Saint Mary Magdalene: Prophetess of Eucharistic Love by Fr. Sean Davidson (Ignatius Press, 2017). Reviewed by Rev. John P. Cush, STD.

And Mary’s ‘Yes’ Continues. By the Dominican Sisters of Mary, Mother of the Eucharist, under the direction of Sr. Joseph Andrew Bogdanowicz, OP, Co-foundress and Vocations Director (Ann Arbor: Lumen Ecclesiae Press, 2017) 340 pages. Reviewed by Fr. Thomas Hoisington.

Fulfilled in Christ. The Sacraments: A Guide to Symbols and Types in the Bible and Tradition. By Fr. Devin Roza. (Steubenville: Emmaus Academic, 2015). Reviewed by Sean P. Robertson.

Astrophysics and Creation: Perceiving the Universe through Science and Participation by Arnold Benz (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2017) 144 pages. Reviewed by Dr. Michael Gouge.

The Light Shines on in the Darkness (Transforming Suffering through Faith). Robert Spitzer, S.J., Ph.D. Ignatius Press: San Francisco. 2017. ISBN 978-1-58617-957-1. 543pp. (paper) $19.95. Reviewed by Clara Sarrocco.

In Missouri’s Wilds: St. Mary’s of the Barrens and the American Catholic Church, 1818 to 2016, by Richard J. Janet (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2017). 288 pages, $24.95. Reviewed by Dr. Wilburn (Bill) T. Stancil.

Awakening Love, An Ignatian Retreat With the Song of Songs. By Gregory Cleveland, OMV (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2017). Reviewed by Rev. Andreas Hoeck, S.S.D.

______________

Saint Mary Magdalene: Prophetess of Eucharistic Love by Fr. Sean Davidson (Ignatius Press, 2017). Reviewed by Rev. John P. Cush, STD.

This certainly is the year for Saint Mary Magdalene in the world. In the secular world, the actress, Rooney Mara, plays the penitent saint in an eponymous film this year, and singer, Sara Bareilles, has recently portrayed the apostle to the Apostles in a live television version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar. Liturgically, the Magdalene was raised to the level of a feast day in 2016, with her own proper preface to the Eucharistic Prayer of Mass. Rarely has there been a better time for a book which can help the English-speaking world to know and appreciate this great woman of faith, and saint of our Church. As the author points out, there is much literature written in French on the Saint, but very little translated into English. Fr. Sean Davidson, a priest of the Missionaries of the Most Holy Eucharist, who had been assigned to serve at the Basilica of St. Mary Magdalene in Provence, France, has done a great service with his well-written, well-researched, highly spiritual book.

Fr. Davidson handles well the question, biblically and historically, of exactly who the Magdalene actually was. By turning to the long-standing tradition of the Church, he points out that, in our Roman Catholic Tradition, it was always understood that Mary Magdalene was Mary, the sister of Lazarus and was also the woman who washed the feet of the Lord Jesus. Fr. Davidson rightly points out that the universal acceptance in our Latin Church of the Magdalene as the same woman in these accounts was verified by Fathers of the Church like Saint Augustine of Hippo and Pope Saint Gregory the Great. This understanding of these three biblical figures as one and the same woman was also believed by saints, like John Fisher and Thomas More, as well as the Doctor Communis, St. Thomas Aquinas. Fr. Davidson wisely acknowledges that Anglo-Saxon exegesis, particularly in North America, has been influenced in large part by feminist currents of thought which sought to make the apostle to the Apostles as a patroness of female ordination. Fr. Davidson writes: “The idea of Mary at once being a public sinner with a tainted reputation, and then later becoming a deeply contemplative soul, inclined more to silence than to making herself heard in the crowd, did not fit with the vision of her being a liberated woman, in the modern sense of the word, involved in power struggles with the apostles. Through writing, teaching, and lecturing, some feminist scholars countered the Church’s veneration of Mary as the model of penitents and contemplatives.” (23)

