The Singing-Masters: Church Fathers from Greek East and Latin West. By Aidan Nichols. Reviewed by Fr. Peter Heasley. (skip to review)

Wisdom of Solomon. By Mark Giszczak. Reviewed by Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ. (skip to review)

Made New: 52 Devotions for Catholic Women. By Jenna Guizar, Nell O’Leary, Brittany Calavitta, Leana Bowler, and Liz Kelly. Reviewed by S.E. Greydanus. (skip to review)

Prison Journal, Volumes 2 and 3. By George Cardinal Pell. Reviewed by Maria Cintorino. (skip to review)

The Singing-Masters – Aidan Nichols

Nichols, Aidan. The Singing-Masters: Church Fathers from Greek East and Latin West. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2022. 343 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Peter Heasley.

In The Singing-Masters, Dominican Father Aidan Nichols provides a survey of the Church Fathers worthy of spiritual reading. Each of the sixteen vignettes — of eight Greek Fathers and eight Latin Fathers — tells the tale of theology as more than an intellectual exercise, and as it ought to be, a lived experience. Nichols vividly depicts theology as done not just on one’s knees but achieved as conflict, in exile, and with barbarians at the gates. These are “patristic figures who have the best claim to the attention of modern theology students,” he states in the Preface (p. 11). Nichols reminds us of Origen’s dictum, “The end is always like the beginning” (p. 53), and by weaving the personal stories of the Fathers into an exposition on their theology, Nichols provides those pastors and scholars of us living at the end of another age with spiritual models to imitate.

In The Singing-Masters, Dominican Father Aidan Nichols provides a survey of the Church Fathers worthy of spiritual reading. Each of the sixteen vignettes — of eight Greek Fathers and eight Latin Fathers — tells the tale of theology as more than an intellectual exercise, and as it ought to be, a lived experience. Nichols vividly depicts theology as done not just on one’s knees but achieved as conflict, in exile, and with barbarians at the gates. These are “patristic figures who have the best claim to the attention of modern theology students,” he states in the Preface (p. 11). Nichols reminds us of Origen’s dictum, “The end is always like the beginning” (p. 53), and by weaving the personal stories of the Fathers into an exposition on their theology, Nichols provides those pastors and scholars of us living at the end of another age with spiritual models to imitate.

Each of the vignettes runs about twenty pages of Nichols’ lucid prose. The first half of the book portrays eight Greek Fathers — Origen, Athanasius, the Cappadocians, Cyril of Alexandria, Denys, Maximus, John Damascene. He begins, though, with Irenaeus of Lyons, who is a disciple of Polycarp in Smyrna and eventual bishop of Lyons, which Nichols reveals as a primarily Greek-speaking church among the Celts in the western part of the Roman Empire. Opening the book with a Greek transplant to the West allows Nichols to introduce us to a term perhaps lost on too many over the millennia, the “Great Church,” which neatly describes the unified church of East and West from 180–313 AD. Facts like this found throughout the book are not mere theological Easter eggs; for instance, when Nichols tells us that Denys the Areopagite invents the word “hierarchy,” it is to introduce us to Denys’ understanding of an order of revelation that moves from moral purification, through mental enlightenment, to union with God (and not a pyramid of bishops, priests, and deacons). Another stunning example of forgotten insight is Origen’s understanding of the literal sense of Scripture not as what the human author intends, but as the “vehicle” for what the human author intends; such a distinction, lost on many modern exegetes, should aid especially in the kinds of narrative criticism that are (rightly, in my opinion) so much in vogue these days.

The spiritual archaeology of these essays continues into the Latin Fathers — Tertullian, Cyprian, Ambrose, Jerome, Augustine, Leo, Gregory, and Bede. It comes as a surprise to this reader to learn that the model of bishops as strictly governing geographical territory does not apply universally in the Great Church and comes largely at the insistence of Cyprian in Carthage. Such an understanding of church governance is lost on the Celts, whose bishops rule within the clan system; later on, Gregory the Great and his envoy to the British, Augustine of Canterbury, must confront “a form of Church life far more markedly monastic and charismatic than administratively episcopal and territorial” (p. 300). In our highly interconnected world today, we see a similar ecclesiastical tribalism reemerging, in which the faithful shop for parishes and cling to content providers whose ideologies match their own. Not all of what Nichols unearths is as directly applicable to modern practice as he claims, though: in a presentation on Tertullian’s dispute with the bishops’ claims to absolve serious sin (apostasy, idolatry, blasphemy, adultery), Nichols draws too short a connection between the bishops’ mitigation of public penance by invoking the merits of the martyrs and the modern practice of granting indulgences; in a survey of Gregory’s correspondence, he too quickly skips from recording letters bequeathing landed property to the Church to calling the apostolic see an “investment corporation” dogged by financial scandals for over a millennium (p. 291). Instead, the value of this book is in the recovery of a rich and variegated theological tradition and Nichols’ balanced assessment of what he finds.

