When EWTN aired Raymond Arroyo’s first “World Over” television interview with Dean Koontz on October 18, 2012, many viewers were surprised to learn that the author of over a dozen #1 New York Times bestsellers is a practicing Catholic. The longtime writer, whose name is often mentioned alongside such horror and suspense greats as Stephen King and John Saul, boasts a vast oeuvre—more than seventy books—and with his wife, has run a charitable foundation for more than two decades focused on the severely disabled and children who are ill. He even regularly dines with some nearby Norbertines.

In Arroyo’s estimation, Koontz’s “Catholic faith informs all of his work,” and Koontz’s answers in that interview, and in the two follow-up sessions that were filmed over the next two years, affirm that evaluation. Catholic teaching may not be explicitly present in his works, but Koontz’s recurring themes rest on that bedrock faith: the genuine power of supernatural evil in the world; the greater power of supernatural good that fights it off, revealing evil to be nothing more than a corruption of the good; and the strength of sacrificial love in binding together communities that unite against the ever-threatening darkness.

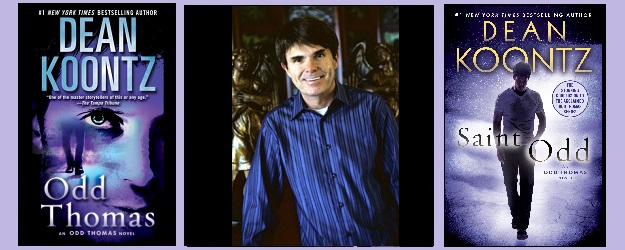

Nowhere better do we see this divine drama playing out in Koontz’s fictional worlds than in the Odd Thomas (2003) series, a prominent topic in Arroyo’s first interview. Originally planned as a seven-book series—with each volume corresponding to a capital virtue—Koontz compiled some digital stories into a bonus collection (the appropriately titled Odd Interlude) to bring the total to eight. The series finale, Saint Odd, came out on January 13, 2015. Readers were eager to see how Koontz would wrap up some particularly vexing literary questions—and some spiritual ones, as well. Now seems like a very acceptable time, then, to read Koontz from a fresh perspective—dare I say an “Oddly Catholic” one.

For those not acquainted with the series, a brief, mostly spoiler-free introduction will do. Odd Thomas—our protagonist, whose first name may be a misprint of “Todd” from his birth certificate—introduces himself in the eponymous first book as a twenty-year-old fry cook in the small desert town of Pico Mundo. We learn rather quickly that Odd can see the spirits of the dead who have not, as he says, crossed over—those who are too scared, sad, or angry to do so, and some of whom want to help with remaining matters of justice, even though they cannot speak. With self-deprecating, witty humor, and a down-home, guy-next-door attitude, Odd quickly wins the reader’s sympathy. Thus, when the spirit of a very young victim of sexual assault and murder approaches him in the first chapter of the book, and is able to indicate her killer, we are already on Odd’s side, hoping for recompense. With the speed and clarity of action for which Koontz has become famous, Odd, by the end of the first chapter, has confronted the perpetrator—with dialogue that hits just the right notes of pity and disgust—and vaults into hot pursuit of the terrified, fleeing criminal.

Conscientious Christian readers might at this point pause, wondering if a novel about a so-called “medium” is right reading (while visions of the Index librorum prohibitorum dance in their heads). After all, as Peter Kreeft has reminded us, such an occult activity as being a “medium” is encouraged by “the same evil spirits who inspire human sacrifice.” 1 As becomes clear in the book—and as Odd will affirm throughout the series—he has never asked for what he calls his gift, and in down times, he is tempted to consider it a curse. After all, it brings him into contact with villains: like a violent group of well-hidden demon worshippers ready to wreak havoc on an unsuspecting town; an accomplished practitioner of Voodoo bent on harnessing Odd’s gift for her own nefarious purposes; and biological terrorists ready to trade millions of lives for their pick of what Fr. Barron, in his Catholicism series, refers to as Aquinas’ four substitutes for God: honor, pleasure, power, and wealth.

