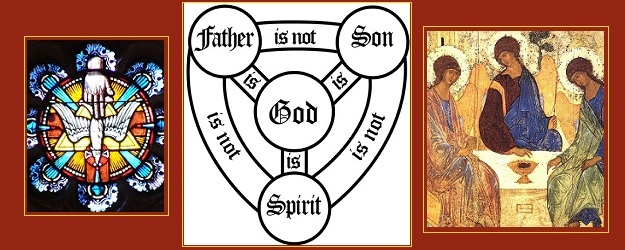

Symbols for the Blessed Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit

The scorn with which the new atheists heap on religion is understandable when one looks into their understanding of theology. The religion they reject is the religion of kindergarteners. There exists a Santa Claus that delivers presents at Christmas, an Easter Bunny who brings candy, a Tooth Fairy that takes their teeth, and a God who hears their prayers. In time, that child loses her innocence and discovers there is no Santa, Easter Bunny, or Tooth Fairy. Now the new atheists would like that adult child to do without God, too. Hence, they argue that believing in God makes about as much sense as believing in the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

I suggest that the surprising influence of the new atheists on younger Catholics comes from inadequacies in their education. If we had an educated Church, the arguments of the new atheists would inspire peals of laughter. Instead, they sadly inspire confusion.

Consider how religious art depicts God the Father. He appears regularly as an old man with a beard, alongside Jesus, and a bird. Now, no one would be tempted to think the Holy Spirit is really a bird, but I think people are tempted to think of the Father as a bearded old fogey, sort of like Zeus. Reclaiming the truth about the Father will do quite a bit toward inoculating Catholics from the silliness of the new atheists. The truth is that God is pure spirit.

Debunking the Notion

Why might we think of God the Father as a man with a beard? I can think of three reasons. First, human beings are created in the image and likeness of God; this might be taken to suggest, conversely, that God looks like us (or at least some of us). Think of Michelangelo’s powerful image that depicts God as an old man with a flowing beard just about to give the spark of life to Adam. Second, Jesus Christ presents himself as the image of the Father. Now Jesus is a man. This might be taken to suggest that God the Father looks like a man. Third, the very term “Father,” correlated as it is with the term “Son,” suggests an aged male. These three reasons, I submit, fail for the same reason: they overlook the fact that God is spirit. He is not a bodily being, and so he cannot be, or look like, an old man—with or without a beard.

We are created in God’s image and likeness. What is distinctive about the human being, in contrast to all other animals, is precisely our spiritual natures, the fact that we can know truth, will the good, and be awestruck by beauty. We are not just physical beings, but spiritual ones, as well. That we are created in the image and likeness of God above all applies to our spiritual natures. Consequently, to reverse the flow of the analogy, we can say that God is like us in that he is spirit. Pope Benedict remarks:

I believe it is important always to remember that for biblical belief it has always been perfectly clear that God is nether male nor female, but is, precisely, God, and that both man and woman are in his image.

Jesus Christ is not the image of the Father in the way that any man is an image of his human father. He is the image of the Father principally as the eternal Word. Since that is who he is, his assumed human nature can effectively reveal the Father. Again, this does not come simply from staring at Christ’s human body, but by contemplating his body together with his words and deeds. For it is in such action that the Son makes the Father palpable and understandable. Jesus is not just a snapshot of the Father, he is the streaming video of the Father. The liturgy, and the priest’s depiction of Christ, is the best image of the Father we have this side of heaven.

The Son invites us to address the Father as “father” with a profoundly spiritual meaning. Pope Benedict sees two things at work in this image. First, in contrast to pagan divinity-couples, the one God intends for Israel, and the Church, to be his bride: “In that way, the female image is given forever to Israel, and likewise to the church, and finally it is made personal and concrete yet again, in a special way, in Mary.” The Fatherhood of God corresponds to the mystery of our election. Second, the image of father better presents the truth that God is the separate providential origin of all things. God creates outside rather than inside himself, and the act of creation is appropriated most to the Father. The distinction involved in creation sets up the great story of salvation history in which God calls the creature to himself in love.

