“I will tell of the decree of the LORD: He said to me, ‘You are my son, today I have begotten you’” (Ps 2:7). The psalmist is referring here to Israel’s anointed, or messianic, king. As God’s anointed one, he is God’s “son,” God’s earthly representative or visible image. The kings of the world are therefore obliged to heed and obey him, and thus to serve Almighty God through him (vv. 6–12). The New Testament tells us unequivocally that this concept of a divinely chosen messiah is ultimately modeled on, and supremely fulfilled in, Jesus Christ (Acts 4:26–27; 13:33; Heb 1:5; 5:5), who is begotten, according to His divinity, by God the Father as His natural Son, in the everlasting “today” of eternity: God from God, light from light.

When eternal, unbegotten Light — that is, “the Father of lights” (Jas 1:17)1 — eternally begets the Son-Light in love, the Son is identical with Him in every way according to the divine nature, while the two remain eternally distinct according to their respective personal identities as Unbegotten Begetter and Only Begotten One. “Seeing” what the Father does, the Son does likewise (Jn 5:19): He fully and forever directs His personal, divine being reciprocally back to the Father in love, thus reflecting perfectly the glorious splendor of the Father as His exact representation, or image. The divine, personal expression of this mutual love of the Father and the Son is the Holy Spirit, who proceeds eternally from them both. Together with their Spirit, the Father and the Son are eternally bound in an utterly unique, supreme, and ineffable communion of love, united consubstantially as one God.

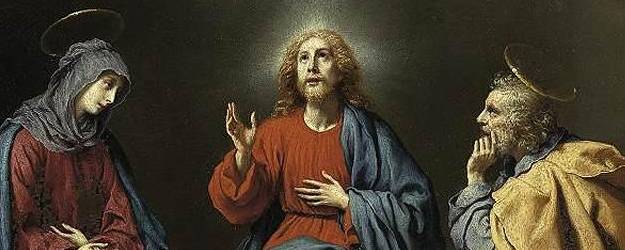

With this trinitarian foundation in mind, let us reflect briefly on three of the revelatory mysteries that we celebrate during the Christmas Season, namely, the Incarnation, the Holy Family, and the Baptism of Jesus.

The Incarnation

“Today I have begotten you”: The Father has begotten His divine and eternal Son not just in the “today” of eternity, but also on a particular “today” in time, when “the power of the Most High” overshadowed Mary of Nazareth, and she conceived that same Son as man. Since it belongs to the eternal identity of this Son to be the only begotten one, the revelation of His eternal identity to us in time, as man, fittingly required that He be the only begotten, not just of His divine Father, but also of His human mother. Mary’s Son had therefore no siblings born of her. She is the ever virgin mother of God-made-man. The mystery of the Father’s eternally begetting the Son of God both grounds, and is reflected in, the mystery of His sending us, through Mary, His Son as man — as our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, whose virginal conception and birth we celebrate at Christmastime.

Since the eternal Son of the Father and the temporally conceived Son of Mary are one and the same divine Person, it follows that Jesus Christ, the Son incarnate, would express His eternal begottenness of the Father, and His eternal, loving self-directedness to the Father, in a way corresponding (or proportioned) to the humanity He received from His mother by God’s power and her gracious consent.2 For only then would the Son express Himself, and thus reveal Himself to us, in and through His human nature according to who He really is eternally.

And so it is that Jesus’s every act of perfect obedience to the will of His heavenly Father constituted a concrete actualization, in time, of His eternal begottenness, affirming anew His eternal, filial relation of love for the Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit. In that way, Christ’s perpetual earthly obedience to the Father both reflected and revealed the Father’s ever begetting Him in the “today” of eternity. This same begetting is identical with the Father’s paternal relation of love for His only Son, in the Spirit. It grounds and reflects eternally the very Fatherhood of God the Father. Jesus expressed all this summarily in His uniquely intimate way of addressing His Father as Abba.

