We do not recall these instances of anti-Catholicism to foster more animosity or violence, but recall them as part of our history, a history that, like so many others, included the targeting of ethnic and religious groups for persecution.

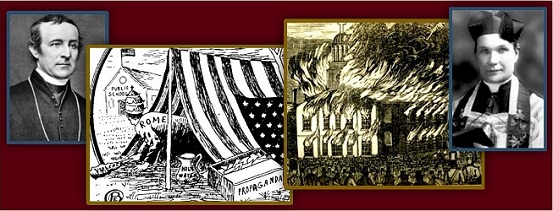

From left to right—Bishop John Hughes, New York, 1844; cartoon from Anti-Catholic book published by the Ku Klux Klan, 1926; Burning of St. Augustine Church, Philadelphia, 1844; Fr. James Coyle, Birmingham Alabama, murdered, 1921.

You have, no doubt, heard the children’s rhyme: “Sticks and stones may break my bones / But names will never hurt me.” That is not exactly true. For in the history of the Church in America, Catholics have been wounded by both physical violence and hate speech. This article will examine episodes of violence against American Catholics, considering the sticks and stones, the broken bones, and the words that encouraged such violence. 1

An Unmentioned History

If the presence of anti-Catholic violence in American history is unknown to many, it is for good reason. We as Catholics do not usually like to talk about being a minority; we do not like to talk about persecution. For generations, our immigrant ancestors and their descendants fought to be considered “100% American,” not “hyphenated” Americans: Irish-American, German-American, Polish-American, or Italian-American. We Catholics have spent decades trying to assimilate into “White, Anglo Saxon, Protestant” (“WASP”) America and have, consequently, downplayed our distinctiveness. We wanted to fit in, and to achieve the American dream—to get good jobs, get a college education, and move to the suburbs.

Aspects of Anti-Catholicism

In considering some episodes of anti-Catholicism, it should be noted that not all violence against Catholics was motivated exclusively by religion. In many cases, religious misunderstanding blended with nativism, and xenophobia, to bring about a toxic reaction to the United States’ Catholic newcomers. Consequently, anti-Catholic groups—that included the Know-Nothing party, the American Protective Association, and the Ku Klux Klan—espoused a form of bigotry, both religious and racially/ethnically motivated.

It should also be acknowledged that most manifestations of anti-Catholicism have not been violent. Much of anti-Catholicism in this country from the 18th century to today was more or less implicit: Protestants considered Catholics “the other.” Protestants often didn’t have Catholic friends, they (and Catholics!) frowned on Catholic-Protestant marriages, and non-Catholics refused to hire or promote Catholic workers. Other times, anti-Catholicism was muted, but real; non-Catholics questioned whether Catholics were even Christians, calling the Church the “Whore of Babylon” (of Revelation 17), and considered the pope the “Anti-Christ,” or taught unequivocally that all Catholics go to hell.

Other times, anti-Catholicism was more overt. In colonial times, laws forbade Catholics from voting, becoming lawyers, and teachers. Catholics, even in Maryland, which had at first tolerated them, demanded a “double tax” on Catholic property; parents could even be fined for sending their children to Europe to be educated as Catholics. 2 The propagation of anti-Catholic ideas manifested itself in various ways: in newspapers, books, and pamphlets, in sermons, in laws, in popular discussion and debate, and, occasionally, in violence and property destruction.

The examples of violence that follow are admittedly among the most pronounced and outrageous forms of anti-Catholicism, but we should not be led to believe that anti-Catholicism was only the experience of a few. As a corrective, it is important to remember that in the 19th century, Catholic-Protestant debates and discussions, often acrimonious, took center stage. They were on everyone’s mind. When the anti-Catholic novel, Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosure—supposedly written by a former nun, telling stories of affairs between priests and nuns, and the murder of the children they conceived—was published in 1836, it became a near overnight sensation. By the start of the Civil War, it had sold 300,000 copies. Historians of this era claim it was among the most widely distributed book in America prior to the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the popular anti-slavery book.

Sticks

Anti-Catholic violence has taken the form of protest against Catholics who were taking their place in the public square. Catholics, it was feared, could subvert the American Republic, especially its democratic processes, and its “public” schools. When Franciscan priests and brothers first came to Cincinnati, Ohio, from Austria in 1844, onlookers did not know what to think of them, walking through the streets in their brown habits. But some recognized them immediately as “Catholic monks,” potential anti-American subversives. In his journal, one of the first Franciscans in Cincinnati, Fr. William Unterthiner, described the animosity directed at Catholics, especially priests, in mid-1840s Cincinnati:

The Protestants here are even worse (than in other places in the U.S.); so goes the protest. Today … some people threw wooden sticks at us, and cursed us (as we walked down the street). It is certainly true that a person is free to choose one, or even no religion, but one would still be very mistaken if he believed that Catholics are allowed to live unhindered. 3

As Catholic immigration increased throughout the 1840s and 1850s, concern mounted that Catholics were taking over America’s public schools—an attempt that would eliminate the Bible (particularly the King James version) from everyday classroom use. The challenge offered by Catholics to “public” schools, that were de facto Protestant schools, brought Catholics and Protestants into frequent conflict.

