For Sunday Liturgies and Feasts

Homilies for April 2014

Fifth Sunday of Lent – April 6, 2014

Martha’s Grief and True Hope

Purpose: The Lenten readings summon us to experience a foretaste of Christian hope in the raising of Lazarus from the dead. In our society, hope in the resurrection and eternal life needs to be distinguished from the purely secular hopes which are often offered as substitutes for it.

Readings: Ezechiel 37:12-14; Psalm 130:1-8; Romans 8:8-11; John 11:1-45

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/040614.cfm

One Lenten Sunday, I was seated in the congregation of a prominent Jesuit church. The preacher announced that the theme of his homily was Christian hope. He informed us that “true Christian hope is the belief that tomorrow will always be more beautiful than today.” With this Hallmark Hall of Cards opening, the priest then explained that Christians are always optimistic (real “can-doers”), never wear a frown, and know how to turn the proverbial lemon into lemonade. “Hopeful people are never down.”

Father’s gushing sermon perfectly expressed the perennial American gospel of the power of positive thinking, but it was a counterfeit of Christian hope. Today’s gospel on the raising of Lazarus presents a portrait of authentic Christian hope, complete with the tears and the fear which accompany even the most loving disciple.

The opening of the gospel is remarkable for its realistic presentation of the grief of Martha. She is stunned by the death of her brother Lazarus, probably a young man who died a rapid death. She is not only in grief, she is angered that Jesus did not come more quickly to prevent Lazarus from dying. “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” St. John repeatedly underlines the particular love which Jesus had toward the siblings Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. The Benedictine liturgical calendar has a beautiful feast dedicated to this mystery: Saints Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, friends of the Lord.

When Jesus encounters Martha in her sorrow, he leads her to authentic faith and hope. He asks her two questions. “Martha, do you believe that your brother will rise?” Martha responds that she does believe that her brother will rise from the dead on the last day. The response of Martha is typical for a pious Jew of the period. There is some sort of personal survival from death, and there is some sort of day of judgment at the end of time for the living and the dead. But the terms of this hope remain vague and impersonal. Jesus then asks her the question of faith. “Martha, do you believe that I am the resurrection and the eternal life you are looking for? Do you believe that in and through me you will have this life beyond death you yearn for?” It is only then that Martha makes her act of faith as disciple. She acclaims Christ as the Son of God, come into the world to redeem it from sin. The hope for eternal life for the just is no longer vague or only philosophical. It is now a matter of Christ’s resurrection and the disciple’s belief in it.

The encounter with Martha still confronts the contemporary world. When Christ asks the first question about life after death, the vast majority of Americans will still answer in the affirmative. There is something beyond death, and it has something to do with the moral choices we make in this life. But this hope is vague, with God the Judge often reduced to a sentimental easy grader. Christ urgently asks us the second question. Do we believe that in him we find the resurrection from the dead that only God in his mercy can grant? Do we believe that in the risen Christ we see our own ultimate future in communion with God through God’s freely given grace, and our own freely given cooperation?

It is this question, and the living response in Jesus Christ, that guides us to the heart of authentic Christian hope. It is a hope which no political committee, no therapeutic technique, and no exercise in positive thinking can give us. It is the hope of freedom from sin and death which is the gift outright in the passion and resurrection of Christ.

The risen Lazarus confirms the truth, contradicting all biology, and all logic: that in Christ God’s power can conquer even death. Of course, Lazarus will die again in several years. He only points weakly to the conquest of death in Christ which will know no further death. He points to the glory of Christ risen forever, and embodies the authentic Christian hope that the faithful disciple will one day share the glory beyond the tomb and beyond our deepest grief.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Catechism of the Catholic Church §381-387.