There are, in this reader’s opinion, two glaring omissions, one Greek and one Latin. Nichols, himself, admits to not treating John Chrysostom, whom, even if he is simply a “preacher of the moral life” (p. 11, note 1), cuts such a large figure in the patristic interpretation of Scripture and church-state relations that he should not be left out. Nichols makes only a few passing mentions of Hilary of Poitiers, who, as another Greek-influenced bishop of Gaul (like Irenaeus), deeply informs, in turn, the thought of Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome. No one would object to this very readable tome being another thirty or forty pages longer.

They will make the most of this book who already have some introductory orientation to the Fathers in a formal or informal course of study. Those overly committed to systematic theologies, like those of Thomas Aquinas or Karl Rahner, as well as those who shun dogmatics as a perceived offense against an effervescent version of the Holy Spirit, may happily discover in Nichols’ unpolemical essays that the universal Church has come to express the wholeness of her truth in the mouths of very different kinds of teachers singing in unison of faith.

Rev. Peter A. Heasley, S.Th.D., serves as pastor of the Parish of Corpus Christi and Notre Dame in New York City. He is also adjunct professor of Scripture at Saint Joseph’s Seminary (Dunwoodie).

Wisdom of Solomon – Mark Giszczak

Giszczak, Mark. Wisdom of Solomon. Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2024. 203 pages.

Reviewed by Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ.

The Wisdom of Solomon, also known as the Book of Wisdom, is part of the Old Testament wisdom literature, along with Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Job, and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), found in Catholic and Orthodox Christian traditions. One opinion is that the book was written to defend the Jewish faith and tradition, providing guidance to young Greek-speaking Jews in the diaspora, particularly in Alexandria, Egypt, wrestling with their Jewish faith during the Hellenistic period (22). It offers insights and advice on the pursuit of wisdom, i.e. God, by interweaving Hebrew doctrine and Greek philosophy.

The Wisdom of Solomon, also known as the Book of Wisdom, is part of the Old Testament wisdom literature, along with Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Job, and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), found in Catholic and Orthodox Christian traditions. One opinion is that the book was written to defend the Jewish faith and tradition, providing guidance to young Greek-speaking Jews in the diaspora, particularly in Alexandria, Egypt, wrestling with their Jewish faith during the Hellenistic period (22). It offers insights and advice on the pursuit of wisdom, i.e. God, by interweaving Hebrew doctrine and Greek philosophy.

Wisdom of Solomon by Mark Giszczak, professor of Sacred Scripture at Augustine Institute, is a valuable addition to the Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture (CCSS) series. The series offers a Catholic perspective, integrating Catholic doctrine, liturgy, and moral living. It aims to “serve the ministry of the Word of God in the life and mission of the Church” (11) and to help people “understand their faith more deeply, nourish their spiritual life, or share the good news with others” (12). The methods of interpretation employed are historical and literary criticism, as promoted in the Vatican II’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum), which stresses the connection between Scripture and Tradition. Giszczak has achieved the stated objectives of the series.

Wisdom of Solomon follows the three-part structure traditionally accepted by scholars. It begins with an introduction that provides a general description of the book, including its structure, theological themes, location, date, purposes and audience, connection to the New Testament, and its relevance for today. Although brief, the author packs a lot of information in the introduction. The first part, “Life and Death” (1:1–6:21), contrasts the wicked and the righteous and their fates at the final judgment. Those embracing and pursuing wisdom will receive eternal life; those rejecting wisdom will be condemned. The second part, “Solomon’s Pursuit of Wisdom” (6:22–9:18), focuses on wisdom, wealth, and power. Speaking through the voice of Solomon, the author reiterates that Solomon’s pursuit of wisdom is rewarded with riches, comfort, and a long life. The third part, “The Book of History” (10:1–19:22), describes the role of wisdom in early Israel’s salvation history, including God’s power, mercy, and protection of the people of Israel. The Wisdom of Solomon fittingly ends with a doxology, praising God and salvation: “For in everything, O Lord, you have exalted and glorified your people; and you have not neglected to help them at all times and in all places” (19:22; cf. 190).

