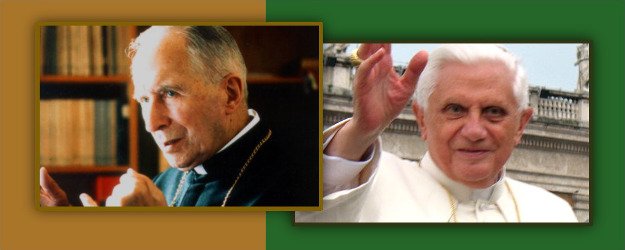

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and Pope Benedict XVI.

Question: I see and read all the “opinions” on whether the SSPX Mass and administering of the sacraments is legal and licit. Good people are at variance with each other on this issue. Please, could you straighten this out from your standpoint?

Answer: An excellent source on this subject, which treats it at greater length, is www.canonlawmadeeasy.com. Some history is necessary to understand this problem. The SSPX movement grew out of a protest movement largely centered on the late Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre over certain innovations, and theological interpretations of the teachings and practice of the Second Vatican Council. Among these was the reform of the Roman Rite which, though mandated by the Council, took such a strange turn that even Pope Benedict XVI called for a “reform of the reform.”

While rightly questioning some of the difficulties in the present liturgy, Archbishop Lefebvre and his followers established the Society of St. Pius X in 1970 without any ecclesiastical approval. This Society simply wished to preserve the traditional liturgy, something Pope Benedict recently approved for the whole Church, calling it the “extraordinary form” of the Roman Rite. The trouble is that, both then and now, they went far beyond this. Some denied the validity of what is now known as the “ordinary form,” and even went so far as to maintain that the See of Peter had been vacant since Vatican II. Some of the emphases on the teaching of the Second Vatican Council were also rejected. Still, since the Society’s attitude toward certain doctrinal teachings was unclear, they were not then considered heretics, nor are they now.

The institutional difficulty went further with a formal break when Archbishop Lefebvre consecrated four bishops without the approval of the pope in 1988. This was a schismatic act. A schism is not a rejection of doctrine in the intellect, but more a problem of the unity of charity in the will, which should reign in the heart of the Church. It is a non-collegial act, respecting the whole episcopacy and, especially, the union of the Society with the pope. As a result, the four bishops were excommunicated, though Pope Benedict later lifted this excommunication. The Society, however, despite repeated efforts on the part of the Holy See, has remained obdurate in not returning to canonical union, and continues to act on its own.

The ordinary Catholic may be presented with a dilemma. There may be a church of the SSPX in the neighborhood which provides a beautiful and exalted liturgy, while a church in union with Rome may present a secularized and banal liturgical experience. Pope Benedict reflected on this situation in 2009: “As long as the Society (of Saint Pius X) does not have a canonical status in the Church, its ministers do not exercise legitimate ministries in the Church. (…) In order to make this clear once again: until the doctrinal questions are clarified, the Society has no canonical status in the Church, and its ministers—even though they have been freed from ecclesiastical penalty—do not legitimately exercise any ministry in the Church” (Letter, March 10, 2009).

Regarding their sacraments, one must say that, with the exception of penance and marriage, which require special delegation, they are all valid, but since they are celebrated in disobedience, the ministers are sinning against the unity of the Church in performing them. As a result, it would be cooperation in this disobedience to attend them, unless there were no other alternatives available. Penance requires jurisdiction from the Church, and marriage must be according to the canonical form, unless there is a dispensation. Except in danger of death, penance could not be validly administered in SSPX churches. Since marriage requires jurisdiction, the same would be true of marriage.

____________

Question: What is the total loss when a mortal sin is committed?

Answer: First, it is important to realize what a mortal sin is, and how it differs from venial sin, as many have denied this distinction. Protestant churches, and the Jansenists, tended to treat all sins as the same. Since Vatican II, many Catholic moralists have embraced the erroneous doctrine that there is a difference between grave sin, and mortal sin. Grave sin would be a violation of the commandments in a serious matter. Mortal sin would involve a fundamental personal option against God himself. Venial sin would be a refusal to grow. This last could stand, if it means anything at all, but the former distinctions are wrong. The Church has clarified that, regardless of the person’s intention directly respecting God, if a person has an intention to do a deed which is gravely contrary to the commandments, this is a mortal sin. The Catechism states: “Sins are rightly evaluated according to their gravity. The distinction between mortal and venial sin, already evident in Scripture, became part of the tradition of the Church. It is corroborated by human experience. Mortal sin destroys charity in the heart of man by a grave violation of God’s law; it turns man away from God, who is his ultimate end, and his beatitude, by preferring an inferior good to God. Venial sin allows charity to subsist, even though it offends and wounds it” (§1854, 1855).

In addition, there are three conditions required for a sin to be mortal. First, it must be a grave matter. This means that the person must will something which is so disordered in love, that it is a serious rejection of the truth with which God orders the world. Such a rejection of the order entails a rejection of the Orderer, even if the person does not consciously intend to reject God at that time. In addition, since nothing is willed unless it is first foreknown, the person must know that the action involves a grave matter. This does not mean that he must have the knowledge of a theologian. It suffices only for him to know that the action is gravely contrary to the moral law. In forming his conscience, the person has an obligation to do all in his power to discover this. If, however, there were no way he could know this, for example, by ignorance of a circumstance, then he is not guilty of a mortal sin.

This does not mean that his act is good. The last condition is that the person must have full use of his free will in doing this deed. Factors like external pressure, fear, or psychological illness can mean that, even though he may consciously do a deed, he may not have full use of his will in doing it. For example, adolescents, or children, could do an action considered gravely sinful, but, in many cases, do not have the maturity required for complete responsibility.

If all three of these conditions are present, then the will enters into a condition in which a good is desired which is disordered in relation to the world God has made, and this disorder passes into the interior life of the person himself. He has set himself at enmity with the Creator. Heaven is a reward after death for a person who is in love with God. This love is proven in keeping the commandments of the one who says he loves God. Grace is the means by which we arrive at this end, for it is nothing else but the fruit of divine love in the soul. “Whoever says, ‘I have come to know him,’ but does not obey his commandments, is a liar, and, in such a person, the truth does not exist” (1 John 2:4). In addition to the grace necessary to arrive at heaven given in baptism, each person receives the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity, and the infused moral virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude. These allow a person to live a life of grace so as to arrive at heaven.

Some modern theologians have maintained that the punishment for someone who dies unrepentant for mortal sin, will cease to exist, and will pass into nothing. This is simply wrong, and does not correspond to the teaching of the Church. A mortal sin is called “mortal,” not because the soul is killed, in the sense that it ceases to exist, but since God and grace are the life of the soul. An immortal soul which loses grace is lifeless, and a person who dies unrepentant in this condition enters eternity with his soul, and eventually his body, intact but unfulfilled. This lack of fulfillment will exist forever, for freedom and nature have disagreed. Without being able to see God, such a person remains completely frustrated in the deepest recesses of what he is as a human being. In other words, he is in hell. Then, the short answer to this question is that by mortal sin, a person loses grace, the infused moral virtues, and faith, hope, and charity as virtues. Faith and hope remain, but are dead. A person who dies in such a condition goes to hell.

1. Pope Francis, in his Bollettino of 01.09.2015, granted all priests of the Society of St. Pius X the faculty of administering the Sacrament of Penance during the Jubilee Year of Mercy. Yet, now, more than four months later you do not happen to mention this development, which surely, at least, must be of some Ecclesiastical and forensic significance.

The question is what significance will it have for the SSPX