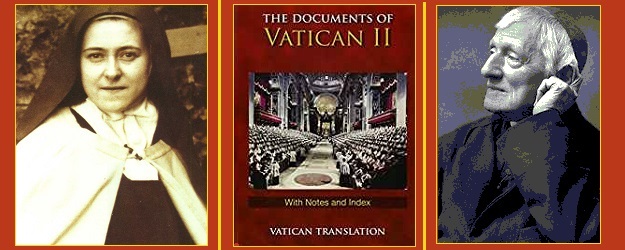

It is common these days to read of certain figures whose contribution to the Church in some way prefigured the reforms of Vatican II—e.g., de Lubac, Congar—but among them also are the figures of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the Little Flower, and Cardinal John Henry Newman. (They will be referred to as “Thérèse” and “Newman” in this article.) Their contributions are the subject of this essay, not in terms of exact and specific contributions to the fully developed doctrine of current Church teaching on the laity, but in terms of the development of spiritual aspirations of lay people—namely that it is not necessary to be a priest or a professed religious to seek the higher altitudes of Jesus’ holy mountain. Both insisted that the highest degrees of holiness, and lively participation in spiritual life, are not restricted to cloistered nuns, or ascetic monks, but are available to lay people, as well. Both figures then, the cloistered nun and the Oxford Scholar, wrote and inspired lay spirituality that was prophetically aimed at the full enunciation of the teaching by the Catholic Church in the documents of the Second Vatican Council and the Catholic Catechism.1

Even though both are 19th Century religious figures, they are strikingly different:

- Newman is English, Thérèse is French;

- Newman is reserved and austere, Thérèse is outgoing and charming;

- Newman is an Oxford university scholar, Thérèse has the equivalent of a high school education;

- Newman is a mover and shaker in both the Anglican and the Catholic churches; Thérèse is unknown outside a close circle of family and friends;

- Newman leaving behind monographs, volumes of sermons and prayers, and thousands of letters; Thérèse leaves only a few letters, and her spiritual autobiography which is very short;

- Newman’s argument on behalf of Church reform was publicly rejected by the Anglican bishops; Thérèse agonized over her father’s sarcastic comment about Christmas gifts;

- Newman lived to reach 90 years: Thérèse died at age 24.

Yet, the commonalities are more important. Both led saintly lives:

- Thérèse was formally canonized not long after her early death;

- Newman was recently beatified; both left behind influential autobiographies;

- Newman’s autobiography used the Latin title Apologia Pro Vita Sua (although the text is in English) indicating his scholarly approach towards his personal religious development;

- Thérèse’s autobiography was subtitled “The Story of a Soul” indicating her concern with souls, others’ as well as her own, for she wished above all to bring souls to Christ.

Their Life Stories

A brief account of the life stories of these two remarkable figures will be useful. Newman’s life is remarkable not only for its length of 90 years, but for the number of incidents with large consequences that filled his life. This included being the spokesman for the “Oxford Movement” within the Church of England, which was the controversial attempt to bring in ancient liturgical forms, and the study of the Church Fathers. For this he was accused of being a secret agent of the pope. His subsequent conversion to the Catholic Church was seen to validate the suspicion of his fiercest Protestant critics. There were the subsequent attempts by Catholic Church authorities to find a large project for him which included starting a university in Ireland, a new translation of the Bible, and starting a journal for lay Catholics—all of which came to naught. His accomplishments included establishment of an Oratorio for priests on the model of St. Philip Neri; the subsequent decades spent as a parish pastor in the working class city of Birmingham with a large population of Catholic working class families; and then, 20 years after the fact, Newman responded to the claim of a Protestant author who accused Newman of outright duplicity, and that Catholic priests taught “lying on system” in his famous Newman’s Apologia. Added to all of this activity throughout his life, Newman, the scholar, wrote books on Arianism, on the development of doctrine, on justification, and his final effort being on the epistemology of religious belief, or as Newman entitled it in his elevated manner: “grammar of assent.”

