we not more likely promote division by having our Masses, religious education, and church programs in a variety of languages?

If accommodation is the way for neighbors to get along, certainly speaking a common language is an accommodation needed by persons of various linguistic backgrounds living in a contiguous geographic area of one country.

Most non-English speaking immigrants learn enough English to function in the work environment. But when these same persons, who speak English at work, come to church, they want the Mass in their mother tongue. That perpetuates separation.

And separation leads to tension. As the Hispanic population of one parish grew, the pastor decided to celebrate the Easter Vigil in Spanish in the main church, with a simultaneous Easter Vigil in English in the parish hall. Parishioners, who had been there for many years, were outraged: their contributions had built the church, and now they were being displaced.

Previous waves of immigrants resulted in ethnic churches. In Pittsburgh, I have celebrated Mass (in English) in the German church, which was on a corner adjacent to the Italian church. The Irish parish was about six blocks away. With the influx of Hispanics, the American church rejected ethnic churches, and instead began Masses in a variety of languages in local parishes. This is a notable pastoral decision which, unfortunately, has resulted in division, unhappiness, and misunderstandings.

Promoting Unum

Perhaps, parishes could promote unum (“one”) within e pluribus (“from many”) by offering classes discussing the variances between American society, and that of the immigrant’s country of birth. Many first generation Americans have stressed to me the importance of family within their birth culture, as if family were not important in all cultures. Certainly, the American family structure superficially might appear fractured, as job opportunities and modern mobility have dispersed many members of the extended family. But, spend some time in a family’s home—mothers and fathers with their sons and daughters—and one will feel the warmth and care of family members for each other. Go to family reunions and observe the hugs and laughter, and the joy of the extended family getting together. There is no culture, I have observed, that lacks strong family ties. No culture has a monopoly on the depth of love shown among family members. Let’s talk with our new immigrant neighbors about our own family values.

Many parishes offer classes on English as a second language. Besides learning the language, these classes offer opportunities for the newly arrived to get to know Americans. Cultural differences, such as family values, can be discussed. As the immigrant becomes more comfortable using English, topics could evolve into sharing insights of the scriptural readings of the weekly liturgies, or the teachings of the Church. English for non-English speaking Catholics could become an important ministry—classes led and taught by parishioners. Gradually, even swiftly, teachers and students would come to know each other, and to love each other. Caring for one another, the lifting up of each other to Christ, would naturally follow.

Difficult issues could be addressed, for example, the financing of the parish. Ask any pastor with a mixed congregation, and he will tell you the different levels of contributions of parishioners of different ethnic origin. When Hispanics are queried about their level of contributions, I have been told that it is not their custom to contribute at the levels expected of Americans. That is understandable because, in some of their countries of origin, the state provides financial support for the local parish. Who will tell the immigrant, if the church does not, that in America only parishioners’ contributions pay the bills of the parish?

Cultural days are fun. I always enjoy the various ethnic dishes cooked especially for a parish multi-cultural celebration day. The homemade tacos, or satay, or tiramisu equal and surpass that found in the best ethnic restaurants. Performances of culturally diverse music, often with native costumes, add color to the day. But cultural days need to be more a parish family celebration than a get-together of diverse ethnic groups, each with its own booth and clique. On these multi-cultural days, to stress the oneness of the parish community, I would have the Mass in English.

Works Cited:

Leonard Pitts, “In Nine Short Years, We Have Forgotten 9-11’s Lessons,” Orlando Sentinel, January 13, 2011.

Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1996) 137.

Samuel P. Huntington, Who Are We? (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2004) 183, 116, 324, 133-134.

Redemptionis Sacramentum, 112.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, 34, 3.

Or you could have the Mass in Latin and remind parishioners that the Church is universal and precedes our various ethnic backgrounds. I agree that ethnic churches are less harmful than divided multi-culti parishes.

I agree with Steve Cianca that the Holy Mass should be in Latin, which is a unifying factor world wide.

why in a time of globalization does the church promote regionalism?

why in the past when regionalism was the norm did the church insist on universality (latin liturgy)?

seems like a return to the traditional latin mass would solve many problems, not the least are:

-unity and ethnic parish problems

-the need for priests fluent in many languages

-end the liturgy wars that are sapping so much energy in the church today

-end the doctrinal battles that are also wasting the church’s energy via lex orandi, lex credendi