The so-called “Eliot School Rebellion,” which occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1859, proves a dramatic example. The state law that required the Ten Commandments to be recited (always using the King James Bible) in every classroom every morning, pitted Catholics, who viewed non-Catholics’ Bibles as false translations, against Protestant teachers, parents, and schoolmates. Ten-year-old Thomas Whall, a Catholic, was asked to take his turn leading the recitation of the Ten Commandments. When Whall refused because of his Catholic faith (and his desire to only read from the Douay-Rheims translation, an approved Catholic translation), he was disciplined. Whall had been urged by his parish priest not to recite Protestant prayers, nor read from the King James Bible.

A few days later, when Whall refused again, his teacher struck him with a rattan stick for half an hour until he was bleeding; he refused to give in, and his fellow Catholic classmates cheered him on. The school’s principal demanded that Catholic children, who refused to recite the commandments, leave the school; hundreds left in protest. The “rebellion” helped extend the parochial school system in Massachusetts. Within a year, a Catholic school was established in Whall’s parish with an enrollment of over 1,000. 4

Stones

Not all anti-Catholic violence was physical. Sometimes it resulted in the destruction of property. These episodes represent the ferocity of anti-Catholic violence, though without physical assault or loss of life.

In 1834, an anti-Catholic mob burned the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown, near Boston. The convent school there educated primarily upper-class Protestant girls, and worries of the Protestant elites’ attraction to Catholicism festered. This, together with the rumor of an Ursuline sister being held in the convent against her will, and the anti-Catholic preaching of Rev. Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, incited a riot. 5

An angry mob gathered outside the convent, calling for the release of the sister, but the Ursuline mother superior threatened the crowd: “The Bishop has 20,000 of the vilest Irishmen at his command, and you may read your riot act till your throats are sore, but you’ll not quell them.” The crowd broke down doors and windows to enter the convent, and began to ransack the buildings. The sisters and their students rushed out the back of the convent, and hid in the garden. At about midnight, the rioters set fire to the building, burning it to the ground. Of the 13 men arrested and charged with arson, all but one was acquitted. The governor pardoned him in response to a petition signed by 5,000 Bostonians. 6 Distrust of sisters in convents led eventually to a number of state legislatures proposing “convent inspection laws,” authorizing the warrantless searches of Catholic buildings—convents, monasteries, rectories, and churches—for weaponry, and for young women supposedly seduced into the convent and held against their will. 7

In 1844, two Catholic churches were burned in Philadelphia after it was rumored Catholics were insisting on the removal of the Bible from public schools. The same scene might have been repeated in New York City, but New York’s Bishop, John Hughes, warned: “If a single Catholic church is burned in New York, the city would become a second Moscow,” a reference to the 1812 burning of Moscow in which its own citizens set fire to the city as Napoleon’s soldiers closed in. 8

In 1854, as the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., was being constructed, nine men, associated with the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing party, sneaked up to the base of the monument to steal a stone that had been engraved “Rome to America.” The stone, which was to have been placed inside the monument, along with other stones given as gifts from foreign governments, had been shipped from the Vatican. The men carried the stone to a boat waiting at the tidal basin, smashed it into pieces, and dumped it in the middle of the Potomac River. For them, the stone indicated the threat of the Catholic Church’s takeover of the U.S. government, a much talked about, but very unlikely, threat. The identity of the conspirators was shrouded in mystery; no one was ever convicted of the crime. In 1982, a replica of the stone, given by a priest from Spokane, Washington, was installed in the monument by the National Park Service. 9

The attack on the Shrine of Our Lady of Juan del Valle in San Juan, Texas, provides a final, modern example. In 1970, a non-denominational preacher intentionally flew a small airplane into the church while Mass was being celebrated. No one was injured except the kamikaze pilot who died. While the overall property loss was estimated at $1.5 million, many believed it a miracle that no one else was hurt or died in the tragedy. A new shrine was dedicated in 1980 where the previous church had stood. 10

Broken Bones

Infrequently, physical violence and death were the consequence of anti-Catholicism. In 1853, Pope Pius IX sent Archbishop Gaetano Bedini to visit the U.S. and report back to him on the state of the Catholic Church in America. Because many U.S. Protestants viewed the pope as sinister, and as an enemy of freedom, they blamed his representative.

