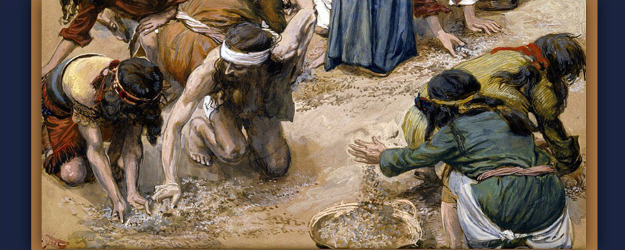

Detail, The Gathering of the Manna, by James Jacques Tissot (1896-1902).

Overview: The Sunday lectionary for August continues what began on the 17th Sunday in Ordinary Time, namely, a brief departure from the Gospel of Mark. The focus shifts to the sixth chapter of St. John’s Gospel, beginning with the multiplication of the loaves. From the 18th-21st Sundays, we meditate on the Bread of Life discourse of the Fourth Gospel, divided into four sections. The first two emphasize the importance of faith for salvation. The second two emphasize the necessity of eating and drinking the Body and Blood of Christ. The readings for the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary form the basis of proper devotion to the Blessed Mother. Finally, for the 22nd Sunday of Ordinary Time, the lectionary returns to St. Mark’s Gospel, with the theme of true obedience to the Law of God.

________________

Eighteenth Sunday of the Year-“B”— August 2, 2015

Purpose: Faith is more than assent to an intellectual proposition; it is finding God at the heart of things, a discovery that attains its end by loving and trusting Christ.

Readings: Exodus 16:2-4, 12-15; Psalm 78; Ephesians: 4:17, 20-24; John 6:24-35

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/080215.cfm

What do Pope Francis and an entire generation of chefs, bakers, and “foodies” have in common? A favorite film, Gabriel Axel’s “Babette’s Feast” (1987), based on a novel by Isak Dinesen. Set in a 19th-century Danish fishing village, the story, filled with Biblical/religious imagery, depicts the life of a small Protestant sect founded by a venerable Lutheran pastor, and cared for after his death by his pious daughters Martine (Luther?) and Phillipa (Melancthon?). Into this world of earnest, severe human beings, enter two exotic visitors from Paris. These include opera singer Achilles Papin and, years later, a chef named Babette, who comes seeking refuge from the civil unrest that claimed her family. In appreciation for their kindness to her, Babette begs her hosts for the privilege of cooking a traditional French dinner for the community. Her offer is met with the same suspicion that had previously greeted Papin’s musical artistry. After all, overindulgence of the senses can lead to sin: a love song is just one step away from immorality, and sumptuous dining, from gluttony and drunkenness. Almost despite themselves, the devout believers and their guests—twelve in all—relent, and find their lives transformed by the meal. The piece de resistance of the dinner is Babette’s signature dish: cailles en sarcophage (“quail in sarcophagus”), a small partridge-like bird baked in pastry. The effect of the food and wine goes beyond their merely aesthetic properties. A sensuous experience acts as the medium through which ineffable beauty—whose source is God—draws the human heart to itself. Indeed, according to one guest (a cultivated military officer), Babette’s meal brings about “a kind of love affair between heaven and earth.” So, too, among the guests: frayed relationships are healed, isolation gives way to tender affection, and the love of God binds together the hearts of all. In the words of the scriptures, “Taste and see the goodness of the Lord” (Ps. 34:8).

This beautiful film, much like today’s scriptures, embodies what theologian David Tracy calls the “analogical imagination” underlying the Catholic sacramental system. According to this idea, the material world has the capacity to convey the grace of God. Of course, the Bible does not argue this point by making technical, metaphysical distinctions. Instead, it uses concrete realities–people, places, and things—to show that God becomes tangibly present to believers, giving them life in this world, and in the next. With this in mind, we turn to today’s Scriptures.