Though the Incarnation was brought about by all three Persons of the Holy Trinity as one God, the Letter to the Hebrews expresses it in a way that highlights the reciprocal relation of the Father and the Son: “A body [a human nature, body and soul] have you prepared for me” (Heb 10:5). By means of this body, the Son would express His filial relation to the Father through perfect obedience: “Behold, I have come to do your will” (Heb 10:7). The Father willed but one thing, toward which Jesus’s whole earthly life was directed with unwavering fidelity, namely, that through the eternal Spirit (Heb 9:14), the incarnate Son should offer His sinless humanity to the Father as a sacrifice for our sins; therefore, His offering Himself to the Father was, at the same time, an offering also for us, for our sanctification (Heb 10:9–10, 12–14). It is therefore impossible to consider the Christmas mystery of the Incarnation without anticipating the mysteries of Holy Week, and even of Easter.

We can now see more clearly that it is precisely in the saving love of the Father and the Son for us, as expressed in the Father’s sending the Son, and in the incarnate Son’s unconditional obedience to the Father even unto death, that their eternal relation of mutual love in the Spirit is simultaneously revealed to us. The Son carries out the will of the Father by making a total sacrifice of His life for our sake because He has first — indeed, eternally — offered His whole, personal being, in the love of the Spirit, to the Father, who lovingly begets Him eternally, and also temporally, sending Him forth “in the form of a servant” to save us by His atoning death (Phil 2:7–8). Thus, the mutual love of the Father and the Son contains ever within it their redemptive love for us.

Because these two loves coincide in the Person of the incarnate Son sent by the Father, the historical fulfillment of God’s redemptive love for us in Jesus’s cross and Resurrection reveals to us its source in the intratrinitarian love of the Father and the Son in the Spirit. We might regard Christ’s Resurrection as the Father’s act of reciprocating, vindicating, and confirming the incarnate Son’s unconditional love for the Father,3 as expressed in the act of His obediently taking up the cross and everything leading to it, beginning with the Incarnation. Whereas their respective acts relative to each other indicate the relative distinction of their Persons, Jesus’s claims of absolute equality with the Father (e.g., Jn 5:17–18; 8:58–59) — which imply the absolute commensurability of their mutual love, and hence the absolute unity of their salvific purpose relative to us — indicate their substantial unity according to the divinity: “I and the Father are One” (Jn 10:30).

The undying love of the Father and the Son for us is expressed in the birth of the divine baby who would grow up specifically to die, that we might live. This constitutes a revelation of the incalculable value that God has placed on each one of us. Even the bare fact of the Incarnation itself — God’s becoming man in the Person of the Son — reveals with unparalleled power and clarity just how valuable we are in the sight of God, and just how seriously He takes us for that reason. Jesus Christ was born to us, one holy night, to restore in us the divine image in which we had been created, but which we marred by sin: “Long lay the world/ in sin and error pining/ till He appeared, and the soul felt its worth.”4

We, like all things, “were created through Him and for Him” (Col 1:16). But it was specifically for our sake that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14), so as to reclaim what belongs to Him. This is what we celebrate on Christmas Day. This we ought to celebrate, in humble gratitude, every day.

The Holy Family: Finding the Child Jesus in the Temple (Gospel Reading, Year C)

When Jesus was twelve years old, Mary and Joseph took Him to Jerusalem for the feast of the Passover. As the pilgrims departed after the feast, He stayed behind in the Temple, without His parents’ knowing it: “Zeal for your house consumes me” (Ps 69:9). During the three days it took them to find Him, He listened to the rabbis, holding His own among them. Adopting a common rabbinical method of teaching and inquiry, He posed questions and answered them, exhibiting an amazing level of understanding (Lk 2:46–47).