In Cincinnati, hundreds of protesters marched towards the cathedral where Bedini was staying, carrying signs, a scaffold, and an effigy of the archbishop. The signs read “Down with Bedini!”; “No Priests, No Kings”; and “Down with the Papacy!” Fearing an attack on the residence, the police attempted to turn back the demonstrators. In the ensuing melee, one protester was killed, 15 were wounded, and 63 were arrested. Most of the city’s residents supported the protesters, blaming the police for exercising brutality. Those who had been arrested were released, the charges were dropped, and an investigation of the police commenced. As Bedini continued to tour the country, violent disturbances erupted in Cleveland, Louisville, Baltimore, Boston, and New York. Fearing further violence in New York, Bedini was secretly transported by way of a rowboat to the steamship on which he would depart for Europe. 11

Not long after Bedini returned to Italy, anti-Catholic mob violence struck Louisville, Kentucky. In an incident known as “Bloody Monday” (August 6, 1855), concern about Catholic influence over the electoral process contributed to a mob attack on Irish Catholic neighborhoods, resulting in 22 deaths, scores of injuries, and widespread property destruction. Five people were later indicted; none was convicted.

Religious and racial prejudice combined in the deep South, resulting in the murder of a priest in 1921. Father James Coyle, priest of Birmingham, Alabama, was shot and killed on his rectory front porch. Coyle had performed the wedding of a recent convert to Catholicism, the daughter of a Methodist minister and Ku Klux Klan member, to a Puerto Rican Catholic man. The Methodist minister’s daughter had become interested in Catholicism as a young girl; she converted at age 18 and was received into the Catholic faith by Father Coyle. Only a few months later, Coyle witnessed the girl’s marriage. When her father found out about the clandestine wedding, he confronted Coyle and shot him. The minister was charged with the priest’s murder, but was acquitted by a jury who found him not guilty by reason of insanity. 12 In 2012, Bishop William H. Willimon of the United Methodist Church presided over a service of reconciliation and forgiveness in Birmingham, asking for forgiveness for the role his church had played in the death of Father Coyle. 13

Modern Persecution

In recent years the threat of anti-Catholic violence has surrounded fidelity to the Church’s teaching on marriage and family life. In 2002, Mary Stachowicz, the parish secretary of now Bishop, Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, was raped and murdered. Her killer stated to police that he attacked Stachowicz after she confronted him about his gay lifestyle. Bishop Paprocki, in public addresses on the Church’s approach to same sex attraction, relates the story of his former secretary’s murder in order to condemn all forms of violence based on bigotry. He feels compelled to speak about this form of anti-Catholic violence because it has been almost completely ignored by the media. Bishop Paprocki notes:

A Google search on the Internet for the name “Matthew Shepard” at one time produced 11.9 million results. Matthew Shepard was a 21-year-old college student who was savagely beaten to death in 1998 in Wyoming. His murder has been called a hate crime because Shepard was gay. A similar search on the Internet for the name “Mary Stachowicz” yielded 26,800 results. 14

Mary Stachowicz was also brutally murdered, also the victim of a hate crime, yet, her death went unnoticed. Perhaps, this is a signal that, as in the past, various forms of anti-Catholic violence are still viewed by some as acceptable, or at least, not worthy of notice.

Conclusion: Hate and Love

Why examine these episodes of hate? Why not let them remain hidden in scarcely-read tomes of Catholic history? We do not recall these instances of anti-Catholicism to foster more animosity or violence, but recall them as part of our history, a history that, like so many others, included the targeting of ethnic and religious groups for persecution. Though the Church is often seen in overblown narratives as a perpetrator of violence, responsible for the horrors of the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, and the Holocaust, the Church has also been afflicted by violence motivated by religion. If history teaches us anything, it is that the memory of the past is so often selective.

Yet, this discussion should not end by recalling the role of religious belief in contributing to violence, but should remember the role of religious faith in promoting love. Fundamental to the Church’s teaching is the importance of humanity’s dignity as sons and daughters of the Creator. Violence, if even partly motivated by religion, contradicts what St. John taught us about God—“God is love” (1 Jn 4:8, 16)—a divine love that humanity is called to mirror and extend.

