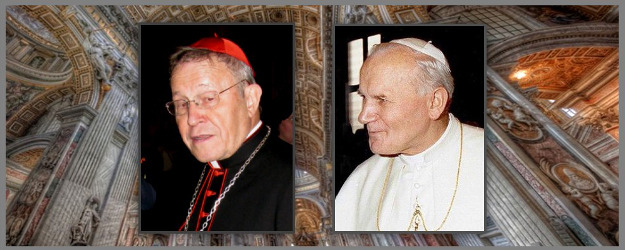

Cardinal Walter Kasper; Pope St. John Paul II.

Ideas have consequences—we well know. My concern here is a series of problematic and closely related conceptions of conscience, human freedom, the moral qualification of human acts, and progress in moral living that might be operative in the minds of not a few of the world’s Catholic bishops as they prepare to participate in October’s much anticipated 14th General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops on “the vocation and mission of the family in the Church and in the contemporary world.”

Most readers of this journal are already familiar with the controversy surrounding the Synod. At the heart of all the commotion are a series of questionable pastoral proposals regarding the possibility of communion for the divorced and remarried put forth by Cardinal Walter Kasper (proposals he has been circulating for over two decades). Controversy was heightened when, at the halfway point of last October’s preparatory synodal gathering of select bishops and cardinals (the “extraordinary” synod of bishops), a “midterm report” seemed to suggest that, not only was much up for grabs in the Church’s pastoral approach to the divorced and remarried, but also that the Church ought to affirm the “constructive elements” present in the relationships of cohabitating persons, and to “value the sexual orientation” of “homosexual persons.”

Shortly thereafter, the most comprehensive and authoritative response to Kasper’s proposals to date was published in a volume edited by Fr. Robert Dodaro. Remaining in the Truth of Christ counted five cardinals among its co-authors, and dealt a blow of considerable, scholarly weight to his specific proposal that the Church embrace the practice of oikonomia, whereby the Orthodox Churches, under certain circumstances, give their blessing to a second (civil) marriage of the baptized after a period of penance.

The midterm report proposals were considerably tempered, a few weeks later, with the publication of the final report of the extraordinary synod (relatio synodi). This then became the basis for Synod 2015’s “working document”—the Instrumentum Laboris—released last June.

Now, for all the speculation that Synod 2015 could lead to doctrinal “Armageddon” regarding the nature of marriage, the indissolubility of the marital bond, cohabitation, and same-sex unions, we really must remain confident that the Holy Spirit is constantly assisting the Church, and particularly the successor of Peter. Our concern, rather (and our prayerful intercession), should be for those bishops who toy, not only with Kasper’s proposals, but with the problematic propositions here explored, and who do so for, perhaps, the simple reason that they lack the moral courage—in increasingly hostile environments—not only to teach the truths entrusted to them, but to persevere in believing those truths themselves.

The true teaching at stake here goes much deeper than questions of how to deal pastorally with the divorced and remarried, or whether the Church can, or cannot, declare some marriage bonds dissolved. It involves our understanding of underlying anthropological presuppositions, namely, our concepts of conscience, freedom, the moral qualification of human actions, and of the nature of human moral progress.

Wobbly thinking on all of these four counts was more than present in the October 2014 synod midterm report. We might begin by asking, for instance, why its authors felt so compelled to explore avenues for an ecclesial “affirmation” of the “positive elements” to be found in “faithful” cohabitating relationships, and in same-sex unions, and to “value” the sexual orientation of “homosexual persons.” There is much more behind this than mere acquiescence to a secular culture that demands such affirmation.

To fall short of such an affirmation—in the mind of not a few theologians and bishops—would be to remain beholden to an impersonal ethic of rule-following, an ethic putatively in tension with the lived reality of these individuals, and incompatible with a sound pastoral sensitivity and personalistic approach to morality. Their contention (and Cardinal Kasper’s, in particular) is that this alleged moral intransigence is incompatible with the Church’s understanding of the flexibility of positive law (technically referred to by the Greek term, epikeia), which needs to be malleable in view of the applications and adaptations that could not be foreseen by the framers of such laws.

