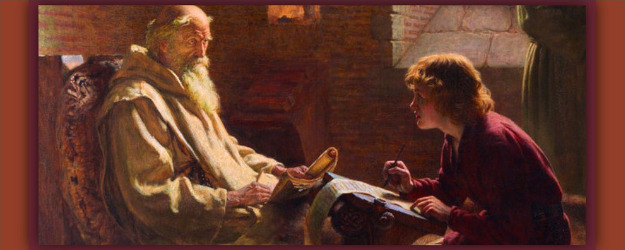

The Venerable Bede Translates John, by J.D. Penrose (ca. 1902).

Time-honored ritual; a space often ornate, if not opulent, used almost exclusively for this purpose; seating by hierarchy; candles; a prayer, perhaps in Latin, perhaps in English; ceremonial robes; a bevy of trained servers; wine; elegant, and often antique, silver and crystal; an oration, at times stilted or soporific: a recurring event all solemnly choreographed and brought to a formulaic close. By the end of the hour or two, a few may be bored, and some wonder again, “All this archaic rigmarole, so pompous and contrived and expensive, while people are starving and living in rags and hovels: would this money not be best spent on the poor?” I refer, of course, to the phenomenon known as Formal Hall.

It is an anthropological fact: Humans need ritual and ceremony. Whether a formal dinner at an Oxbridge college, a wedding, a funeral, a graduation exercise, a sporting event, an inauguration, a coronation, or people regularly gathered for worship in a church or chapel—human public life requires ritual. Likewise, human private life also has its rituals, from one’s daily morning ablutions, to how one weekly goes about cleaning the house or tidying up the garden. It is in the nature of ritual, just as it is in human nature, which never changes, to draw upon established practice and precedent, and to change slowly and with rare innovation. Within a religious context, that human instinct for ritual is called liturgy.

For that anthropological need, as well as for abiding human religiosity, one finds archaeological evidence, ranging from Neanderthal burials to the Staffordshire Hoard.1 Within the latter, seventh-century Anglo-Saxon treasures discovered in 2009, one finds a pectoral cross and what is either part of a processional cross or a cross for on top of an altar. The pectoral cross could have been worn either by a bishop or an abbot or an abbess, and the other cross, if a processional cross, would have been used during major liturgical events, carried usually by a boy from a parish or by a novice monk or nun at the front of a liturgical procession. That sort of procession was led by the most junior person present, here symbolized by a boy or a novice, and from there the church hierarchy was represented in ascending scale, so that, at the end came an abbot, an abbess, or a bishop.

To turn from archaeological finds to literary texts, one encounters just such a procession in Section 17 of Bede’s Historia abbatum, his account of the abbots of his monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow. There, the abbot, Ceolfrid (or Ceolfrith), was about to depart one last time for Rome. His departure took the form of a procession led by deacons bearing cross and candles. Once he had ridden off on his horse, the monks, despite their tears, did what monks do: they returned to the abbey church and there chanted the Psalms prescribed for that time of day.

Since it formed (and forms) the daily basis for the lives of priests, monks, and nuns, here I shall focus on that part of Christian liturgy that is called the Divine Office. Benedicta Ward has written that “the framework of Bede’s life was liturgical.”2 A monk in seventh- and eighth-century Anglo-Saxon England, Bede was neither a university professor nor an independent scholar, deciding, year after year, to write what one of Edward Gibbon’s noble patrons called “another damned thick book.” Bede had to fit his assigned tasks, his teaching and his scholarly work, what that same patron of Gibbon characterized as “always scribble, scribble, scribble,” within a liturgical timetable.3

Although Mass is offered usually once a day, Office recurs throughout the day, its regularity at certain hours of the day giving Office the other name of the Liturgy of the Hours, or more simply the Hours. This designation can cause confusion. Each Hour can, despite the name, last for five or ten minutes, or sometimes up to half an hour. So, if one hears that a priest, monk, or nun prays seven Hours a day, think not in terms of an eight-hour work day, but rather in terms of a day punctuated by seven sessions lasting only a fraction of an hour.

One can find the basic structure of Office as Bede and his confreres would have known it, outlined in Chapters 8 to 20 of the Rule of St. Benedict, written in the early sixth century between Rome and Naples. It is clear from allusions and other references by Bede that the predominant monastic rule followed at Wearmouth-Jarrow was that of St. Benedict.