Fr. Davidson posits that Mary was the woman from whom the Lord drove out seven demons, and that she was the sister of Lazarus and Martha, who had, perhaps, been a courtesan in the household of Herod (hence her friendship with Joanna, the wife of Herod’s steward, Chuza). It is this Mary who had encountered the Christ, and began to cling to him, to repent, and follow him. Fr. Davidson demonstrates the rich, beautiful spiritual implications of her conversion. It is she who was the sinful woman of Luke 7, and it is Mary of Magdala who is the woman who does “something beautiful” for God (Mt 26:10). The author, by a careful study of the Saint as the woman who becomes the “perfect image of the New Eve” (chapter 3) by welcoming Jesus the guest into her home, receiving him “under her roof,” teaches us the proper way to encounter Christ in Holy Communion and in Eucharistic Adoration. The Magdalene becomes our example of how to live when we, like Martha, are “distracted from much serving,” and simply need to be with the Lord in adoration. Fr. Davidson gives us a model of Mary: as living in hope of the resurrection in the death of Lazarus (chapter 4); and, in her anointing of Christ, becomes the recipient of untold graces (chapter 5); and demonstrates that it is the Magdalene who is the “first consoler of Jesus and Mary” (chapter 6). The author powerfully reminds us: “What the Church needs today above all, if we are to make up for the unceasing torrent of sacrileges and outrages that flood the sanctuary, are souls who know how to gaze like Magdalene into the eyes of the eucharistic Jesus,” (177).

This text, highly engaging and highly readable, offers a fresh look, one that takes into consideration solid scriptural exegesis, as well as the tradition of the Latin Church, into one of the most inspiring of all the saints. The author shows us the way to be “apostolic” in our reception of Holy Communion, and to be inspired by the Eucharist in fully engaging in the proper attitude of prayer taught clearly by the Catechism of the Catholic Church: gratitude, contrition, adoration, and love. Fr. Davidson has produced a beautiful testimony to one of the most misunderstood, yet greatest saints of our Church, the Magdalene. It is highly recommended.

Rev. John P. Cush is a priest of the Diocese of Brooklyn. He serves as Academic Dean and as a formation advisor at the Pontifical North American College, Vatican City-State. Fr. Cush holds the Doctorate in Sacred Theology (STD) from the Pontifical Gregorian University, where he also teaches as an adjunct professor of Theology and U.S. Catholic Church History.

_______________

And Mary’s ‘Yes’ Continues. By the Dominican Sisters of Mary, Mother of the Eucharist, under the direction of Sr. Joseph Andrew Bogdanowicz, OP, Co-foundress and Vocations Director (Ann Arbor: Lumen Ecclesiae Press, 2017) 340 pages. Reviewed by Fr. Thomas Hoisington.

The staggering decline in vocations to the consecrated life has signaled that not all of the changes made in the Church over the past fifty years have been in accord with Scripture and Tradition. Both the Church, and the world that she serves through spiritual and corporal works of mercy, have weakened because of that staggering decline. The contributions of the Church to health care ministry and education have necessarily fallen off without vital numbers of consecrated religious to work alongside laypersons.

Yet more serious, if less tangible, is the decline in the prayers that fewer consecrated religious can offer for the Church and the world. Recently in the news, we read about the closure of Himmelrod Abbey in Germany, whose consecrated religious had, since A.D. 1134, offered prayers to God’s glory, and for the good of the Church and the world. If this closure were an anomaly, it would be less disturbing.

Nonetheless, as disheartening as these facts are, they’re made worse by a peculiarly modern form of spiritual myopia. This lack of sight afflicts many of the religious orders whose numbers have sharply declined over the past five decades. Although the link between certain changes of the past fifty years and declining numbers is clear, myopia prevents such religious orders from reversing the decline.

What a breath of fresh air, then, to read And Mary’s ‘Yes’ Continues. It offers clear witness to the vitality that lies at the heart of the Church’s mission to serve God and man precisely in terms of her identity as the Bride of Christ.

Published by the Dominican Sisters of Mary, Mother of the Eucharist, whose motherhouse is found in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the Diocese of Lansing, the book consists of nineteen chapters. Seventeen are written by individual Sisters, all of whom, except one, are Dominicans. The latter two chapters present an overview of the order, and a brief prayer primer, and are followed by a glossary to help those unfamiliar with religious life.

The seventeen chapters written by individual Sisters fall into three sections: Foundations, Lived Experiences, and From the Heart of the Church. The first section concerns principles involved in discernment, entering an order, and beginning to live within that order. For example, the first chapter is titled “That Nagging Feeling: Religious Vocations in the Third Millennium”. This chapter describes challenges that most any young person today, having been surrounded for years by the messages of Western secularism, faces in trying to discern a life founded upon the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The subtitles of the other chapters in this section convey the principles illustrated, including the themes of theology and religious life, philosophy of religious life, statistics on religious life, the charism of a religious order, formation in the novitiate, and personal formation for the apostolate.

