Preaching to a Divided Nation: A Seven-Step Model for Promoting Reconciliation and Unity. By Matthew Kim and Paul Hoffman. Reviewed by Randall Woodard. (skip to review)

A Concise Introduction to Bernard Lonergan, S.J. By Rev. John P. Cush, STD. Reviewed by Sr. Carla Mae Streeter, OP. (skip to review)

A Short History of the Roman Mass. By Rev. Uwe Michael Lang. Reviewed by M. Ciftci. (skip to review)

The Spiritual Formation of Seminarians: Learning to Live in Intimate and Unceasing Union with God. By James Keating. Reviewed by Rev. Jon Vander Ploeg. (skip to review)

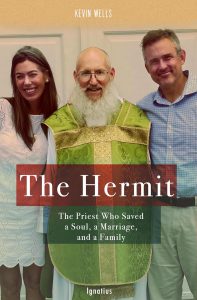

The Hermit: The Priest Who Saved a Soul, a Marriage, and a Family. By Kevin Wells. Reviewed by Lawrence Montz. (skip to review)

Preaching to a Divided Nation – Matthew Kim and Paul Hoffman

Kim, Matthew and Hoffman, Paul. Preaching to a Divided Nation: A Seven-Step Model for Promoting Reconciliation and Unity. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022. 190 pages.

Reviewed by Randall Woodard.

Readers of HPR are likely aware that the political divisions in our culture impact our faith communities as well and many might be more devoted to their political ideology than to the Gospel and Church teachings themselves. In Preaching to a Divided Nation: A Seven-Step Model for Promoting Reconciliation and Unity, Matthew D. Kim and Paul A. Hoffman address one of the most pressing challenges for clergy today: how to preach effectively in a time of profound political polarization. While written from a broadly evangelical Protestant perspective, the book’s central insights are highly relevant to Catholic priests and deacons charged with proclaiming the Gospel amid political and theological division. With pastoral sensitivity, theological depth, and practical application, Kim and Hoffman offer a homiletical roadmap aimed at healing fractured communities and inviting congregants into the reconciling work of Christ as they address the reality that “pastors, preachers, teachers, and leaders can either inflame our tensions or proclaim the peace and healing Jesus offers” (3).

Readers of HPR are likely aware that the political divisions in our culture impact our faith communities as well and many might be more devoted to their political ideology than to the Gospel and Church teachings themselves. In Preaching to a Divided Nation: A Seven-Step Model for Promoting Reconciliation and Unity, Matthew D. Kim and Paul A. Hoffman address one of the most pressing challenges for clergy today: how to preach effectively in a time of profound political polarization. While written from a broadly evangelical Protestant perspective, the book’s central insights are highly relevant to Catholic priests and deacons charged with proclaiming the Gospel amid political and theological division. With pastoral sensitivity, theological depth, and practical application, Kim and Hoffman offer a homiletical roadmap aimed at healing fractured communities and inviting congregants into the reconciling work of Christ as they address the reality that “pastors, preachers, teachers, and leaders can either inflame our tensions or proclaim the peace and healing Jesus offers” (3).

The book presents a seven-step model of preaching that moves intentionally from understanding the roots of division toward cultivating unity within the Body of Christ. The steps — beginning with exegeting the congregation and cultural moment and culminating in preaching for kingdom transformation — are carefully structured and richly supported with Scripture and examples from contemporary ministry. Each chapter outlines a stage of the model with clarity, making it a resource not just for theoretical reflection, but for concrete use in sermon preparation and pastoral planning. The authors define their assumptions and address theological questions with clarity, allowing readers to understand things denominations see differently. Additionally, each chapter ends with questions for reflection and practical next steps for developing one’s mindset and preaching.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is its insistence that preaching is never neutral. The authors push back against the temptation for clergy to avoid controversial topics for the sake of “peace.” Instead, they call pastors and preachers to enter boldly but charitably into difficult conversations — around race, political identity, economic disparity, and other sources of tension — not by offering political prescriptions, but by rooting preaching in the reconciling truth of the Gospel and by challenging readers to critically examine their own practices and assumptions. In this way, they recover the prophetic dimension of preaching while maintaining pastoral concern for the unity of the Church.