The first reading from the book of Exodus describes the people of Israel engaging in typical human behavior. Having witnessed firsthand the power of God who freed them from soul-crushing slavery in Egypt, they fail to trust him when it comes to more mundane matters. As once they complained to God and Moses about Pharaoh’s unreasonable demands during their slavery, so now they are overcome by fear of the journey in the desert and, subsequently, thirst, hunger, the quality of food, etc. In short, the people fail to trust that God is concerned with their physical well-being, to say nothing of their loftier aspirations. St. Ambrose (On the Mysteries, #44-48), points out that in sending food from heaven—quail (flesh) and manna (bread)—God attends to the basic needs of his children, while at the same time foreshadowing a food that would nourish them for eternal life. Today, Christians interpret this “heavenly bread,” or “food of angels,” of which the psalmist sings (Ps. 78:25), as the sacrament of the Eucharist.

The first reading, especially its theme of trust in divine providence, is the context for today’s Gospel. Following last Sunday’s account of the miraculous feeding of the crowds, the following Sundays concern its deeper meaning: this week and next, the importance of faith in Christ, and the next two, what Catholics call the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist.

St. Augustine comments that, just as he had satisfied them with bread, so now Jesus desires to feed the people with his word. In order for this to happen, he tries to awaken in them a genuine hunger for eternal life, not simply the prolongation of earthly existence. Yet, as is typical of the dialogues in the Fourth Gospel, Jesus and those with whom he converses are speaking on different levels. For example, the Samaritan woman earlier speaks of “water” in an earthly sense as what sustains physical life, while Jesus speaks of “living water,” or faith, which is necessary for salvation. Just so, the people today are drawn to Jesus, not because the “sign” of the loaves arouses their faith in the one on whom God has set his “seal” (or what St. Hilary calls God’s “perfect impression”), but by the prospect of another meal, after which they would again hunger.

Thus, Jesus directs the people to “work for … the food which endures for eternal life,” and not settle for lesser things. Work, in this sense, is not the kind of labor associated with tilling the soil, gathering grain, or baking loaves, but of “believing in the Son of Man.” Augustine observes the enormous difference between merely “believing” Jesus, that is, intellectually grasping what he says, and “believing in” him, i.e., trusting, honoring, and loving him. Surely, a devil can do the former, but only the disciple is capable of the latter. For Augustine, to be so caught up in earthly, passing things that one fails to appreciate—and respond to—the inner realities they convey, is to make a tragic blunder.

In the weeks ahead, the Church asks us to meditate on the sacramental presence of Christ in the Eucharist, which is neither a merely physical reality, nor purely a symbol. The creative tension between the interior act of “believing in” Jesus, and the concrete act of “eating” his body and “drinking” his blood, will come to the fore. Interestingly, the pastry “sarcophagus” from “Babette’s Feast” is a powerful Eucharistic reference, inasmuch as the word is based on two terms we will hear in the weeks ahead (sarx=flesh, phagein=eat). May all Christians, who trust in Christ as they eat his flesh, make their own the prayer after Communion: “Accompany with constant protection, O Lord, those you renew with these heavenly gifts and, in your never-failing care for them, make them worthy of eternal redemption. Through Christ our Lord.”

_________________

Nineteenth Sunday of the Year-“B”—August 9, 2015

Purpose: Jesus alone satisfies the soul’s deepest “hunger”: the longing for eternal life.

Readings: 1 Kings 19:4-8; Psalm 34; Ephesians 4:30-5:2; John 6:41-51

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/080215.cfm

Few experiences of suffering are more universal and immediate than hunger. In a poignant scene from the Odyssey, Homer’s wily wanderer finds himself stranded on the shores a paradise so remote from the rest of civilization that its inhabitants believe they are more likely to be visited by the gods than by ordinary people. Indeed, Odysseus’ mysterious appearance before the royal court has all the earmarks of divinity. So to convince them that he, too, is mortal, and also garner assistance from the virtuous King Alcinous and Queen Arete, he summons the memory of an aching so deep as to bring both prince and pauper to their knees:

However the noble, suffering mind, may grieve

Its load of anguish, and disdain to live

Necessity demands our daily bread,

Hunger is insolent, and will be fed.

