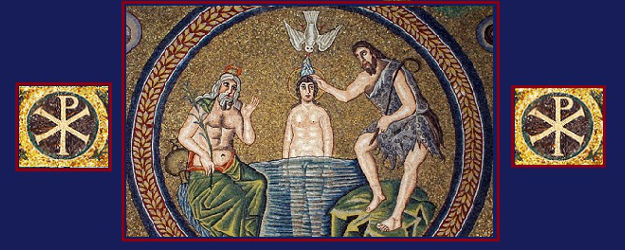

Arian Baptistry, Ravenna, with mosaics of the Greek letters for Christ.

(This title is inspired by Edward Yarnold’s The Awe-Inspiring Rites of Initiation: Baptismal Homilies of the Fourth Century (Slough, Great Britain: St. Paul Publications, 1971), the title of which is based on the common language of “awe” used by the Fathers in regards to the Sacraments; this is particularly evident in the mystagogical works of St. John Chrysostom and Theodore of Mopsuestia.)

_______________

One of the great reforms initiated by the Second Vatican Council was the restoration of the catechumenate, that is, the structured period of initiation for adults being baptized and entering the Church.1 As most will know from its frequent use in parishes, the catechumenate consists of the catechumenate proper (once someone formally expresses his intent to enter the Church), the period of purification and enlightenment during Lent (which prepares the catechumen for initiation), and the period of mystagogy, or post-baptismal catechesis. While many parishes offer mystagogical sessions after initiation (which usually occurs at Easter), many neophytes (the newly-initiated) do not attend. Yet the teaching and catechesis offered during this time is not only important for neophytes: it also has a great wealth to offer even cradle Catholics. I propose that the great treasure of mystagogy not be restricted to merely a few post-baptismal meetings: it should be practiced frequently, in a variety of contexts, in order that the faithful be ever more deeply plunged into the mysteries of the Lord and the Faith through the liturgy and the Sacraments.

According to the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults, mystagogy is a time when “neophytes are…introduced into a fuller and more effective understanding of mysteries through the Gospel message they have learned and above all through their experience of the sacraments they have received.”2 Experience of the Sacraments of Initiation and all the grace that flows from them, as well as the new life in Christ that the neophytes now practice, allows the faithful to delve deeper into what they previously learned through the catechumenate. The mysteries of the Lord and the Faith are not exhausted by any extent of human knowledge and experience, never mind merely a few months of catechesis and preparation. The Sacraments of Initiation are the start of a new life, not the end; they are the beginning of the journey to the New Jerusalem.

For my purposes, I want to concentrate on this concept of mystagogy, though. My source for a definition of mystagogy is the great sea of the Fathers’ wisdom. The word itself has its roots in the concept of mystery, meaning either “to lead the initiate (of the mysteries)” or “to initiate into the mysteries.”3 For the Fathers, the mysteries referred to by this term were primarily the liturgical and sacramental mysteries: after all, this term was first used by the famous Mystery Religions of ancient times to describe the process of their initiation liturgies. Thus the Fathers loved to explain the various aspects of the liturgical rites and to draw out theological, moral, and devotional lessons from them to offer to their listeners. We have a library of examples of sermons or lectures with which they did this: St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s Mystagogical Catecheses, St. Ambrose’s On the Sacraments and On the Mysteries, and St. John Chrysostom’s Baptismal Instructions, among many others. By studying these, we can come to see how the Fathers distributed the wealth of the Liturgy and how we can do so as well. Here I will highlight some of the major aspects of the Fathers’ mystagogy, but a perusal of any of these works would be a great boon as well. Before proceeding further, though, we need a definition of mystagogy to use for this article. So I will say: Mystagogy is post-sacramental “exegesis” of the sacramental rites through sermons based on salvation history, integration into the Church (community), and the task of the Christian life.4

We see first that the Fathers practiced mystagogy via sermons, that is, via preaching. Though there can be a form of mystagogy that occurs through treatises, as would emerge later in Church history, early mystagogy was in the form of sermons. This was due not, I think, to an aversion against treatises, but to a recognition that mystagogy was something needed for all the faithful, not just those with the resources to find and read a liturgical treatise. The way to reach all the faithful (at least those who attend liturgy) is via preaching. Not only that, but it was taking advantage of a popular form of public entertainment during that time: the addresses of orators. St. John Chrysostom frequently laments the fact that his listeners judged liturgies based on the quality and entertainment of the preaching (a problem still prevalent now), yet he also grew adept at using this form to teach his flock. By its homiletic character, then, mystagogy is meant to be available to all the faithful, for the riches of the liturgy, just like the aesthetic riches of ecclesial architecture and ornamentation, are meant for all.

