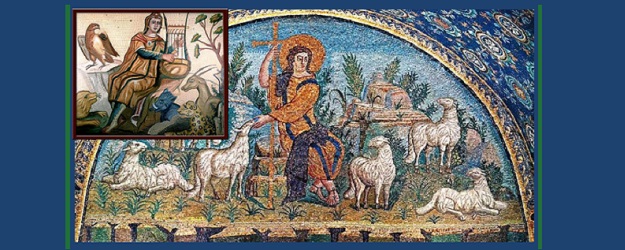

Large mosaic (artist unknown) from the Good Shepherd mausoleum of Galla Placida, Ravenna, Italy, from the first half of the fifth century; smaller mosaic of the god, Orpheus, with harp and animals.

God’s manifestation of his beauty/glory is both a grace, expressing his self-giving generosity, and a call to his joy. Beauty, a relational aspect of created or uncreated excellence, is always the self-manifestation or communication of excellence.

Our enjoyment of God’s radiant beauty/glory evidences our communion, community, and communication with God. Our joy/enjoyment of God’s beauty/glory is the created effect of the divine generosity sharing itself with us. Our joy or enjoyment is being “effected” or caused by uncreated Joy, or Happiness Itself. It evidences the active presence and vitality of a joy that this world can neither give nor take from us. The absence of such joy evidences the failure of Happiness Itself to take effect in our lives.

Joy evidences our “seeing” and “hearing” the beauty/glory of God in our relational existence. It is evidence that we are in touch with the truth, goodness, and beauty of the gift of life. Joy, or enjoyment, is the fruit/effect of the Holy Spirit’s active presence in our lives.

Christian faith is the eye of love that enjoys the vision of God’s beauty/glory. Christian contemplation is the look of love that is happy to see God in all things.

God loving the soul, and the soul loving God; God giving himself to the soul, and the soul giving itself to God; God abiding in the soul, and the soul abiding in God; God working in the soul, and the soul working with God; God enjoying himself in the soul, and the soul enjoying itself in God—all this is expressed in the word “charity.”

How many Christians ever think of enjoying God? Yet, this is one of the scriptural conditions laid down if we want our prayers to be heard: “enjoy the Lord, and he will give you the desires of your heart” (Psalm 37:4).

St. Catherine of Siena teaches that there is no way to attain to the fullness of Christian life except through delight in the Lord: “this is the way, and all must pass through it who want to come to perfect love” (St. Catherine of Siena, Dialogue, ch.63).

The official prayer of the Church often bids us to seek the joy of the Lord. One of the old prayers for the “Prime” (the first hour of the Divine Office) said: “in this hour of this day, Lord, may we be filled with your loving kindness, so that we may rejoice the whole day long, delighting in your praise” (From the Dominican Breviary).

Of course, our delight in the Lord develops and matures; its emotional content may give way to something quieter and more austere. When the eyes of the heart are opened by the Spirit of God’s love, we enjoy the beauty of God’s presence with an unshakeable delight in him for his own sake. God gives us his Spirit precisely to stir us to seek, and to enjoy, the true beauty and goodness of his Spirit. Through the gift of his Spirit, we see the beauty of the Lord, giving his life for his friends (John 15:12-13).

God’s Grateful and Joyful People

Vividly aware of God’s manifest blessing in their past, expecting greater blessings still to come, the Jews practiced a joyful religion. “I will go to the altar of God, the giver of triumphant happiness” (Ps 42:4). No matter what might befall them, God’s mercy and power would protect them. “What though the fig tree never bud, the vine yield no fruit … still will I make my boast in the Lord, triumph in the deliverance God sends me” (Heb 3:17-18). That they are God’s chosen people is the foundation of their confidence, and the psalmists ecstatically hymn the fact (Ps 99:3; see Isa 42:23). “Learn that it is the Lord, no other, who is God, his we are, he it was who made us; we are his own people” (Ps 99:2).

Because God has so cherished them, Israel felt an obligation to rejoice; their joy in their God was a due they owed him. “Pay to the Lord the homage of your rejoicing” (Ps 99:2). Not to do so was a punishable offence. “Because you would not obey the Lord your God in happiness and content … you must learn now to obey those enemies the Lord will send to conquer you” (Deut 28:17; see Ps 80:1). The joyfulness of the religion of Israel is plainly apparent from even the most hasty perusal of Israel’s hymn-book, the psalms. Some of them are paeans of joy. “Come, friend, rejoice we in the Lord’s honor; let us cry out merrily to God” (Ps 94). “The Lord reigns as king; let the earth be glad in it, let the isles, the many isles, rejoice” (Ps 96).

