Vatican City, November 17, 2014

Dear Friends,

It is my distinct honor and personal pleasure to be with you at this important Colloquium on the complementarity of man and woman, and to share with this august assembly the perspective of what the Catholic Church considers as her and the whole of humanity’s treasure: namely, human love seen in the context of Creation and the intention of the Creator.

I have been asked to take this from the extraordinary contribution of St. John Paul II, recently called the “Pope of the Family” by our present Holy Father, Pope Francis. Philosopher, theologian, moralist, pastor, Karol Wojtyła first, John Paul II later, was extremely committed to articulating and transmitting an authentic Christian anthropology founded upon what he called “God’s design on marriage and family,” or consilium Dei matrimonii ac familiae.

My task in this presentation will be to speak specifically about the sacramentality of human love.

It seems that conjugal love has ceased to be good news in the eyes of some of our contemporaries, who rather identify themselves more with the Pharisees interrogating Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 19. The Pharisees asked Jesus a trick question on the Mosaic Law and concerning the repudiation of one’s wife through the bill of divorce. Jesus, instead, brought their attention to the initial order of Creation:

Haven’t you read, he replied, that at the beginning the Creator made them male and female, and said: For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh? So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate. (Mt 19:4-6)

In the beginning, according to a definite plan, God created the world and formed the human person as male and female. Interpreting this plan, through and with the creation of Adam and Eve, St. John Paul II teaches humanity to be constituted according to its sexual complementarity. But everything is done in the perspective of a divine plan; in this way, we understand that, from the beginning, we see the unity between what Jesus wants and realizes (this is the theological aspect) and that which man is in reality (the anthropological aspect).

Even if there is a need to deepen the natural dimension of marriage, the Church is called, above all, to carry out a mission that is, specifically, by nature theological, relative to the salvation of man. The mission of the Church is realized according to a modality that is sacramental, which is the most adequate way to express and transmit the truth of salvation. The sacrament of marriage actualizes, as do all the other sacraments, the baptismal immersion into the life, passion, death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ; marriage possesses all the riches and supernatural fruitfulness of a sacrament of salvation.

Marriage has a particular function that allows us to consider its proper mission: expressing in a particular way the nuptial mystery of Christ, the Bridegroom, and of the Church, his Bride. It is inherent in the nature of the communion of life and love between man and woman to signify and actualize the union of Christ and the Church. How is this possible? To understand this, we have to go back to the meaning of this primordial mystery and union between Christ and his Church (Eph 5:32). This union is likewise characterized as communion of life and love: since it treats of a divine good transmitted by Christ, it is a communication of eternal goods: communication of eternal life and eternal love.

I. Rediscovering the Sacramental Reality of Human Love

a) The Mystery

Saint Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, writes:

Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her, in order to make her holy by cleansing her with the washing of water by the word, so as to present the church to himself in splendor, without a spot or wrinkle or anything of the kind—yes, so that she may be holy and without blemish. In the same way, husbands should love their wives as they do their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. For no one ever hates his own body, but he nourishes and tenderly cares for it, just as Christ does for the church, because we are members of his body. “For this reason, a man will leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.” This is a great mystery, and I am applying it to Christ and the church. (Eph 5:22-33).

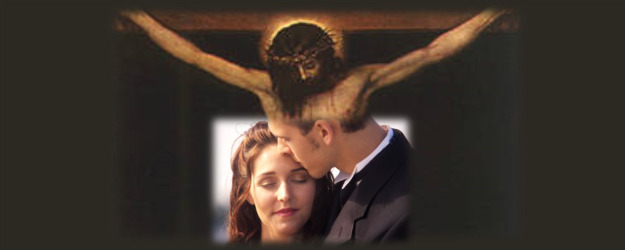

For St. Paul, human love is not understood and explained on the basis of its definition or content, but from the perspective of the divine purpose. Thus, it illuminates God’s mystery, which reveals and unfolds itself over time. The divine mystery accomplishes, realizes, and consumes itself in the love of Jesus Christ, crucified and risen. What is the connection between the original love of man and woman with Jesus’ sacrificial love? Each of these correspond with the Creator’s loving plan; but the former was wounded and bears in itself the traces of sin. Marriage, as an expression of love, not only continues having the prophetic power of proclaiming the love of God the Creator, but it also becomes a new reality, renewed by the love of Christ, who gives himself to his own, to his Church, and unites himself with her, like a husband with his wife. Marriage becomes a sacrament of the redeeming love of Christ and expresses it effectively.