The main point of Newman’s life may be lost, however, if we ignore his early sermons as a member of the Anglican Church, which he was for the first half of his life (up until the age of 44). These “Plain and Parochial Sermons” were given over a period of 15 years, starting from 1828, when Newman was the main preacher, and later Vicar, of St. Mary Church, which was Oxford’s “official” church. The main emphases of Newman’s religious teaching were first enunciated in these sermons, on love of God, and on the true nature of man in his inner being as he approached the summit of human concerns: man’s relationship to God. The impediments to total engagement are many, according to Newman, and usually unsuspected by religious people. It was Newman’s job to expose the impediments for his congregation in order to enable them to understand the importance of religious belief, beyond the formal association with the Church of England. His audience for these sermons—which are famous enough to have been reprinted several times since he first gave them (now published in one volume by Ignatius Press)—was a combination of students, professors, staff, and workers at the University, plus local residents of the Themes valley. It was to this mixed congregation of Anglican believers that Newman delivered his weekly sermons for which he became famous. In them, Newman laid out, over time, and in many different ways, the program for lay spirituality, and the attainment of holiness.

One such sermon is entitled, “Love, the One Thing Needful,” which, while written in Newman’s elevated style, is not an encomium on Christian charity, but comes down to cases understandable by any Christian believer.2 In this sermon, Newman addresses the Christian believer, not the skeptic. The sermon is well organized—an outline may be easily made of it. For example, he gives tokens that the believer does not love enough as a main heading, followed by three examples, etc. Its aim, however, is not to convince by means of formal argument, but to encourage the believer to greater devotion, so that the performance of religious duties is motivated above all by the believer’s love of God. “Love, and love only, is the fulfilling of the Law, and they only are in God’s favor on whom the righteousness of the Law is fulfilled.” [p. 34]. It is a hard doctrine that Newman proposes, for “… the comforts of life are the main cause of [lack of devotion], and … till we learn to dispense with them in good measure, we shall not overcome [spiritual lassitude]” [p. 42]. Newman assumed, in other words, that his hearers want to be good Christians, but do not know how. He describes calmly their state of performing required duties unaccompanied by a sense of the love of God, but he does so in devastating detail. He concludes by encouraging constant recollection of the Crucifixion: “Christ showed His love in deed, not in word, and you will be touched by the thought of His cross far more by bearing it after Him, than by glowing accounts of it.” [p. 43]

The highest mountains do not often stand alone on a flat plain from which they arise in dramatic splendor; rather the highest peaks are usually a part of a mountain range made up of many high mountains. So it is in Thérèse’s case, for her entire family consisted of saintly people. Her four sisters all became nuns, three of them in the same Carmelite convent as Thérèse. Her parents, Zelie and Louis, were a particularly devout married couple; both of whom have recently been canonized in order to join their youngest daughter, Thérèse, in the Church’s calendar of saints. Although this background of a saintly family gives a context, the particular sanctity of St. Thérèse remains something of a mystery, since unlike Newman, or Thérèse’s namesake, St. Teresa of Avila, she accomplished nothing which was notable in the public sphere.

Thérèse’s autobiography is quite short, and frankly lacking the emotional punch, and intellectual penetration, of the best-known, spiritual autobiographies, such as St. Augustine’s Confessions. Nonetheless, the reader may be overwhelmed by Thérèse’s recounting of her intensely emotional responses to the events of her early life, even as she criticizes herself for her over-emotional responses. Here, we enter on a sensitive topic, for the girlishness of Thérèse’s account, with its description of ribbons, the birds, and small animals she kept as pets, her devotion to her father—her “King,” the seeming lack of any dramatic, or consequential events in her short life (except the death of her mother, Zelie), and the dramatizations of the day-to-day events of her middle class family life, can be off-putting for some readers (including Thomas Merton). So, the reader must get beyond such difficulties by noting that her reaction to these small events all pointed to advancement in the spiritual life. She describes her reaction to her sister Marie’s leaving the family for the convent. “As I was the youngest, I wasn’t used to looking after myself. Celine tidied our bedroom, and I never did a stroke of housework. But after Marie entered Carmel, I sometimes used to make our beds—to please God. … As I did this for no other reason than to please God, I shouldn’t have expected any thanks for it. Yet, if Celine didn’t look surprised or pleased, I cried with disappointment.” (Thérèse was about eleven years old.)