That’s all fine and good as far as positive law goes. But not all moral norms arise from positive law. To suggest that all moral norms should be subject to such adaptation and flexibility is not only to conflate positive law with the whole of moral normativity, but also to suggest the nonexistence of exceptionless moral norms, a stance incompatible with perennial Catholic moral teaching. Underlying this moral theological quagmire are, first of all, two problematic notions: a conception of conscience as personal decision, and a dualistic notion of human freedom.

The view of conscience as personal decision conflates the genuine judgment of conscience (which can and should arise independently of one’s decision-making capacity) with mere moral opinion. In the Catholic understanding of conscience—based firmly on the thought of Thomas Aquinas (who in turn, it must be pointed out, was simply being a student of human psychology here)—conscience does not create moral norms. It is not literally autonomous—a law unto itself. Rather, conscience is the manifestation of human practical reason, guiding an individual to be fully reasonable, to embrace and be harmonious with a perceived ordering of personal choices and actions which most fully respects the integrity of the human goods involved, and is most conducive to one’s genuine flourishing, and that of others.

Aquinas held that conscience, in the strict sense, was as an act of human reason—a judgment—that can precede, accompany, or present itself subsequently to choice. Conscience is reason’s awareness of a choice or action’s harmony, or disharmony, with the kind of behavior that truly leads to our genuine well-being and flourishing. The genuine judgment of conscience stands before us, so to speak, independently of our feelings and opinions regarding our chosen actions.

In fact, a person might make “decisions” based on “opinions” about how to achieve the good without ever getting in touch with the genuine judgment of conscience on such matters. In the contemporary view, conscience is essentially creative, autonomous, a law unto itself, settling personal moral matters by way of autonomous decision. Such a conception is simply incompatible with the anthropology of the human person that undergirds the Church’s received moral teaching.

Hand-in-hand with this faulty notion of conscience goes a faulty notion of freedom and of moral self-determination. In this view, human freedom actually operates on two levels, one conscious—the state in which we make everyday choices—and the other deeper, transcending conscious awareness, wherein we find our true self-worth, and determine ourselves as moral beings, where we have presumably made a “fundamental option” for, or against, God. Seemingly, however, in this account of freedom, and barring stark evidence to the contrary (such as having a zest for acts of genocide), everyone’s fundamental option is in the “right” direction from the get-go of one’s moral life: the radical orientation of one’s whole life is toward God, as evidenced by the collective whole of one’s “right” moral choices in everyday life, the rightness of which is primarily assessed by the motives that inform them.

Given this two-tiered understanding of personal freedom, a person can licitly, at times, choose what these theorists would term as “pre-moral,” “physical,” or “ontic” evils (such as abortion, adultery, euthanasia, and the like), albeit, reluctantly and regrettably, and bring them about. However, if brought about for personally valid and substantial reasons, such choices and actions can be “right” moral options. Nor do these choices have an impact on the core, or fundamental, moral goodness—the fundamental option—of persons who thus operate as long as their choices are buoyed by right motivations, and a careful moral calculus that has assured a greater net outcome of good consequences over evil, or less desirable consequences in choosing and acting.

I have just described, of course, the conception of human freedom that underlies the set of moral theories broadly characterized as Proportionalism, all of which were definitively refuted in Pope St. John Paul II’s landmark encyclical, Veritatis Splendor.

While Veritatis Splendor thoroughly excoriated this dualistic understanding of human freedom, which separates choices and actions from one’s fundamental option, those ideas—though, perhaps, fallen from the prominence they enjoyed in the 1970s and 1980s—are still influential in the thinking of not a few priests and bishops.

As a consequence of the preceding problematic notions, some bishops have suggested that it can be possible for at least some of the baptized to remain validly (without consequence to their ultimate salvation) and in varying degrees, in communion with the Church even when, in their lifestyle choices (their “conscience decisions”), they openly reject the Church’s perennial moral teachings on marriage, cohabitation, premarital sex, and sexual activity between persons of the same sex.