Since the Wisdom of Solomon is canonical in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions but not in the Protestant tradition, and since it has not been given much attention by biblical scholars, this monograph by Giszczak is a welcome contribution to the Wisdom of Solomon studies. Its reliability and readability stand out, making it accessible to many readers. Although the commentary is aimed at lay readers and college students, Giszczak maintains critical, scholarly depth. He judiciously pays close attention to historical and literary details to help readers understand the subject more deeply. Under each studied passage, readers will find cross-references to Scripture, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, and the Lectionary when applicable. Interspersed throughout the book are sidebars to provide additional historical and theological information to help readers better understand the biblical background and how historians, saints, and church fathers understood and interpreted the specific texts.

The “Biblical Background” sidebars cover topics such as the Greek concept of the soul (pschycē), the concept of immortality in the Old Testament, the Egyptian goddess Isis and wisdom and animal worship in ancient Egypt, and Hades in Greco-Roman mythology. The “Living Tradition” sidebars connect biblical texts to Catholic tradition and practice. They generate fuller engagement with the postbiblical teaching of the church, such as St. Gregory the Great’s comments on the cardinal virtues, St. Irenaeus’ interpretation of Adam’s salvation, the church’s teaching on God’s sustaining creation in existence as in the Catechism of the Council of Trent, and St. Augustine’s take on the seven gifts and seven evils.

The “In the Light of Christ” section highlights how specific texts anticipate or point to Christ’s coming and his redemptive work in the New Testament. As St. Augustine famously stated in his Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount, “The New Testament lies hidden in the Old and the Old Testament is unveiled in the New.” The “Reflection and Application” section, sporadically inserted at the end of some interpretive discussions, provides inspiring reflections to help readers apply Scripture to their Christian life today or deepen their faith. The reflections are well written; however, they are too few and short. It would benefit readers if more were included. A glossary of key terms and a short list of suggested resources are provided at the end of the book.

The CCSS is written by leading Catholic scholars. The New Testament series has been well-received by readers. Giszczak strives to continue its success with this commentary on the Wisdom of Solomon of the CCSS Old Testament series. With depth and conciseness, this volume is a reliable entry-level source for Catholic pastoral ministers, lay readers, and students interested in the Wisdom of Solomon.

Fr. Vien V. Nguyen, SCJ, is a priest and provincial superior of the Priests of the Sacred Heart (Dehonians or SCJs) in the United States. Holding a doctorate in Sacred Scripture from Santa Clara University, Fr. Vien was an assistant professor of Sacred Scripture at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology in Hales Corners, Wisconsin, before his election to provincial leadership in 2022.

Made New – Blessed Is She

Guizar, Jenna, with Nell O’Leary, Brittany Calavitta, Leana Bowler, and Liz Kelly. Made New: 52 Devotions for Catholic Women. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2021. 216 pages.

Reviewed by S.E. Greydanus.

This collection of brief, simple meditations, another instance of the increasingly popular genre of daily or weekly reflections (weekly in this case), reads like a discussion among friends doing group lectio divina and each sharing her thoughts. Indeed, the setting from which it comes is much like that.

This collection of brief, simple meditations, another instance of the increasingly popular genre of daily or weekly reflections (weekly in this case), reads like a discussion among friends doing group lectio divina and each sharing her thoughts. Indeed, the setting from which it comes is much like that.

Infused with the warm, gentle, homespun spirituality characteristic of Blessed is She, a Catholic women’s organization designed to foster community and spiritual growth, the five sections are each written by one of the group’s members, including the founder, Jenna Guizar. Each of the 52 weeks distills a Scripture verse and an episode from the author’s life into a three-page reflection, always encouraging, sometimes containing a very gentle, affirming challenge. Many of the readings, especially in the earlier chapters, focus on healing inner wounds and learning to accept God’s love.

The sections are divided according to a set of five B’s: “Beheld, Belong, Beloved, Belief, Becoming.” The back-cover blurb explains:

-

your worth comes from being utterly beheld by God.

-

you belong to God’s family regardless of others’ approval.

-

you are unconditionally beloved by God.

-

your belief in yourself is rooted in God’s belief in you.

-

you become more you by following God’s path for your life.

Often these distinctions are little more than nominal—most of the chapters could fit under several or even any of these categories—but the divisions by category are not the most important aspect. Rather, in each section the author offers what she has learned in her own journey with the Lord.