The chapters of And Mary’s ‘Yes’ Continues are to a significant degree anecdotal. Much of the book’s charm flows from this approach. The authors relate experiences of discernment and entrance into religious life: both their own, and those of others they’ve met along the path of life. These anecdotes help the reader see how real the struggles are that young people face. Likewise, the anecdotes illustrate the principles that the authors want to show as foundational, keeping these principles from seeming merely abstract and impersonal.

The second section, Lived Experiences, consists of nine chapters. As its title suggests, this section is more experiential, relating the variety of backgrounds from which young women approach discernment. If the chapters of the first section are like sitting in a convent parlor on a Sunday afternoon and visiting, discussing the outlines of religious life; then the chapters of this second section are like visits in the same parlor earlier in the afternoon with young religious who tell us of their lives before entering the order. Chapters’ subtitles here include “From Homeschooling to Convent”, “The Convent after Harvard”, “Life beyond Three Car Dealerships” and “From Convert to Convent”. The latter two chapters in this section deal with the “lived experiences” of Sisters teaching in elementary schools, and pursuing post-graduate studies while serving in campus ministry.

While this book largely reflects upon principles and experiences of religious life from the perspective of Dominican Sisters, references to other religious orders are made. In Chapter 5, subtitled “Living the Charism of a Religious Order or Community,” the notion of a charism, and the way it shapes the living of religious life, is described, and specific charisms, such as those of the Benedictines, Carmelites, and Franciscans, are discussed. Also, Chapter Seventeen in the book’s brief third section is written by a Carmelite Sister from England who reflects upon the nature of joy in religious life.

In this collection of personal accounts, the authors show us how young persons today can find not just personal fulfillment, but the Person of Christ: the One who has called them into relationship with Him, in both loving prayer, and a loving apostolate.

Fr. Thomas Hoisington was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Wichita in 1995. He earned a Licentiate in Sacred Theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome in 2001, with an emphasis in Dogmatic Theology. He posts scriptural reflections at: ReflectionsOnTheSacredLiturgy.com.

_________________

Fulfilled in Christ. The Sacraments: A Guide to Symbols and Types in the Bible and Tradition. By Fr. Devin Roza. (Steubenville: Emmaus Academic, 2015). Reviewed by Sean P. Robertson.

In Fulfilled in Christ, Fr. Devin Roza gives us a very useful tool for deepening our understanding of the seven sacraments, especially as found in the unity of Scripture, and the theological tradition of the Church. This volume is a comprehensive guide in which we find compiled numerous symbols and types for each sacrament. Within each symbol or type listed, we are provided a detailed list of Scriptural references, from both the Old and New Testaments, where that particular symbol is used. Accompanying this, Fr. Roza has also compiled the most important references to these symbols in the Catechism, the Fathers of the Church, and the sacred liturgy (limited in this volume to the Roman Rite, for the sake of concision). In this way, we can more easily come to understand the sacraments, both in their original Scriptural context and background, as well as the tradition of their interpretation in the Church, in her teaching and her prayer.

As Scott Hahn points out in the foreword, this volume comes at an important time, because it is a helpful contribution to the renewal of mystagogical catechesis which is so greatly needed in our time. It presents us with a means of delving into the mystery of the sacraments, and thus of understanding more thoroughly the plan of salvation which God has designed for the Church. Understanding the spiritual meanings of the sacraments through their types and symbols leads us to understand better what is accomplished in us when we receive them, and thus allows us to participate more fully in the mysteries of the Church’s liturgical life. Fulfilled in Christ is an important aid for one seeking to understand these mysteries.

In his introduction, Fr. Roza explains the importance of typology and symbolism in Sacred Scripture, and why we should be interested in it today. As he notes, the tradition of interpreting Scripture typologically goes back not only to the Fathers of the Church, but it is also present within Scripture itself. It is clear, he says, that the New Testament authors interpret the events of the Old Testament as prefiguring those of the New, events which find their fullest meaning in the coming of Christ. The words of Christ Himself show that He understood His actions to be the fulfillment of those of the Old Testament. This way of understanding Scripture, Fr. Roza says, is not limited to the early Church, but has been a constant part of the Church’s scriptural exegesis even up to the present day, as witnessed by the explanation of the fourfold sense of Scripture in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Nonetheless, he points out, many modern biblical exegetes have moved away from this method of understanding God’s Word, because they perceive it as subjective and unscientific. In response to this, Fr. Roza proposes reading Scripture in the living tradition of the Church, as Vatican II recommends, and this requires a recovery of the spiritual senses of Scripture which have been so important in the life of the Church through the centuries. It is precisely this recovery of the spiritual senses of Scripture that this book, Fulfilled in Christ, successfully aims at facilitating.