Nor were the thoughts of Israel wholly on the past. Greater things lay in the future. The rich promises of the prophets were yet to be fulfilled. “See where I create a new heaven and a new earth; old things shall be remembered no longer, have no place in our thoughts. Joy of yours, pride of yours, this new creation shall be; joy of min, pride of mine, Jerusalem and her folk create anew” (Isa 65:17). The great King was still to come: “Even wider shall his dominion spread, endlessly at peace; he will sit on David’s kingly throne, to give it lasting foundations of justice and right” (Isa 9:7; see Jer 39:21). Israel rejoiced not only in the recollection of God’s benefits, but in the anticipation of yet greater benefits which would arrive with the advent of the Messiah.

From its roots in Genesis, the flower of Christian joy has pushed its way into the air and light of the New Testament. There it buds, expands, and blooms. “Joy and gladness shall be yours” (Luke 1:14) says the angel to Zachary, telling of the conception of the forerunner. “My spirit has found joy in the Lord,” cries the mother of the Messiah when the conception of the Messiah is announced. “I bring you good news of great joy” says the angel heralding his birth (Luke 2:10). The Magi, led by his star to his dwelling place, are “glad beyond measure” (Matt 2:10).

Joy in the advent of the Messiah is the keynote of Luke’s infancy narrative. It is adorned with three canticles, hymns of praise which burst from the lips of Mary, Zachary, and Simeon, as they see Israel’s hopes moving to fulfillment, and greet the “Son of the most High,” the “scepter of salvation,” and the “light which shall be a revelation to the gentiles.” This note of joy in the advent of Christ, which dominates the first chapters of Luke, recurs through his Gospel, “The whole multitude rejoiced over the marvelous works he did” (Luke 13:17).

Zaccheus “came down with all haste and gladly made him welcome” (Luke 19:6); “and the apostles went back full of joy to Jerusalem” (Luke 24:52).

Matthew and Mark make it equally clear that the Gospel is the “tidings of great joy.” The essential message of Matthew is that the Messiah has established the kingdom of heaven on earth, and that its citizenship is available to all nations. The last verses of his Gospel give lucid expression to this triumphant accomplishment of the kingdom and its unshakeable permanence. “All authority in heaven and earth has been given to me … and behold I am with you all the days that are coming, until the consummation of the world.”

Mark’s Gospel highlights the miracles of Christ. Like the deeds of the Jewish Scriptures, they bear witness to God’s presence, his power and his love. Their narration is intended to evoke a joy in the hearer like that of those who were healed by Christ.

John’s Gospel presents the Savior in terms of light and life. The aura of joy that Christ brings with him is rendered explicit by the Baptist, “the bridegroom’s friend who stands by and listens to him, rejoices too, rejoices in hearing the bridegroom’s voice; and this joy is now mine in full measure” (John 3:29). Christ promises permanent joy, “One day I shall see you again, and then your hearts will be glad, and your gladness will be one which nobody can take away from you” (John 16:22).Here it is revealed that we are called to share Christ’s own joy. “All this I have told you, so that my joy may be yours, and that your joy may be complete” (John 15:11). The Acts of the Apostles show us the fulfillment of this promise. Exhilarated by the resurrection of Christ, and the descent of his Holy Spirit, the apostles and their converts “shared their food gladly and generously” (Acts 2:46). Persecution cannot extinguish their joy. Their message always brings joy to those who accept it. Philip’s mission to one of the cities of Samaria evokes great rejoicing in that city (Acts 8:9). The eunuch from Ethiopia encounters Philip, is instructed and baptized, and goes on his away rejoicing.

The apostles in their letters recognize it as their mission to bring joy, “If we are writing to you now, it is that your joy may be complete” (1 John 1:4). Paul invites the Philippians to share his joy (Phil 2:17), and to rejoice in the Lord always (Phil 4:4; see 3:1). Joy is a hallmark of Christian faith, hope, and love, “The kingdom of God … means rightness of heart, finding our peace and joy in the Holy Spirit” (Rom 14:17). Paul prays “May God fill you with all joy and peace in your faith, so that in the power of the Holy Spirit you may be rich in hope” (Rom 15:13).

Sharing God’s Joy and Reflecting God’s Beauty

A survey of the Mass prayers for the Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany seasons confirms the principle that the lex orandi is the lex credendi for the theology and spirituality of beauty. The prayers and scriptural readings are replete with the vocabulary expressing the community of faith’s experience of the glory of the Father in his Incarnate Son enjoyed through the gift of their Holy Spirit. The Incarnate Son irradiates the splendor of the Father whose Spirit enables the community to rejoice and praise the Triune God for this transforming experience.