The sections proceed, mostly chronologically, through each author’s life. Some chapters are labeled according to stages in life (“Childhood” “School” “Young Adulthood”) and others to contemporaneous aspects of life (“Friendship” “Workplace” “Relationship with the Lord”). The diverse lives revealed here will likely offer readers of many backgrounds something with which to identify. Incidents of simple, everyday significance are interspersed with stories including: broken families of origin, loss and recovery of faith, facing work demands contrary to Catholic morality, premarital sex, and having to wait many years to find a husband or to conceive a child. Other traumas are subtler but nonetheless serious, childhood incidents whose effects the authors may not have known how to explain at the time, even to themselves.

The descriptions are not graphic or overly dramatic, but simple and straightforward, focusing on how God’s grace and mercy followed each woman through stormy times. The openness — or, as the authors like to say, vulnerability — regarding these painful, frightening, or otherwise dark experiences offers those with similar stories an encouragement not to hide their wounds, and perhaps to revisit them in a new light. Others who have been blessed with a smoother path may find here an invitation to empathy.

Happily, and not surprisingly, one also sees how grace works through moments of significant joy, particularly in special relationships and episodes of spiritual encounter. One of these was possibly the most touching description of a birth I have yet read.

The book does not aim to be lofty theology. It is a collection of thoughts written in an everyday style, sincere and straight from the heart, the deeply personal fruit of experience and prayer. The readings are by and for busy mothers and working women, who may only have time for a short meditation, and more of whom may be carrying some bitter memory or other inner burden than one might think. Made New will likely be of particular benefit to those who especially need a boost of affirmation, whether suffering from insecurity, scrupulosity, or some other form of nagging fears. Yet for probably any Catholic woman, unless perhaps she prefers more robust spiritual reading, a collection so brimming with wholesome encouragement for her Christian life has potential to be a welcome supplement.

S.E. Greydanus is a freelance writer/editor and managing editor of Homiletic & Pastoral Review.

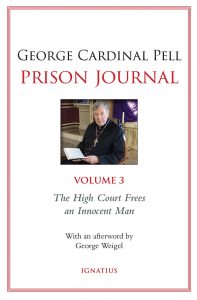

Prison Journal, Volumes 2 and 3 – George Cardinal Pell

Pell, George. Prison Journal, volume 2: The State Court Rejects the Appeal. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2021. 319 pages.

Pell, George. Prison Journal, volume 3: The High Court Frees an Innocent Man. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2021. 339 pages.

Reviewed by Maria Cintorino.

How does one endure times of trial, false accusations, thirteen months of solitary confinement, while awaiting an impending decision of the Australian legal system which would determine one’s name and the next six years of life? For Cardinal Pell, the answer was prayer, coupled with routine, writing, and reading a multitude of well-wishers’ letters.

How does one endure times of trial, false accusations, thirteen months of solitary confinement, while awaiting an impending decision of the Australian legal system which would determine one’s name and the next six years of life? For Cardinal Pell, the answer was prayer, coupled with routine, writing, and reading a multitude of well-wishers’ letters.

The second volume of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal, The State Court Rejects the Appeal, spans from Weeks 21–40 of imprisonment: July 14–November 30, 2019, while the third volume, The High Court Frees an Innocent Man, details Weeks 41–59: December 1–April 8. Writing faithfully daily, the Cardinal fills countless pages with spiritual reflections, musings on various topics, his decision to appeal to the Australian High Court, the process of doing so, and the mundane life of solitary confinement.

In both volumes, the Cardinal diligently prepares notes for his appeal. He often reflects on his accuser’s story. Though he records the impracticality of both timing and place, stated in the allegations, he bears no ill will towards his accusers, nor to the judges who sentenced him to six years’ imprisonment. Instead, Pell feels sorrow toward them while dutifully proving his innocence. He pores through articles detailing the allegations, reads the court reviews, and recounts meetings with his lawyers. Throughout his entries, he emphatically insists upon his innocence, knowing that proving his good name is vital for the Church’s good in preventing other miscarriages of injustice.

Though Pell occasionally admits experiencing frustration and is tempted to impatience regarding his present state, he sees no sense in dwelling on these feelings. Instead, he exemplifies how any Christian ought to bear his cross. He maintains hope amid darkness, uniting his sufferings to Christ’s. He writes: “No one escapes suffering. The challenge for a Christian is to use suffering properly, so that it strengthens faith, hope, and love in the patient, family and friends” (Vol. 3, page 327).