This is especially pertinent in the current U.S. context, where many Catholic parishes reflect the broader social divisions found in the nation. Preaching in such environments can feel like walking a tightrope. Kim and Hoffman help clergy move beyond simplistic political binaries and instead guide them toward preaching that fosters what they term “kingdom discourse” — a kind of preaching that transcends partisan language and invites people to imagine a shared identity rooted in Christ rather than ideology. For Catholics, the same questions, political divisions and allegiances to political ideology over the teachings of the Church are found in all parish communities.

The book is also valuable in its practical orientation. For example, the authors encourage preachers to engage in deep listening — not just to Scripture, but also to their congregations and the broader community to better understand gaps in knowledge and to better comprehend the needs of the parish. They offer helpful exercises for “exegeting the congregation,” an approach that invites reflection on the lived experiences, fears, hopes, and assumptions of one’s audience. This sensitivity to context is essential for preaching that does not simply proclaim truth in a vacuum but allows truth to land in the hearts and lives of the congregants more effectively because one knows the context and language of the parish and how to communicate the truths of the Gospel in an effective manner.

Catholic clergy will also find the authors’ commitment to reconciliation and spiritual transformation deeply resonant. While the ecclesiological and liturgical assumptions of the book are Protestant, the underlying theological convictions — that God is at work reconciling all things in Christ, and that preaching participates in this divine salvific mission — are thoroughly compatible with Catholic sacramental theology. Particularly useful is the book’s emphasis on preaching as a communal act, not merely a rhetorical performance. The notion that preaching should build up the Church as a sign of unity in a fractured world aligns well with the vision of our Church and the need for us all to put the teachings of the Church before political allegiances. Additionally, the book is very practical, offers wonderful ideas for personal reflection for all those who preach or teach, and provides a very useful appendix with numerous biblical passages related to the key themes of reconciliation from division and sin.

That said, there are limitations to the book for a specifically Catholic audience. First, the absence of sacramental and liturgical context may leave Catholic readers wanting a more integrated vision of preaching as it relates to the Eucharist, the liturgical calendar, and the broader rhythm of the Church’s life. While the book emphasizes biblical fidelity and spiritual transformation, it largely bypasses the deep liturgical and ecclesial resources that shape Catholic preaching. Catholic homilists will need to supply this context themselves. Secondly, the book does not engage with magisterial teaching or the social doctrine of the Church, both of which offer rich resources for addressing the very divisions the authors highlight. Documents from our Catechism, Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, and the wealth of papal and USCCB resources offer frameworks for Catholic social preaching that could enhance the model offered here. Readers may wish to pair this book with such sources for a more robust and distinctly Catholic engagement.

Still, these are not so many flaws as reminders of the book’s intended audience. What Kim and Hoffman offer is a thoughtful and pastorally attuned guide to preaching with courage and compassion in a time of great need. For priests and deacons seeking to navigate polarization without capitulating to it, Preaching to a Divided Nation provides both challenge and encouragement. Those who preach will benefit from the invitation into critical self-reflection that the authors provide despite some of its denominational differences. It is a book that recognizes the brokenness of our moment, but also the enduring power of the Word to heal, restore, and reconcile. It is well worth reading — and even better, worth practicing.

Randall Woodard, Ph.D., is Professor of Theology at Saint Leo University.

A Concise Introduction to Bernard Lonergan, S.J. – Rev. John P. Cush

Cush, John. A Concise Introduction to Bernard Lonergan, S.J. St. Louis, MO: En Route Books and Media, 2025. 135 pages.

Reviewed by Sr. Carla Mae Streeter, OP.

This is the book we have been waiting for. Not only clergy with scholarship behind them, but beginners who need a solid introduction for further study will find this a mind-changing read. In a tight 135 pages John Cush keeps his focus on the purpose for writing this book: to introduce his readers to the thought of Bernard Lonergan. He does this in four chapters plus an introduction and conclusion.

This is the book we have been waiting for. Not only clergy with scholarship behind them, but beginners who need a solid introduction for further study will find this a mind-changing read. In a tight 135 pages John Cush keeps his focus on the purpose for writing this book: to introduce his readers to the thought of Bernard Lonergan. He does this in four chapters plus an introduction and conclusion.