The prayers and readings link the enrapturing beauty of the Father’s self-gift in his Son, and their Holy Spirit, to its transforming effect on their lives, making the unlovely lovely, enlivening the lifeless, transforming the deformed, enlightening those in the darkness. The implication is that the Triune God does not manifest his beauty for mere show, but to share it with all who are happy to be transfigured by it. The beauty of God’s love is the transfiguring power of God’s self-giving life. It is in this sense that we can truly affirm that Beauty (God) saves the world.

God is true life, love, goodness, generosity, beauty, and happiness itself. The community of faith cannot experience God without experiencing truth, life, love, goodness, generosity, beauty, and happiness itself: the fullness of life. It cannot experience a part of God without experiencing all of God, because God’s self-giving is total: God gives all of himself.

Consequently, a true theology and spirituality of beauty cannot abstract God’s beauty from the reality or truth of his life, love, goodness, generosity, and happiness. God is One. We cannot experience God’s beauty as an abstraction from all that God is. God’s beauty is the beauty of all that God is: his true goodness, wisdom, love, generosity, happiness. Consequently, a theology and spirituality of beauty must correct the tendencies to imagine God’s beauty in terms of appearances, or an attractiveness separate from his life. God is not a beautiful object in a world of beautiful objects, no more than God is a reality in a world of other realities. God is existence itself giving existence to whatever has existence as a “given.” The world consists of mathematical givens for people who do not believe that God exists; for those who do believe, all the givens of human experience presuppose a Giver.

Spirit – life – creation – new creation – inspiring persons vs. dispirited or lifeless persons – having a life vs. not having one – enlivening others vs. draining them as the living dead—all are themes, or topics, that enter into the spirituality and theology of beauty.

The fruits of the Holy Spirit evidence the life of the Holy Spirit produced by a tree that does not produce fruit for itself, but to nourish, enliven, sustain, and delight others with its good taste. The Spirit is where it acts (Aquinas). The tree and fruit symbolism expresses how it acts: generously giving life, support, joy, delight, pleasure to others. God’s beauty cannot be abstracted, or separated, from God’s life and activity. By the same token, the kingdom of God is where God/Spirit/Life Itself governs rules/governs minds and hearts. Just as the Spirit is where the Spirit acts, the kingdom is where God/the Spirit governs. In both cases God/Spirit manifests the beauty, radiance, splendor, joy, excellence of his life.

A theology and spirituality of beauty must treat of both the kingdom of God, and the fruits of the Holy Spirit, apart from which there is no Christian experience of God’s beauty. Joy, as the fruit of the Holy Spirit, is infallible evidence of God’s active and transforming presence in human life. It is a participation in the happiness of the God whom Aquinas calls Happiness Itself (Ipsa Felicitas).

Beauty is the attractiveness of excellence whether material, physical, intellectual, moral, spiritual, or artistic. Excellence inspires and motivates us only when we experience its beauty. There is no achievement in any sphere of human life apart from our experience of its beauty. Our experience of beauty within the various spheres of human experience is indispensable for our pursuit of excellence within those spheres. Our achievement of excellence begins with our motivational experience of excellence.

There is difference between true and seductive beauty: true beauty is humanizing in drawing us to our true fulfillment and happiness; seductive beauty is dehumanizing in drawing us to self-destruction.

Aristotle’s distinction between prudence and cleverness provides the template for the distinction between true and seductive beauty. Both the prudent and the clever have a gift for knowing and selecting the means for the achievement of their ends; however, the prudent discern and select the means that enhance human excellence, whereas the clever discern and select the means that are dehumanizing. The prudent pursuit of true beauty is a virtue; whereas the pursuit of seductive beauty is a vice; the former is humanizing, and the latter is dehumanizing. Our experience of true beauty is liberating and enriching; whereas our experience of seductive beauty is one of our being held captive and made fools of.

Beauty, Leisure, Joy and Festivity

Leon Bloy wrote in a letter to Jacques Maritain, “Joy is the infallible sign of God’s presence.” As one of the fruits of the Holy Spirit, joy is evidence of the Holy Spirit’s presence in our lives. The singing of the psalms expresses the joy of the Holy Spirit among the faithful who praise God.

The Feast or Banquet is a biblical symbol of religious joy. Josef Pieper’s essay, In Tune With the World (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1963) treats of ten ingredients for festivity.