Benedict based his monastic Rule on several earlier rules and ultimately on the Bible. He drew also upon liturgical customs of various dioceses, such as Rome and Milan. In Chapter 13 of his Rule, Benedict wrote that canticles from the Hebrew prophets were to be used at Office, “according to the practice of the Roman Church”; in Chapters 9, 12, and 17, he stipulated that certain Offices were to include an Ambrosian hymn, meaning one of the hymns composed in the late fourth century by St. Ambrose, bishop of Milan.

In Chapter 16, Benedict cited Psalm 119 to justify communal prayer of the Psalms seven times a day: “Seven times a day do I praise thee” (Ps 119:164). Taken together, Chapters 8 to 20 of the Rule of Benedict describe an elaborate rotation of all 150 Psalms, as well as readings from the Bible and Church Fathers such as Augustine, Basil, and Cassian. Benedict expected his monks to know many of those texts, especially the Psalms, by heart.

Whereas today, many of the Psalms may seem to be archaic relics of a Bronze Age agricultural society, and often downright brutal and bloodthirsty, their importance for Christians has been their historical and spiritual association with King David and with his most famous descendant, Jesus of Nazareth. As a pious Jew, Jesus would have prayed these Psalms, prayed them to God the Father. So, Christians, baptized into the body of Christ, believe that they are participating in Christ’s Incarnation and therefore in Jesus’ prayers to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as well as of David. From at least the days of Origen (d. c. 255), Christians have tended to read the Psalms allegorically, so that, for example, reference in them to the Lord’s enemies was interpreted to mean the various sins which humans find tempting them away from a life of virtue.4

The monastic choirs would have chanted all these Psalms and hymns in Latin. In Book Three of Bede’s commentary on Ezra and Nehemiah, he explained the relevance for monastic liturgy of Nehemiah, recording, “I assigned two large choirs of people giving praise” (Neh 12:31).5 For Bede, such a statement brought first to mind the two choirs of every monastic church. These choirs sit opposite one another, and they alternate their singing, one side chanting two, three, or four lines of a Psalm, then the other side chanting a few lines, and so on. Unfortunately, it is a musical exchange that tends not to come across well on compact discs of Gregorian chant.

In this context of the Liturgy of the Hours, Bede and his monastic community would have encountered much of the texts of the Bible. As the Church year unfolded, and Advent and Christmas gave way to Lent and Easter, and then the long months of time throughout the year, tempus per annum, the liturgy, whether Office or Mass, was the primary place for experiencing Scripture.

That experience was communal and physical: a group of people singing, listening, standing, kneeling, bowing. Even the sense of smell was included when the liturgy called for the use of incense. In the Liturgy of the Hours, incense occurs during special Vespers or Evening Prayer. Incense itself had biblical connotations: both in Psalm 141 and in Chapter 8 of the Book of Revelation, we read of prayers being associated with incense.

For a comprehensive history of the Divine Office, one ought to consult the works of Robert Taft and Gregory Woolfenden. Taft’s book is called The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West (Liturgical Press, 1986), and Woolfenden’s is Daily Liturgical Prayer (Ashgate, 2004).6 Here a few points bear emphasis. Each of the Hours begins with everyone making the sign of the Cross, a custom with obscure origins. By the late fourth century, St. Basil the Great, in his book, On the Holy Spirit, wrote about this practice and said that no one knew how or when it originated. It is not mentioned in the New Testament, but, apparently, it developed early in the Church’s history and was taught from generation to generation as part of the oral tradition.

As for the antiphonal chanting of two choirs, there survives evidence for it from the early second century. Pliny the Younger, writing around the year 112 to the emperor Trajan about Christians in the province of Bithynia, in northern Asia Minor, described those Christians as getting together every day before dawn to sing songs to one another (invicem), “to Christ as if he were a god.” The First Epistle of St. Peter referred to Christians in Bithynia, so if one accepts Petrine authorship of that letter and dates it to the early first century, that is, sometime after the mid-30s, and before Peter’s martyrdom around the year 65, then one can see the roots of Office going back to the years right after Jesus’ crucifixion, and, thus, the days when Christian worship emerged from Jewish worship.

Sometime in the fourth century in the West, a significant development occurred. According to John Cassian’s Institutes (2.8), monks in southern Gaul had begun using the Psalms to reiterate their belief as defined by the fourth century’s two ecumenical councils at Nicaea and Constantinople. Those ecumenical councils, held respectively in the years 325 and 381, had grappled with how best to articulate Christian belief in the Trinity. That belief holds that, within the one God, there are three divine Persons with one divine nature; yet, somehow, they are not three divinities, nor is it a case of one divinity expressing itself in three different modes.