(Homer, Odyssey, bk. 7, line 300, trans. Alexander Pope)

Of course, the obvious meaning of “hunger” here is the desire for food but, for human beings, hunger also evokes more profound longings than a next meal: to be who they are meant to be, to attain the end for which they are born, to find their way home. Even in our own time, the Bard of the working class—Bruce Springsteen—sings: “Everybody’s got a hungry heart…”

On the 19th Sunday of the Year, the Church asks the disciples of Christ to consider that for which we truly hunger. Of course, in an age of plentiful resources and advanced technology, the extent of literal hunger afflicting the human family is nothing short of a scandal, and demands a generous, Christian response. Yet, even if hunger were eliminated once and for all, the question of our mortality remains. Food, medicine, friendship, education, and culture may temporarily put off, but never eradicate, the nagging realization that we will one day leave this mortal coil. What, if anything, lies beyond the vale of tears? And what impact does this conviction have on the way we live here and now? With these questions in mind, we listen to today’s Scriptures.

In a sense, the first reading from the Book of Kings points us in two directions: the past and the future. Like Odysseus, Elijah the prophet is on the run from powerful enemies, in this case, the wicked Queen Jezebel. He incurs her wrath after performing a miracle that undermines her court prophets—and leads to their doom. He therefore flees into the desert toward Mount Horeb to find refuge, and to renew Israel’s covenant with God. Horeb is another name for Sinai, and it is significant that Elijah travels forty days and nights to arrive there; the Lord even provides him with food that miraculously appears in order to strengthen him for the journey. All of these elements suggest that Elijah “recapitulates”—or repeats—in himself the experience of God’s people who received the Law on the mountain, wandered the desert for forty years, and were fed with manna from heaven. While his famished condition is satisfied by a hearth-cake and a jug of water, Elijah really hungers for something greater—the covenant with God—and goes in desperate search for it. The sacred author suggests that even if human beings are unfaithful, God will remain faithful, and he will vindicate and protect his servant against seemingly insurmountable odds. For Christians, the story also points to a future event, namely, Jesus’ gift of the Eucharist, the heavenly food that is his Body and Blood. The story of Elijah highlights a feature of the Catholic view of the Eucharist, namely, that it is food for our earthly pilgrimage toward heaven. Indeed, the term viaticum—the Eucharist for those who are near death—means “food for the journey.”

Today’s Gospel, in turn, hearkens back to the travails of God’s people in the desert, even to the detail that they “murmur” about Jesus just as they had Moses. We should, perhaps, not be too quick to condemn those who came to Jesus for food. In contrast to the peckish mood in which people today often find themselves around lunchtime, the specter of starvation was constant and cruel for the people of the ancient world. Jesus, of course, is compassionate to them in light of this threat, and so feeds them. Yet, he also tries to elicit from them a nobler, holier kind of hunger. According to St. John Chrysostom, Jesus tells them: “I fed your bodies, that you might seek the more diligently for that food, which is not temporary, but contains eternal life.”

The message today—that Jesus himself is the Bread of Life come down from heaven, giving eternal life to those who believe—is simply too much for the crowd to accept. After all, the people are pretty sure they have Jesus all figured out; they know exactly where he came from, and it certainly was not heaven! The people’s reaction is another example of Johannine irony; they think they know Jesus’ ancestry, but there is much more to the story, specifically, his divine origin. This is why Jesus answers that no one comes to him unless “drawn” by the Father through the gift of faith. Likewise in the creed, we recognize that Jesus was born a human being, for this is historical fact, but we also acknowledge in faith that he is “God from God, light from light, true God from true God.” Such faith is not merely an intellectual proposition; it is an act of the will, in which we commit ourselves, body, soul, mind, and spirit, to the person of Christ, and thus attain eternal life.

This, of course, brings us to the moral and spiritual demands of the gospel. St. Augustine reminds us that it is not enough simply to eat and drink of the flesh and blood of Christ, for to do so unworthily is (according to St. Paul) to heap condemnation upon ourselves. Worthy reception of the Eucharist demands a pure mind and forgiving heart, ensuring that we not only receive the Body of Christ, but are, in fact, the Body of Christ as well.

The Scriptures today encourage us to stand in awe before the mystery of the Eucharist, to be seized by the love of Christ, and to live as his faithful disciples. No matter what plans we make, or feats we accomplish, such things will come to an end. Yet, by receiving the Body and Blood of Christ, we have access to the life that will not pass away, and find purpose and direction in all we do here below.

