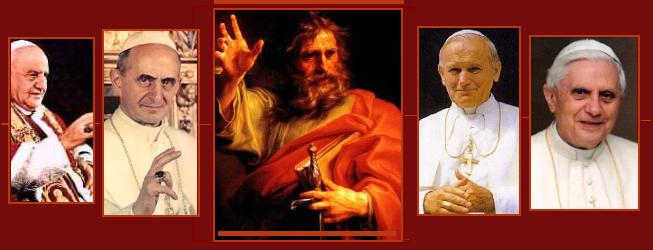

The New Evangelization is our cooperation with the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the 21st century … an evangelization foreshadowed by Vatican II, according to Popes John XXIII and Paul VI … an evangelization whose importance became more and more apparent under the pontificate of Pope John Paul II, particularly as the 21st century dawned, an evangelization Pope Benedict XVI underscored.

Popes: John XXIII, Paul VI, (St. Paul), John Paul II, and Benedict XVI

Part One

The New Evangelization is widely discussed in the Church today, even if not fully understood. We have seen erosion in the Church, especially in numbers, that has become increasingly manifest in the last 50 years despite the renewal of the Second Vatican Council. We are desirous not merely to assuage that erosion, but to rediscover the holiness and missionary zeal of the early Church. The New Evangelization is an effort to do just that in the 21st century.

Pope Paul VI saw deep-seated problems in the Church almost 40 years ago, noting “a very large number of baptized people who, for the most part, have not formally renounced their Baptism, but who are entirely indifferent to it, and not living in accordance with it.” 1 Pope Bl. John Paul II, building on Paul’s insight, noted almost 25 years ago, that there are still places where the Gospel is unknown, and places where the Gospel thrives, but also places “where entire groups of the baptized have lost a living sense of the faith, or even no longer consider themselves members of the Church, and live a life far removed from Christ and his Gospel.” 2 While John Paul underscored the Church’s mission “to proclaim Christ to all peoples,” it was for the wayward baptized that he envisioned a “New Evangelization.” 3

Pope Benedict XVI, decrying a “dictatorship of relativism” and the increasing secularization of society in the 21st century, 4 even among traditionally Christian people, has intensified the Church’s efforts to propose the Gospel anew. 5 Renewed efforts of evangelization are crucial and timely, given, as Benedict says, the challenge of “an abandonment of the faith—a phenomenon progressively more manifest in societies and cultures which for centuries seemed to be so permeated by the Gospel.” 6 Indeed, Benedict reminds us, “The Church, sure of her Lord’s fidelity, never tires of proclaiming the good news of the Gospel, and invites all Christians to discover anew the attraction of following Christ.” 7

We, Christians and Catholics, want to see the Gospel renewed in our day. We want all humanity to enjoy the same relationship with Jesus the Christ that is ours. Benedict puts it well: “As I stated in my first encyclical, Deus caritas est: ‘Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction’ (no. 1). Likewise, at the root of all evangelization lies not a human plan of expansion, but rather the desire to share the inestimable gift that God has wished to give us, making us sharers in his own life.” 8

But, what do we mean when we speak of a “New Evangelization”? Certainly, to be worthy of the name, it must be built on the foundations of Scripture and Tradition. To get a sense of the New Evangelization as proposed by the Church today, we look to some salient Scripture passages dealing with the nascent Church, and the proclamation of the Gospel, and to the Church’s Tradition as articulated in the documents of Vatican II.

As a point of departure for a discussion of the New Evangelization, let us consider a few words of Pope Paul VI, who called for “a new period of evangelization” in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii nuntiandi, appropriately know in English as On the Evangelization of Peoples. 9 Evangelii nuntiandi was promulgated in 1975, commemorating the 10th anniversary of the closing of the Council, and concluding the Third Synod of Bishops in 1974, 10 which had reflected on evangelization in the modern world. The objectives of the Council, according to Paul, “are definitively summed up in this single one: to make the Church of the 20th century ever better fitted for proclaiming the Gospel to the people of the 20th century.” 11

Paul’s understanding of the Council’s objectives is best seen as a diptych. We see the requisite holiness of the Church, that is, making herself fit to proclaim the Gospel; and, at the same time, we see her identity, not in any stasis, but in the very activity of proclaiming the Gospel. Paul’s grasp of the Council’s objectives flows from the Council’s emphasis on the holiness and mission of the Church, as in the conciliar documents, particularly Lumen gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) and Ad gentes (Decree on the Missionary Activity of the Church). Such a depiction of the people of God is rooted in Scripture. For example, as St. Peter writes, “you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Pet 2:9). In other words, there is a reciprocal relationship between the holiness of God’s people and their responsibility to proclaim God’s mighty acts. This relationship was evident in the earliest days of the Church. It is a theme that has its roots in salvation history, as God “set his heart in love” on a people he chose for himself to be a “light to the nations” (Deut 10:15 and Isa 42:6; see Isaiah 60).