When His anxious parents finally found Him, His mother asked Him why He had done this to them. In all innocence, He asked them, in turn, why they had been searching for Him: “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” (v. 49), as if to say, “Where else would I be? Where the Father is, there am I. Why all this needless worry?” The question Jesus posed to His parents was, in fact, a self-revelation. It seems that even after all they had seen, heard, and dreamed so far in connection with the events surrounding Jesus’s incarnation and birth, Mary and Joseph still did not yet comprehend fully His mission and divine identity. This gave Mary pause to ponder His reply in her heart (vv. 50–51). Eventually she would understand.5 The teachers of the law, in large part, would not.

Jesus’s cryptic response to His parents in the Temple indicates that He knew perfectly well that He is eternally the only begotten Son of the Father. Given that the Son’s unconditional obedience to the Father’s will is the perfect, human expression and revelation of His Person — of His eternal begottenness of, and filial love for, the Father — we can only conclude that it was the mysterious will of the Father Himself that Jesus should remain behind in the Temple and interact with the rabbis there. Expressing His natural, filial relation to His divine Father through perfect obedience to the Father’s saving will for us took precedence over all else, including His filial relationship with Mary His mother, and with Joseph her husband, the devoted guardian of both Jesus and Mary. Indeed, the Son’s filial obedience to the Father constituted His very sustenance: “My food is to do the will of Him who sent me, and to accomplish His work” (Jn 4:34). By remaining behind in the Temple, therefore, Jesus was nourishing Himself on that food. His heavenly Father would not fail to provide for Mary and Joseph in this situation, or in any other.

Then why, we might ask, did Jesus return to Nazareth with His parents when they finally found Him in the Temple? And why was He obedient to them thereafter (Lk 2:51)? Had He not been obedient to them before?

Disobedience on the part of Jesus, whether toward His heavenly Father or toward Mary and Joseph, is out of the question. He is a divine Person, the eternal Son of the Father. As such, He is impeccable, even in His human nature, which is endowed with its own intellect and will.6 It follows from Jesus’s divine identity and from the incomparably perfect way in which He expressed it humanly relative to the Father that He is infallible in His knowledge of His divine mission and of how His Father would have Him fulfill it. As He is the divine protagonist in the drama of human salvation, it could not have been otherwise.

We must therefore conclude that there was not, nor could there ever have been, any real conflict between the good that the Father willed His Son to accomplish relative to His salvific mission, and the good that the Father willed Him to accomplish relative to His parents, who were (and who are) at once beneficiaries of that mission, and preeminent participants in it. Jesus could in no way have been remiss in, or opposed to, His filial duty toward Mary and Joseph.

The reason, then, why Jesus returned to Nazareth with His parents in obedience to them is that they had undoubtedly expressed their will that He do so. In that will, He recognized the expression of His heavenly Father’s will for Him here and now. The Father would have the Son sanctify everyday family life by having Him lead an everyday family life with Mary and Joseph during His “hidden” years, in conformity with the reciprocal obligations of parents and their children entailed in the Fourth Commandment. The incomparable holiness of the Holy Family implies necessarily that its members fulfilled this Commandment perfectly, both individually and collectively, in accordance with the Father’s will and the grace of the Spirit.

Here we see, in miniature, the divine plan for our sanctification and eternal salvation: The Father sent the Son into the human family in the fullness of the Spirit so that through the sacred humanity of Christ, we might receive the sanctifying grace of the Spirit, and thus be reconciled with one another and with the Father as His adopted children. As such, we are now capable of fulfilling His will in humble obedience.

The Baptism of Jesus

John the Baptist preached repentance, and the people went out to him to be baptized in the river Jordan, confessing their sins. He was thus preparing a people well disposed for the One who, though ranking ahead of him and existing before him, would come after him (Jn 1:30). When Jesus presented Himself to John to be baptized, John sought to prevent Him, acknowledging his own need to be baptized by Jesus; however, Jesus explained that “it is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness” (Mt 3:15), meaning, “It is the will of my heavenly Father, who is now consummating His covenant with Israel (despite her own unrighteousness) in and through me.” So John relented.