The Introduction addresses what you may have been wondering: Why Lonergan? What does he have to do with me, my ministry, and my desire to help folks grow spiritually? Cush is hearing your query, “Why all this fuss about Bernard Lonergan?” When you finish the Introduction you will know why you should read further. This thinker holds the key to the future of theology.

Chapter One gives us the background context for the person that is Lonergan. It is an invaluable sketch of Lonergan’s own philosophical and theological development. It reveals the role economics played as the concrete experiential base for what will become Lonergan’s Insight: The Study of Human Understanding. Lonergan was seeking “a stable and permanent solution for the monetary requirements of a long-term solution.”

Chapter Two takes us into pre-Insight and Insight territory. It explores the fact that Insight is an expansion of Lonergan’s Verbum text. It deals with the objective and subjective aspects of dogma, the intellectual levels of consciousness, bias, progress and decline, and Cosmopolis: not a place but a dialectical attitude of will . . . the call to authenticity.

In Chapter Three, which Cush titles “The Masterpiece: Method in Theology,” Cush introduces us to the novum organum, the new beginning, the structural instrument of philosophical tools that are key to do the job that theology needs to do. Cush is clear: this text is for theologians, those who are trained in theological skill as a ministry in the ecclesial community. This includes Background and Foreground, the emergence of historical consciousness, the emergence of the four imperatives as both personal and communal, and the ability to distinguish the successive stages in the process from data to results in the functional specialties. In short, personal authenticity and communal authenticity are both the means and the goal of the functional specialties of theology. Cush then proceeds to deal with all eight of them with pointed clarity: Research, Interpretation, History, Dialectic, Foundations, Doctrines, Systematics, and Communications, the first four mediating from culture, and last four mediating back to culture.

Chapter Four takes the reader to a discussion I have not found elsewhere in so clear a fashion: the expansion of Lonergan’s thought into the field of psychological self-understanding. The scholar leading in this rich field is Robert M. Doran, S.J. A hefty part of this work deals with Doran’s exploration of Psychic Conversion as an underdevelopment in Lonergan’s work. Due to his work in the thought of both Jung and Lonergan, Doran is capable of the task he takes on, to expand the importance of the crippling effects of dramatic bias, addressed by Lonergan in Insight. It is Doran’s work that plays a key part in making Lonergan’s Method a vital tool in interdisciplinary studies.

The Conclusion of this valuable contribution to Lonergan studies is as delightfully whimsical as it is figurative. Lonergan himself used the expression “bringing out both old things and new” in Insight, and Cush ends with a visit to a present cleaning supply closet bearing an old sign of serving as a storage area for Lonergan resources. May the reader who braves this wonderful read make the connection!

Sr. Carla Mae Streeter, OP, STM, ThD (Regis College, University of Toronto, Lonergan Research Institute, 1986) is Professor Emerita at the Aquinas Institute of Theology in St. Louis, Missouri.

A Short History of the Roman Mass – Uwe Michael Lang

Lang, Uwe Michael. A Short History of the Roman Mass. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2024. 146 pages.

Reviewed by M. Ciftci.

Fr. Lang’s book delivers what its title promises: a short history of the Roman Mass. This book is in some ways the summary of his monumental work published three years ago, The Roman Mass: From Early Christian Origins to Tridentine Reform, which was the crowning achievement of his liturgical scholarship. A Short History of the Roman Mass presents the same sweeping narrative at a fraction of the cost and in a much slimmer volume, although instead of stopping at the Council of Trent’s liturgical reforms, he continues the history up to the pontificate of Francis, with brief discussions of Traditionis custodes and Magnum principium.

Fr. Lang’s book delivers what its title promises: a short history of the Roman Mass. This book is in some ways the summary of his monumental work published three years ago, The Roman Mass: From Early Christian Origins to Tridentine Reform, which was the crowning achievement of his liturgical scholarship. A Short History of the Roman Mass presents the same sweeping narrative at a fraction of the cost and in a much slimmer volume, although instead of stopping at the Council of Trent’s liturgical reforms, he continues the history up to the pontificate of Francis, with brief discussions of Traditionis custodes and Magnum principium.