Even in the face of such unsightly evil, Odd describes his holy longing for souls in terms evocative of the Sacred Heart: “Sometimes it seems that to exit this world, {the spirits that I see} must go through my heart, leaving it scarred and sore.”2 Odd’s melancholy, moreover, never lasts more than a moment: “To keep the sorrow from overwhelming me, I remain focused on the beauty of this world, which is everywhere to be seen in rich variety.”3 Thus infused, Odd always returns to that rather insistent desire of his to use his talents for others. Countering his girlfriend, Stormy, and her half-joking accusation of his “messiah complex,” Odd responds: “‘It’s a gift.’ Tapping my head, I said, ‘I’ve still got the box it came in.” 4 “Deus providebit” (“God will provide”), we might echo in the background, in hearing Odd’s grateful affirmation of how many near-death scrapes he’s come through alive—the gratitude that compels one to give everything in love to others. Or, as Odd will put it in the third book of the series, he trusts his gift as “a miraculous thing, which in itself suggests a supernatural order.” 5 That supernal kingdom, and its overflowing mirth, Odd acknowledges directly in a telling moment in the second book. Commenting that his gifts don’t always “work,” Odd knows, nonetheless, that it’s not God’s fault: “The unreliability of this gift is not proof that God is either cruel or indifferent, though it might be one proof among many that he has a sense of humor.” 6

The bestowal of extraordinary spiritual gifts on those of extraordinary virtue is a hallmark of the saints. One thinks of Padre Pio’s initially reluctant acceptance of the stigmata, for instance, or of John Bosco’s many prophecies. If Odd has received an extraordinary gift meant to be given away in self-sacrificing love for others, one would expect Koontz to follow suit by characterizing Odd appropriately. The question, then, is how Koontz can relate this Catholic vision to his vast audience without writing in the so-called Catholic “parable novel” genre, which has little currency in the mass market, and is generally either derided as propaganda, or dismissed as devotional. It goes without saying, of course, that Koontz avoids the axis of popular religious fiction, which pits Zondervan-style piety on one end, against the seemingly contradictory supernatural secular, and so-called “magical realism,” on the other.

Like many great Catholic authors before him, Koontz knows that writers who are believers get it wrong when they try to represent the divine in their works as a departed God, not substantially present among us at all times. One thinks of Flannery O’Connor’s famous line about the Eucharist: “Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it.” 7 Koontz instead embraces the “hidden in plain sight” view of literature—an “Adoro Te Devote” (“I devoutly adore you”) kind of writing that delivers the substance of Catholic teaching under the species of ordinary literary devices. Koontz writes Odd as a character who, in light of the Catholic tradition, responds to the extraordinary gift of seeing souls in Purgatory by taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—the evangelical counsels that keep Odd’s life simple, and his heart ready to serve, as he often reminds us with an amusing aside. Odd doesn’t call them that, in so many words, but Koontz’s depiction is something more than implicit, even as it’s just short of explicit—hidden in plain view.

Consider, for instance, how Odd shows us where he lives: a small, rented apartment above a garage, where he keeps his entire wardrobe—a T-shirt or two, a couple pairs of jeans, and maybe more than one pair of sneakers—near the cinder-block furniture. Odd’s voluntary poverty precludes owning a car, yet he has sustained strong friendships throughout his community. So when he needs a friend, he is usually rewarded by the good will of others. Throughout the series, Koontz ties the simplicity of the evangelical counsels to God’s Providence. So by putting himself at the service of others through the obedience to his gift, Odd receives what he needs when he needs it—a kind of total abandonment that makes sense when, late in the first book, we meet Odd’s tragically dysfunctional parents (I will not spoil those scenes).

Not that Odd lives these vows perfectly; we’d be in the “parable novel” genre if that were the case. More convincingly—and probably more effectively from an evangelical or catechetical point of view—Koontz gives us in the first book several scenes in which Odd’s virtue is tested, and Odd doesn’t always win. He has a conversation with Stormy, for instance, in which he pointedly asks her why she’s afraid of intercourse, which, if they engaged in it, would be Odd’s first experience thereof. Through their dialogue we understand that he, in fact, knows the reason—that the couple has decided to wait, partly due to Stormy’s childhood sexual trauma. Odd knows why he made the cruel comment: Stormy had been pressing him to come to terms with his own fear of guns. To quote a villain in the recent T. M. Doran novel, Terrapin, “I suffer; you suffer. That’s a universe that makes sense to me.” 8 To put it another way, Odd averts his gaze from redemptive suffering in this moment—he is not quite ready to face the open wound of his resistance to using guns—and, thus, goes for an easy target in his beloved: “I can be stupid. As soon as I spoke, I regretted my words … the truth didn’t make me feel any better about what I’d done.” 9