Festivals are extraordinary. They are out of the ordinary, breaking up the routine of daily life. Another ingredient is spontaneity. A third ingredient is that of making the best of a situation. Festivals might revolve around appreciation for something lost, such as Veterans’ Day. Fourthly, festivity, entails a purposefulness which, unlike work, lies purely within itself. A fifth ingredient involves quality over quantity. In the festive state one enjoys the moment so much that one loses sight of passing time. The quality of time overshadows the amount of time. Contemplation is a fifth quality of festivity. Experiencing the meaning of the festival is to experience insights and moments of clarity in an understanding of what has brought people together in harmonious celebration. Renunciation, the largesse of sacrifice, or the refusal of ultilitarian profit, is a sixth ingredient. Abundance is a sixth key to festivity. Worrying about the cost does not reflect the generosity of the festive spirit. Love, a seventh quality, is at the heart of festivity. Where love rejoices there is festivity. Many types of love may come into play: for the family, neighbors, or various social groups. Rejoicing—which can take the forms of singing and dancing—is an eighth characteristic of festivity. Pieper recalls a quote from Nietzsche: “The trick is not to arrange a festival, but to find people who can enjoy it.” Memory also plays an important role in festivity. There are shared memories that bring people together. The final ingredient of festivity is affirmation of the world. Pieper, again, recalls a Nietzsche quote: “To have joy in anything, one must approve everything.” Pieper explains that underlying festivity there must be a “universal” affirmation extending to the world as a whole, to the reality of things, and the existence of man himself.” We cannot accept one thing as good unless “the world, and existence as a whole, represent something good and, therefore, beloved to us.” Ultimately, a feast affirms the goodness inherent within life itself.

Josef Pieper, in his essay, Only the Lover Sings: Art and Contemplation, speaks of the necessity for us to be able to contemplate and appreciate beauty to develop our full humanity. Pieper explains that the foundation of the human person in society is leisure, free time in which one can contemplate, be receptive to being and its beauty.

The reason for joy, although it may be encountered in endlessly concrete forms, is always the same: possessing or receiving what one loves, whether actually present, hoped for, or remembered. Joy is an expression of love. Persons who love nothing and nobody cannot possibly rejoice, no matter how desperately they crave joy. Joy is always the response of lovers receiving what they love. It is more profound than sadness, and our capacity to delight in what is, mostly determines what we are. Pieper teaches us through music, sculpture, and poetry to see the luminous beauty that reflects an origin deeper than themselves.

In my article, “The Ungracious Refuser of Festivities,” (The Bible Today, 38/4, May 2000, pp. 179-81), I note that the elder brother in the parable of the Prodigal Son corresponds to a stock character in biblical literature: the ungracious boor, the churlish lout, the surly and sullen refuser of festivities, who is unresponsive and unwilling to participate in the joyful activities of the community. There is a tragic dimension to such characters, inasmuch as the festivities from which they exclude themselves are the salvation and eternal life that God offers. The biblical tradition associates the refusal of such festivities with misplaced priorities, with the implication of the dire consequences following upon the refusal of people to welcome God’s happiness (p. 179).

The Beautiful Shepherd will Save the World

God created the universe, as Aquinas affirms, to make it beautiful for himself by reflecting his own beauty. Out of love for the beauty of his own true goodness, God gives existence to everything, and moves and conserves everything, intending all to become beautiful within the fullness of his own true goodness. God’s creating the universe to be beautiful implies that God creates it to be delightful; for the beautiful is delightful. Happiness Itself has created us for Happiness Itself . Clement of Alexandria employs Orpheus, the singer and poet of Greek mythology who could tame wild beasts with the beauty of his music, as a symbol of Christ who draws us to himself by the beauty of his divine word of truth (Protr. 1,1-10). This symbolism explains the presence of Orpheus in the Christian art of the first centuries. His image was often characterized by the attributes of the Good/Beautiful Shepherd. The frescoes of some Roman catacombs of the 3rd and 4th centuries depict Orpheus, both according to classical iconographical schemes, and as the type of the Good/Beautiful Shepherd, a Christ figure.

Early Christian figurative art employs the story of Orpheus’ transforming the wild beasts by the beauty of his music, to communicate the meaning of our redemption through the beauty of Christ’s transforming love as the Beautiful Shepherd. The association of Orpheus with Christ as Shepherd is rooted in their transforming beauty.

When John’s Gospel affirms that Jesus is “the Good Shepherd” (In 10:11), the Greek adjective used to qualify shepherd is kalos, the word for “beautiful” and “good,” in describing the beauty of Jesus’ laying down his life for his sheep, and the goodness of that life for them (In 10:11) .The beauty of the Shepherd’s self-giving love explains how Jesus, like God, the Shepherd of Israel, leads, draws, attracts, unites, and sustains his sheep.

The splendor of the Good/Beautiful Shepherd on the cross will draw all persons to himself (In 12:32). The beauty of God’s self-giving love in the crucified and risen Christ saves us by drawing us to itself. This is the implicit truth of Dostoyevsky’s claim that “Beauty saves the world.” Drawn by the transforming beauty of the Shepherd, we leave our ugliness and nastiness behind. The Shepherd metaphor in John’s Gospel contributes to our understanding the transforming impact of God’s beauty in human life. Its association with Orpheus in early Christian figurative art served to inculturate the meaning of Christ for the Greco-Roman world.

Recent Comments