St. John Paul II, in his first catechesis on human love, spoke of marriage as an expression of the Creator’s love, and, in this sense, and only in this derivative sense, called it the primordial sacrament. More frequently, in the years that followed the publication of these extraordinary teachings, he continued referring to God’s plan for marriage and the family to designate the original love between a man and a woman (consilium Dei matrimonii ac familiae). In contrast, the term mystery is used in the Pauline sense of the redemptive union between Christ and the Church.

Logically, the place of marriage within the realization of God’s love in the person of Jesus Christ, who died and rose, gives marriage a specifically ecclesial dimension: if the Church is the communication of divine love to mankind, accomplished through, and in, Christ, how could marriage express this love outside the Church? The love between man and woman is great precisely in the light of this divine mystery. Saying this doesn’t discredit the natural value of this reality, which is deeply written in the very being of man and woman. On the contrary, it implies seeing in it an implicit reference with the union of Christ and his Church.

The meaning of marriage is accomplished in Christ, though it essentially keeps its original significance. Willed by God, it is the expression of the Creator’s initial goodness:

Marriage, as a primordial sacrament, is assumed and inserted into the integral structure of the new sacramental economy, arising from redemption in the form, I would say, of a “prototype.” … all the sacraments of the new covenant find their prototype in marriage as the primordial sacrament.1

Before going into the details of what St. Paul’s text teaches about our subject, we need to take a look at the broader context into which it is placed. We know that the Letter to the Ephesians begins with a presentation of God’s eternal plan to make all people his children through Jesus Christ. Christ is placed above all things and appointed as Head of the Church, which is his body. Christ’s mystery is where God reveals himself, but it is in the Church that he makes himself known and accessible to humanity. The relationship between Christ and the Church is analogous to the rapport between the head and the body: Christ is Head of his Body, which is the Church. We have the first analogy: the head-body relationship, which is developed in the first chapters of Ephesians. This is followed by different instructions, among which, we will retain only the one that interests us here: that of loving as Christ did, proposed by the Apostle as the model: “Therefore, be imitators of God, as beloved children, and live in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:1). After this, some instructions that constitute domestic morality are given; these involve not only the relationship between the spouses—the main object of our attention—but also the relationship between the other members of the family community (chapter 6 and the following). Let us therefore retain the essential point: the example to imitate is Christ’s love, manifested by the total gift of himself, a gift that, because of our sin, has a sacrificial and redemptive form.

b) The Connection between the Body and the Sacrament

Every sacrament supposes a physical reality. It is, in fact, the sign of something; it refers to another reality. Obviously, in order to be meaningful, a sign has to be visible. This is a requirement related to the condition of the Incarnation. The reality to be signified is, in view of Ephesians, Christ’s love. Since this is a spiritual reality, it has to be signified by a visible sign.

The visible sign of Christ’s love is his dead and risen body (the fact that this body is risen indicates that it is also a sacrament of the Father’s love, because the Son offered himself in sacrifice to the Father, who had the power to deliver him from death).

This Pauline example of Christ’s love, is presented especially to spouses:

Even so husbands should love their wives as their own bodies. Since Christ did this for his own body, a man should leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one. This is a great mystery; I say this, thinking of Christ and the Church. (Eph 5:28-32)

In these passages, the word body is used with two different meanings: in the literal sense, it refers to the body of the man or the woman, a corporeal reality that allows them to unite and become one flesh, and in a analogical sense, the Church is called the Body of Christ, and this suggests the depth and intensity of the relationship of God’s Son to his people. This bond expresses the realization, in Christ, of the mystery we have already mentioned, and which fully occupies the intention of the Letter to the Ephesians.