To be clear, we’re not talking about persons who might engage in such behaviors in a state of invincible ignorance (which the Church’s moral tradition naturally understands can attenuate, and even eliminate, personal responsibility); the idea here is that persons would knowingly engage in such behaviors, acknowledging the inconsistency of such behaviors with Church teaching, even that they are gravely sinful. The further idea is that, in response, the Church would somehow find a way to affirm some degree of soundness in their moral status, and “good standing” with the Church, to use a more common expression. Granted, even the baptized who persistently remain in un-repented mortal sin still remain related to the Mystical Body—but the theologically laden concept of communion cannot adequately describe the nature of that relationship.

To arrive at such a proposition involves, in addition to the preceding notions, a problematic understanding of personal moral progress. Specifically, it requires taking more than a bit of theological license with a principle of Catholic moral teaching, normally referred to as the “law of graduality.” As a moral principle, the law of graduality became fully part of the moral theological lexicon with the publication of Familiaris Consortio (in a paragraph which includes an internal quote of a homily Pope St. John Paul II delivered at the close of the sixth Synod of Bishops, October 25, 1980):

And so, what is known as “the law of gradualness,” or step-by-step advance, cannot be identified with “gradualness of the law,” as if there were different degrees or forms of precept in God’s law for different individuals and situations. In God’s plan, all husbands and wives are called in marriage to holiness, and this lofty vocation is fulfilled to the extent that the human person is able to respond to God’s command with serene confidence in God’s grace, and in his or her own will. (34)

Though not offering a precise formulation of the law of graduality, John Paul II, in the same exhortation, points to the proper Christian context that forms the framework within which this moral principle is to be properly understood:

What is needed is a continuous, permanent conversion which, while requiring an interior detachment from every evil and an adherence to good in its fullness, is brought about concretely in steps which lead us ever forward. Thus, a dynamic process develops, one which advances gradually with the progressive integration of the gifts of God, and the demands of his definitive and absolute love in the entire personal and social life of man. Therefore, an educational growth process is necessary, in order that individual believers, families, and peoples, even civilization itself, by beginning from what they have already received of the mystery of Christ, may patiently be led forward, arriving at a richer understanding, and a fuller integration of this mystery in their lives. (9)

Hence, the law of graduality, properly understood, has its origin in the very reality of human psycho-moral development. As in most areas of human development, so too in the moral sphere, maturity manifests itself through a gradual process—“steps”—toward an ever deeper appropriation of right moral behavior as instantiated in concrete choices and actions. In the Christian context, it articulates the gradual nature of conversion. Genuine conversion places us necessarily on a course that intends steady progress—notwithstanding human weakness and occasional moral failures—toward an ever more consistent and holistic embrace of the truth of Christ’s moral teaching.

But it is vitally important to understand, as noted in Familiaris Consortio 34, that the law of graduality does not imply that either the convert or the Church should craft and validate individualized and autonomous moral norms “as if there were different degrees or forms of precept in God’s law for different individuals and situations.” That would constitute the very perversion of the law of graduality to which John Paul refers—namely, the “graduality of the law.” Converts to the faith are to be led and assisted in appropriating the new moral requirements of life in Christ in progressive steps of gradual conversion and exigency, assuring them of God’s mercy, presence, and grace, safeguarding against their discouragement, accompanying them in a step-by-step renewal of life, but without diminishing the full import of the moral requirements.

The authors of the October 2014 Synod midterm report creatively attempted to import into this sound principle of moral and pastoral theology another notion of “graduality,” which has its own, very distinct theological context, namely, the degrees of relationship of the different Churches and ecclesial communions (and of persons baptized in those communions) to the Roman Catholic Church. This movement of thought may be discerned in number 17 of that report:

In considering the principle of gradualness in the divine salvific plan, one asks what possibilities are given to married couples who experience the failure of their marriage, or, rather, how it is possible to offer them Christ’s help through the ministry of the Church. In this respect, a significant hermeneutic key comes from the teaching of Vatican Council II, which, while it affirms that “although many elements of sanctification, and of truth, are found outside of its visible structure … these elements, as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward Catholic unity.” (Lumen Gentium, 8)

The latter principle regarding degrees of relationship to, or communion with, the Church is articulated in the 2000 Declaration from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Dominus Iesus:

On the other hand, the ecclesial communities which have not preserved the valid Episcopate, and the genuine and integral substance of the Eucharistic mystery, are not Churches in the proper sense; however, those who are baptized in these communities are, by Baptism, incorporated in Christ and, thus, are in a certain communion, albeit imperfect, with the Church. (17)

That formulation, in turn, has its roots in the Second Vatican Council’s decree on ecumenism, Unitatis redintegratio, 22, and—as suggested by the authors of the midterm report—in Lumen Gentium, 8.