When John baptized Jesus, the heavens opened, the Spirit descended on Him in the form of a dove, and the voice of the Father spoke. According to Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the Father began by declaring, “This is [or, You are] my [beloved] Son” (Mt 3:17; Mk 1:11; Lk 3:22), taken from Psalm 2:7; however, some ancient versions of Luke complete this verse, which reads (as we saw earlier) “today I have begotten you,” whereas the other two evangelists follow instead with words taken from the opening of Isaiah’s first Servant Song, which read, “with whom I am well pleased” (or, alternatively, “in whom my soul delights,” or “on whom my favor rests.” See Is 42:1).

This difference in these Gospel renderings adds significant depth to our understanding of the revelation from heaven recorded here. Both the kingly figure in Psalm 2, and the servant of God in Isaiah, are endowed with the Spirit — the king implicitly, as he is the LORD’s anointed (Ps 2:2), and the servant explicitly: “I have put my Spirit upon him” (Is 42:1). God has given his servant as a covenant to the people and a light to the nations (Is 42:6; 49:6, 8). The servant will fulfill this mission through agonizing suffering, as an offering to God for the sins of many. But God will vindicate him, and many will become righteous because of him (Is 50:5–9; 52:13–53:12).

Indeed, God will exalt him so highly that kings will be silent on his account and pay him homage (Is 52:13–15; 49:6–7). This suggests that the servant will, in the end, surpass them all in power and glory — in kingliness. It seems, then, that the suffering servant and the LORD’s anointed, the messiah-king, are one and the same person. The evangelists are telling us as much through the words of the heavenly Father at Jesus’s baptism: this suffering King is Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Savior.

The incarnate Son is the very embodiment of God’s covenant with His people, of the “marriage” of God and man. His obedience to the Father’s will in being baptized by John fulfills the very righteousness, or holy fidelity, of God. For in and through the Son, on whom the Spirit has come to rest, the Father is fulfilling the covenant with Israel by which He will redeem her and make her His own. The Son’s unfailing fidelity to the Father — itself an expression of God’s fidelity to us — compensates superabundantly for Israel’s history of covenantal infidelity.

Given that when the Father sends forth His word, it achieves unfailingly the end for which He sent it (see Is 55:10–11), the earthly actions of Jesus, the Word of God, were always efficacious, and never merely symbolic. It seems reasonable to suppose, then, that the Father had the Son, Himself free of all sin, undergo John’s baptism of repentance because this would be the means by which Christ would publicly and formally take our sins on Himself as our Head and as our Mediator before God the Father. As such, He alone could offer the Father a perfect act of repentance for all human sin on our behalf.7 This was a decisive step toward His making possible the actual forgiveness of our sins by water and the Spirit in Christian baptism, as opposed to John’s merely symbolic cleansing of repentant sinners with water alone, which served to prepare the way for the baptismal regeneration in the Spirit that Christ would bring.8

We can surmise that the Father accepted the Son’s act of repentance for our sins because the Son, ever obedient, always does what is pleasing to the Father (Jn 8:29), who is therefore “well pleased” with Him and always hears Him (Jn 11:42). Jesus’s baptism thus signified His perfect filial love for the Father, whose voice from heaven revealed, in the “today” of time, His ever begetting the Son in the “today” of eternity.

Again, supposing that the Son took on our sins at His baptism and repented of them fully on our behalf, the Father willed, nevertheless, that the Son should offer additionally an expiatory act of reparation for them: the Lamb of God had yet to take away the sin of the world (Jn 1:29).9 His “anointing” by the Spirit, at His baptism, revealed publicly that the humanity of Christ was “confirmed” in the fullness of grace necessary to realize this act of expiation, in gracious obedience to the Father’s saving will. Hence, the baptism of Jesus inaugurated the public ministry that would lead Him, inexorably, to the cross. It represents the pivotal point in the providential progression from Christmas Day toward Holy Week, from the Son’s Incarnation and birth toward His Passion.