- Treatments of anti-Catholicism in America include: Mark S. Massa, S.J., Anti-Catholicism in America: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (New York: Crossroad, 2003); Ray Allen Billington, The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1964); Katie Oxx, The Nativist Movement in America: Religious Conflict in the 19th Century (New York: Routledge, 2013); Philip Jenkins, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003). ↩

- For a history of Maryland’s colonial era anti-Catholic legislation, see Maura Jane Farrelly, Papist Patriots: The Making of an American Catholic Identity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 188-218, especially 192-194. ↩

- Patrick McCloskey, O.F.M., God Gives His Grace: A Short History of St. John the Baptist Province, 1844-2001 (Cincinnati, OH: The Province, 2001), 6-8; for the complete letter from which this quote was taken, see William Unterthiner to Arbogast Schöpf, May 9, 1845, in Patrick McCloskey, O.F.M., “Letters of Fr. William Unterthiner, O.S.F. (1844-1846): Founder of the St. John the Baptist Province” (M.A. thesis, St. Bonaventure University, 1979), 113. ↩

- John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), 7-11. ↩

- Nancy Lusignan Schultz, Fire and Roses: The Burning of the Charlestown Convent, 1834 (New York: Free Press, 2000); Katie Oxx, The Nativist Movement in America: Religious Conflict in the 19th Century (New York: Routledge, 2013), 25-52. ↩

- Jeanne Hamilton, O.S.U., “The Nunnery as Menace: The Burning of the Charlestown Convent, 1834,” U.S. Catholic Historian 14, no. 1 (Winter 1996): 35-65; quote at 42-43. ↩

- Robert P. Lockwood, ed., Anti-Catholicism in American Culture (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2000), 38. ↩

- Oxx, The Nativist Movement, 53-82; quote from John Hassard, Life the Most Reverend John Hughes, First Archbishop of New York (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1866) 276. ↩

- Oxx, The Nativist Movement, 83-110. ↩

- Daisy L. Machado, “Borderlife and the Religious Imagination,” in Sarah Azaransky, ed., Religion and Politics in America’s Borderlands (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013), 88-89. ↩

- David J. Endres, “Know-Nothings, Nationhood, and the Nuncio: Reassessing the Visit of Archbishop Bedini,” U.S. Catholic Historian 21, no. 4 (Fall 2003): 1-16. ↩

- Sharon L. Davies, Rising Road: A True Tale of Love, Race, and Religion in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↩

- North Alabama Conference of the United Methodist Church, “Bishop Willimon to lead Ash Wednesday Service of Repentance and Reconciliation,” February 14, 2012, http://www.northalabamaumc.org/news/detail/1089. ↩

- “Bishop: Catholic Mom Murdered by Gay Man ‘Died a Martyr for Her Faith,’” July 11, 2013, http://cnsnews.com/news/article/bishop-catholic-mom-murdered-gay-man-died-martyr-her-faith. ↩

I’d also recommend “Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574-1783” by Robert Emmett Curran from CUAP, which I just reviewed on my blog:

http://supremacyandsurvival.blogspot.com/2014/08/book-review-papist-devils.html

Curran looks at Catholics in the British West Indies and Nova Scotia as well as Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania in the colonial era through the American Revolution.

Thank you father Endres for this writing . In that history of violence upon catholics there was the forgotten amendments to the US constitution of james Madison the first which was freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom of peaceful assembly, and no established religion but the free practice of religion. By some in the US this continues to be ignored . I overheard some persons state that the Catholic church was founded on fear. I told that was incorrect but that Jesus began the Church in love of God and neighbor assisted by his grace. Ignorance is not bliss ,it is a lack of truth and divine love.

On Vacation, once attended a daily Mass at a small town near Acadia National Park. The Parishioners there recounted how, when the first Priest came, to the first Catholic Church, the townspeople took him outside the town, tarred and feathered him, and then burnt the Church down… My family once lived in a small town in Indiana – that state has a very large KKK contingent, and they hated Catholics. We had quite a number of attacks, before we finally moved. A farmer threw a steel cable over the door handles of the family car, connected it to his tractor, and yanked the handles off. What was worse, was that we children were standing there, and the cable recoil could have killed us. And how’s this for friendship: We young kids were somehow (wrongly) invited to a Protestant Church picnic. When they discovered I was Catholic, they called all their kids up to their tables, leaving me alone in the playing field. When I turned around, they were all standing there, staring at me with hostility…There was one young woman, however, who came and comforted me. I often wonder what happened to her….

The Crusaders wanted to make the Holy Land free again for pilgrims; they of course knew they would be attacked, and came prepared to defend themselves. Islamic conquest spread rapidly for several hundred year from the lifetime of Mohammed, eventually into Western Europe, even St. Peters was sacked by their pirates. I don’t think the religious motivation of the Pope, and sincere Crusaders contradicts what St. John wrote about love. Pope Francis just said something recently about stopping ISIS. What do you think of the comparison father?

John — Yes, I would draw a distinction between violence — especially the kind of isolated, hateful acts described above — and the kind of coordinated, armed defense you mention — which can be morally just and thereby would not conflict with St. John. The Catholic just war tradition provides a starting point for the discussion, but of course it does not neatly apply to modern warfare.

And now we are not longer “different”. I guess they won. Modernism and the changes to the Mass and Catholic culture since mid-twentieth century have made some of us almost indistinguishable from protestants.