Fr. Roza also clarifies his understanding of the difference between types and symbols in Scripture, which is important for understanding how this guide works. “Typology” he defines as “the discernment of realities, events, deeds, words, symbols, or signs in the Bible that foreshadow the fulfillment of God’s plan in Jesus Christ.” (23) Meanwhile, a symbol is “an image or thing that stands for something else, and that conveys more than its literal meaning.” (30) He notes that types and symbols are often hard to distinguish in Scripture, and indeed, there is overlap between them. For the purposes of the guide, Fr. Roza types are those realities in Scripture which are taken to prefigure the sacraments, whereas symbols are those which can be used to help illuminate our understanding of the sacraments, but are not necessarily types of the sacraments in the strict sense. For example, the Crossing of the Red Sea is a type of Baptism, whereas references to washing or to rebirth are taken as symbols of Baptism. Likewise, the multiplication of loaves by Christ is taken as a type of the Eucharist, whereas references to banquets are taken as symbols of the Eucharist.

The guide itself can seem overwhelming at first glance, because of the plethora of information and references offered for each sacrament. A few uses of the guide, however, prove it to be easy and intuitive to use. Its breadth and depth allow it easily to be of use to both the academic theologian, and the average faithful. Likewise, it is an excellent resource for priests preparing homilies on Scripture or the sacraments, as well as for those providing religious education. Indeed, this volume is of great value for all seeking to enter more fully into the Word of God, guided by the Tradition of the Church, and to understand the seven sacraments more deeply.

Sean P. Robertson is a doctoral student in systematic theology at Ave Maria University in Florida.

____________

Astrophysics and Creation: Perceiving the Universe through Science and Participation by Arnold Benz (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2017) 144 pages. Reviewed by Dr. Michael Gouge.

This book begins with an excellent survey of astrophysics early in the 21st century, especially in chapters 1-6. Part I covers formation of the universe. Part II is titled “Dissolution and Horror” and Part III is “Interpretation as Creation”. The author is Dr. Arnold O. Benz who is Emeritus Professor at the Institute for Astronomy, ETH, Zurich, Switzerland. The chapters dealing with perception and interpretation are not as well developed as the balance of the book.

Prof. Benz writes in the abstract of a 2017 journal article (Zygon, vol. 52, no. 1, 186-195) summarizing the contents of this book:

I explore how the notion of divine creation could be made understandable in a worldview dominated by empirical science. The crucial question concerns the empirical basis of belief in creation. Astronomical observations have changed our worldview in an exemplary manner. I show by an example from imaginative literature that human beings can perceive stars by means other than astronomical observation. This alternative mode may be described as “participatory perception,” in which a human experiences the world not by objectifying separation as in science, but by personal involvement. I relate such perceptions to “embodied cognitive science,” a topical interdisciplinary field of research in philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. Embodied cognitions initiate processes that can convey personal experiences of the stars. Such cognitions may involve religious apprehensions and give rise to sophisticated values. It is argued that the knowledge available through astrophysics and interpretation of the universe as divine creation represent two different ways of perceiving the same reality and should thus be seen as mutually complementary.

While “participatory perceptions”such as awe in stargazing as a youth (in the Prologue), or apprecating a poem by Walt Whitman (pages 52-53) may get one interested in plasma astrophysics, or even spark a vocation, real progress needs more and more powerful computers and digital cameras, better models as well as additional satellites.

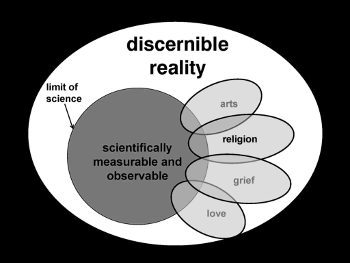

This compact book is loaded with 21 digital figures of objects in the Universe including: galaxies, nebulas, clouds, stars, supernovas, planets, asteroids, and craters. There are two other figures, one showing a timeline for events in the universe—from the past, the Big Bang (13.8 billion years ago), and the future—see figure 12. The other, figure 14, shows a hand-drawn “schemetic of human perception of reality” which is shown below:

Figure 14 from Benz.