Odd and Stormy make amends. Later in the novel, Stormy does offer what Odd was seeking, but he declines, as he will for the rest of the series. Koontz doesn’t offer us a polished chastity designed for spiritual showroom floors; after all, the trifecta for gauging culpability—intent, object, and circumstance—still applies. What he does give us, in Odd especially, is a young man who lives his vow of chastity out of dedication, and for the good of another—agape struggling with the purification of eros, as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI poignantly remarked concerning the journey of love often forgotten in the modern world.10 As Odd notices late in the series, while looking into a particularly pure woman’s eyes, “I am reminded that fire not only consumes; it also purifies. And another word for purification is redemption.” 11

While I will not reveal the big secrets of the end of the first book, I will say that Odd—like many spiritual masters before him, and the Master himself—chooses to go out into the desert. He leaves not in order to wander, but to allow his gifts to bring him where he might be needed most, often in isolated places. The solitude helps. Odd’s prophetic dreams often require time and effort to interpret, and his gift of “psychic magnetism,” a kind of spiritual GPS, just as often summons “the bad guys” to him, as it does him to them. Thus, the middle six books each occur in different locations, with the third volume, Brother Odd, standing out for its setting in a Catholic monastery.

As many a Koontz fan has observed, the middle six books unfortunately do not quite hit the winning strides of the first book (or the last, as early reports have indicated). Brother Odd, for instance, sets up what could be an intriguing plot regarding the relationship of faith and science. There are moving scenes involving severely sick and disabled children that do homage to the author’s charitable activities. But even though the book maintains an often light approach via Odd’s witty banter with other characters, Koontz often writes with too heavy a hand. In response to Odd’s question about what he wants to know, a particularly science-invested monk answers, “Everything,”12 and only readers unfamiliar with the literary legacy of Faust would not wonder if they had already pegged an antagonist. Later on, Odd remarks that a high-ranking monk “had embraced the false idea that God can be known through science,” 13 sending readers, familiar with the works of Stephen Barr and Robert Spitzer, running to their bookshelves for consolation. Indeed, this line seems at odds with Koontz’s own confession to Arroyo that it was science that brought him back to the faith after his disillusionment with what he saw as a post-Vatican II dilution of the faith. The Church that had supported ostensible contraries, to use G. K. Chesterton’s image, “side by side like two strong colors, red and white, like the red and white upon the shield of St. George” was, in its watering down of doctrine, beginning to lose its “healthy hatred of pink.”14

To be charitable—and to be fair to the scene’s context without ruining the surprise—Koontz means to cast aspersion on those who have done grave damage to others, especially the vulnerable, under the meretricious view that God can be known only through science. Granted that this is one word more than what Odd says, but given that Koontz dedicated a different novel (published just previously to the Odd Thomas series, One Door Away from Heaven) to fighting what he calls the evil of utilitarian bioethics, 15 we can avoid literalism and interpret charitably. Koontz means that the character who substitutes science for faith, finds himself one door away from Hell and, indeed, begins opening this world to the bent denizens of the outer planes.

This approach of charitable interpretation becomes increasingly important as the series resolves one of its most irksome puzzles: the role of a fortune-telling machine in Odd’s life, and its relation to a seemingly divine promise.

Near the first or last page of almost every book in the series is an image of a card dispensed from a supposedly “prophetic” carnival amusement. Written in small caps, art deco lettering, the card reads: “You are destined to be together forever.” Odd and Stormy received this promise from “Gypsy Mummy,” a “gaudy contrivance,” 16 as Odd calls it. Four years prior to the events of Odd Thomas, he and Stormy had visited the county fair where they discovered the machine. In one of the book’s funnier moments, Odd describes how Gypsy Mummy dispenses eight consecutive prognostications of marital gloom and doom to a couple standing in front of them in the line. That couple’s ensuing argument has us tipping our hats to Koontz, who knows that enduring love had better be able to parry such light-hearted attacks. The irony culminates in the fact that the next card, with its promise of eternal bliss, goes to Stormy and Odd.

Looking at the machine, Odd tells the reader that “most likely this was not the art of Death working in the medium of flesh, as claimed, but instead the product of an artist who had been clever with plaster, paper, and latex.” 17 Attuned readers might have experienced by this point visceral flashbacks to the pivotal scene of the false revelation of the “shrunken man” 18 in Flannery O’Connor’s novel, Wiseblood. In the novel, O’Connor’s character, the overly eager Enoch, invests a vapid imitation of mystery, and Haze utterly dismisses it with a tinge of self-absorbed nihilism.