For Paul, “the Church is an evangelizer, but she begins by being evangelized herself … In brief, this means that she has a constant need of being evangelized, if she wishes to retain freshness, vigor, and strength in order to proclaim the Gospel.” 12 Paul’s words were, it would seem, in the mind of John Paul II when he spoke to the Latin American Episcopal Conference just eight years after Evangelii nuntiandi, saying, “The commemoration of the half millennium of evangelization will gain its full energy if it is a commitment, not to re-evangelize but to a New Evangelization, new in its ardor, methods, and expression.” 13 Here, John Paul builds upon Paul’s words. Paul had called for “a new period of evangelization,” but John Paul coined the phrase a “New Evangelization.” John Paul would go on to use that phrase extensively, especially in Redemptoris missio. Twenty-five years after Evangelii nuntiandi, John Paul wrote, in Novo millennio ineunte, “we must rekindle in ourselves the impetus of the beginnings, and allow ourselves to be filled with the ardor of the apostolic preaching which followed Pentecost. We must revive in ourselves the burning conviction of St. Paul, who cried out: ‘Woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel’ (1 Cor 9:16).” 14

Pope Benedict, following his predecessors’ lead, also speaks of Pentecost. In declaring a Year of Faith to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Council, Benedict said, “The Church on the day of Pentecost demonstrates with utter clarity {the} public dimension of believing and proclaiming one’s faith fearlessly to every person. It is the gift of the Holy Spirit that makes us fit for mission and strengthens our witness, making it frank and courageous.” 15

The gift of the Holy Spirit looms large within the trajectories of the Acts of the Apostles and Vatican II. Immediately after the reception of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, Acts 2 finds St. Peter, standing with the Eleven, engaged in the proclamation of the Gospel. Grounding his evangelization in the words of the prophet Joel 2:28–32, Peter pronounces, “whoever calls upon the name of the Lord shall be saved” (Acts 2:21). His context is, of course, Jerusalem, and his audience Palestinian and Diaspora Jews, wherewith Peter is fulfilling Jesus’ prophecy: “You will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8b). We find that prophecy fulfilled in St. Paul, whom St. Luke tells us at the end of Acts, is at Rome, “preaching the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ quite openly and unhindered” (28:31).

St. Paul repeats the same words of Joel in Romans. The Apostle to the Gentiles struggles to portray the generosity of God in extending salvation in Christ to Gentile, as well as Jew, in Romans 9 through 11. “For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; the same Lord is Lord of all and bestows his riches on all who call upon him. For ‘everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord, will be saved’” (Rom 10:12–13). Pentecost, then, is not the reception of the Spirit as a proprietary possession of the Church, as if merely an animation of the elect. The Spirit in the Church is much more than that. The Spirit is simultaneously an animation and a dynamism. The moment of the Church’s birth in the Spirit at Pentecost is the moment of its mission, an ongoing and never ending mission of evangelization. We see this in the witness of St. John the Baptist (Luke 1:17) and in the person of the Lord Jesus himself (Luke 1:35; 4:14; Acts 10:38; Rom 1:4). Likewise, we see it in the missionary ventures of the apostles (Acts 1:8; cf. Acts 8:19) and Paul (Rom 15:19; 1 Cor 2:4), just as we find the Spirit present among God’s people (Rom 15:13; 1 Cor 5:4; Eph 3:16; 1 Thess 1:5; 2 Tim 1:7; cf. 1 Sam 11:6; Mic 3:8). Ad gentes sums up the biblical witness quite well: “The pilgrim Church is missionary by her very nature, since it is from the mission of the Son and the mission of the Holy Spirit that she draws her origin, in accordance with the decree of God the Father.” 16

It is noteworthy, though not surprising, that Pope Bl. John XXIII convoked the Council with a prayer to the Holy Spirit: “Renew your works in our day, as though in a new Pentecost.” 17 John offered that prayer in response to his conviction that society in his own day was in crisis, and in a state of spiritual poverty, for which the Council would serve as a remedy and an aid to the increase of grace and Christian progress. Pope John’s vision, and that of the earliest disciples, is substantially the same, namely, that the Church, under the inspiration of the Spirit, has a mission: evangelization.

