The presentation of our holy faith is often hobbled by a failure to demonstrate the organic unity of its constituent parts, a problem much lamented by Pope Francis, who has observed that Christianity is frequently reduced to a “disjointed . . . multitude of doctrines” (Evangelii Gaudium 35). Nowhere is this tendency more acutely felt than with respect to the radical connection between the cross, God’s self-revelation in Christ, and man’s identity as the imago Dei, which connection this article endeavors to explicate, lest a fundamental truth should suffer neglect.

We must begin by affirming a bedrock principle of our creed: that the Lord Jesus Christ, being himself subsistent paternal light, appeared among men to reveal the Father (see, e.g., Mt. 11:27, Jn. 1:18, Heb. 1:2-3). It seems almost silly to recite this teaching. Yet sometimes we talk generally about the “incarnation of God,” emptying salvation of its proper Trinitarian dynamism. But it is the Lord Jesus Christ, and only the Lord Jesus Christ, who is the Face of God: his Son, Word, Wisdom, Power, and Radiance. Apart from him, the Father is neither understood nor recognized. Thus, we adore Christ as God’s manifest Image, in whom we “behold the unspeakable beauty of the Archetype,” namely, the Father almighty (St. Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit IX, 23).

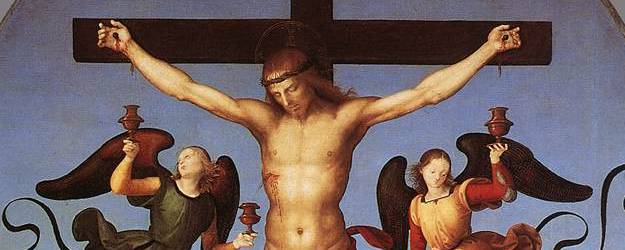

Christ undoubtedly showed himself to be the Image of God — that is, God’s faithful Expression — throughout the course of his earthly sojourn, articulating in his humanity the paternal utterance that he simply is in his divinity. Yet this mystery finds its clearest form in the cross, where Christ displayed by his profound kenosis the Father’s self-giving charity (1 Jn. 4:7–11). As Origen remarked: “We do not hesitate to say that the goodness of Christ appears in a greater and more divine light, and more according to the image of the Father, because he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death” (Commentary on John I, 37). Therefore, the cross was (and is) the fitting locus of God’s unveiling. Crucified, the Son exhibited the self-diffusive Being whence all things spring, and even now presents himself as the selfsame Reality to those who enjoy the contemplative vision of faith: “When you have lifted up the Son of Man, then you will know that I AM” (Jn. 8:28; see Ex. 3:14, Is. 41–45).

The apocalyptic quality of the cross is not a riddle reserved for theological speculation. On the contrary, it is woven into the fabric of Christian piety. Consider, for instance, how we invoke the Holy Trinity while making the sign of the cross, thereby professing the “God who was manifested by the cross” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, Against Eunomius V, 3). The sacraments likewise testify to this mystery, each in its own manner. The Eucharist in particular elucidates the inner meaning of the cross, at once proclaiming and communicating the divine agape that converted a supreme act of injustice into a supreme act of charity, and making Calvary an intelligible revelation of God’s nature.

Yet man no less than God is revealed in the cross. Indeed, man is not merely revealed, but perfected; rather, he is revealed to the extent that he is perfected. For man was made in the image of God (Gen. 1:27), and his primitive felicity consisted in bearing the glory of God through conformity to his Creator. This blessed state he forsook by turning his heart from the eternal light, so that it grew cool and dim and shadowy. Christ, by his appearance and service, restored in man the image of God, making our nature a unique vehicle for the expression of the Father’s self-diffusive love. “He commenced afresh the long line of human beings . . . so that what we had lost in Adam — namely, to be according to the image and likeness of God — that we might recover in [him]” (St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies III, 18, 1 — from the Syriac version). Through his passion, Christ wrought the paternal countenance in human shape (for the Father is generative and communicative charity), thereby making man truly to be and seem divine. Upon the sacred wood, the image of God in man again blazed forth; presently, it remains available for appropriation through the sacraments, and especially through the Eucharist, where “God’s own agape comes to us bodily” (Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est 14), and we find and become our true selves through an encounter with the true Image. Ecce homo!

The cross, in short, is a double doorway, leading into the depths of the mysteries of God and man, which mysteries cannot, after the Word’s advent, be rightly separated. Those who receive the Holy Spirit from Christ’s side apprehend the cruciform God (see Eph. 3:18–19). Insofar as they perceive God, they simultaneously grasp the enigma of the human person, who, endowed with the imago Dei, is summoned to make visible the invisible splendor of divinity, which consists firstly in love beyond telling (Eph. 3:19). If only we could maintain this vision before our eyes, we might more persuasively share the faith, showing how the cross contains every secret of existence and embraces “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col. 2:3).

Recent Comments