______________

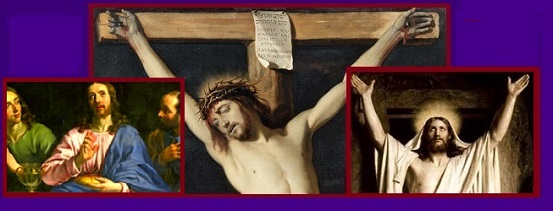

Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion – April 13, 2014

The Palm, the Cross, and the Coward

Purpose: Palm Sunday is the moment to acclaim the glory of Christ as he enters Jerusalem, and to commiserate with Christ as his glory unfolds in the ignominy of the cross. The Passion reveals the depth of God’s mercy, and of our own sinfulness. In our own times, cowardice is an especially strong manifestation of that sin, waiting to be redeemed.

Readings: Matthew 21:1-11; Isaiah 50:4-7; Ps 22: 8-24; Philippian 2:6-11; Mathew 26:14-27:66.

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/041314.cfm

Inaugurating Holy Week, today’s solemnity of Palm Sunday is a diptych. The opening part of the liturgy shows the glory of God in the person of Christ, the king and messiah. The palm-bearing crowd acclaims the triumphant Christ entering Jerusalem, with the gestures of praise, awe, and adoration. Our church’s procession with ministers robed in red and gold, with the choir leading us in “All Glory, Praise, and Honor,” and with the congregation moving through the fresh spring air as they bear palms, re-enacts that moment of acclaim to Christ, the glorious king. But as we enter into the Eucharist itself, the tone changes. Christ is now Isaiah’s man of sorrows. There is no beauty in him. The Passion according to Saint Matthew carves out the humiliation of Christ: the beatings, the unfair trials, the suffering and death on the cross, the betrayal and abandonment by the apostles.

As St. Matthew details the chapters of Christ’s passion, he unveils the particular sins which lead to Christ’s death on the cross. Judas is stung by greed. “They paid him thirty pieces of silver, and from that time on, he looked for an opportunity to hand him over.” The scribes and Pharisees are clearly afraid of a religious rival. “Then the high priest tore his robes and said, ‘He has blasphemed! What further need have we of witnesses?” Simple sloth causes the disciples of Jesus to abandon him during the agony in the garden of Gethsemane. “So you could not watch with me for an hour? Watch and pray that you may undergo the test. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.”

It is striking how prominently cowardice figures into the outbreaks of sinfulness which leads Christ to his death on the cross. Always moved by the pressure of public opinion and sudden swings in emotion, the mob, which had once acclaimed Christ with the palm of kingship, now turns against him. In the arrest of Jesus, the crowd abandons its earlier support for Jesus. “Have you once come against a robber, with swords and clubs to seize me? Day after day, I sat teaching in the temple area, yet you did not arrest me.” During the trial before Pilate, the mob becomes even more craven. It offers no explanation why it prefers Barrabas to Christ. It simply shouts repeatedly, “Crucify him! Crucify him!” St. Matthew indicates that the mob has surrendered to the pressure from the priests and scribes opposed to Jesus.

Cowardice drives two of the major characters of the Passion: Pilate and St. Peter. Pilate knows that Jesus is innocent of the charges against him. Both his own interrogation of Jesus, and the urgent message from his wife, have reinforced this conviction. But he refuses to render a just verdict because of his fear of the mob. “When Pilate saw that … a riot was breaking out, he took water and washed his hands in the sight of the crowd, saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood.’”

St. Peter’s cowardice is almost comical in its manifestation. It is not a mob or a powerful group of clerics which pressures him to betray Christ and falsely claim that “I do not know the man.” It was a simple question posed by a servant girl. But fear of persecution had gripped him as he three times denies any knowledge of, let alone discipleship of, Jesus of Nazareth.

Even in his depiction of the few disciples who remained faithful to Christ on the cross, St. Matthew suggests how the fear, and temptation to cowardice, gripped this tiny remnant. As with the other evangelists, St. Matthew underlines the fidelity of the women who followed Christ. But unlike much Christian iconography of the Passion, he does not place these women at the foot of the cross. He places them at a distance from Golgotha. “There were many women there, looking on from a distance, who had followed Jesus from Galilee, ministering to him. Among them were Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee.” Even for the few who remained faithful in the shadow of the cross, the courage is touched by fear.