Though Pell occasionally admits experiencing frustration and is tempted to impatience regarding his present state, he sees no sense in dwelling on these feelings. Instead, he exemplifies how any Christian ought to bear his cross. He maintains hope amid darkness, uniting his sufferings to Christ’s. He writes: “No one escapes suffering. The challenge for a Christian is to use suffering properly, so that it strengthens faith, hope, and love in the patient, family and friends” (Vol. 3, page 327).

And Pell shows how he strives to suffer well in his journals. He relays the trials of prison life — the occasional abuse he received at the hands of other prisoners, the strip searches, mail confinement, the ever-changing rules of prison life, the prohibitions of seeing his visitors on the scheduled days — and he mourns the inability to celebrate Mass. At other times he humorously accounts other inconveniences, noting when he has another “shouter” in the unit.

Despite these hardships and unjust imprisonment, Pell maintains a spirit of humility. The privations of prison life he records simply as the occurrences of daily life. He expresses gratitude toward his guards, commenting on their kindness and the humane conditions which exist in the prison. Confined to his prison cell and unable to interact with anyone, Pell still acts as a spiritual father. During his imprisonment, the cardinal received approximately four thousand letters — from fellow prisoners, believers, and non-believers alike who encouraged him, providing some solace. Though Pell could not answer the multitude of letters sent, he always replied to his fellow prisoners and prayed a Memorare for those who requested prayers.

Pell’s example during solitary confinement, evidenced in his books, encourage and instill hope for those who experience dark days. Like the works of St. Thomas More, Fr. Walter Ciszek, Fr. John Gerard, Cardinal Van Nguyen, and countless other heroic men and women who unjustly suffered imprisonment, the Australian cardinal’s journals witness to the power of God’s grace. They serve as an enduring testament to the prelate’s faith and hope: a reminder that the faithful God sees all and works all for the good despite the trying circumstances which life presents. The cardinal perhaps best describes how his faith helps shape how he views his predicament. He quotes George Bernanos, a Catholic author: “The only way to reform the Church is by suffering for her. One reforms the visible Church only by suffering for the invisible Church . . . The Church doesn’t need reformers. She needs saints” (Vol. 2, page 299).

And Pell uniquely understands and lives this. In his confinement, the reader glimpses into a Christian life — offered for the Church — lived well, despite unfavorable conditions and a seemingly insignificant routine. The imprisoned cardinal transforms prison’s life tediousness by praying constantly and living steadfastly in the darkness of faith. He offers his day for others — for newly-ordained priests, nuns making their profession, a woman undergoing a surgery — and structures his day well.

He keeps himself on a schedule in prison, trying not to deviate from it as prison life affords. Restricted from celebrating the liturgy, Pell wakes in time for the 6am Mass at Home for You. He faithfully makes time for meditation and prays the rosary and breviary. When prayer becomes difficult, he follows the advice of one of his correspondents: he recites hymns. He exercises weekly, rejoicing in small improvements: walking for seven minutes on the treadmill, or achieving an unbroken 300-stroke table tennis streak. And he reads, tackling Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Hobbes’ Leviathan, plays Sudoku, and watches cricket.

Sundays incite other inspiration through the evangelical preachers Joel Osteen and Joseph Price. Though Pell criticizes their prosperity Gospel preaching, noting a lack of emphasis on conversion, he notes his gratitude toward them as their preaching helped nourish him during confinement, provides the means to examine their message, and deepens his appreciation for the liturgy and the Church’s structured liturgical year.

Pell’s diary entries span a variety of topics which will fascinate any reader. From theological treatises, daily meditations, current ecclesial and social events and controversies, historical interests including the royal family and Winston Churchill, cricket, music, and the mundane occurrences of his day — requesting a new alarm clock, a swollen knee, the weather, a cold pasty for dinner, and indulging each night with a piece of chocolate — Pell simply and humbly recounts his daily circumstances, thoughts, and reflections.

Though it was written amid great suffering and injustice, any reader will discover Pell’s literary work to be uplifting. Shedding light into the cardinal’s soul and ruminations, the diaries supply much food for thought and fosters one’s own meditation. As such, these journals cannot help but greatly enrich each reader’s life. Written with an unwavering determination in God’s providence, Pell’s prison journals convey a steadfast message of hope and offer a wealth of practical advice, beneficial to both clergy and laity alike.

Maria Cintorino writes from Virginia. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including National Catholic Register, Our Sunday Visitor, Dappled Things and Crisis Magazine.

Recent Comments