The sexual union between man and woman is understood as a reciprocal gift that each one offers to the other; the human body is considered with its sexual differentiation: masculinity and femininity (Ephesians refers to Genesis 2:24). This fact is essential, although it does go against certain trends in our contemporary culture, which do not consider sexual complementarity as a fundamental anthropological structure. On this point, how can we not remember the talented way in which one of St. John Paul II’s Catecheses related this basic fact to the theme of the image of God:

Man becomes the image of God not so much in the moment of solitude as in the moment of communion. Right “from the beginning,” he is not only an image in which the solitude of a person who rules the world is reflected, but also, and essentially, an image of an inscrutable divine communion of persons.2

c) The Sacramental Nature of Marriage according to St. John Paul II

Paul’s analogy between the husband-wife relationship and the rapport of Christ with the Church sheds light on the divine mystery; in other words, it tells us something about the mutual love between Christ and the Church. Yet, at the same time, it teaches about the essential truth of marriage, the purpose of which is to reflect Christ’s gift to the Church and her reciprocating love. This reflection is not merely a likeness produced by simple imitation of the loving Christ; it is, rather, an indication of the presence—albeit partial—of the same mystery in the heart of conjugal love. Here, we need both Pauline analogies. We have already discussed the first one: the analogy of the Head and the Body. What does it correspond to in married life? Insofar as it emphasizes an organic bond between Christ and the Church, it has an ecclesiological meaning: the Church is the body that lives, thanks to Christ. The analogy refers to a somatic unity of the human organism. Applied to a man and a woman, the image signifies the organic union they form, the una caro (one flesh) that they constitute (Gn 2:24). The second analogy is that of the husband-wife relationship. Christ wanted to make his Bride holy by cleansing her with the water of baptism and the word of life that expresses nuptial love: the water-bath is an immediate preparation of the Bride (that is the Church) for Christ the Bridegroom. Baptism, in this sense, makes the Christian partake in Christ’s spousal love. Another verse: “the bridegroom presents the Church to himself in splendor, without spot or wrinkle … but holy and without blemish” (v. 25) symbolically indicates the moment of the wedding, that is when the bride, dressed in the wedding gown, is led to the husband. In this expression, we can also see an eschatological dimension: the end of time, the Bride will be eternally united with her Bridegroom, and she will be without spot or wrinkle, but instead holy and without blemish.

d) Mystery and Sacrament

“This is a great mystery, and I mean in reference to Christ and the Church” (Eph 5:32). The marriage of Christ and the Church takes place on the Cross, where the fruitfulness of the Holy Spirit is given. If the sacrament intends to express the great mystery—as St. Paul says—we must admit that it cannot ever do this perfectly. The mystery always exceeds the sacrament, not because of some kind of insufficiency of the sacramental economy, but because of human limitations: the sacrament reveals the mystery, but it implies the assent of faith. However, as St. John Paul II pointed out in his catechesis, September 8, 1982, the sacrament is something more than the simple meaning or the mere proclamation of the mystery: the sacrament is also able to realize itself in man.

The sacramental union of man and woman accomplishes in each spouse the mystery of divine love, hidden for ages and revealed by Christ’s sacrifice on Cross. The Love between man and woman is inscribed in the logic of salvation that reaches beyond us, but gradually reveals itself; through the sacramental sign of marriage, this love becomes able not only to signify this salvation but also to implement all of its efficiency.

Baptism definitively introduces man and woman to the new and eternal Covenant, to the nuptial covenant of Christ and the Church. Precisely because of this indestructible insertion, the intimate communion of life and love, founded by the Creator, is elevated and brought into the spousal charity of Christ, sustained and enriched by his redeeming power. With that being said, allow me now to move to the subject of the presence of the mystery of Christ the Bridegroom in the Eucharistic gift he makes of himself to his Church.