But Odd is no Enoch nor Haze. In that winning sarcasm of his, Odd relates that Gypsy Mummy is a contrivance; he firmly denies its status as a “medium,” especially of a capitalized death—an area in which Odd himself has extraordinary expertise. Knowing Koontz, we might even see here a veiled reference via negativa to the Incarnation, not a bad definition of which is the art of Life working in the medium of flesh. Odd does leave open the possibility that even through such a machination could a lasting promise be delivered. He refers back to the card several times in the first book with the faith of a Flannery: “The promise of Gypsy Mummy would be fulfilled. Nothing else mattered.” 19 We learn that Stormy keeps the promise framed above her bed—traditionally where many Catholics place a crucifix—and later events in the book compel Odd to carry the card in his wallet—traditionally where those who haven’t taken a vow of chastity carry something else. And while a Catholic church plays only a minor role in the first book—Koontz names it “St. Bartholomew’s,” an appropriately grisly choice in a suspense novel given the manner of that martyr’s death—this choice speaks more to the “hidden in plain sight” vision we spoke of earlier. A scene of Odd opening the Bible and believing in God’s promises? Left Behind territory or worse, “parable tale.” Odd acknowledging that God can deliver his promises even through what someone recognizes as a false, poorly executed paste-up oracle? Almost Gerard Manley Hopkins territory and certainly Ignatian. Indeed, Ross Labrie terms this approach one of the Catholic literary imagination’s signs of an expanding scope, which he sees in those writers who are “grounded in the belief that there is nothing on earth that is inaccessible to God’s mercy.” 20 That said, Odd often makes clear that God’s mercy, in some cases, means—at the least—renovation, as when in the fourth book, Odd finds in a modern church “above the altar, the abstract sculpture of Big Bird or the Lord, or whatever.” 21

As I’ve mentioned, Odd only fleetingly recounts the Gypsy Mummy story in Odd Thomas, and while he briefly introduces it to would-be new readers in subsequent books, Koontz never fully satisfies the reader as to why Odd believes in it. To generate some hype for the release of Saint Odd, Koontz released an e-short story sharing the same name as the fateful words on the Gypsy Mummy card. I haven’t read this, mostly because Koontz’s highly attentive fan-base classified it as a mere side adventure with no real meat—a teaser, at best, for Saint Odd. The series’ finale does, however, contain a highly significant scene that finally answers those nagging questions about Odd’s belief in the promise of the card.

I will ruin almost nothing by saying that the scene happens at a carnival, where once again Odd finds Gypsy Mummy amidst a gaudy display of exactly thirty-three machines, a number Koontz repeats in case readers miss it the first time (which is, as any seminarian will be proud to tell you, the number of buttons on a Roman cassock). Amplifying his judgment of the appearance of the thing from the first book—“the figure had most likely been sculpted by a low-rent artist who worked best when inebriated” 22—Odd follows the printed instructions to speak his request aloud. “‘How long do I have to wait,’ I murmured, ‘before your promise to me comes true?’” 23 He gets a blank card. And, each of the three times he repeats the question, and puts in his four bits, he receives the same: a blank card. Odd waits surreptitiously to see how the machine dispenses to other people, and when they don’t receive blanks, he gets pensive.

Odd first acknowledges that chance would be a rational response, but then argues that the extraordinary tends to play a rather ordinary role in his life. Contemplating that, he tells us that “for six years, I had believed in the message on the card in my wallet … sometimes it alone had sustained me. I could no more stop believing in Gypsy Mummy than I could stop believing in my own existence.” 24 Odd does not subscribe to the notion that Gypsy Mummy is a mere collection of atoms; he avoids a materialistic view that would preclude some kind of spiritual intervention. More crucially, Odd has gone to some pains to tell us that he knows the machine is not a spiritualist means of divination, nor a magical effort “to tame occult powers,” 25 as the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it. In fact, in order to put Odd’s comments in Saint Odd in context, we ought to step back for a moment to book seven, Deeply Odd.