Reclaiming Spirit

God’s spiritual nature is directly related to the claim that God is the creator of all things, space and time included. He is not like Zeus, Thor, or Buddha—which is some powerful or enlightened figure within the cosmos. Rather, he alone has the peculiar nature that he could have continued existing just fine without having caused the cosmos to be. What are the requirements of this transcendent nature? For one thing, this nature cannot be bodily, because to have a body means to be wed to space, time, and the cosmos. God, the Creator of space and time, must be pure spirit.

The creed invites a reclamation of spirit, for it says that the Son “became incarnate.” He didn’t just become a man, but he took on flesh. This only makes sense if we realize that prior to the incarnation, he was fleshless spirit. How can we make such spirit intelligible?

I think we should look to St. Augustine who used some homey examples to make the point plain. He asks his listeners to think of a word, and then say the word. Now in speaking the word, the same word that existed in a purely immaterial way became physical. The thought that was immaterial is now physical, as well. Now, if I understand the word, at the sound of the word, I think of its meaning. But if I do not understand the word, all I can hear is the sound. So it is with Jesus. As eternal Word, he is pure spirit, but he became clothed with flesh so that he might be manifest. But to those who do not understand the language, they stop short at his flesh. To those who understand (those whom the Father gives understanding), he is rightly understood to be the Eternal Word.

We can see the spiritual meaning of physical words because we are spiritual beings created by a spiritual being.

Reclaiming the Incarnation

The bold novelty of the central Christian claim can lose its impact if we forget that God, by nature, is pure spirit. That God should take on flesh, then, does not mean that an immortal deity descended from Mount Olympus to interact with humans. It means, rather, that the immaterial creator of all things, himself no part of space and time, freely wed himself in his very person to a material being, entering space and time. He who is unchanging took on changing mortal flesh. There can be nothing more astounding than this fact, nothing more unprecedented, nothing more unforeseen. The author writes himself into his book, the playwright into his play, the creator into his creation.

By nature, God is invisible; but by means of the incarnation, God takes on a human face. This is a radical innovation on the part of God, a radical stooping down to meet the longing of human beings. For we are geared in our natures toward knowing visible things. We crave the visible, and recoil before things too difficult to imagine. Of course, God became incarnate principally to save us from sin, but the means he freely chooses suggest he is also interested in self-disclosure. God wants us to know him, and to know his love for us and, therefore, condescends to this radical self-emptying.

God now has a human face. To contemplate the face of Christ is to be mindful of the radical innovation of the incarnation. The invisible God has made himself visible. The iconoclasts wrongly retreated from the truth of the incarnation in rejecting icons of Christ, for this is precisely the central claim of Christianity: God who is spirit took on flesh.

On the twelfth centenary of the Second Council of Nicaea, Saint John Paul II issued a letter celebrating its defense of sacred images. He quoted Pope Hadrian I, who wrote:

Sacred images are honored by the faithful so that by means of a visible face, our spirit may be carried, in a spiritual attraction, towards the invisible majesty of the divinity, through the contemplation of the image where the flesh, that the Son of God deigned to take for our salvation, is represented. May we thus adore and praise him together, while glorifying, in spirit, this same Redeemer for, as it is written: “God is spirit,” and, that is why we spiritually adore his divinity.

Consider the gift of Jesus Christ from the perspective of making God visible. Now, place alongside an image of Christ, an image of the Father as an old man. The juxtaposition completely undermines and dilutes the radical truth of the incarnation. It suggests, rather, a basically pagan notion that the Son merely came down from Mount Olympus. But if we emphasize instead that the depiction of the Father is precisely the Son, then the incarnation comes to the fore in its fullness and boldness.

Wittgenstein famously said the body is the best picture of the soul. We can adopt this to our purposes and say: “The incarnate Son is the only picture of the invisible Father.” There are representations, such as the three angels who visited Abraham, or the pillar of fire that guided the Israelites through the desert, but no other portraits or pictures besides Jesus. We shouldn’t dilute the truth of the incarnation by depicting God in any other way.