Focusing on the cowardice which colors the sin driving Jesus to death on the cross can help the ministers and assembly on Palm Sunday to face our own temptations to cowardice. Our society applauds those who cut corners on their marital vows, their taxes, or the promises they made to those they serve. It mocks those who adhere to the Gospel in their sexual and economic lives. The temptation to refuse to witness to one’s faith, and to act according to a well-formed conscience, is a temptation to cowardice for us all. It is not only a danger for individuals. It is a temptation for the Church herself, as she is increasingly pressured by the state and public opinion to be silent on the great moral questions of human life and human love. The iniquity of cowardice unveiled by the tragedy of the crucifixion of Jesus is as summons for all of us, as individuals and as a community, to speak and act in the truth, even when such a choice requires a courage that will give us a taste of the folly of the cross.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Catechism of the Catholic Church §130-137.

_____________

Holy Thursday: Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper – April 17, 2014

Watching and Waiting with Christ

Purpose: Holy Thursday is a glorious celebration of two great gifts Christ has granted his Church: the gift of himself in the Eucharist, and the gift of the new priesthood he has instituted. But this glory is not that of the world. It is rooted in a mission of humble service, and it manifests itself in the loneliness of Gethsemane, and the suffering of Golgotha.

Readings: Exodus 12:1-14; Psalm 116:12-18; 1 Corinthians 11:23-25; John 13:1-15

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/041714-evening-mass.cfm

Holy Thursday has always had a magical quality to it. During my suburban childhood in the 1950s, we would visit three different churches after we had attended the solemn celebration of the Lord’s Supper in our own. We would kneel before the Blessed Sacrament surrounded by flowers, brocades, silk canopies, and candles―in one neighboring church, a waterfall with colored strobe lights―on the altar of reposition. Prayer would become a pilgrimage in the night, and a moment of mystical fellowship with neighboring Catholics in our county. Later in the evening, men from the Holy Name Society would break their sleep, late in the evening, and walk through the dark streets to spend an hour of silent meditation before the Blessed Sacrament as members of an honor guard.

The evening’s liturgy is almost unbearably rich, as we are moved by the Spirit from one mystery of faith, and one spiritual mood to another. The evening Mass begins in glory as the bells are rung during a rousing “Gloria” after a long gilded procession of ministers down the aisle. But, then the organ is suddenly silenced for the rest of the Triduum. By the end of the liturgy, we are stripping the altars of its cloths and ornament. We enter the dark silence of Gethsemane. The apostles fled on that first vigil of the Passion. We have heard the call to “watch and wait” in fidelity to Christ’s call to be with him as he faces the cross.

The truths we celebrate this evening lie at the heart of the Catholic faith. As St. Paul indicates in the epistle, we celebrate the gift of the Eucharist, of Christ himself present body and blood, divinity and humanity, to his Church until the end of time. “On the night he was handed over, the Lord Jesus took bread and, after he had given thanks, broke it and said, ‘Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also after supper, he took the cup and said, “This cup is the covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink of it, in remembrance of me.’” In celebrating the institution of the Eucharist, we also celebrate the institution of the priesthood in Christ, the community of the apostles, and the successors called to preside over the Eucharist, during the Church’s pilgrimage toward eternity, and to preach God’s redeeming Word from the heart of the Eucharist.