Before discussing details of figure 14, I show below another perception of reality.

Non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA), for example,

by Stephen Jay Gould.

This latter NOMA model seems to me and, apparently to Prof. Benz also, to be too constricting. What comes to mind is the image of the mother in 2 Maccabees telling her son: “So I urge you, my child, to look at the sky and the earth. Consider everything you see there, and realize that God made it all from nothing, just as he made the human race.” (2 Macc 7:28). Surely the mother’s insight into Creatio ex nihilo would qualify for a bit of common ground from these otherwise isolated circles.

Prof. Benz should consider the overlapping areas for arts, religion, grief, and love in his figure 14, and give concrete examples of where, for instance, a perception overlaps between science and art. Perhaps a sculpture of a galaxy could give insight to three spatial dimensions that a painting or screen projection could not. For a living example, consider the Belgian astronomer Georges Lemaître and how perceptions of him as priest and scientist impacted the 20th century development of the Big Bang creation model of the universe.

Dr. Michael Gouge is a Deacon in the Diocese of Knoxville, TN.

_____________

The Light Shines on in the Darkness (Transforming Suffering through Faith). Robert Spitzer, S.J., Ph.D. Ignatius Press: San Francisco. 2017. ISBN 978-1-58617-957-1. 543pp. (paper) $19.95. Reviewed by Clara Sarrocco.

In the Gospel of St. Matthew, it is written: “Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” (Mt 6:34). In his book, The Light Shines on in the Darkness, volume four of the quartet, Father Spitzer takes on the problem of human suffering, and how it can be requited by an all-loving God. He proceeds to lead the reader on a journey, difficult as it may be, to realize that suffering can bring us closer to God, and to greater empathy with suffering humanity.

The book is divided into three “phases.” In Phase One, entitled “The Theological Preparation for Suffering,” Spitzer considers the “rational belief in the resurrection, and the unconditional love of God.” He does this by defining the prevalent false notions of God that cloud man’s judgment, such as the “angry God,’ the “payback God,” the “domineering God,” the “terrifying God”, the “stoic God”, and the “disgusted God.” These distorted ideas prevent us from believing in God’s goodness, and keep us from realizing the importance of knowing that God is present to us through it all. His advice is to avoid unjustified accusations against God’s justice, love, and compassion, and to assume a posture of humility before His invitation to draw us closer to Him. Just as we would like to have the benefit of the doubt given to us, it is important to give God the same opportunity. By the use of rationality, and an act of the will, and prayer, we can come to accept—”Blessed are the sorrowing, for they shall be comforted” (Mt 5:4).

Phase Two: “Contending with Suffering in the Short Term” guides the reader on what to do when things seem bleakest. He recommends spontaneous prayer for help in learning how to use the suffering for a good end. It will require transforming the suffering from a negative experience to one of growth in virtue. Putting it all in God’s hands, and knowing that He will be there to understand and give consolation, is of primary importance in mitigating anxiety, and in learning to become free in accepting His love. It is important to realize that the focus should not be on getting immediate relief, but on hoping that good will come of both physical and spiritual pain.

Phase Three: “Benefitting from Suffering in the Long Term” is the longest and, perhaps, the most profound of the sections. In it, Spitzer wants the reader to be wary of the pitfalls that could exacerbate suffering. It is important to be in touch with the teachings of Jesus, and the power of the Holy Spirit, to guide and comfort. Imitating Jesus’ self-sacrifice in suffering for our sins will help in bringing us closer to acceptance and, eventually, lead to a richer life, and happiness in the Kingdom. He briefly reviews the four levels of happiness from physical-material desires, to an ego-comparative advantage, to altruism, and finally to the wish to be in a relationship with God. In his desire to bring the reader to a fuller comprehension of what it means to love, Spitzer describes the four kinds of love as written by C.S. Lewis in his book, The Four Loves. They are Storge or affection, Philia or friendship, Eros or romantic and exclusive love, and finally Agapē or selfless love. To further illustrate the importance of these distinctions, Spitzer includes a brief biography of some saints who have given witness to exceptional love in their lives. He mentions St. Francis of Assisi, St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Peter Claver, St. Théresè of Lisieux, and St. Teresa of Calcutta (Mother Teresa), among others. It is their mystical self-offering that gives to the rest of us meaning to our suffering and our hope.