In many ways the most disturbing book of the series, Deeply Odd has our hero chasing down a truck driver with a rather strange cargo to a house of demon worship. Odd is aided by a group of what might best be called the underground Catholic militia, who are armed with ordnance of which even Kyle Myers of FPSRussia fame would approve. In one of the climactic scenes, Odd attempts to rescue a number of children who are due to be sacrificed, as if to Moloch. In an endgame, which ranks among the goriest in the whole series, Koontz shows the predictably horrible effects of a villain’s attempts to domesticate a demon.26 In the aftermath of that devil worship gone disastrously awry (as it always will, Koontz makes abundantly clear), Odd shows his Gypsy Mummy card to a benevolent spirit, saying, “I trust it totally. I’m sure it’s the truest thing I’ve ever known.” 27 The spirit—who happens to be a Jesuit-trained celebrity I won’t name here—responds with a knowing smile to Odd’s insistent response to tell him what he thinks of the card: “‘You’re not ready to leave this world yet, Mr. Thomas.’” 28 Having Odd’s best interests in mind, the spirit not only tacitly approves of Odd’s trust, but pushes further in linking that promise to the next world—one the spirit knows well.

With this context in mind, Odd’s comments about belief in the card in Saint Odd seem laudable, even noble: he is able to see God’s promise working through an extraordinary channel, and he honors the ordinary means through which it was delivered, even as he judges that ordinary means for what it is. His ultimate response to the blank cards delivered this time around only reinforces this interpretation, for Odd once again springs into action, hoping against hope that the blankness of the cards means he has no time to lose in foiling the debauched masterminds again threatening his hometown. Though Jean Corbon would undoubtedly say it more beautifully, we can summarize Odd’s belief in the promise of the predestination of self-forgetting love—his drawing from “the wellspring of worship 29 at an unlikely source, as it were—as this: good prayer leads to good action. As Koontz himself has said, “writing is meditation, sometimes even prayer.” 30

Though I may seem to have spent a considerable amount of time elucidating this particular point, I have done so because Koontz, to his great credit, consistently and invariably uses this material/spiritual technique when invoking the extraordinary. Very early in the first book, for instance, Odd has told us that these, his “memoirs,” (he hesitates out of humility to call them even that) would not be published until after his death. Thus, we know from the beginning that Koontz will have a thorny narrative problem to solve at some point. How do we hear of the adventure resulting in Odd’s death, presumably in his own words, without his descending into some version of Moby Dick’s Book of Job reference: “…and I only am escaped alone to tell thee”? 31 Worse, would he render intentionally what a European publisher of Moby Dick did unintentionally: leave out an explanatory epilogue and thus send readers into a conundrum about how the hero “could narrate the story when he had perished?” 32

I am happy to report that Koontz does, indeed, provide an explanation, though many readers will, at first blush, find it hokey. Keeping in mind, however, what we have just discussed, the savvy reader will understand that Koontz has merely been consistent in his use of the extraordinary. I will provide the following hint. Those who are familiar with the ministry of genuine exorcists, like Fr. Jose Antonio Fortea, know that spirits can, in very rare cases, possess materials. Popular ecumenical writer, Anthony DeStefano, tells such a story about furniture in his book on prayer. 33 Koontz quite logically asks: if God allows evil spirits to do such things, why not, in similarly rare circumstances, good ones? I will leave it at that, with a caveat from Kreeft regarding “supernatural interventions: You might experience it, but you shouldn’t expect it.” 34

Just so, one mustn’t expect me to do much justice to a roughly 3,400-page series in a short article—but I have tried to advance Koontz’s Catholic approach which I believe to be an increasingly important one, given the popularity of other kinds of religious fiction predominant in the market. In her examination of many of Koontz’s novels published before the year 2000, Linda Holland-Toll shows that through a deft straddling of both the horror and adventure-suspense genres, Koontz manages to shake us up in order to re-establish, or even strengthen, our deeper comforts: “his novels consistently restore and affirm the basic values that he defines as important … the vicarious experiences may be safely enjoyed.”35 Yes, Koontz knows how to toe those fine lines, and at the same time, for the believer, he points us to the good and the true: literature that is “directed toward expressing, in some way, the infinite beauty of God.”36 While Koontz is, in one sense, addressing the complacent and lukewarm through an absolute avowal of the threat of evil, he is also not engaging in what Paul Elie sees as the contemporary literary response to O’Connor’s injunction to “‘make belief believable’… writing fiction in which belief acts obscurely and inconclusively.” 37 As I mentioned at the beginning of this piece, Koontz writes somewhere in-between these positions: not glaringly explicit, nor obscurely post-secular, but hidden in full view. To take Jacques Maritain’s thoughts on poetry, and apply them to fiction, it would be mortally dreadful to hope that Koontz’s works could “produce the super-substantial nourishment of man,” 38 and Koontz has no delusions thereof. But just as something good begs the question of something greater, perhaps the greatest accomplishment of the Odd Thomas series can be found in its finale as it sends up its hero’s sacrifices and sighs as a response to this valley of tears. Therein lies one of the series’ best-kept secrets, which I will allow readers to experience for themselves in the extraordinary dealings of Dean Koontz’s “Odd Catholicism.”