St. John’s Gospel points to a different part of the mystery we celebrate this evening: our humble service of each other in Christ’s charity. In the moving ceremony of Christ’s mandatum, we wash the feet of the poor, the elderly, and the sickly as an expression of the spiritual service upon which the entire life of the Church is based. “If I, therefore, the master and the teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet. I have given you a model to follow. As I have done for you, you should also do for each other.” In centering the church on this mystery of humble, loving service, no contemporary Christian has been more forceful than Pope Francis has been in his simple words and gestures of solidarity with the disabled. As Holy Thursday moves toward the mystery of the agony in the garden, the trials, and the crucifixion, the cost of this loving service in Christ, becomes clearer and clearer. In the shadow of Gethsemane, the church’s own call to suffer for the sake of the truth in her service emerges.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Catechism of the Catholic Church §284-304

____________

The Resurrection of the Lord ― the Mass of Easter Sunday ― April 20, 2014

Easter Glory: Before and After

Purpose: At Easter we celebrate the central mystery of the faith: the Resurrection of Our Lord from the dead. The Scripture readings for Easter point to the transformation which the first apostles, and the entire Church, must undergo in the light of the Resurrection.

Readings: Acts 10:34-43; Psalm 118: 1-23; Victimae Paschal Laudes; Colossians 3:1-4; John 20:1-9

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/042014.cfm

With her dramatic genius, the Church sets the celebration of Easter in a visual and audial setting of life overcoming death. As spring yields to a harsh and snowbound winter, the breezes and flowers and longer days witness to the perennial triumph of light over darkness. The stripped altar, and empty sanctuary of Good Friday, surrenders to gold vestments, sprays of flowers, clouds of incense and repeated “Alleluias.” Trumpets and drums join the unsilenced organ to lead the assembly’s joyful noise, replacing the sober silence of Lent. Even the commercial frills of the season, such as the Easter egg in a million Easter morning baskets, point to a bursting fertility and upsurge of life that goes far beyond the norm.

But all the sights and sounds are mere background for the truth we celebrate at Easter: that Our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, has risen from the dead, and that in his resurrection, we reach the heart of Christian faith and Christian hope. The Scripture readings appointed for Easter Sunday provide a before-and-after picture of this truth, as we view the disciples’ first recognition of this truth, and then see how they were transformed by the truth of this glory, and by the presence of the risen Lord in his Church.

St. John shows us the first glimpse of the resurrection on the first Easter morning. The first sign is the empty tomb. Mary Magdalene discovers that the heavy stone has been removed from the tomb. She is only confused that the Lord’s body has been moved. St. John takes a closer look, and sees that burial cloths remain in the tomb, but not Jesus himself. St. Peter penetrates into the tomb, and notices how the various burial cloths have been stored, but finds no trace of the body of Jesus himself. The puzzling empty tomb is only the first step in recognizing the resurrection of Christ. “They did not yet understand the Scripture that he (Jesus) had to rise from the dead.” As the disciples personally encounter the risen Christ in subsequent days, they hear the testimony of others who have seen and heard him, and they ponder the Scriptures more deeply on this humanly inexplicable event—the glory of Christ risen becomes the center of their lives, and of their mission to proclaim the Gospel, and build the Church.

The Acts of the Apostles provide a portrait of the disciples transformed by Christ risen from the dead, and by the Holy Spirit dwelling within them. The confused have become wise. The cowardly, once quaking behind bolted doors, have become courageous. St. Peter boldly announces the Gospel. The resurrection is the centerpiece of the good news. “This man (Jesus) God raised on the third day, and granted that he be visible, not to all people, but to us, the witnesses chosen by God in advance, who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead.” Peter not only announces Christ, dead and risen, to free us from sin; he announces the shape of the Church at its birth. The apostles, and their successors, have a special role in announcing and interpreting the Gospel to the world. Christ will be met in the Eucharist, and not only in personal prayer. The Church will minister “forgiveness of sins through his (Christ’s) name” as we await the Lord’s return “as judge of the living and the dead.”