The story is familiar to anyone who has studied the Roman Rite. He begins with two chapters on the scriptural and historical origins of the Eucharist. He then moves on to the few pieces of evidence from the early Patristic period of liturgical prayers as the Roman liturgy developed during periods of persecution and peace. The story then moves into the formative centuries from the Peace of Constantine into the early Middle Ages when the Roman Canon, the collects, the Prefaces, and the papal stational liturgies that were celebrated in different locations across the city of Rome all developed during the chaos of the Roman Empire’s slow death in the West. He then covers the crucial roles played by the Carolingian kings and later the Franciscans in the consolidation of the Roman Mass and its spread over a broader area. Several chapters cover the medieval period, its eucharistic devotions, its supposed decline and decay on the eve of the Reformation, and the various changes that occurred to make lay and clerical piety more text-focused and individualistic during the late Middle Ages and after the Council of Trent, until the revival of Benedictine monasticism after the Napoleonic wars began to revive the Church’s attention to the liturgy during the nineteenth century, leading the way to the birth of the Liturgical Movement.

Lang is particularly adept at drawing attention to the attention paid by recent scholars to the role of oral improvisation and of a sacred register in the development of liturgical prayers and rites; to the early Church’s creation of sacred space, even before the first basilicas were built, by the use of makeshift altars for the Eucharist; and to the process by which different books (the sacramentary for the celebrant, the lectionary for the deacon, subdeacon, or lector, and the antiphonary for the choir) eventually were merged into the one Roman missal we use today.

What makes the book so well written is that it is written with the skill of a teacher who has years of experience in seminary education. He does not overwhelm the reader with footnotes to show off his erudition or his command of the literature. The secondary literature appears in the footnotes not as an avalanche of titles, but as a few, carefully selected titles at the bottom of each page, in case the reader should wish to delve deeper into a particular area. He also provides a glossary of technical terms used in the liturgy or in liturgical scholarship and a list of recommended titles to read. Ignatius Press failed to provide an index, although that may be pardonable for such a short book.

In polite but direct ways, Lang is not averse from revealing his disagreements with liturgical scholars from a previous generation, such as Josef Jungmann, who, for example, were too quick to dismiss the medieval era as being a time when the Patristic understanding of the liturgy was forgotten, and the noble simplicity of the Roman Rite was buried by unnecessary additions. It is not hard to draw conclusions from the book about how Lang would like to see the liturgy renewed and developed in the future, which seems to be along the lines Benedict XVI expressed in his own writings. Hopefully this book will help many to see why such a renewal is urgently needed. There is no doubt that it provides seminarians and students of the liturgy with a brief but excellent account of the history of the Mass.

Dr M. Ciftci is Custodian of the Library at Pusey House, Oxford, and the author of Vatican II on Church-State Relations: What Did the Council Teach, and What’s Wrong With It?

The Spiritual Formation of Seminarians – James Keating

Keating, James. The Spiritual Formation of Seminarians: Learning to Live in Intimate and Unceasing Union with God. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2025. 160 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Jon Vander Ploeg.

This work strikes me as being foundational for priestly formation and priestly ministry. It is imbued with wisdom that comes from years of experience in the interior life, spiritual direction, and priestly formation. This comes through from the solutions to being transformed in the Eucharist and in the unflagging call to be in actual unceasing union with God.

This work strikes me as being foundational for priestly formation and priestly ministry. It is imbued with wisdom that comes from years of experience in the interior life, spiritual direction, and priestly formation. This comes through from the solutions to being transformed in the Eucharist and in the unflagging call to be in actual unceasing union with God.

The truth that Deacon Keating does not let up on is that this union with God is the solution, and lack of it is a fundamental problem. So often we can see it as another task amid so many other tasks to get done. This is gravely false. In fact, we cannot have true life without this union, and we will be limited as priests in pointing people to the fullness of light in God if we do not live in this unceasing union ourselves.

“For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts higher than your thoughts.” (Isaiah 55:8–9) If God’s ways are higher than my ways and his thoughts are higher than my thoughts, the reality is that I have to be brought into his ways and his way of thinking. This cannot happen through a simple or even complex routine. It happens through an invitation into union with God that is responded to in the midst of life.