____________

Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary—August 15, 2015

Purpose: Devotion to the Assumption of Mary is a celebration of the grace of Christ, the responsibility of disciples to act on God’s word, and the heavenly glory to which we are called.

Readings: 1 Chronicles 15:3-4, 15-16, 16:1-2; Psalm 132; 1 Corinthians 15:54-57; Luke 11:27-28

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/081515-day.cfm

Catholics often notice the eyes of their Protestant friends glaze over when explaining distinctive aspects of the faith, specifically, our devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Even with careful explanation, three main objections arise: that there is no Scriptural basis for devotion to Mary, that she has an unfair advantage over the rest of us, and, yes, that we Catholics “worship” Mary.

The Marian dogmas, one of which we celebrate today, are a case in point. In the 1950 Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus (“Most Bountiful God”), Pope Pius XII defines that “the Immaculate Mother of God … having completed the course of her earthly life, was assumed body and soul into heavenly glory.” Our friends want to know in plain English what this means. Thus, it is helpful to consider the Biblical basis for our devotion, Mary’s unique connection with Jesus, and the practical and spiritual relevance of the Marian doctrines.

While there is no account of the Assumption in the New Testament, there is much Scriptural support for her exalted role in salvation history. The first reading from the Book of Revelation refers to a glorious woman “clothed with the sun” giving birth to a male child, who is “caught up to God and his throne.” In turn, God prepares a special place for the woman. Clearly, the child refers to Jesus; the implication, then, would be that the woman is his mother Mary. Yet, there is a compelling case that the woman symbolizes the Church, as the language reflects the dream of Joseph (Gen. 37:9-10), before whom the sun, moon, and stars (his father, mother, and brothers) would bow. Jesus, in this light, would be the ruler of the New Israel. So then, who is the woman? Mary? Israel? The Church? For Catholics, the figure is “multivalent,” and can legitimately refer to all three. Yet, Mary never stands in isolation, either from Jesus, or the rest of us, because the narrative both anticipates the divine Messiah, and witnesses to his victory over death.

Likewise, in the second reading, St. Paul tells the Corinthians that Christ is the “first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.” Just as through Adam’s sin all died, so, too, all who belong to Christ, the New Adam, will enjoy eternal life in him. Among these, it follows that his mother, who was his first and greatest disciple, would occupy a pre-eminent place among redeemed humanity.

The Church places today’s gospel alongside a later allusion to Mary (again from Luke) in the gospel for the Vigil Mass. Jesus responds to a woman in the crowd who cries out that his mother is blessed because she bore and suckled him. He replies, “Rather, blessed are those who hear the word of God and observe it.” St. John Chrysostom asks whether Jesus here shows any disrespect to his mother. He answers that this is not the case; our Lord simply shows “that his birth would have profited (Mary) nothing, had she not been really fruitful in works and faith.” In short, Mary is like all believers in her faith and good works, but she surpasses the rest of us in her faithful discipleship.

Today’s gospel recounts the Visitation. A constant theme in Luke’s Gospel suggests that, in the Kingdom of God, there will be a reversal of the way things are here below. God shows mercy to the humble, raises up the lowly, and feeds the hungry, while he scatters the proud, casts down the mighty, and sends the rich away empty. Luke’s account of the beatitudes contrasts the rewards that await the poor, with the woes reserved for the rich; even on the cross, he promises paradise to the repentant thief (Lk. 23:43). Thus we appreciate the dignity of Mary who identifies, not with the mighty, but with the humble. In the divine logic of the gospel, it follows that the lowliest of God’s servants experience the greatest exaltation. St. Ambrose even connects a minor detail with the idea of the Assumption, namely, that “Mary…traveled to the hill country in haste.” He writes: “For what could Mary now, filled with God, do but ascend into the higher parts (heaven) with haste!”