The mystery we celebrate today is something far greater than the natural exuberance of spring, gardens, and fertility. It is the astonishing truth that Jesus Christ has conquered death forever, in his own person; and, that he offers the Resurrection as a gift outright to those who hear and keep his word—as a disciple in this life, and as a saint in the next. The signs of this Easter faith in our life go beyond the new dress, or suit, we wear, or the gold baskets that await us on the dining room table. It is found in our serious Church life, as we attend the Eucharist to “break the bread” of the Lord’s Passover, in our fidelity to the apostolic teaching of the Church on matters of faith and morals, in our joyous proclamation of the Gospel to a skeptical age, and in the giving and receiving of forgiveness through the power of the Holy Spirit.

Suggestions for Further Reading: Catechism of the Catholic Church §140-145.

___________

Second Sunday of Easter ― Sunday of Divine Mercy ― April 27, 2014

Christian Peace and the New Skepticism

Purpose: The peace announced by Christ in his Resurrection appearances is not the peace of the world: a simple absence of conflict. It is peace rooted in faith in Christ, especially his triumph over death, and a peace rooted in the forgiveness of sin by Christ through his Church.

Readings: Acts 2:42-47; Psalm 118:2-24; 1 Peter: 3-9; John 20:19-31

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/042714.cfm

In the post-Vatican II liturgical reforms, one forgotten gesture was revived. It was the kiss of peace. Before receiving Communion, members of the assembly turn to each other and wish each other the peace of Christ. The Eucharist, faith, and Christian fellowship are somehow tied to peace. In many churches, a large book is prominently set aside so that parishioners and visitors may write down their prayer petitions. Many of the petitions concern personal problems: illness, financial issues, family disputes, the sadness over a child who has abandoned the practice of the faith. But one social petition is written down, again and again: the desire for peace in the world.

The desire for peace is omnipresent. When Christ stands in the midst of the apostles in the Resurrection appearances detailed in St. John’s Gospel today, he also focuses on peace. His repeated salutation is “Peace be with you!” But the peace Christ proclaims and offers is quite different from the peace of the world. It is a peace rooted in forgiveness from sin, and in faith in himself.

First, Christ stresses that he brings the peace that forgives sin, and that reconciles the alienated with God the Father. He goes further. He makes the apostles the ministers of this ministry of reconciliation. “He breathed on them, and said to them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them, and whose sins you retain are retained.’” The sacrament of reconciliation, and the distinctive mission of the apostles, and their successors, as ministers of that sacrament have been inaugurated. One of the great marks of Christian peace will be the experience of the forgiveness of one’s sins, through the mediation of the Church. And one of the great tasks of the Christian life will be to share that mercy with others, through heartfelt forgiveness of those who have transgressed against us.

Second, in his encounter with the doubting St. Thomas, Christ emphasizes that peace is tied to faith in Christ himself, especially the truth concerning his Resurrection. The recognition that Christ is truly “my Lord and my God” grants us a peace which no therapeutic technique, and no social reform, can grant. It is the peace that flows from knowing that Christ has overcome every force of oppression—including death itself—which we face in our stormy individual and ecclesial pilgrimage. It is this daring hope which permits us to place our failure and sufferings in hopeful context, because Jesus, truly risen from the dead, has the last say in our lives, and in the history of our tormented world.

This Octave of Easter, with this figure of the doubting Thomas, could be an excellent occasion to challenge the new spirit of skepticism gripping American culture. All of us have on-the-ground experience of the rise of the “Nones”—the army of young adults who belong to no religious denomination, and have no particular religious convictions. Few of our parishioners may have read “The New Atheists,” but they are well aware of the arguments through a hundred television programs. They are bombarded by thousands of bloggers and columnists who claim that, in a new battle between science and religion, religious believers come off as the fool. A homily at the Eucharist provides little time to do more than raise the subject. A good adult-ed program could address these issues in greater detail. But, if we are to pass on the peace of Christ, we are summoned to point to the truth of God’s existence, of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, and of the divine founding of the Church as a place of sacramental reconciliation. Any new evangelization clearly requires that we respond to the arguments supporting this new skepticism.

Suggestions for Further Readings: Catechism of the Catholic Church §21-50.

Recent Comments