By the atoning sacrifice of His own life for our transgressions, Jesus would justify many; that is, He would make righteous before God all those who are willing to accept the grace that He merited for everyone, thus restoring them to the dignity, lost by our first parents in the beginning, of being adopted children of God. At the same time, His agony — the agony of God — on the cross would expose the vile and violently evil nature of our sins, and their injustice to God above all, while also revealing the necessity, in justice, of their being expiated, if we are ever to be restored to friendship with God.

Since all the attributes we ascribe to God separately are really one and the same in Him, the cross of Christ, which divine justice demanded because of our sins, constitutes and reveals, at the same time, the overflowing mercy that the Father extends to us through His innocent Son. In perfect obedience to the Father, Our Lord was willing to endure the cross — an incomparable injustice against Him — in place of, and for the sake of, the guilty, the ones deserving punishment, death, and the torment of eternal separation from God, that is, the second death (Rv 20:14; 21:8). We sinners, mercifully spared in this way, would consequently gain, through the superabundant merits of Christ, the divine offer of forgiveness for our sins. And through the grace of forgiveness received, we would gain as well the grace of becoming partakers in the divine life.

By our accepting the transformative grace that Jesus won for us through His perfect obedience to the Father even unto death, He is “begotten” in us, such that we may call His Father our Father. Through the Son and in the Spirit, we must therefore express our filial love for the Father by living a life of humble, uncompromising obedience to His saving will, beginning with its most fundamental expression in the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes, without whose observance we cannot actualize the law of love. This restoration to life in the Spirit is precisely what the Father has willed to accomplish in us by sending us His obedient Son, born for us in Bethlehem, and born in us through the sacraments, each in its own way, beginning with baptism. So, when the Son reveals Himself, His Father, and their Spirit anew to us each Christmas, He means thereby also to reveal to us who we can be, and who we ought to be, by the grace of adoption into the trinitarian family of God.

- The lights to which James is alluding here probably designate the created lights of the material world, such as the sun, the moon, and the stars. But of itself, the term “light” extends analogically to include also the spiritual hosts of heaven, created as “angels of light” (2 Cor 11:14). Far more so than earthly realities, the angels correspond to, and so reflect more perfectly, the luminous truth, goodness, and glory of God, who “dwells in unapproachable light” (1 Tm 6:16), without any shadow of darkness (1 Jn 1:5). Biblical revelation and the development of trinitarian doctrine bequeathed to us by Catholic Tradition show us that the analogy extends still further, giving us some insight about the Supreme Reality that explains the origin and existence of all these created lights. The uncreated Word of God, through whom the Father made all things (Jn 1:1–3; Col 1:16), is the eternal “Light from Light.” Every created being reflects this Light, however faintly, in the truth and goodness that it radiates through its specific nature. The Son-Light generated eternally by the “Father of lights” is the same Light that came into the world to enlighten every human being (Jn 1:9; 8:12), so that no one need ever be overcome by the darkness of sin, falsehood, death, or the devil (Jn 1:5). That is why to have this Light is to have life eternal, and vice versa (Jn 1:4; 8:12). ↩

- Mary’s body provided the physical substance of Christ’s human nature, whereas the Holy Trinity created the human soul of Christ at the moment of the Son’s incarnation, at which time it was united to the biological component to form His humanity. ↩

- When viewing Jesus’s resurrection from the standpoint of His strictly human powers, the New Testament ascribes it solely to the action of the Father (e.g., Acts 2:24); however, both Christ’s resurrection and the resurrection of those who have died in Him is a work of the Holy Trinity (as indicated in Jn 10:17–18 and Rom 8:11, which attest to the action of the divine Son and the Holy Spirit respectively in raising the dead). ↩