We turn, then, to the Dogma of the Assumption, a truth that only God can reveal. Pope Pius XII states that Mary, by a unique grace, “completely overcame sin … and as a result … was not subject to … corruption of the grave, and … did not have to wait until the end of time for the redemption of her body (MD #5).” Is this “unique privilege” a delusional overestimation of Mary’s importance? Not at all. Cardinal Newman states that Catholics think of Mary as “a mere child of Adam,” while Pope Pius points out that Mary, like all human beings, died a real death (MD #14). Nevertheless, the dogma emphasizes the power of Christ with respect to Mary’s unrepeatable role. Grace prepares her to be the worthy vessel of the Word, and makes her, in the words of today’s Eucharistic Preface, “the beginning and image of your Church’s coming to perfection” in heaven. The lesson of the Assumption is that the Blessed Mother attains what all believers hope one day to share. Moreover, Newman claims that proper veneration of Mary in Catholic piety enhances our belief in the divinity of Christ, whereas the traditions that fail to honor Mary tend, paradoxically, to diminish Jesus as a merely excellent human being, but little more.

There are two kinds of benefits that accrue to celebrating the dogma of the Assumption: the ethical and the mystical. Regarding the former, we consider that Pope Pius was writing for a world reeling from the aftermath of two world wars, with genocide and destruction on an unprecedented scale. Materialistic ideological movements (Communism, Marxism) rejected the dignity of human beings. Catholicism, by contrast, does not treat human beings as means to an end. It emphasizes the value of, and care for, human life—both individually and collectively—by beholding persons in the light of eternity. The Pope writes: “… while the illusory teachings of materialism and the corruption of morals … threaten to … ruin the lives of men by exciting discord among them, in this magnificent way (the Assumption) all may see clearly to what a lofty goal our bodies and souls are destined.” (MD, #42) Even today, we find ourselves in an age of martyrdom, genocide, and technologies that sacrifice human life for utilitarian goals. The Assumption of Our Lady reminds us that human beings are of inestimable, eternal value.

Likewise, there is nothing strange about the religious benefit of Marian devotion. Honoring others is an eminently human enterprise, and expresses our deepest hopes and values. The only question is: what exactly do we honor? In a culture of celebrity, individuals are famous for their good looks, wealth, power, or, in a perverse way, simply being famous. Consequently, the Blessed Mother, who lived and died in almost total obscurity, is the ultimate “anti-celebrity.” The opposite of “it’s-all-about-me” narcissism, Mary deflects attention away from herself, preferring instead that her “soul magnify the Lord.” She dedicates her entire being to God, and because her fidelity is so pure, it is staggeringly fruitful. Literally fruitful, in that she gives birth in the flesh to the Savior of mankind; figuratively fruitful, in her example of contemplative discipleship (Lk. 2:33, 51), trust in the midst of danger (Mt. 2:21) and confusion (Lk. 1:34,38; 2:48-50), solidarity with those in need (Jn. 2:3), and motherly care (Jn. 19:26). By desiring God so completely, unobstructed by sin and selfishness, she attains what she desires: communion with God in heaven. Surely, our Christian brothers and sisters can appreciate that, by honoring Mary, we obey the Lord’s word that whoever receives a holy person “will receive the same reward” (Mt 10:41).

_______________

Twentieth Sunday of the Year-“B”—August 16, 2015

Purpose: Christians acknowledge the Eucharist as the sacramental presence of Christ, in which they experience the transforming power of his sacrificial death and resurrection.

Readings: Proverbs 9: 1-6; Psalm 34; Ephesians 5:15-20; John 6:51-58

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/081615.cfm

In “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” Oscar Wilde writes tongue-in-cheek that “the only way to get rid of temptation—is to yield to it.” This may be true, but to yield is to surrender in the struggle for a holy, happy, and peaceful life. (It is worth noting that the controversial Wilde died a Catholic, having found in the Church the mercy he so longed for after a lifetime of questionable choices.) One of the most important ways Catholic Christians show their love for God is to establish good habits in our moral and spiritual lives. By “habit,” we mean a stable, predictable pattern of human action directed at the attainment of virtue (or, tragically, vice). There are, of course, many kinds of virtues, i.e., “strengths” or “excellences.” Some are natural, in the sense that reason, without respect to faith, guides action; it follows that people of various cultures and traditions can attain them. Other virtues are supernatural, strictly speaking, because they are freely given by almighty God. One can be receptive to, and cooperate with, grace, but one cannot, strictly speaking, force or demand it. Not only are natural and supernatural virtues different in terms of their origin, but in their respective goals as well. For instance, the habit of physical exercise has a natural, earthly end: good health. Supernatural habits, such as the life of prayer and the sacraments, have a supernatural goal: union with God. The subject of habit is the context for this week’s liturgy, particularly the meaning of the Eucharist, and the benefits that accrue to the sacramental life.