We can also notice that, as in the modern-day restored catechumenate, mystagogy was directed to those who were already initiated into the Church. While prior sermons in the catechumenal process may have been attended both by catechumens and by those already initiated, mystagogy was only for those who were already initiated. Part of this was due to what is called the “disciplina arcana,” or “the discipline of the secret.” The early Christians viewed the mysteries of the Church’s Faith, and particularly of the Sacraments, with great reverence, and they did not want to “throw pearls before swine” and reveal these mysteries to the uninitiated or the Church’s enemies. While this sometimes backfired—as when non-Christians thought the Christians were cannibals because they could not hear the true teaching on the Eucharist—it also strove to keep the sacred things of the Church from being ridiculed by those who were adamantly against the Faith. (We could also say that it protected non-Christians from committing sacrilege and blasphemy: it is worse for them to trample a gift they were given than to not receive it at all.) Another reason for having mystagogy after Christian initiation, though, was because the Fathers recognized the role the experience of the Sacraments and the grace received played in understanding them. No matter how much explanation is provided, an experience has the ability to give a greater understanding; reflection after an experience, too, can shed deeper light on what took place than the discussions beforehand. In addition, the grace received in the Sacraments allows the faithful to reach a new, deeper level of understanding, on top of that given by the experience alone. Thus the Fathers saw that, to grant the deepest understanding possible of these mysteries, mystagogy was needed after the initiation, in addition to preparatory discussions beforehand.

This mystagogy was also an exegetical work. As in traditional exegesis, the four senses of Scripture (literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical) are found, but this time in the texts and actions of the Liturgy, rather than in Scripture. The Fathers often drew on salvation history in their discussions, connecting the Liturgy to various ways the Lord worked in the world. Thus the Liturgy is one of the ways that the faithful are drawn into the drama of salvation history, from the formless void at creation to the New Heavens and New Earth after the Second Coming. Yet probably the main point of the Fathers’ mystagogy is in what we could call the moral sense of the Liturgy, that is, how the Liturgy assists us in living the Christian life in communion with the Church. The Fathers made sure to show how the Liturgy and the mysteries affect the life of the faithful.

The points mentioned above come from those sermons of the Fathers that we would count as mystagogy proper, that is, sermons given to the baptized that were just recently initiated into the Church, usually during the Paschal season. But mystagogy should not be relegated to merely these strict circumstances: it should be incorporated throughout the work of catechesis and preaching. For one, explanation of the Liturgy can inflame a desire to immerse oneself deeper in the Church’s liturgical life. One frequent explanation given for why so many Catholics today no longer take part in this life is because they find it boring or incomprehensible. Well-done mystagogy can assist on both of these fronts. It can thus be an assistant in the New Evangelization. Of course, the mystagogy discussed above only occurs in preaching, so one would first have to convince people to attend church. It might not help give people the push or draw they need to first begin looking at the Faith, but it could draw them deeper once they have begun. Mystagogy also allows the riches of the Liturgy to be distributed to all the faithful, helping those already living their Faith to grow deeper. Though similar statements can be made for all areas of theology, there is so much spiritual wealth in the Liturgy that scholars or faithful who delve into it may know but which the vast number of the faithful may never hear: mystagogy is a way for them to hear of this wealth. Not only that, but it can assist in teaching the doctrine of the Faith, in accord with the classic dictum lex orandi, lex credendi (the law of prayer, the law of belief).

I have first-hand experienced mystagogy done poorly and done well. One of the priests I hear preach regularly is a liturgical historian, and he knows much about the riches of the Liturgy, yet his homilies on the liturgy tend to be somewhat dry and often too enmeshed in the facts of historical liturgical development. Though he often preaches on having our faith affect our lives, he does not usually draw the connections between the liturgy and our Christian lives, and he does not frequently use the four senses of mystagogy mentioned above. On the other hand, I once heard a young priest preach while he was passing through my parish in Weirton, WV. He focused on a text from our (Byzantine) liturgy, “Holy Gifts to holy people,” which the priest proclaims shortly before Communion. The meaning of “Holy Gifts” (the Eucharist) was obvious, but this priest expounded on the phrase “holy people.” By connecting this phrase with how Paul refers to his readers as “saints,” he drew us into the entire history of the holy people of God: we were “the saints who are in Weirton,” just as Paul wrote to “the saints who are in Ephesus” and how Israel was “a holy [or, saintly] people, a royal nation.” This simple phrase from the liturgy highlighted the holiness of the Church and how even the local Church partakes in that holiness, and it impelled us to live up to the holiness with which we were named.