After giving all his advice on how to face suffering, Father Spitzer ends this section with: “A Vexing Question and a Synopsis of the Relationship among Suffering, Freedom, Love and God.” After all the analysis, what it comes down to is that suffering is part of the human condition and how we understand it is what matters. We are not self-sufficient, and we have to come to the realization that God does not create suffering, but does give us gifts to help in the time of pain, and the opportunity for a more profound existence. In his “Conclusion” Father writes:

There is light in the darkness—the light of salvation, love, freedom and transcendence, and personal actualization. The darkness, through faith, makes this light all the more profound and precious, refining our freedom and love to an ever greater, authentic, purified, and unconditional state.

Because of the profundity and universality of the topic of suffering as the human condition, Father Spitzer has promised another volume on the topic of evil, virtue, and faith. We can look forward to: Called out of the Darkness: Contending with Evil, through Virtue and Prayer.”

The Light Shines on in the Darkness is an important book because who among us has not tasted the bitterness of suffering, of whatever kind, and wondered how to relate it to believing in the goodness of God. Father Spitzer not only gives a thorough logical and philosophical approach to understanding human suffering and the mercy of God in man’s darkest hours, but he brings to the reader his own experience with tragedy. Father Spitzer is blind, and so what he gives to us is not simply theoretical knowledge, but a personal story from his very heart. In the words of Pascal: “We know truth, not only by reason, but also by the heart.” Each book in Father Spitzer’s quartet, the other three being—Finding True Happiness, God So Loved the World, and The Souls Upward Yearning—can be read separately, but taken together, they resemble a musical composition, which once combined, form a symphony.

Clara Sarrocco is the longtime secretary of The New York C.S. Lewis Society. Her articles and reviews have appeared in Touchstone, New Oxford Review, Gilbert, The Chesterton Review, CSL: The Bulletin of The New York C.S. Lewis Society, St. Austin’s Review, The International Philosophical Quarterly, The Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Quarterly, Homiletic and Pastoral Review and the Catholic Historical Encyclopedia. She has taught classes on C.S. Lewis at the Institute for Religious Studies at St. Joseph’s Seminary, and is the president of the Long Island Chapter of The University Faculty for life.

________________

In Missouri’s Wilds: St. Mary’s of the Barrens and the American Catholic Church, 1818 to 2016, by Richard J. Janet (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2017). 288 pages, $24.95. Reviewed by Dr. Wilburn (Bill) T. Stancil.

Richard Janet (Ph.D., University of Notre Dame) is a professor of history at Rockhurst University in Kansas City, Missouri, where he has taught since 1985. Janet’s interest in St. Mary’s of the Barrens is both professional and personal. He writes with the keen eye of a historian but also with the affectionate heart of one whose own personal history is rooted in the geography of southeast Missouri and St. Mary’s, where he taught history from 1982-1985. Those two orientations—the professional and the personal—serve Janet well. The story he chronicles of St. Mary’s turns out to be a microcosm of the story of the American Catholic Church.

Following a taxonomy suggested by historian Philip Gleason, Janet divides the history of St. Mary’s into three eras: an era of boundlessness in which innovation and adaptation are prominent (1818-1847), an era of fragmentation and consolidation in which the institution overcomes threats and stabilizes (1847-1888), and finally the post-Civil War revival of St. Mary’s, followed by its decline and closing (1888-1962). As suggested in the subtitle of the book, these eras describe both the history of St. Mary’s and trends in the American Catholic Church.

Founded in 1818 in present-day Perryville, Missouri, St. Mary’s of the Barrens was the first American institution of higher learning west of the Mississippi River and the fourth Catholic seminary founded in the American Catholic Church. The “Barrens,” as it was called, was the motherhouse of the Congregation of the Mission, better known as the Vincentians. Located far from the eastern seaboard cities, the rural location of the Barrens in southeast Missouri belied its influence in training leaders for the American Catholic Church.

The story of St. Mary’s begins with the diocese of Louisiana, which stretched across the vast geographical territory of the Louisiana Purchase. When Bishop Louis William DuBourg decided to move the episcopal residence from New Orleans to St. Louis, the Barrens became the focal point for theological education, in spite of its remote location. St. Mary’s was a dual seminary, training candidates for the diocesan priesthood and candidates for the Vincentian order. The school also operated a lay college for boarders, a day school for locals, a farm, and a parish on the seminary grounds.