What stands out, after all, is Thérèse’s complete devotion to God in the form of love of Jesus, her humility as she grows up in a seemingly conventional family, and takes her place in convent life, for at every small point in her recitation, she is in view of her desire to attain sainthood, and to pass along to others what she has learned in her short, but intense, journey to God. The result of Thérèse’s journey is her “little way,” the way simple souls who live a common life as unexciting and undramatic as her own, may yet aspire to holiness. The little way of doing things for love is openly accessible to any soul who attempts it, which is its great virtue. It may seem nothing more than a charming conceit, a spiritual balm for the lay person who knows she is not a great saint by the common nature of her daily life, and lack of outstanding gifts. But there is a darker and harder element in Thérèse’s account, detectable to close readers who take the Story of A Soul seriously. Pope John Paul I noted it, as does a contemporary biographer, who said that people who go to St. Thérèse to discover a flower, grasp a nettle instead.3

There is a subtext, and when I read her, I hear another voice providing a bass rumble under the girlish twitter, a football coach who is growling: “Holiness isn’t the important thing. Holiness is the only thing!” As in football, where hard contact with reality, and repetitive practices are required for victory on the field, so sacrifice and suffering are the necessary components of advancement in the spiritual life. Thérèse only indirectly indicates this; she may be happy indeed, anxious to make her small sacrifices for Jesus, but they are sacrifices nonetheless, and we should not let the girlish charm mislead us. For a continual series of small sacrifices make up the daily life of any Christian in whichever manner of life they live, including especially the average lay person, who has no religious “vocation” in the official sense.

Their Work for the Lord

Newman’s appreciation of the laity begins with his first scholarly work, an attempt to understand the Arian controversy that arose after the Council of Nicea, a work that would have great significance for Newman’s future career. As he saw it, the forces disposed in the controversy were threefold: on the one hand, the bishop, Arias, and the Emperor in Constantinople in favor of the Arian reduction of Christ to less than full divinity; then there were the Bishops whose resistance to Arias’ theology was lukewarm, and finally, the main focus of resistance and upholder of orthodoxy was St. Athanasius, along with large portion of the laity who supported him.

The episcopate … did not, as a class and order of men, play a good part in the troubles consequent upon the Council [of Nicea]; and the laity did. The Catholic people, in the length and breadth of Christendom, were the obstinate champions of Catholic truth, and the bishops were not.4

Newman’s book, The Arians of the Fourth Century, consisted of over 200 pages of dense text explaining every apparent opinion on the Trinity extant in the 4th Century. Such books are usually forgotten within a decade, but Newman’s history remains of interest. Newman provides an interpretation, i.e., that the ancient controversies are, in fact, the story of a threat to the orthodoxy of Christian doctrine, and to the communal coherence of the Church itself, from which the escape was providential. More exactly, there is also his focus on the role of Athanasius, and imputing to the laity a prophetic role in this particular circumstance. Newman’s appreciation of the place of the lay people within the Church would be expanded later in his career in his foundation of a Catholic university in Ireland, his encouragement of a lay Catholic journal, The Rambler, and in his essay, “On Consulting the Faithful on Matters of Doctrine.” The Catechism echoes Newman’s point, stating that the laity has priestly, kingly, and prophetic roles to play within the Church. One outstanding reflection of the lay prophetic office can be seen today in the widespread opposition to the abortion regime in America, which arises mainly from the laity, in the pro-life activities within individual parishes which are self-organized, and by the Knights of Columbus, without direct encouragement from pastors and bishops.

Newman’s scholarly writings appeal to a wide audience because of their intellectuality, as well as their spirituality. They are aimed principally at college educated people, and beyond that, to people with some knowledge of the history of religion, and the interaction between religion, politics, and general culture. It is important for highly educated people, who tend toward a degree of critical skepticism, to see that a man of Newman’s erudition and intellect can be an orthodox believer, and, perhaps, then to be motivated by Newman’s own devotion to the truth in order to pursue holiness and spiritual advancement. And people with college level education, and curiosity enough to pursue religious matters, are often influential in the Church, and in the general culture, and within their own personal ambit. But what about the majority of Christian believers who have not the degree of education, or accomplished intellect, to be able to read the monographs of one of the great minds of the Victorian era? For them (and for the educated as well), there is the “little way” of St. Thérèse.