This book expertly sees how complex and subtle the battle lines are. There are enemies within and without. Knowing that there is a battle can help us avoid many of the pitfalls.

He begins the book with this provocative line on priestly ministry: “He ministers simply to secure a living wage, or he demotes sacred ministry to the routinized oversight of rituals and administrative duties, or he finds fulfilment in serving others” (p. 2). The first two things seem too routinized and superficial, but the third, fulfilment in serving others, is striking and true. It is a great danger in priestly formation and priestly life to use gifts and help people but not be fully living in this Intimate and Unceasing Union with God. That is missing the mark in the priest’s life and in priestly ministry.

This focus on the unceasing union with God goes all the way through the end, where he beautifully speaks about sitting in silence with spiritual directees and responding to the Lord and what he is doing in the session (171).

The current situation in the culture is challenging and this is acknowledged, along with the resistance in the seminarian that can be all too real as we engage in the spiritual life. This subtlety of picking up the nuances of the battle is what I found most impressive in the book, not because it is even the only or most important part of the book but because if it is brought up it is rarely seen accurately.

The truth is that growth in communion with God means entering a relationship in which I need to be purified. Anselm Stolz speaks about paradise in his book The Doctrine of Spiritual Perfection. In referencing St. Ambrose, he says, “After the fall, God set cherubim with swords of quivering flame in front of the garden to guard the approach to the tree (Gen. 3:24). Consequently, he who seeks to share in the glories of Paradise must first stride through this fire, that is, only he who has been purified by fire can advance further into Paradise.”1 To truly spiritually grow in union with the Living God is an experience that can easily bring up desires to escape. When you add that it is easy to forget the necessary spiritual battle or misunderstand it, we can be easily discouraged.

In the classic work entitled Satan: The Tempter’s Influence in the World and Nature, originally published by Sheed and Ward in 1951 and recently republished by Sophia Institute Press, there is a chapter by P. Lucien-Marie De Saint-Joseph, O.C.D. entitled “The Devil in the Writings of St. John of the Cross.” In that chapter he says, “The worst evil that the devil can do a soul is not by any means simply to frighten it by appearing in some repulsive form; it is to prevent that soul from cleaving to God. To deprive it of God, even temporarily, to halt it on the road toward union on no matter what pretext; to maintain it amidst the relative when in fact it is called to the Absolute; to deceive it by appearances, even pious appearances, and so to distract it from the Reality which is God: that is what the devil is after, and that is what the soul, for her part has to fear.”2

Deacon Keating masterfully picks this reality up. Deacon Keating points out correctly that “seminaries are a supernatural battleground where Satan wishes to do one thing: Stop clerics from praying” (61). Even though we may be aware of the enemy’s existence and may think of very real and dramatic things happening through the enemy and through individuals cooperating with him, it is often unseen what he is after the most.

The goal of the enemy is to prevent or delay union with God. Our fallen nature resists this union with God as does the world. Deacon Keating has done a great service for priestly formation and priestly ministry through the writing of this book.

Rev. Jon Vander Ploeg is Director of Spiritual Formation at Saint Paul Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota.

The Hermit – Kevin Wells

Kevin Wells. The Hermit: The Priest Who Saved a Soul, a Marriage, and a Family. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2024. 231 pages.

Reviewed by Lawrence Montz.

The Hermit is the story of a family in crisis. A marriage that was being destroyed by alcoholism and miscommunications. A couple losing love until the husband, Kevin Wells, sought the prayerful aid of a holy priest who became closely involved in their struggle with evil. Kevin Wells, the author and protagonist, a onetime sports writer turned evangelist, is president of the Monsignor Thomas Wells Society. Monsignor, who was murdered in his own rectory, was the author’s uncle. His example inspired Kevin Wells to found the Society to help promote and support Eucharistic adoration and vocations. He began an outreach to the priesthood exemplified in his book, The Priests We Need to Save the Church, which urged the episcopate to follow the sacrificial example of Christ. The author’s own call to the Lord’s service did not occur without several personal pitfalls and deep prayer, many highlighted in The Hermit.