- From the Christmas hymn O Holy Night. ↩

- Mary’s deeper understanding is evident in the faith she placed in her Son during the wedding feast at Cana. When she saw that the supply of wine had been exhausted, she said to the servants, “Do whatever He tells you” (Jn 2:5). She left entirely to Him exactly what to do, but she knew that He could do something to save the situation. She seems also to have known that His action, whatever it might be, would hasten the arrival of His climactic “hour” (v. 4). And if she understood the import of that hour, then it is likely that she also understood that the intervention she sought from her Son would hasten as well the arrival of her unique role, at that same hour, as the “woman” (Jn 2:4; 19:26), as the new Eve. She would henceforth be the Mother of the Church (Jn 19:27), who would give birth to children of God through the pain of her maternal suffering (united completely with the excruciating suffering of her Son) at the foot of the cross, thus fulfilling Simeon’s prophecy (Lk 2:33–35). This would mean that by the time she attended the wedding feast at Cana, Mary, in total union with the saving will of the Father and the Son by the grace of the Spirit, was prepared to offer her Son in sacrifice for the world’s redemption — to give away the Bridegroom to the Bride, as it were — in anticipation of the marriage of the Lamb (Rv 19:7), the beginning of which she would attend at Calvary. ↩

- Human obedience to proper authority presupposes a rational understanding of the nature of the good commanded by that authority, along with the will to accomplish this good freely, insofar as it accords with right reason and falls within the scope of the power entrusted to the authority. Disobedience to a legitimate law or command issued by a proper authority suggests a defect in the understanding or the will. Jesus had no such defects. His human will was always perfectly submissive to what He knew, infallibly, to be the divine will (see Mk 14:36; the Council of Constantinople III, 681; Catechism of the Catholic Church, §475), which He possessed fully with the Father and the Holy Spirit in His divine nature. At the Incarnation, Christ’s two natures — divine and human — were ineffably united in His divine Person (the Hypostatic Union), such that the manner in which He acted through them, according to the mode of operation proper to each, could never have resulted in a conflict between them. ↩

- Analogously, during Mass on the first Sunday of Lent in March 2000, Pope John Paul II, as the visible head of the pilgrim Church, expressed repentance publicly for the sins of all her members throughout the centuries. He was beseeching God’s forgiveness, so that the Church could begin the new millennium with a purified conscience, and thus carry out the New Evangelization in a fitting and effective way. ↩

- Note that what I am suggesting here takes nothing away from the more mystical theology of the Eastern Church Fathers, which regards Jesus’s baptism in the Jordan as the occasion when Our Lord sanctified the waters of the earth in anticipation of Christian baptism. Note, too, that contrary to the more recent contention that Jesus was merely expressing solidarity with sinners symbolically in being baptized by John, the sinless Son of God spent His public ministry, rather, calling sinners to solidarity with Himself, through the forgiveness of their sins and through their sanctification in the Spirit — beginning with baptism — that they might enter the Kingdom of God through the Son, in whose name the Father would send the Spirit (Jn 14:26). ↩

- Here we see an analogy with the sacrament of reconciliation, in which, even after having expressed our repentance and received absolution for our sins, we must nevertheless perform acts of penance in order to expiate any temporal punishment still due to sin. On the one hand, Christ’s perfect act of repentance for our sins at His baptism (which I have proposed herein as a reasonable supposition), together with His atoning sacrifice for them on the cross, has gained for us the grace to repent sincerely of our sins out of filial love for God, rather than out of a servile fear of retribution only. On the other hand, it seems that we are likely to respond to this grace only partially, given our need to do penance for sins already confessed and forgiven. Still, God does not withhold His forgiveness from us, nor reconciliation with Himself, when the contrition we express in the confessional is not motivated solely by our love for Him, and hence is not fully informed by the ardent charity that His grace makes possible. It follows, therefore, that Christ’s vicarious repentance and expiation for our sins nevertheless compensates superabundantly for our failing in this regard. ↩

Recent Comments