Given that Thérèse’s mission was to bring souls to Jesus, how was she to accomplish this as a nun enclosed in a small convent in France? Her spirituality was so pure, and yet without the sheen of zealotry, and so unforced and outgoing, that it attracted attention from her fellow nuns. But how was her message of the “little way” to escape the walls of her convent? Newman wrote many books, but Thérèse only one. The Story of a Soul was the answer to her dilemma, for by this means, she, and her spiritual doctrine, would become known to the world.5 It is noteworthy that her book came about without her intending it, for each of its separate parts were written at the explicit request or direction of her superiors at the Carmelite convent in Lisieux. Thus, the structure, as well as the appearance of the book, may be seen as providentially arranged.

The Story of a Soul comes in three parts: the first eight chapters are an account of her growing up; chapters nine and ten continue her life story as she enters and now lives in the convent; the final chapter, eleven, is an account of her inner spiritual life—her consortium with Jesus. The first eight chapters give force to the description of the “girlishness” of her book, and even in the later chapters her language is conventional, and when original, somewhat clumsy, as when she compares Jesus to an elevator that lifts the believer upwards without any effort of his or her own. This criticism, of course, would not discomfort her because, as she repeatedly said, she was the weakest, and of least account, in the kingdom of God. In any case, we have to explain the influence, as well as the origin, of Thérèse’s little book. As originally written, i.e., as it came from Thérèse’s hands, it was a somewhat scattered collection of disparate parts which was then edited by her biological sister, Pauline, who also was professed at the convent. As a result, attempts were subsequently made to get a hold of Thérèse’s original manuscript, and translate it without the sisterly editing, which smoothed out, and somewhat homogenized her text. Father Ronald Knox was the first to do so (The Autobiography of St. Thérèse), but other religious scholars have followed, so that there is now a complex scholarly apparatus attached to the scattered writings of an enclosed nun who died young.6

It is almost amusing to read Thérèse’s continual self-criticisms, since she was surely aware of the great gift of holiness that God had given her; so what is happening here? The answer is that as holy people, like Thérèse, acquire greater degrees of sanctity, and become closer to God, their own unworthiness becomes increasingly apparent to them. Francis of Assisi, when he called himself “the worst of sinners,” is not comparing himself to the average man, or even the average Catholic man, which comparison is obviously so much in his favor. No, he is comparing himself to Jesus. Teresa of Avila is not comparing herself to the average woman, or even the average nun, when she refers to herself as a worm. Rather, she is comparing herself to Jesus Himself. In these comparisons, the least venial sin, or wayward inclination, by the holy person seems to them a vast insult to God.

In making the claim that lay people can, and even have the responsibility to try to attain spiritual advancement in the same manner and degree as conventual nuns and ascetic monks, one element clearly is lacking. The necessary sacrifices and disciplines are as it were “programmed” into the lives of nuns and monks by means of a rule that requires getting up at certain times, eating at certain times, so many hours of sleep, fasts and prayers, many prayers. This was the life that Thérèse lived from the age of 15. But where then do lay people get the same degree of discipline, the opportunity as it were to make such lifelong sacrifices? As it happens, the opportunities are many, once the lay person is alive to it. For the daily events that come about as a person performs their daily responsibilities—whether at school, the job, or family life—the frustrations, the oppositions, personal slights, the continual effort required to get through one’s day, are all opportunities for sacrifice, once they are given up to Jesus, and performed, as it were, in the sight of God.

Newman’s doctrine is essentially the same as Thérèse’s, although expressed as precisely as a college tutor would, but no less forcefully, i.e., that holiness is found in the doing of one’s daily duties in life. Here are excerpts from one of Newman’s personal prayers:

Teach me, Lord, to be sweet and gentle in the events of life, in disappointments, in the thoughtlessness of others … Let me put myself aside, to think of the happiness of others, to hide my little pains and heartaches, so that I may be the only one to suffer from them. … Teach me to profit from the suffering that comes across my path; let me use it that it may mellow me … May my life be lived in the supernatural, full of power for good, and strong in its purpose of sanctity.

On Lay Spirituality

What do Thérèse and Newman have in common in regards to their doctrines of lay spirituality? First, that they have such a doctrine that extends the option of spiritual advancement, in a positive and direct sense, to lay people. This is new enough in its way to require notice. Thérèse and Newman readily give an answer to the question: “What is the general means by which lay people may acquire holiness?” Thérèse’s and Newman’s answer is “all you need is love,” that is love expressed in doing one’s daily duties in life. In Thérèse’s case, we have photographs of her doing laundry, and on knees, washing the floor, while in her autobiography, she details her attention she paid to an elderly nun whose irascibility she had to learn to overcome, and ignore; that is, nothing heroic, but doing each day what daily living required. Doing such duties without seeing praise or notice, suppressing resentment, not overlooking details because no one would notice, doing these things for the love of Jesus, was the essence of her “little way” to holiness, a way that is available to all.