The Book of Proverbs is one of the “Wisdom” books of the Old Testament. The aim of these poems, ascribed to King Solomon, is to teach people about their duty to God, neighbor, and family. Today’s first reading comes from a section in which two matronly figures, identified as Wisdom and Folly, invite people to their respective banquets. Folly entices her guests with the promise of empty pleasure. Delight of this sort is fleeting and unsatisfying, and ultimately leads to doom. Wisdom, by contrast, promises true life, and satisfies a deeper desire for friendship with God.

In today’s Gospel, the evangelist likewise suggests a habitual “diet” of spiritual food leading to eternal life. Jesus’ directive to eat his body and drink his blood has been variously interpreted throughout the history of the Church. If taken literally, the passage smacks of cannibalism, which is clearly incompatible with the values of the Kingdom of Heaven. If interpreted purely as a metaphor, then the Body and Blood of Christ are no more than a mere symbol that has no real existence or power

A consideration of the text is therefore helpful, for it supports the Catholic idea of sacrament, i.e., a material reality that communicates grace. The Greek word for eating (phagein) is quite vivid, and has the force of “chewing on”; later, the Lord says that his flesh is “real food,” and his blood “real drink.” Notice too that, unlike the Synoptic gospels, in which Jesus tells us to eat his “body,” the Fourth Gospel favors the word “flesh.” The Greek word sarx, or flesh, better reflects the Semitic idea of a person’s physical composition than does the Greek word soma, or body. Moreover, the word “flesh” reminds us of the prologue of John’s Gospel, where we read that “the Word became flesh.” John’s language indicates that one consumes the entire person of Jesus in the eucharistic elements. He makes it clear that the Eucharist is neither a form of cannibalism, nor a matter of semantics. Instead, the presence of Christ is articulated in very realistic, sacramental terms.

Furthermore, while Catholics understand the Eucharist as sacred food, we must not forget its sacrificial dimension. Whenever we receive Holy Communion, we participate in the once-and-for-all sacrifice of Jesus, who died on the cross for our salvation. Thus, while the Eucharist is a meal, it is also a sacrifice: the power of Jesus’ death and resurrection becomes real and effective in our lives today.

Consequently, the reason we make it a habit to receive the Eucharist is so that we may progress in our spiritual lives. Catholics traditionally speak of the “fruits” of the Mass, or what we might also call “habits” of holiness. The new Catechism of the Church mentions a number of these fruits. First and foremost is union with Christ. As Jesus today states, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.” This connection to the Lord has many wonderful effects. It cleanses us from sin and gives us strength to avoid it in the future; it unites us to our brothers and sisters in the faith, and is the basis for our mutual forgiveness; it intensifies the bonds of charity and strengthens our commitment to the poor; finally, it gives us direction and hope, that our lives here on earth may lead one day to the fullness of God’s Kingdom, where there will be only life, peace, and joy.

Priests often hear the argument that the guiltier people feel because of their sins, the more hypocritical they think they are in going to the sacraments. Therefore, they stay away from penance and the Eucharist, and so deprive themselves of the strength to avoid sin in the future. Thus begins the vicious cycle of bad habits, or sin. We should not give in to such temptation, but avail ourselves constantly of the grace of God in the sacramental life, becoming one with Christ and one with each other. As St. Augustine once wrote, “If you are the body and members of Christ, then it is your sacrament (“mystery”) that is placed on the table of the Lord. When you hear ‘the Body of Christ,’ you say Amen. Be then a member of the Body of Christ that your Amen may be true.”

________________

Twenty-First Sunday of the Year-“B”—August 23, 2015

Purpose: The life of faith is a surrender to the mysterious presence of Christ and the challenge of sacramental love.