The Hermit is the story of a family in crisis. A marriage that was being destroyed by alcoholism and miscommunications. A couple losing love until the husband, Kevin Wells, sought the prayerful aid of a holy priest who became closely involved in their struggle with evil. Kevin Wells, the author and protagonist, a onetime sports writer turned evangelist, is president of the Monsignor Thomas Wells Society. Monsignor, who was murdered in his own rectory, was the author’s uncle. His example inspired Kevin Wells to found the Society to help promote and support Eucharistic adoration and vocations. He began an outreach to the priesthood exemplified in his book, The Priests We Need to Save the Church, which urged the episcopate to follow the sacrificial example of Christ. The author’s own call to the Lord’s service did not occur without several personal pitfalls and deep prayer, many highlighted in The Hermit.

Wells became aware of his wife’s drinking problem after his near death experience. Already a follower of Christ, he was unable to successfully address her aberrant behavior despite what he felt was a deep prayer life seeking the Lord’s intercession. However, through persistent prayer coupled with the intercession of a holy priest, Fr. Martin Flum, her addiction was brought under control. When discussing the writing of their deeply personal story, he suspected that she might not like the idea of her travails being exposed; but she told him he was mistaken as she felt that the journey was not about her but about a brave priest, indicating that she wanted Kevin to “Show people what he did to save my life during the pandemic — how a man behaves.”

The author discovered that his efforts to control Krista’s addiction were flawed because he made the mistake of not appreciating her personal shame. Kevin tried to surrender Krista to God daily but failed to see her situation improving. In the beginning any suggestions he might make, no matter how sincere he thought they were in purpose, tended to provoke arguments and denial if not outright attacks on his motives. His prayers seemed to be ineffective and his efforts, such as promoting counseling and urging her involvement in church-related activities, did not bring about the hoped-for transformation. Eventually Kevin began to understand that his prayers for change were more about his desires and not God’s will. They were not directed to the Lord but to his own yearnings. He was unable to completely trust in God’s benevolence. Gradually he learned to be more open to God and indifferent to his needs, becoming less self-centered. His prayers became less about Kevin’s wants and more about Krista’s needs.

Fr. Flum counseled Kevin not to be discouraged by the seeming ineffectiveness of his prayers on Krista’s behalf but to be more fervent and encouraged increased fasting and self-denial so that God would heal her. More importantly, he advised patience. Inspired, Kevin invited Fr. Flum to come to a future dinner at his home to meet Krista, but to his chagrin later forgot about the invitation while away on a mission trip. When Fr. Flum showed up at their home, Krista, not knowing of the invitation and in no mood to speak with a priest, rudely turned him away.

Very gradually Krista began to look outside of herself and to God, seeking reconciliation with the Lord, at least in her own fashion. She went to confession and reencountered Fr. Flum. Like many distressed souls, Krista did not cite her addiction during that first confession but recognizing her need for further healing, readily agreed to meet with him the following day. Ultimately she learned that her struggle was a lifelong flight from Jesus rather than an acceptance of his love and desire for her good. The counseling sessions with Fr. Flum would produce a change in Krista, but after a week or two the devil would pull her back to the dark place in her soul and her drinking obsession would reemerge.

The influence of a holy priest on the lives of believers cannot be underestimated. Fr. Flum was not her only priestly guide but his example, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, played a crucial role in Krista’s spiritual and physical recovery. The book reads like a mystical journal reflecting on the Wellses’ growth in trust in the Lord’s providence, all centered on the circumstances of Krista’s alcoholism and her struggles to overcome the addiction that impacted her and her family. Until she surrendered to God’s embrace, she could never truly encounter his majesty and love or redeem her family’s harmony.

Lawrence Montz is a Benedictine Oblate of St. Gregory Abbey, past Serran District Governor of Dallas, and serves as his Knights of Columbus council’s Vocations Program Director. He resides in the Dallas Diocese.

- Anselm Stolz, The Doctrine of Spiritual Perfection, trans. Aidan Williams, O.S.B. (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. 2013), 29–30. ↩

- P. Lucien-Mare De Saint-Joseph, OCD,“The Devil in the Writings of St. John of the Cross,” in Satan: The Tempter’s Existence in the World and in Nature, edited by Fr. Bruno De Jesus-Marie, O.C.D. (Manchester, NH, Sophia Institute Press, 2024). ↩

Recent Comments