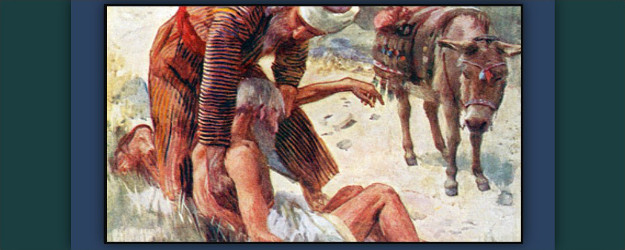

The Good Samaritan, by Harold Copping (1907).

Our faith-conviction that God is the primordial Source and Resource for all creation and human life inspires our gratitude for all as gift, and our boundless hope that the best is yet to come. The abundance of God is the ultimate Source and Resource of Christian hope in the face of death, grounding our conviction that there is more where that came from. There is an artesian well in everyone whose Source is the abundance of God. We are what we are because of who our Parent is, and once this identity becomes deeply rooted in us, then an unself-conscious giving of self will become a way of life. This is another way of saying that we “inherit the kingdom prepared for us from the foundation of the world” (Mt 25:34).

By the grace of God, we are what we are. Our worth is a gift given to us from the moment of our creation. The marvel of our life in Christ is not getting something from the outside to the inside by achieving. Instead, the marvel is coming to recognize what is already inside by the grace of creation, and learning to bring this outside by sharing and serving. It consists in seeing the first thing that ever happened to us—our birth—the way God sees it, and regarding it alongside God as something “very, very good.”

Jesus gives us this new way of perceiving the event of our beginnings—and thus of our whole lives. We, too, can begin to look on our creation the way Genesis depicts God as looking on all creation. When this begins to occur, delight rather than dissatisfaction becomes the lens through which all is perceived. What begins with a new appreciation of our own birth extends to the world itself, which means that the spirit of chronic dissatisfaction is replaced by the spirit of the One who first looked on creation and pronounced it “good.”

Every one of us has been given our chance to live by the action of Another. We did not engineer our birth into the world. It was a gift—a sheer, total, and unmerited gift. We were all given the same mandate as well: to do with our gifts and power what God does with his. God is not an irresponsible and indifferent giver. Jesus tells us that God is going to want to know at the end of our journey what we have done with all we were given in the beginning through the abundance of divine generosity. Creation is, at bottom, an act of generosity—God sharing his bounty. We have been made in the image of Generosity for Generosity. Our Creator’s magnanimity lies at the root of our being the kind of creatures that we were meant to be. Just as there is delight in our recognizing how much we have that we do not deserve or create, so there is a godly delight in seeing our generosity bless and energize others.

The parables of Jesus teach that we have to decide about what God has already decided, namely, that we are invited to share God’s joy. The joy that God sets before us can only be received; it cannot be forced on us. Jesus invites us in the following parables to share that joy.

The parables of Jesus assume that we are made in the image and likeness of a dynamic and creative God, and that we do know something of God’s ecstasy when we are in communion with God and what he is doing. It is then that we become what God had in mind for us from the beginning. It is then that we follow the example of the Holy One, described in Genesis, who freely used his power to delight himself and to bless all that he touched. This is the life that we are called to share.

The banquet image sums up what Holy Scripture reveals about the generosity, abundance, joyfulness, and exuberance of God. God does not host his banquet out of necessity or obligation; rather, God is Happiness Itself, joyfully sharing himself. The Holy One is the Generous One. God’s intention in creating was to share the joy of his goodness. There was no emptiness in God that needed to be filled. There was rather a boundless fullness that God wanted to share. God’s creative activity is not just pleasing to God or to others, but pleasing to both simultaneously. It is God’s nature to give the delight of being. It is creation’s nature to receive the delight of being.

We have been created in the image of God’s primal generosity. Loving our neighbor is making a gift of what we have been given by God. Such loving answers to the deepest impulses within us. We love because of our God-given nature to love. Others are to be loved in such a way that encourages them to become what Love Itself intends them to be.

The parables Jesus tells illuminate the meaning of our ultimate Source and Resource. His story of a midnight request (Lk 11:5-13), for example, reminds us that our lives unfold in the tension between love and fear. Love, functionally, is the perception that we are created in the image and likeness of the abundant One, and that what we already have is adequate to meet any crisis we might confront. This sense of sufficiency grounds our courage to cope or deal resourcefully with whatever occurs.