Second, that the means to holiness for lay people rests not in the events and characteristics usually associated with the great saints, e.g., no ecstasies, no levitations, and no miracles, no foundations of religious orders, and no martyrdom, are required (although many lay Catholics and religious have been murdered for their faith, in this century, and the last). And it is notable in this regard that the careers of both Thérèse and Newman were not characterized by such things either, i.e., no reports of levitations, ecstasies, or miracles, but then none have been associated with the recently canonized St. John-Paul II, and Mother Teresa (except for the posthumous healings needed for canonization). Thérèse’s work sets off a firestorm of interest and hope to many millions because of the opportunity to serve God in daily living. Newman leaves behind a vast library of Christian thought that inspires and intrigues scholars, and others, to this day. “By their works ye shall know them,” the master of the spiritual life says.

Thirdly, the question arises, how can we know that lay people have found holiness if it requires only the daily doing of one’s unexciting, and seemingly inconsequential, daily duties? “By their works you shall know them,” the Master of the spiritual life says. The outcomes tell all. The positive and visible effects of the lives of holy people are often apparent in the response of people around them; the presence of holy lay people can also act as an encouragement to parish priests, deacons, and others, who can see the positive effects of their daily efforts. The holy lay people become known for their activities in the parish, or for their involvement with pro-life, or social justice efforts, but especially for their attachment to the people they come in contact with, including the perpetually angry, the ignorant, and the haughty. Their concern for the hurt, the poor, and the vulnerable, as they encounter them; their devotion to the Mass, and daily prayers. Holy people may have simply, by their mixing with other people, a calming and encouraging effect by their presence, which are the actual effects of invisible graces. In this way, holiness infuses the whole Church “from the bottom up.”

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1994, Sections 897-948, “The Lay Faithful”. In the documents of the Second Vatican Council, “Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity”; Nov.; 18, 1965. See also two papal documents on the laity, Pope Paul VI, “Decree on the Apostolate of Lay People”; Nov. 18, 1965, which is a separate document from the Decree of the Council and includes a section entitled, “The Spirituality of Lay People”. John-Paul II, “Christofideles Laici” which contains two sections, (16) “Called to Holiness” and (17) “The Life of Holiness in the World;” Dec. 30, 1988. ↩

- Cardinal Newman’s Best Plain Sermons, ed. Vincent Blehl, S.J., with forward by Muriel Spark; New York, Herder and Herder, 1964; pp. 33-43. Besides reprints of his sermons, most of Newman’s other writings have been republished. There is also a huge volume of writing about Newman, but see Fr. Ian Ker’s recent biography and The Oxford Movement by James Church, a reprint of an account by one of Newman’s contemporaries. ↩

- Kathryn Harrison, St. Thérèse of Lisieux; New York, Viking, 2003; pp. 2,4. ↩

- The Arians of the Fourth Century; Note 1, “The Orthodoxy of the Body of the faithful during the Supremacy of Arianism”. This note appears in a later edition, not the first. ↩

- The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieaux: the Story of A Soul; trans. and ed. By John Beevers; Image Books, Garden City, 1957. I am using this edition because it is the best known as opposed to later critical editions. A more recent edition is Story of a Soul: the Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux; trans. By John Clarke, OCD; Washington, 1996. ↩

- Besides Fr. Knox’s volume there are, among many other works, Letters of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux; trans. John Clarke OCD; Washington, 1988; Hans Urs von Balthasar, Thérèse of Lisieux; New York, 1954. ↩

Dr Caiazza:

Very well written/well said!

MH

It’s an incredible gift to us to know that both Terese and Newman shared their lives of faith

in many ways that placed Jesus, front and center. As they evolved, they also shared their

trials and frustrations–none of which deterred them from their hope of glorifying God. By

seeking to find “the holy” in everyday occurrences and acting upon the promptings of the Spirit, they encourage us to try to do the same today. Whatever our station in life, no matter what is happening around us, the mission of the laity remains the same. Thank you to John Caiazza for an essay that inspires the perseverance of our noble and hopeful pursuit.