Practical Suggestions

Consider the case of St. Augustine. The Manicheans had convinced him that Catholics interpreted the imago dei to mean that God had a body, too, a view he rightly found ridiculous. But it was only through the preaching of St. Ambrose that he came to realize the plain truth: God ain’t got no body! (Confessions VI.3.4) The corollary is worth emphasizing: if we are created in the image and likeness of God, but God does not have a body, then the imago dei points to our spiritual natures. If you worship a physical being, you will think of yourself as one. If you worship a God who is spirit, you just might discover that you, too, exist in a spiritual dimension. For the sake of our Faith, and our self-understanding, God’s spiritual nature is a truth well worth advertising. Here are three themes to correct the errors of today’s confused Augustines.

1. Reintroduce “spirit.” Once a year, remind the faithful that Christian art that depicts God as an old man is just an image, and that God is truly spirit. Michelangelo’s creation depiction rightly shows God’s personal involvement with each human soul, but we are not supposed to think of God as a man. If your church happens to have an image in which God the father is depicted as an old man, five times a year would not be too frequent to make the same reminder. Such an image will only be edifying if the faithful, when they see it, habitually transpose its literal meaning into its figurative meaning. They see an old man depicted, but are led to consider the providential, spiritual source of all things.

2. Commission new art. While no one has money to commission paintings and, even when the money is available, qualified artists are extremely rare, nonetheless I think the new evangelization calls for new images. To depict the Trinity, I think we should take seriously the Son’s claim that he alone is the image of the Father. We should depict Jesus as a man, but not God the Father. To depict the Trinity, then, I think we would do well to follow Scripture. There are several beautiful “Trinitarian moments” in the scripture. Consider the baptism of Jesus, where the clouds part, a voice thunders, and the spirit descends upon Jesus as a dove. Consider especially the transfiguration, in which the Father’s voice announces: “This is my beloved Son; listen to him.” A depiction of the scene could represent the Father by quoting his words. God is personal, he speaks, knows, and loves, but he is not a bodily being. To represent the Father through his words also recalls the act of creation which God accomplished without toil simply by speaking. The words of God constitute a good image of the Father. Now that our faithful are literate, there is no need to substitute for this image.

3. Get metaphysical. God is the creator and so he cannot be part of creation. Make this concrete by imagining what it would be for Walt Disney to have drawn himself into Snow White. To be the creator of her cartoon world, he would himself have to belong to a different dimension; he would have had to be a non-cartoon. When he entered into the cartoon world, he would have had to assume a cartoony nature. Similarly, God must be by nature outside creation as pure, immaterial spirit. He is the necessary being who continuously sustains us contingent beings in existence. The incarnation, then, is the radical act of spirit assuming flesh, creator becoming a creature.

The First Vatican Council eloquently stated this as follows:

As he is one unique and spiritual substance, entirely simply and unchangeable, we must proclaim him distinct from the world in existence and essence, blissful in himself and from himself, ineffably exalted above all things that exist or can be conceived besides him.

When we are up against people who insist that the physical explains the mythical, we must remind them that our religion belongs instead to the realm of the metaphysical, and as such, resists their reductive analyses. God is not something biological or physical. We have no choice today but to add a solid dose of metaphysics to the homilies and teaching we offer up for the edification of the faithful. Otherwise, with empty heads, they will continue to wander off into the darkness.

Do you mind taking this one step further? What is a good way to explain the following: “Since God is pure spirit, and Jesus is God, how do we reconcile the fact that He ascended into heaven with His human body, but as God, is pure spirit?” I’ve heard it explained that He ascended with His “glorified body”, but that doesn’t do much for school children and even most adults. Does that mean that the body He ascended with was pure spirit? If so, the next question always is, “Then what happened to His earthly body?”

Thank for some tips you might offer on how best to respond to this.

Perhaps the image of the Father as an old man is taken from the Ancient One from Daniel chapter 7.