The early Vincentians at St. Mary’s were forced to make a number of adaptations to American culture that were foreign to their European sensibilities. They struggled with a harsh environment, treacherous travel, a new language, a frontier culture, Protestant bigotry, and chronic financial difficulties. These challenges and others were met with innovation and hard work. For example, the opening of a lay college alongside the seminary, a financial boon but also a means for evangelization, was untraditional in is mingling of lay collegians with diocesan seminarians and Vincentian candidates. The operation of a farm on the seminary grounds provided income and food. At one point the St. Mary’s Vincentians owned slaves, though the lack of an official Catholic position on slavery contributed to the moral ambiguity felt by these Vincentians living in Missouri, a border state.

By 1862 all seminarians, diocesan and Vincentian, had left the Barrens, leaving only the lay college. An 1866 fire sealed the fate of the lay college. It too left the Barrens and moved to Cape Girardeau, reducing the Barrens to a day school. Not until some 25 years later did the revival of the Barrens take place when the Vincentians divided the province and the Barrens became the central house for the Western Province. This period—from 1888 to 1962—was a time of growth and revival for the Barrens. Seminary training for Vincentian candidates returned to the campus.. Reflecting trends in American Catholic higher education, academic and formation programs became more rigorous. New building were erected, and a host of auxiliary enterprises were established, the most prominent being the Miraculous Medal Association, which to this day still operates at the Barrens with a fulltime staff of fifty-six workers.

The post-World War II period until the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) was the golden era for the Barrens. As the cultural assimilation of American Catholics accelerated, St. Mary’s also became more engage in conforming to the new demands of educational institutions, especially institutional accreditation. Curriculum review and revision, faculty development, library holdings, financial stability, administrative organization, and a host of other concerns related to higher education became the focus of several self-studies conducted at the Barrens, resulting in formal accreditation in 1967 by North Central Association. The impact of the Barrens in this time-frame is attested to by the host of influential scholars, teachers, and church leaders who spent time at St. Mary’s as students and/or faculty.

As bishops gathered in Rome in the fall of 1962 for the opening of the twenty-first Ecumenical Council (Vatican II), few could have predicted the changes that were on the horizon for the Roman Catholic Church. Those changes, and other factors, led to the closing of the Barrens in 1985. The challenges of a modern world for religious orders, declining vocations, the Vincentian decision to pull back on its seminary commitments, a movement in American Catholic education to close free-standing college seminaries, the cost of maintaining outdated buildings, the isolation of Perryville from the larger pockets of Catholics—all of these and other factors contributed to the final closing of the Barrens in 1985. What remains of the Barrens today is a retirement center, a farm, the historic Church of the Assumption with its National Shrine of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, a visitor center, and the offices of the Association of the Miraculous Medal. Additionally, there is a Catholic Home Study Service operating and a local community college offers courses in one of the refurbished buildings on campus.

What we learn from the story of St. Mary’s of the Barrens, Janet believes, is not only the necessity for change and adaptation, but the importance of adhering to an essential mission in the midst of those changes. And through it all, we must maintain historical memory.

In Missouri’s Wilds is a compelling book for a number of reasons. First, it’s the kind of regional history that needs to be told but often goes untold for lack of publishing resources. Truman State University Press is to be commended for their American Midwest series and for the excellent editorial work and the inclusion of twenty-four photos in the book. Additionally, In Missouri’s Wilds can be read on two levels. On the one hand, it’s the story of one institution and the circumstances surrounding its founding, growth, and decline. On the other hand, because this one institution is embedded in several additional institutions—the Roman Catholic Church, the American Catholic Church, and the Vincentian Order, the influence and challenges from these other entities makes the story of St. Mary’s much more intriguing. If “no man is an island” as Donne once wrote, it’s also true that no institution exists without a number of other factors that inevitably contribute to its failure or success.

Finally, In Missouri’s Wilds demonstrates that one of life’s greatest motivators is dedication to a cause that is rooted in a spiritual commitment. One cannot read this book without being impressed by the tireless labor and selfless service these Vincentians gave to carry forward their mission. Even as the painful decision was made to close St. Mary’s, the deep love for the old seminary was obvious for those who had passed through its doors.

In Missouri’s Wilds deserves a wide readership. The research is solid, the writing lively, and the story of St Mary’s of the Barrens engaging, especially as it intersects with the story of Catholicism in America. Janet has preserved an important piece of American Vincentian history.

Wilburn (Bill) T. Stancil is Professor of Theology & Religious Studies at Rockhurst University, Kansas City, MO (bill.stancil@rockhurst.edu).

