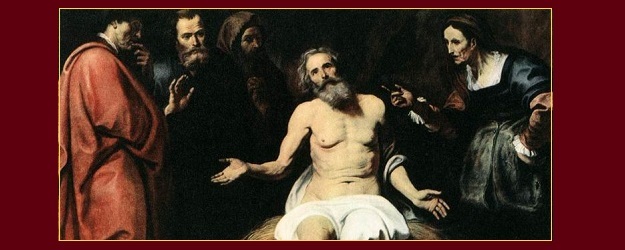

The Patient Job by Gerard Seghers (1591-1651)

Question: Can you explain to me the problem of evil exemplified in the Book of Job?

Answer: In answer to your question, I would like to summarize the Commentary on the Book of Job by Thomas Aquinas, which I have recently translated. As many modern scholars are puzzled by what is taught there, the opinion of Thomas Aquinas is just as good as any modern exegete, and needs to be better known.

St. Thomas comments on the Book of Job because he thinks it addresses an extremely important problem in divine providence which is the prosperity of the wicked, and the suffering of the just. How could a good and reasonable God allow this to happen? In his commentary, Aquinas also points out that the problem is set up by the accusation of Satan, that Job does not fear God from a right intention. Satan accuses Job of making God a means to an earthly end: the physical health and material prosperity of Job. Since God is infinite and the creation finite, God cannot be a means to an end, but all must end in Him. Furthermore, the problem of the suffering of the just is complicated by the reaction of Job to his suffering. He so laments the day of his birth, that he wishes he had been an aborted fetus. For Christians, this seemed an inhuman and unworthy attitude. They were influenced in some ways by Stoical philosophy which taught that the just never experienced strong passions, especially sorrow. Indeed, the passions were the enemies of virtue. As a result, the commentary of Aquinas is the first attempt in the history of the Church to write a commentary on the literal sense of the book.

The solution of St. Thomas is interesting because unlike many modern commentators, he finds an intense unity of thought in the book. The chapters which express Job’s lament involve Job speaking about the issue of the suffering of the just from the point of view of the passions. This will have important implications for the same problem in the life of Christ. The second part of the book, which is the long dispute of Job with his friends, examines the same issue from the standpoint of reason. The final section, which entails God revealing the answer as the arbiter of the dispute, is the discussion of the same issue from the point of view of divine revelation and faith.

When Job laments the day of his birth, he is expressing a great truth of human nature, that a just man can experience great suffering from the point of view of his passions. It would be inhuman to suppress sorrow, and pretend it does not exist in the face of all the things Job has suffered. He has what Aristotle called “moderate passions”. In fact, virtue produces moderate passions. The word “moderate” here does not refer to intensity but the governing of the passions by reason. Though Job suffers intensely, he does not curse the day of his birth. He thus preserves the order of reason, even in the face of this intensely emotional reaction.

When the discussion moves to reasoned argument, the friends affirm the point of view present at the time, that physical suffering and loss must be a punishment for personal sin. Job defends himself by maintaining that reason teaches that nothing physical can be the final purpose of man, who has a spiritual soul. He goes so far as to affirm the resurrection of the dead as the proper reward for human life, together with the vision of God. The truth that the vision of God is the purpose of human life is easily drawn if one affirms the presence of the intellect in man. To attain this vision would, however, entail faith and grace. The resurrection is, of course, a miracle, so this would depend on faith. If such is the case, the experience of physical suffering or pleasure is no proper criterion for the state of a person’s soul.

The point is finally clarified by God, who condemns the friends for false teaching, and judges Job guilty, not of error in his teaching, but rather of venial sin in immoderate speech before God, which could lead others to scandal.

The conclusion of the book is that physical loss, of whatever kind, is a human evil, but not the greatest human evil. This would be the loss of heaven. If God permits the wicked to prosper, this is from his patience and mercy. Because they set their final purpose and, thus, their hope in materialism, they would despair altogether if they lost material prosperity. On the other hand, God permits the just to suffer because their hope is in Him, and in heaven. The fact that Job experiences this hope defeats Satan, and proves to Satan, to the friends and to Job himself, that he fears God for a right intention. This gives further glory to God.

____________

Question: Can you evaluate the admonition by Cardinal Sarah explaining that the proper way to receive communion is kneeling?