The three Persons of the Trinity are in an eternal relationship of communication, of communion: the Father loves the Son, the Son loves the Father, the love flowing between them is the Holy Spirit. The Son is “begotten of His Father before all worlds,” as an older translation of the Nicene Creed put it, meaning that the Son is not created by God like galaxies or geese, willows or walruses.

While all analogies limp, the familial terminology of Father and Son derives from the Bible; and the Church, through centuries of discussion and debate, has determined that impersonal terms such as Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier describe particular actions associated with the three Persons, and would, thus, confine God to functions within time.

To underscore the Christian belief that the same Trinitarian God is found in the pages of what Christians call the Old and New Testaments, the monks of southern Gaul, wrote Cassian, would, during liturgical prayer, add a doxology to the end of each Psalm. Thus, during liturgical chanting of the Psalms, each Psalm got tacked onto it the words, “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit.” The monks would stand and bow at that invocation of the Trinity, and St. Benedict included that custom in Chapter 9 of his Rule. Today, during those doxologies, at some monasteries, perhaps as a concession to age and infirmity, the monks bow whilst remaining seated.

Notice, please, the continuity extending from the first century to the eighth and beyond. More so than vernacular language or material culture, liturgy provides “the common stream,” to borrow the title of Rowland Parker’s history of Cambridgeshire, flowing through, and thus connecting, Benedict’s era with Bede’s and our own.7 In this sense, liturgy is like the Papacy, which Walter Ullmann described as linking “the post-apostolic with the atomic age.”8

This continuity remains visible and is open to anthropological observation. In Cambridge, an excellent way to see and hear liturgical prayer based on the Psalms is at one of the colleges during choral Evensong. Eamon Duffy has described choral Evensong as “the greatest liturgical achievement of the Reformation, a perfect blend of noble prayer in memorable language set to glorious music.”9 Elsewhere in Cambridge, at Blackfriars, the Dominican house, one may find the Office of the Roman rite.

It would be instructive for a classicist, who found that, within his or her own town, there were still people seriously praying and sacrificing to Zeus or Apollo, to observe such a ritual at least once. That classicist would long to hear the Homeric Hymn to Demeter chanted, even badly, by people who truly believed in its message, and he or she would find it worth the effort of crossing town and sitting in the back as an observer.

Likewise, in order to get a better understanding of the daily round of medieval people like Bede, one would do well, and would exercise due diligence, to make time for such field work. One might feel as out of place as Flora Poste visiting Amos Starkadder’s Church of the Quivering Brethren, but if so, it would make escape to the nearest tea shop that much more of a relief.10

_______

The author gave a version of this paper to the graduate students of the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic of the University of Cambridge on May 26, 2014.

- See Zach Zorich, “Did Neanderthals Bury Their Dead?” Archaeology (March/April, 2014), p. 19; Caroline Alexander, “Magical Mystery Treasure,” National Geographic (November, 2011), pp. 38-60. ↩

- Benedicta Ward, The Venerable Bede, Cistercian Studies Series 169 (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1998), p. 10. ↩

- For this anecdote, see C. V. Wedgwood, Edward Gibbon (London: Longmans, 1955), p. 23. ↩

- See Robert Louis Wilken, “How to Read the Bible,” First Things 181 (March, 2008), pp. 24-27. ↩

- Bede, On Ezra and Nehemiah, trans. Scott DeGregorio, Translated Texts for Historians (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2006), p. 211. ↩

- See also Jesse D. Billett, “The Liturgy of the ‘Roman’ Office in England from the Conversion to the Conquest,” in Rome across Time and Space: Cultural Transmission and Exchange of Ideas, c. 500-1400, ed. Claudia Bolgia, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 84-110. ↩

- Rowland Parker, The Common Stream (London: Collins, 1975). ↩

- Walter Ullmann, A Short History of the Papacy in the Middle Ages (London: Methuen, 1972), p. 2. ↩

- Eamon Duffy, Walking to Emmaus (London: Burns and Oates, 2006), p. 3. ↩

- See Chapter 8 of Stella Gibbons’ novel, Cold Comfort Farm (London: Longmans, 1932). ↩

I hate to nit pick but St. Bede and St Benedict would have been familiar with the Vulgate and the Vulgate numbering of the psalms, not the Hebrew, hence it would be Psalm 118 and not Psalm 119. Part of our Latin and Western patrimony is the Vulgate psalter with its different numbering.