Fear, however, is the perception that there is not enough and never will be. There is not enough knowledge or love or power or time or anything else. This sense of scarcity means that we are always outmatched by overwhelming odds. Fear unmakes what is highest and best in us. We are never less loving than when we are most afraid. Fear transforms us into egocentric misfits, unable to think of anything but ourselves, and prone to all sorts of destructive behavior or indifference to the plight of others. The importance of learning to perceive reality in terms of abundance, rather than scarcity, is a question of that love which has the power to cast out fear, as the author of 1 John (4:18) affirms. We can face any and all eventualities if our sense of the Ultimate One is that of boundless abundance, generosity, and adequacy.

Jesus tells the story of a midnight request in response to the request, “Teach us to pray.” His story speaks to the issue of Ultimate Reality in a world where pagan divinities were indifferent to human plight. What happened to humans simply did not matter to the gods. In this sense, the awakened neighbor who has no sympathy for the crisis of hospitality in Jesus’ story embodies the pagan understanding of the gods.

After having expressed the unapproachable image of God in the guise of the neighbor, Jesus affirms: “But I say to you, ask, and it will be given to you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you” (Lk 11:10). The neighbor of the parable is the antithetical image of the true God. To underscore this point, Jesus describes the way a loving parent responds to a child: “Is there anyone among you who, if your child asks for a fish, will give a snake instead of a fish? … If you, then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!” (Lk 11:11-13).

The One to whom we pray, Jesus tells us, does not slumber in indifference. Rather, we pray to One who gives us more than we can ask or expect—God’s very self in his Holy Spirit—because that is God’s nature as our loving Parent. There is, then, enough, there always has been and always will be. God’s reason for creating us was to give something of himself, not to get something. There was no self-emptiness that our Creator attempted to fill by creating the world. Jesus came as the embodiment of all that our self-giving Parent ever intended human beings to be, inviting us to follow him to enjoy the abundance of Life fully.

Jesus’ story of the petulant children (Lk 7:31-35) speaks to one of the basic problems of human life: the spirit of chronic dissatisfaction. The children of the story reject out of hand whatever is proposed to them. The story reflects the unfolding of Jesus’ own life story. He had enjoyed a resounding success when he began his ministry, but as time went on, criticism of who he was and how he lived began to surface. The same people who rejected John the Baptist for being too austere, rejected Jesus for being too lax. The best that God had to offer was not enough because of the chronic dissatisfaction of the very people he had come to save. This is the spirit at the heart of sin and the opposite of what Scripture says about the nature of God.

The Genesis story tells of the One who is the wellspring of life, who decides to share that life with others. Nowhere in Genesis is there a note of dissatisfaction. God did not create out of some unhappy need in himself that he was compelled to satisfy, nor was he displeased with the outcome. God sees what God has made, and it is good because God sees it, and sees it as good. God knows, loves, and enjoys his creation, affirming that “It is very good/beautiful” (Gen 1:31).

Now clearly, something has occurred between that first moment of creation and the moment Jesus describes in his story. From whence did this radically different attitude toward reality come? Scripture suggests that it is the bitter fruit of evil entering our human experience. The petulant children represent the opposite of what God had intended. If being human had been good enough for our original forbears, the serpent’s suggestion that they become like gods would never have enticed them. Sin is a matter of trying to be either more or less than we ought to be, and either way we “fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:23). If we fail to appreciate and enjoy God’s first gift to us—the gift of one’s self—we will never appreciate all subsequent gifts.

Jesus came to save us from this condition of chronic dissatisfaction. Jesus changes the way we regard the primordial blessing of our existence. He enables us through the gift of his Holy Spirit to regard our creation the way that God regards all creation: as “very good/beautiful.” (The Greek word kalon in the creation story means both “good” and “beautiful,” with the implication that God enjoys the good that he creates.) The Spirit of God’s delight rather than dissatisfaction or indifference becomes the lens through which we see creation.