However, to import the latter notion of gradualness into the law of graduality is to open up a space for the very “graduality of the law” denounced by Familiaris Consortio. To further suggest that, in such a conflation of meanings, the synod fathers should discover “a significant hermeneutic key” that would enable them to affirm the “positive elements” discoverable in intrinsically disordered behaviors—or to affirm that Catholics who, in deliberate contradiction of the Church’s moral tradition, engage in such behaviors, yet remain nonetheless (albeit “imperfectly”) in a communion of life with the Church—is, not only intellectually dishonest, but also incompatible with the Church’s received understanding of how our deliberately chosen behaviors shape us as moral beings, and affect our relationship with the Author of the moral order. In a word, such a project is—through and through—incompatible with moral truth as consistently taught by the Church, guided by the Holy Spirit. Genuine pastoral concern for men and women on the road of conversion can never be served by infidelity to that truth.

In the end, the world’s Catholic bishops bear the grave responsibility of the diakonia veritatis—the “ministry of truth,” so eloquently elaborated by Pope St. John Paul II in his encyclical, Fides et Ratio (Cf. nn. 49-56). As the same Pontiff observed in his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, “Being responsible for that truth also means loving it, and seeking the most exact understanding of it, in order to bring it closer to ourselves, and others, in all its saving power, its splendor, and its profundity joined with simplicity” (n. 19). Notwithstanding the evident and ever-growing complexity of the manner in which the Church attempts to communicate truth to a postmodern, secular culture, we pray that the world’s bishops, and particularly those participating in Synod 2015, will discover moral courage when faced by the imperative of articulating, teaching, and defending fundamental truths about the human person—that they will exercise the diakonia veritatis.

After reading your legal and moral analysis, I come away with two questions. How do you keep from making God a punitive unloving God in the legal system of the Catholic Church? How do ordinary people come to an understanding of Catholic moral teaching based on philosophical concepts that no longer apply to the context of life experience in the 21st century?

The question of making God punitive and unloving is similar to asking why “parents” are not to be praised for aborting their conceptus to prevent the pains and sorrows the potential child would encounter once born. Men cannot make God other than the Supreme loving, truthful and unchanging Being He is.

Additionally, the ‘Truth’ cannot change based on shifting philosophical concepts or else it is not he ‘Truth’. The philosophical concepts must change to reflect the Truth. Intellectual arrogance can be a terribly difficult thing for smart people. Humility and Faith are necessary in like or greater amounts to the level of intelligence to avoid reliance on human reason alone.

Thank you Father Berg for your article on your article on the actions of man. Conscience is the practical intellect which contains the info given to it. It is not a faculty . The intellect and will are the faculties . St. Thomas Aquinas shows when a person knows the rectitude the person will choose using his faculties either evil (sin) or an act of love. I suggest when at mass an attentive meditation of the Nicene creed. And a study of De Deo Uno and Trini and the Cappadocian fathers where it is shown among other thoughts man is not able to limit God or the divine law.

In the final paragraph of this article, Rev. Berg writes…..”Truth……seeking the most exact understanding of it…..

I am of the opinion that this article singularly fails to do this!

Setting statements of Pope St. John Paul II against documents of Vatican II will create ‘Authoritative’ confusion; no “…profundity joined with simplicity…” is found here.

Stating that Fr Dorado’s book is “… the most comprehensive and authoritative response to Kasper’s proposals…” is factually incorrect, and therefore not worthy of a supposedly scholarly article.

I thank the Holy Sprit for the guidance given to the 2015 Synod session, which united Cardinal’s Kasper, Muller et al.