II. Eucharistic Gift and Spousal Love

a) The Sacrificial and Spousal Dimension of the Eucharist Gift

The institution of the Eucharist responds, in St. Luke and St. John, to Jesus’ burning desire to celebrate the Passover with his disciples. Beyond the usual ritual—the banquet of the feast, in which the master of the banquet (usually the father) blesses the cup of thanksgiving and breaks the bread—the disciples share a moment of intense communion that Jesus’ words make especially significant: “This is my body given for you; this cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you” (Lk 22:19-20). These words anticipate Jesus’ free gift of himself, Divine love, which inspires the nature of a sacrifice. The Last Supper leads Jesus into his Passion: “Jesus did not simply state,” wrote St. John Paul II, “that what he was giving them to eat and drink was his body and his blood; he also expressed its sacrificial meaning and made sacramentally present his sacrifice which would soon be offered on the Cross for the salvation of all” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 12). The life offered is also signified by the gesture of offering separately the bread and the wine: the body is given first, so that the blood that flows from it, the blood that is poured out, may mean the actual gift of life. This sacrifice is an act of supreme love: “He loved them to the end” (Jn 13:1).

The body that is given and the blood that is shed not only have a symbolic value: they are offered as food and drink to the disciples who, intentionally assembled with Jesus and with each other, and are now sacramentally—that is, really—united to him. Jesus’ paschal gift on the Cross thus entrusted to his Church, constituted at that moment, and one flesh with Christ: “The Eucharistic una caro—one body—sealed in the blood of the Cross and offered to all generations in the Eucharistic celebration, thus brings the nuptial mystery of Christ and the Church to its full completion.”3 This is very concrete: being really united to Christ means partaking in his redemptive sacrifice. The disciples who receive the body and blood of Christ become co-corporeal (Eph 3:6) with him (and consanguineous, if we may say so). We understand why union of charity is the requisite for receiving, with dignity and efficiency, the body and blood of Christ: this gift of divine love is given to the entire Church, the Bride of Christ, and continuously regenerates her. The essence of the Eucharist is thus spousal: it is the gift the Bridegroom gives to his Bride and that the Bride receives with faith.

b) The Redemption of Human Love or the Purification of the Gift

The event on Calvary and Christ’s Resurrection determine the whole sacramental economy, present and transmitted in all the sacraments. Marriage is, in a special way, in St. Paul’s perspective, connected to the Mystery of Redemption, and this has made it, in this sense, a prototype, as St. John Paul II put it, of all other sacramental signs. We now understand this better: as primordial sacrament, it is the model according to which salvation is accomplished, the spousal gift received by the Church-Bride. “The original unity resides in the fact,” Balthasar writes, “that the Church was fashioned out of Christ, just as Eve was fashioned out of Adam: She flowed from the pierced side of the Lord as he slept on the Cross. She … is his body, just as Eve was the flesh of Adam’s flesh.”4

The new sacramental action is not offered to Adam and Eve before the fall, but to those who bear the weight of original sin, and in whom “the flesh desires what is opposed to the Spirit, and the Spirit desires what is opposed to the flesh” (Gal 5:17). The drama of sin prevents the donation from bearing fruit with the magnitude and the strength present in the Creator’s original plan. The gift that characterizes the covenant of the spouses needs to be continually purified: the “ethos of the gift” is an “ethos of redemption,” to use the words of the Catechesis (19; 117). Here, the word “ethos” signifies the free accomplishment by the spouses of the truth inscribed in their being.