_________________

Awakening Love, An Ignatian Retreat With the Song of Songs. By Gregory Cleveland, OMV (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2017). Reviewed by Rev. Andreas Hoeck, S.S.D.

Father Greg Cleveland in his book “Awakening Love, An Ignatian Retreat With the Song of Songs” combines in an original and resourceful way two texts that have a vastly different literary background: He takes the Old Testament Wisdom book of the Song of Songs and interprets it in light of the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola. The result is a unique and useful tool for laity and clergy alike, to be drawn deeper into the mystical world of biblical prayer, guided by Ignatian methodicalness and purpose.

The thirty-two chapters of the book are systematically introduced by a thematic quotation from the Song of Songs and from the Spiritual Exercises, followed by a reflection in which the author exegetes both passages by relating them to one another. His meditations strike a happy balance between a thoughtful pondering of the scriptural passage and a prayerful application of Ignatian principles of spirituality. This flow of insights is infused with everyday experiences of prayer, sin and virtue, the desire to grow and remain in a loving relationship with God. A variety of patristic and modern authors are cited to enrich the illustrations, to exemplify a case in point, and thereby making the interior movements of the human soul come to life for the reader. Each chapter is then concluded by a succinct questionnaire for personal reflection or communal discussion, as well as a number of prayer suggestions to aid in internalizing the message proposed. Finally, in the Appendix of the book one can find a Table of Themes that summarizes the correlation between the Canticle of Canticles and the Spiritual Exercises for all thirty two chapters.

Among the greatest strengths of Fr. Cleveland’s book is his ability to employ the Word of God in explaining the profound mysteries of the human heart, to come to better terms with the dynamic and logic of divine grace. Scriptural passages almost effortlessly accomplish the goal of shedding light even into the recesses of the soul, describing the movements of consolation and desolation. In this way, the author covers the entire eight chapters of the Song of Songs in juxtaposition to the Ignatian four weeks of exercises.

In going about unearthing the spiritual depth of those texts, fitting recourse is had to the allegorical value of those scriptural images. As an example, the “foxes” in Ct 2:15-17 are understood as representing our evil tendencies toward sin, ultimately aimed at destroying the “vineyard” of our souls. Metaphorically, those foxes must be controlled by watchfulness over our outer and inner senses, in order to maintain inner peace and well-being. This spiritual sense of the Bible is then coordinated with the second week of the Ignatian Exercises, where the Saint is calling for a regular examination of conscience, involving steps like gratitude, petition for light, reviewing the day, forgiveness and amendment. Also applied are the rules for discernment of the spirits, since the foxes equally represent deception and falsehood. Again, the mystical reading of the biblical image leads to a deeper understanding of the seriousness of our Christian commitment in withstanding Satan’s attempts to ruin the Lord’s work in our lives and in the Church.

Of course, the overarching image that sustains the book’s spiritual trajectory is that of the two lovers, or of the bride and bridegroom, in the vicissitudes of their relationship. Fr. Cleveland inserts himself into the mainstream of Christian tradition when he again detects in them the love between Christ and the individual soul. What is so felicitous about comparing Ignatius’ teaching with the Canticle is the circumstance that in both texts we find an emphasis on the inner feelings and thought processes that can be monitored and should be evaluated for sound spiritual discernment eventuating in the spiritual realities of faith, hope and love, peace and joy.

Plentiful are also the scriptural references in the Prayer Exercises at the end of each chapter. The reader is encouraged to use specific passages to pray with them in view of enlightenment and steady guidance in the path of perfection.

Another forte of this book is the presence of numerous anecdotes and stories that powerfully enliven the narrative, and facilitate the grasp of the otherwise rather elusive subject matter of the work of God’s grace in us. Finally, and besides the very uplifting and encouraging language throughout, the reader is given freedom to either spend a consistent amount of time to journey through the entire course of chapters, or to stay and rest with one or the other of them, delving deeper into and resting with the movements of light and grace whenever and wherever they occur. In addition, therefore, to the solid integrity and cohesion of the many chapters, each one of them can serve as a precious incentive to more seriously seek the face of God.

Thus, may Fr. Cleveland’s book “Awakening Love” be for many a “lamp to the feet and a light to the path” (Psalm 119:105) of the Christian calling to that nuptial union between the soul and its divine Bridegroom, Jesus.

Fr. Andreas Hoeck is a Professor of Theology at Saint John Vianney Theological Seminary in the Archdiocese of Denver.

Recent Comments