Jesus’ parable about the treasure, the pearl, and the net (Mt 13:44-50) deals with the creative changes in our lives when we discern that what is being given is really of a greater value than what is being asked for. In every change experience, we are being given something we did not have before. Even when the change has been thrust upon us, we have a choice. Even in the face of painful loss, we can count on a God who will provide something that will enhance our life if only we are open to recognize it. For those who love God as the invincible ground of their hope, there is no reason to despair. Our hope prompts us to search anew for God’s blessings.

What is meant in this parable is that each one of us, by virtue of being created, known, loved, and enjoyed by God, is the treasure buried in the field, the pearl of great price, and the fish valuable enough to keep. We are all, in God’s eyes, a treasure and pearl of great price. Christ’s redemption means being able to regard our existence the way God regards it, as something very, very good and beautiful. Seeing ourselves in the saving light of God’s love, we will know the love of self for God’s sake. We will know the joy of fulfillment in knowing, loving, and enjoying ourselves as we are known, loved, and enjoyed by our Creator in his kingdom.

Jesus’ parable of the talents (Mt 25:14-30) is a story of a God who is Generosity, enabling and calling us to become generous as his true children. Creation is an act of Generosity Itself. Jesus’ story of the talents is a call to enjoy sharing in the life of Generosity, delighting in blessing others. It assumes that we have been given our chance to live through the generous action of Another. We did not engineer our coming into existence. It was the sheer, total, and unmerited gift of Generosity. The Generosity that calls us into existence, calls us to do with our gifts what Generosity does with his. We are called to prosper in this mysterious universe by following the example or, more precisely, living in the Spirit, of Generosity, the Spirit of God freely using his power to delight himself and to bless all that he touches.

The shadow side of the parable appears in the slothful servant’s faithlessness. The servant who buried his talent was unloving, unappreciative, lazy, and ungrateful. Nothing insignificant comes from the hand of God; still, we can fail to realize the incredible significance of what has been given to us. The parable tells us that the servant’s fear and mistrust distorted and falsified the image of his master. His sense that there was not enough was all of a piece with his image of God as hard, cruel, and untrustworthy. The salvation that Jesus brings casts out this dehumanizing, false image of God. The advent of our Source in Christ Jesus reveals and communicates our unfailing Resource for our exodus from all that precludes our freedom for Joy Itself, namely, God.

Jesus’ parable of the vineyard owner and his workers (Mt 20:1-16) tells the story of day-laborers who were totally at the mercy of others for any sort of employment. Most of us, like them, have a deep aversion to this kind of powerlessness. Their condition mirrors that of each one of us in relation to life itself. In the basic structure of things, we are all beings who have been called into existence by a power other than ourselves, and we live each moment by the grace and generosity of that One who wanted us to be. None of us willed our way into this existence, nor set in motion the process that called us out of nothing into being.

We are also radically dependent by nature. We depend, like a chandelier, hanging, held in place by something other than itself. Should that something ever let go, it has no power, in and of itself, to avoid crashing down into brokenness. Such an image, however, need not depress us. The essence of Christian salvation lies in learning to trust that “Greater Than Ourselves” on whom we depend. To those who have learned to trust, however, such recognition of our radical dependence need not lead to despair. If Jesus taught us anything at all, it is that when we get to the end of our ropes, we are not at the end of everything. There is another at that point of utter extremity, and that other one is Goodness Itself. In this light, dependence ceases to be a threat and becomes a comfort.

In our story, the vineyard owner chose only a few of those assembled to go to his field. An injustice of sorts was done, for he selects only a few of the many day-laborers. Yet we hear no word of protest from the chosen ones at this juncture. They were pleased to have a whole day’s work and the promise of taking home something to their families.

This underscores the fact that our sense of justice is often highly subjective. Most of us never complain about injustice when it falls in our favor. Those who become upset at the end of the day, in our story, had no complaints when things were breaking in their favor.

As the story unfolds, when the vineyard owner returns to find other laborers still standing in the square, he tells some of them to go to his vineyard and promises to pay them an appropriate wage. At other times of the day, he does the same thing. Just one hour before the workday was to come to an end, the vineyard owner finds day-laborers who are still waiting, hoping against hope that they could get something for their families. People with less courage and tenacity would have given up long before, in despair, but here are individuals who had waited in hope for eleven interminable hours. The vineyard owner hires them, and promises to pay them what is appropriate and just.