To be precise, Redemption leads to the consolidation of all the aspects of this natural truth; thus, for example, it strengthens the indissoluble character of the covenant between the spouses, which existed when Creation began (the principle Jesus indicates to the Pharisees, but that their hard-heartedness prevented them from perceiving (Mt 19). The body of the spouses, sacramentally inscribed in the horizon of Redemption, experiences the assumption of all the original values inscribed in its nature. This excludes, for example, adultery, which not only contradicts the nature of the marital covenant, but also deprives the body of its deeper meaning (adultery will never be a gift); adultery—the fact is better understood in this light—is incompatible with the reception of the Body and Blood of Christ. But Redemption is also operating, primarily within man, purifying his heart, because it is in the heart that evil desires are born: “I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Mt 5:27–28). In an indirect interpretation of the text, St. John Paul II has extraordinarily strong words: “Jesus assigns, as a duty to every man, the dignity of every woman: and simultaneously (even though only in an indirect way), to every woman, the dignity of every human.5

The Redemption of the body establishes the spouses in the hope of the revelation of the children of God (Rom 8:19), when the love of charity, that inspired the life of the husband and the wife in the transient condition of the world, will continue. The very form of the sacrament of marriage, the words of consent exchanged by the spouses: “I take you for my wife, for my husband,” imply “precisely that perennial, unique and unrepeatable language of the body,” as noted in the Catechesis 18. The term “language of the body” points to the interpretation which man and woman can grasp as inscribed in their nature (sexual nature), which enables them to signify, in their bodies, the mutual gift of themselves, which they are offering to one another through the exercise of the sexual faculties. The redemption of the body anticipates the time of the Resurrection, because only after their resurrection will man and woman be fully given to the truth that embraces the totality of what they are (and in particular, the truth of their corporal nature). Here, as baptized, it is in Christ that spouses are given to each other.

So, the spouses take part in the sacrificial life of Christ, because the spouses publicly manifest their membership in the Church by a gift that unites them in Christ. This gift belongs to the Church. Their participation in the nuptial mystery of Christ and the Church is an objective, and permanent, fact. It is public and, therefore, visible, and, hence, the reality of their life becomes an efficacious sign of the mystery of Christ’s love for his Church.

In the post-synodal exhortation, Familiaris Consortio, St. John Paul II states:

The content of participation in Christ’s life is also specific: conjugal love involves a totality, in which all the elements of the person enter—appeal of the body and instinct, power of feeling and affectivity, aspiration of the spirit and of will. It aims at a deeply personal unity, the unity that, beyond union in one flesh, leads to forming one heart and soul.6

The configuration of the spouses to Christ, often called their consecration, is, in no way, an outward imitation or a remote analogy: it is the work of the Holy Spirit, who deeply transforms the spouses’ subjectivity and their ability to love as Christ loved us. It sanctifies their love for one another by purifying it, so that this love becomes that of Christ himself in ecclesial witness, accomplished day after day.

Indeed, the whole question of the indissolubility of Christian marriage could be formulated on the basis of what it is, in truth, called to express: love without repentance, which is Christ’s gift to all people. This fact is just as unique as the gift a man or a woman makes of himself or herself in sacramental marriage.

This address was given at the recent Humanum colloquium, “An International Interreligious Colloquium on The Complementarity of Man and Woman”, hosted at the Vatican by the Congregation of Divine Faith and co-sponsored by the Pontifical Council for the Family, the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, and the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of Christian Unity.

- Pope John Paul II, “Marriage an Integral Part of New Sacramental Economy,” General Audience of Wednesday, 20 October 1982, in: L’Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English, 25 October 1982, p. 2. ↩

- Pope John Paul II, “Man Becomes the Image of God by Communion of Persons,” General Audience of Wednesday, 14 November 1979, in: L’Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English, 19 November 1979, p. 1. ↩

- M. Ouellet, “Il sacramento del Matrimonio e il mistero nuziale di Cristo”, in: R. Bonetti, Eucharistia e Matriminio. Unico mistero nuziale. ↩

- H. U. von Balthasar, Christlicher Lebensstand (Ital.: Gli Stati di vita del Cristiano, 202-203). ↩

- Cf. Pope John Paul II, “Christ Opened Marriage to the Saving Action of God,” General Audience of 24 November 1982, in: L’Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English, 29 November 1982, p. 9. ↩

- Familiaris Consortio, no 13. ↩

Recent Comments