My proposal is that the type of preaching given by this young priest passing through my parish become more widespread, as mystagogy has the ability to open to the faithful the riches of the Liturgy. While the early Church’s firm decision that mystagogy be given to those already initiated is a wise choice, much of modern preaching and catechesis is directed to those who have already been baptized, whether as “cradle Catholics” or as converts. The experience of receiving the Sacraments truly affects all the faithful, even if it is Baptism received as an infant; by mystagogy, Christians can come to know what they have received and to feel that power. (This is one of the ways Baptism in the Holy Spirit is understood: there was only one Baptism, with an indelible mark, but we receive this “second Baptism” when we come to realize the power of that experience, when it truly ignites our being.) Mystagogy can thus be applied to these once-past experiences, as well as to the continuing experiences, such as receiving the Eucharist, Confession, and Anointing of the Sick. Besides the Sacraments, it can be applied even to the entirety of the Church’s Liturgy, all of her public prayers. There is thus an immense treasure-trove of spiritual riches hidden in the liturgy that preachers can draw from, and mystagogy is the process by which to do this.

- This restoration was called for, with little fanfare, by Sacrosanctum Concilium §64, but the result—The Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults (RCIA)—has far outstripped this simple initiation by its effects. ↩

- Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults, no. 245, in Catholic Rites Today, 134. The full explanation of mystagogy is found in no. 244-251, in Catholic Rites Today, 134-135. ↩

- David Regan, Experience the Mystery: Pastoral Possibilities for Christian Mystagogy (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1994), 11; Enrico Mazza, Mystagogy: A Theology of Liturgy in the Patristic Age, trans. Matthew J. O’Connell (New York: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1989), 1. ↩

- Cf. Robert Taft, “The Liturgy of the Great Church: An Initial Synthesis of Structure and Interpretation on the Eve of Iconoclasm,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 34-35 (1980-1981), 59, quoted in Stylianos Muksuris, “Liturgical Mystagogy and Its Application in the Byzantine Prothesis Rite,” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 49, no. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 2004), 296: “Mystery is to liturgy what exegesis is to Scripture.” ↩

Mr. Otto your paper on Mystagogy is excellent showing the Fathers covering liturgy influenced by Scripture. Today many catholics do not know the meaning of catechumen or neophyte or even those words. A person, especially a catholic must be spiritual so he can practice Religion.

My experience with Mystagogy in the RCIA process has, as has yours, provided both good and poor examples in implementation. The poor examples inflicted on the neophytes were painful to observe, reflecting I believe a very poor understanding of the reality of grace, and of the new life begun in Baptism. The period of “Mystagogy” as it was called, was no more than listening to talks given by assorted ministry leaders in the parish, offering the neophytes “opportunities” of where to “plug in” to the “life” of the parish. I don’t know how wide-spread this interpretation is, but I would not be surprised if it were wide-spread. I have observed in many parishes, in my own experience, a very impoverished sense of supernatural grace and the new life in Christ.

I have also observed parishes where there was no period of Mystagogy at all! And everyone involved was happy to end the “RCIA year” early.

The good examples of Mystagogy that I have seen were based on a strong sense of the power of supernatural grace and the efficacy of the sacraments. The neophytes were urged to look for, and to look forward to, the action of the Holy Spirit now in their lives. They were encouraged to be alert to the gentle voice of His instruction, HIs leading. They were cautioned against any falling back into complacency, into lukewarmness, into a neglect of the Gift they had now been given: God was now calling them, personally, into His Life – to express that Life in works of holy charity for the glory of God.

There is a radical difference between Christian life, and pre-Christian life. Neophytes have entered life: they must be taught that fact, and guided toward their own personal example of living that life. God will do in them what only He can do! But if they are surrounded by examples of lukewarmness, or institutional deadness, and if they never hear the Good News of His life, they can well slip off to sleep like many others have done.