Answer: The issue of the proper posture for receiving Holy Communion has long been a subject of discussion and controversy. For example, when Archbishop Cranmer was reforming the Church of England, the subject came up in the second edition of the Book of Common Prayer. The other Protestant reformers wanted the posture to conform to the posture of the Apostles during the Last Supper to affirm Scripture, and to deny Transubstantiation. Cranmer did not want to be seen trying to change the doctrine of the Church, so he short-circuited this attempt by explaining to the King’s Council, which approved such decisions, that this would entail lying on the floor, or on couches. Needless to say, the prospect appalled them. By the time they decided to preserve the custom of kneeling, the rubrics for the liturgical book had already been printed in red. Rather than try to print the rubric for kneeling in red, this rubric was thus added during the black printing of the book, so it is called the “black rubric.” Kneeling was preserved as implying reverence and humility for a gift, but as the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer makes clear: “… yet, lest the same kneeling should by any persons either out of ignorance and infirmity, or out of malice and obstinacy, be misconstrued and depraved: It is hereby declared, that thereby no Adoration is intended, or ought to be done, either unto the Sacramental Bread and Wine there bodily received, or unto any Corporal Presence of Christ’s natural Flesh and Blood.” (BCP, 1662: Declaration of Kneeling).

Kneeling was traditional in the Latin Church for many centuries. But this issue became urgent in the Catholic Church as a result of the permission to receive communion in the hand. Many bishop’s conferences stated that the only proper way to receive communion in the hand was standing, which was a sign of the resurrection. As a result, to preserve uniformity, it became customary to stand for communion in most Catholic parishes.

The practice of kneeling for communion dates from the Middle Ages, with the clarification of the nature of the Eucharist. Kneeling was traditional in the Latin Church, but not in the Eastern Church. As the Latin Church defined the Eucharist as Transubstantiation, kneeling became a posture which expressed the adoration of the elements. This is not to dismiss the practice of standing in the Eastern Church, but simply to point out that the Latin Church more clearly defined the nature of the Real Presence, and developed a different external way of demonstrating this. What appears as bread and wine truly IS the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. In the 1960s, the practice of kneeling began slowly to change. Communion rails were removed, and some priests and bishops even went so far as to refuse communion to anyone who knelt to receive the sacrament.

As a part of his “reform of the reform,” Pope Benedict blessed the practice, at the Vatican, of kneeling when he distributed Holy Communion. Pope Francis has clarified that the use of this term can be misleading if one thinks more changes in the liturgy are planned. Pope Benedict had something else in mind, which was an attempt to emphasize words and gestures permitted in the present rite which could clearly underline the supernatural character of the liturgy. As one of these gestures, Pope Benedict authorized kneeling for communion at the Vatican for those chosen to receive communion from him. Cardinal Sarah is just continuing this attempt to return to implementing a deeper reverence and faith in the Blessed Sacrament. On July 5, 2016, he gave a conference in London in which he, as the head of the congregation responsible for divine worship, worried that Catholics had lost faith in the Real Presence, and encouraged the practice of kneeling at Mass as an attempt to recover it: “Kneeling at the consecration (unless I am sick) is essential. In the West, this is an act of bodily adoration that humbles us before our Lord and God. It is itself an act of prayer. Where kneeling and genuflection have disappeared from the liturgy, they need to be restored, in particular for our reception of our Blessed Lord in Holy Communion.” This is not, of course, to contend that mere exterior gestures guarantee devotion. For one who is unable to genuflect, there is not necessarily any lack of interior devotion. In the same way, someone who genuflects without reverence may betray a mere formalism. All the same, one of the exterior acts of the virtue of religion is adoration, and all things being equal, interior devotion should be expressed in exterior actions since we have bodies. Cardinal Sarah wished this to be implemented by the first Sunday of Advent in 2016.

Of course, when the Vatican reacted officially to his talk, it was clear that he himself has no authority to make such a change, and no new norms are being planned or implemented. Disunity is not a good thing, and while appreciating the need to express needed reverence and devotion, whether standing or kneeling, must always be the prime purpose of any emphasis on a devotional practice in the liturgy. Cardinal Sarah does demonstrate a needed corrective to an attitude of almost persecuting some Catholics who wish to kneel to receive communion. He also issues a call to examine how a custom may have influenced some of the problems (John Paul II called them “shadows”) in the implementation of liturgical renewal. At the very least, this should alleviate Catholics having to defend their choice to kneel for Holy Communion, and the unfortunate tendency of some pastors to deny communion to people who do so. At most, it should be a clarion call to express true internal devotion in either standing, or kneeling.

Recent Comments