- Peter Kreeft, Angels (and Demons) (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 115. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Forever Odd (New York: Bantam, 2005), 151. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Odd Apocalypse (New York: Bantam, 2012), 140. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Odd Thomas (New York: Bantam, 2003), 71. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Brother Odd (New York: Bantam, 2006), 59. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Forever Odd, 19. ↩

- Quoted in George Weigel, Letters to a Young Catholic (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 16. ↩

- T. M. Doran, Terrapin (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2012), 356. ↩

- Koontz, Odd Thomas, 173-4. ↩

- Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, §7. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Odd Interlude (New York: Bantam, 2012), 16. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Brother Odd, 61. ↩

- Koontz, Brother Odd, 417. ↩

- G. K. Chesterton, The Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton: Volume 1 (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1986), 301-2. ↩

- Tim Drake, “St. Odd?” National Catholic Register (March 6, 2007). ↩

- Koontz, Odd Thomas, 231. ↩

- Koontz, Odd Thomas, 232. ↩

- Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1949, 1962), 94. ↩

- Koontz, Odd Thomas, 430. ↩

- Ross Labrie, The Catholic Imagination in American Literature (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997), 275. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Odd Hours (New York: Bantam, 2008), 304. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Saint Odd (New York: Bantam, 2015), 117. ↩

- Koontz, Saint Odd, 118. ↩

- Koontz, Saint Odd, 119-120. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, §2117. ↩

- Dean Koontz, Deeply Odd (New York: Bantam, 2013), 314 ff. ↩

- Koontz, Deeply Odd, 321. ↩

- Koontz, Deeply Odd, 322. ↩

- Jean Corbon, The Wellspring of Worship, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2005), 21-22. ↩

- Tim Drake, “Chatting with Koontz about Faith,” National Catholic Register (March 6, 2007). ↩

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick; or, The Whale, Charles Feidelson, editor (New York: Macmillan, 1964), 723. ↩

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815 – 1848 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 634. ↩

- Anthony DeStefano, Ten Prayers God Always Says Yes To: Divine Answers to Life’s Most Difficult Problems (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 111 ff. ↩

- Kreeft, Angels (and Demons), 102. ↩

- Linda J. Holland-Toll, “From Disturbance to Comfort Zone,” The Journal of Popular Culture 37:4 (2004), 663, 666. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, §2513. ↩

- Paul Elie, “Has Fiction Lost Its Faith?” New York Times Sunday Book Review (December 23, 2012), BR1. ↩

- Quoted in David Lyle Jeffrey and Gregory Maillet, Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2011), 327. ↩

Interesting article! Thanks for writing it! God bless Mr. Koontzs!

After watching Mr. Koontz on The World Over, I bought, a very random selection, his book, “The Hideaway.” In it, the devil tells a young man he hasn’t done enough evil on earth, and sends him back to earth to do more. Upon returning, he randomly kills. When the subject is a woman, he rapes her, tortures her, and then kills her. If you can consider this to have a “Catholic” flavor to it, you have a very “odd” sense of Catholicism.

What you describe, Ed, sounds very little like Koontz’s “Hideaway,” in which an innocent man is supernaturally linked to the mind of a psychopathic killer, and through this link is actually able to engage in some spiritual warfare that leads to an exorcism.

Koontz wrote a new Afterword for the book in 2005, revealing that the hate mail he got was predominantly from atheists who were angry that Koontz “assumed the existence of God and heaven.”

There was a very bad movie version made of this book; so poor was the film that Koontz apparently wanted his name removed from it entirely.

Thats is really good after watching an interview of Koontz on “World Over,” I was really impressed with his authentic Catholic ideal in his work. Thanks be to God he is another great example of living the faith whatever state in life in a secular world.