Readings: Joshua 24:1-2a, 15-17, 18b; Psalm 34; Ephesians 5:21-32; John 6:60-69

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/082315.cfm

We live, it would appear, in an age of “spin doctors”: media specialists who make it their business to present their clients in the best possible light. If a controversial remark is uttered by a politician, an entertainer, or some other celebrity, the spin doctor is there to “provide context,” to smooth out its rougher edges, to make it more palatable to the public. In the end, every word, every deed, becomes sanitized, acceptable and, sadly, bland. How refreshing, then, when someone says, “Yes, I said/did it, and I meant it,” or, by contrast, “Yes, I said/did it, and I was wrong. Forgive me.” We have a certain respect for people who take responsibility for their words and actions.

In today’s Scripture readings, the servants of God are challenged in plain, simple language, without spin or qualification. They are presented with a choice, one that seems, according to conventional wisdom, to be foolish, backward, and even scandalous. Still, these people do not act within a vacuum. Their decision to do the right thing, however difficult, flows from a prior experience of love and grace that, far from making their actions a hardship, actually makes them a joy.

The first reading from the book of Joshua, depicts what you might call the “last will and testament” of the successor to Moses, who actually led God’s people into the Promised Land. It was typical of great Old Testament figures to speak to their families just before they died, admonishing them to follow the Lord. Joshua does this, not simply by ordering his people to do as they are told, but rather by reminding them of God’s love. True, it would be easy to establish agreements with the political powers of the time. The other nations were influential, and had gods made of gold, silver, and stone, something tangible one can touch and handle. Not so the God of Israel. Their trust in the Lord is rooted in the mighty acts he performed, saving them from the grip of slavery at the hands of Pharaoh in Egypt, and protecting them against famine and enemies throughout their sojourn in the wilderness. It is not surprising that the people respond by saying, “Far be it from us to forsake the Lord.”

Similarly, in the gospel today the Evangelist recounts the end of Jesus’ Bread of Life discourse. When Our Lord states that people must not only believe in him but eat his body and drink his blood to find life, many of his disciples reply, “This saying is hard; who can accept it?” For weeks we have been meditating on the very realistic language of the Fourth Gospel when it comes to the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The notion of his flesh and blood as food is declared in very realistic language; little wonder, then, that the people are scandalized. Eating another man’s flesh and blood? An abomination! Notice that Jesus does not run after them, he does not qualify his earlier comments, he does not hedge by remarking, “What I meant to say was…” No. He asks people to take him, or leave him, as he is. His close disciples look at him through the eyes of love, something that grew over the course of their friendship. These are the ones who refuse to break away from him; as Peter says, “Master, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and are convinced that you are the Holy One of God.”

Once Christians are touched by the love of God, everything changes, and this brings us to the second reading from St. Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. Priests do well to help their congregations understand what, in this day and age, comes across as a most politically incorrect passage. Suffice it to say that St. Paul in many ways is a realist. In the culture of the time, husbands and fathers were the undisputed heads of households, and enjoyed absolute and unquestioned authority in all matters. Paul does something quite radical by transforming the relationship between spouses, imbuing it with the warmth of Christian love. He compares the natural institution of marriage and family life to the relationship that exists between Christ and the Church. In the latter, Christians obey and serve Christ, but only because they have already experienced firsthand the surpassing love that brought Jesus to die on the Cross for our sins. Indeed, Paul describes this nuptial relationship—husband/wife, Christ/Church—as a “great mystery” (in Latin, sacramentum). Just so, Christian family life should be such that individuals defer to each other because they have been so moved by the love of God that they can do what to others may seem foolish, or messy, or even impossible.

As we come to receive the Eucharist today, then, let us ask the Lord to remind us of the many times we have benefited from his love and grace, and so face the challenges of life with courage, trust, and strength.

________________

Twenty-Second Sunday of the Year- “B”—August 30, 2015

Point: The Scriptures urge Catholics to adopt the proper attitude toward their duties in faith, namely, gratitude to God and loving service to their neighbor.