At this point of the story, everybody is partially satisfied, for each one had received at least a portion of what he had wanted before the rising of the sun. None was going to have to go home empty-handed to a houseful of hungry children.

Trouble starts at the close of the work day when the vineyard owner instructs his steward to call in all the laborers and pay those who have worked the least amount of time first, and then pay the rest. Needless to say, the laborers who had worked just one hour were astonished and delighted to receive the going wage for a full day’s work. Those who had been hired earlier were outraged and demanded an audience with the vineyard owner. He explains to them that no injustice has been done because he has paid them exactly what he had agreed to pay them. He adds that he is free to do what he wants with his abundance.

The parable deals with issues deeper than the issues of justice and fairness. If we had earned our way into this world or had received our existence as some sort of entitlement, then there might be validity to the complaint of unfairness. But the pivotal point of this parable is grace, not entitlement, and the same is true of life as well. Birth is a windfall, and life is a gift. We were called out of nothing into being in an astonishing act of generosity for which we can claim no right. Once that gift becomes our central focus, it changes forever how we interpret things. If entitlement is our vantage point, we evaluate the particulars of our lives from that perspective. On the other hand, if grace is our starting point, everything begins to appear in a radically different light.

Divine Generosity Enables Human Generosity

Luke recounts two complementary stories of life in the Spirit. His Parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 11:29-37) tells of the priority of our giving in relation to our neighbor in need, implicitly answering the question of whether it is more important for us to give or to receive. His story of Martha and Mary (Lk 11:38-42) complements the Parable of the Good Samaritan in the response to the same question. In our relationship with God, receptivity is the only appropriate relationship.

Luke’s complementary stories affirm that we cannot give anything to others that we have not received from God; therefore, receptivity to the grace and call of God is indispensable for an authentically human or relational life in communion, community, and communications with God and all others under the sovereignty of God’s love.

Luke’s teaching method: Luke’s spiritual pedagogy employs balance and couplets. He underscores the complementarity of male and female Christian witness to God, for example, in the stories of the shepherd and the housewife in search for what was lost. The Good Samaritan and the Martha and Mary stories underscore the reciprocity of giving and receiving wherever there is authentic love of God and neighbor. We cannot give what we have not received (Martha and Mary); therefore, we should freely give what we have freely received (The Good Samaritan) with the same loving and generous spirit of the Giver of all Gifts. Our generosity bears witness to our communion, community, and communication with Generosity Itself. True sons and daughters manifest the life of their Parent.

Complementary aspects of the spiritual life appear within the Martha and Mary story. The spiritual life is a unity in reciprocity, reflecting that of the Triune God. The very word “spirit” etymologically refers to the breath of life. A “spirituality” is a way of life which, like the breath of life, implies an inhaling and an exhaling, an intake and an output. Jesus Christ, full of the Spirit of God, transforms humankind by communicating it.

In Luke’s story, Mary’s receptivity represents all who “inhale” the Holy Spirit of Christ, just as Martha’s activity represents all who “exhale” the breath of divine life that they have “inhaled” through the self-gift of God in Christ. Martha’s outgoing, loving activity of service is both the counterpart and expression of Mary’s loving welcome to God’s self-gift or Spirit of eternal love and life in Christ. The two sisters, living in one and the same Holy Spirit of Christ, represent the complementary aspects of all Christian life in the Spirit of Christ.

Aquinas’s theology of love contributes to deepening our appreciation of the deeper meaning of the life that is symbolized in the Martha and Mary relationship. The active receptivity of God’s Spirit of love ever seeks expression among those who have welcomed it. Although the receptivity and expression, “complacency and concern” (For more on this, see Frederick Crowe’s three articles on these two dimensions of love, “Complacency and Concern,” in Theological Studies 20, March, June, September, 1959), are the created effects of God’s self-gift/Spirit in us, they differ in that God works our concern (loving activity of commitment and service) in virtue of our complacency (loving welcome, appreciation, and delight). We cannot communicate the joy of God’s loving goodness if we do not enjoy it ourselves. We cannot communicate the beauty of his Word if we have not “heard” or enjoyed it ourselves. The meaning of Martha is correlative to that of Mary. We must hear or listen to the Word of God before we can speak or communicate it.

Recent Comments