Readings: Deuteronomy 4:1-2, 6-8; Psalm 15; James: 1:17-18, 21-22, 27; Mark 7:1-8, 14-15, 21-23

http://usccb.org/bible/readings/083015.cfm

If teaching is one of the “noble” professions, then the teaching of young children is particularly honorable, if only because the stakes are so high for human beings at such an impressionable stage of their development. Depending upon the degree of dedication, creativity, and sheer hard work the teacher demonstrates, a child will begin a life-long love affair with learning and the value of the intellectual life or, sadly, come to see these as a burden to be avoided at all costs. Engaging his class of student teachers, therefore, a professor asked them to specify the age or need group to which they would dedicate themselves for the next two years. The first student chose middle school, the next, high school mathematics, still others, special education.The last student answered: “early childhood.” This was a remarkable response, not because of her specialization, but because of her reason: “They’re five years old: how hard can it be?” Imagine the same attitude, say, in a prospective airline pilot, or brain surgeon. Over the next two years, she learned just how hard the work of a good kindergarten teacher could be. When the stakes for some work are high, then great care should be taken to prepare one for it. Responsibility for the education of children, then, should only go to those with the proper attitude and training.

In some sense, the whole of human life is a continual process of education. Plato tells us that “the beginning is always the most important part of the work.” Catholics, in turn, know they must grow in the knowledge and love of God, and in charity toward our neighbor. The first steps we make point us in a particular direction in life. In the dog days of summer, as vacations draw to a close, Catholics should reflect upon our motivation—what precedes every task we undertake—and ask God to keep it always noble and authentic.

Our first reading is from the Book of Deuteronomy (or “second law”). Although it is ascribed to Moses, scholars believe that the book’s final form came long after the people of Israel had taken possession of the Promised Land. The book is a recollection of Israel’s sojourn in the desert, after being liberated from slavery. Recalling God’s steadfast love, manifest in the Exodus, the sacred author invites his people to adopt a more genuine devotion to the Lord by carefully observing the Law. In the Bible, law was not merely a legalistic code of behavior which must be followed out of fear of punishment. Rather, it was an attempt on the part of real people to lead genuinely holy lives, out of gratitude for the favor of God, and because of the future benefits that would accrue to them. The various precepts of the Mosaic Law were concrete actions by which people took seriously their responsibility to God and neighbor. In a word, the right attitude toward the Law—not as a burden, but as evidence of wisdom and friendship with Go—makes all the difference in the world.

Similarly, the concern of the Letter of James is the moral obligation of the faithful. It is essential that all Christians allow the word of God, received at baptism, to take root in them, and to motivate and guide their activity. Faith, for the sacred author, has a necessarily practical dimension. Simply to listen to the word of God, and not let it transform our values and conduct, is to deceive ourselves. Caring for widows and orphans, however, is the way genuine disciples of Christ show their faith. Today, we can add to the list of those most vulnerable: the aged, the unborn, the mentally and emotionally challenged, victims of crime or violence, and those persons presumed to be defective, and so, undeserving of protection.

Finally, we come to the passage from the Gospel of Mark, wherein Jesus castigates his opponents, the Pharisees and the lawyers. This section was written for an audience unfamiliar with the regulations governing Jewish ritual purity. The Pharisees attempt to portray Jesus as having contempt for the Law. When we consider his reply against the whole of the NT, however, we realize that Jesus is not undermining the Mosaic Law. On the contrary, he is the fulfillment of the law, the very embodiment of divine revelation to humanity, as well as the radical human response to the will of God. What is it, then, to which Jesus objects? Some of the verses omitted in this passage shed light on the matter. Our Lord mentions a practice by which his opponents justify withholding financial support from parents, even though the Law clearly requires individuals to honor father and mother. Jesus points out the contradiction by which people, claiming to obey the Law, actually violate it. He exposes the hypocrisy of his rivals with regard to the very thing on which they pride themselves, namely, fidelity to the Law.

Today, the Church asks us to consider prayerfully our attitude toward God and neighbor in whatever task we undertake. Catholics have a responsibility to prepare a world more receptive to the Kingdom of Heaven. It seems particularly appropriate, then, to make our own the Catholic prayer that traditionally opens every classroom lesson and public gathering. It reads: “Direct our actions, we beseech Thee, O Lord, by Thy inspiration, and further them with Thy continual help, that every prayer and work of ours may begin always from Thee, and through Thee, likewise be ended. Amen.”

Recent Comments