How are we to think of evangelization? Perhaps the best summary is given to us by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith:

The term “evangelization” has a very rich meaning. In the broad sense, it sums up the Church’s entire mission: her whole life consists in accomplishing the traditio Evangelii, the proclamation and handing on of the Gospel, which is “the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes” (Rom 1:16) and which, in the final essence, is identified with Jesus Christ himself (cf. 1 Cor 1:24). Understood in this way, evangelization is aimed at all of humanity. In any case, to evangelize does not mean simply to teach a doctrine, but to proclaim Jesus Christ by one’s words and actions, that is, to make oneself an instrument of his presence and action in the world. 18

The mission of evangelization neither originated with the Council, nor has it changed therewith, 19 but the 50th anniversary of the Council, and Benedict’s emphasis on a so-called New Evangelization, do demand our attention.

The last 50 years have seen much deliberation about the hermeneutic of the Council. Pope Benedict himself has been a significant voice—as theologian, peritus, curial cardinal, and pope—in fleshing out the distinction between a so-called hermeneutic of discontinuity, and a hermeneutic of reform, vis-à-vis Vatican II. The wide range of opinions among the people of God about the aftermath of the Council notwithstanding, who among us is not moved by the historical moment of Pope John’s new Pentecost and the present moment of Pope Benedict’s New Evangelization? Who among us is not desirous “that at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Phil 2:10–11)?

Likewise noteworthy, but not surprising, is the similarity in emphasis in the words of Popes John, Paul, John Paul, and Benedict: they are the popes of Vatican II and the New Evangelization.

The New Evangelization, then, is our cooperation with the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the 21st century. It is an evangelization foreshadowed by Vatican II, according to Popes John and Paul. It is also an evangelization whose importance became more and more apparent under the pontificate of Pope John Paul, particularly as the 21st century dawned, an evangelization Pope Benedict underscored. Benedict has done so in numerous discourses; in the establishment of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, 20 whose charge it is to find avenues “to propose anew the perennial truth of Christ’s Gospel”; 21 in the announcement of Thirteenth Synod of Bishops (in October 2012) to focus on “The New Evangelization for the Transmission of the Christian Faith”; 22 and in the Year of Faith. 23

Pope Paul’s summary of the Council’s goals, that is, seeing the Church engaged in an unceasing effort to prepare herself for proclaiming the Gospel, is a summary that envisions simultaneity of ever-pullulated holiness and ever-renewed mission. Such an appreciation of the people of God is well-founded in Scripture and the Council’s documents. Let us turn now to some seminal texts for a deeper understanding of the holiness and mission of the Church vis-à-vis the New Evangelization. As John Paul reminds us in Redemptoris missio, “The universal call to holiness is closely linked with the universal call to mission. Every member of the faithful is called to holiness and mission.” 24

The Holiness of the Church

One of the four marks of the Church is holiness. The Old Testament gives ample witness to God’s election of a people, to his choosing a people for his own and making them holy. The Old Testament is replete with incidents of individual and corporate election. God often calls individuals, like Abram, but God also calls a whole people to himself from all of the nations. Election always involves holiness: holiness and election are two sides of a coin. For example, the saga of Abram’s call begun in Gen 11:26 comes to a medial summary in Gen 17:1, when God demands holiness of Abram saying, “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless.” Similarly, there is a medial summary in Exodus. God commands Moses to speak to the Hebrews and say, “You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself. Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all the peoples. Indeed, the whole earth is mine, but you shall be for me a priestly kingdom and a holy nation” (19:4–6a). 25

St. Paul speaks of the same corporate election to be borne out in holiness when he tells the Ephesians that they were chosen “in Christ before the foundation of the world to be holy and blameless before {God} in love.” Or, as Paul tells the Thessalonians, “this is the will of God, your sanctification” (1 Thess 4:3b). To consider the holiness of the Church and the New Evangelization, let us focus on 1 Thess 1:4–5 and Lumen gentium.

First Thessalonians

By any stretch of the imagination, Christianity was preached successfully in the first century. As early as 1 Thessalonians, we find Paul speaking of the Thessalonians’ faith as renowned “not only throughout Macedonia and Achaia, but in every place” (1 Thess 1:8). Paul’s claim for the Romans’ faith is a bit stronger, as their faith is “proclaimed throughout the world” (Rom 1:8; cf. 16:19). Paul also quotes Ps 19:4 in Rom 10:18 to the effect that the Gospel has gone out “to all the world” and “to the ends of the earth.” Here, of course, Paul is borrowing both imagery and bravado from the Old Testament. Isaiah speaks of a time when “the earth will be full of the knowledge of the Lord “as the waters cover the sea” (11:9; cf. Rom 15:12). And Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, the stone representing God’s activity becomes “a great mountain” and fills “the whole earth” leading to a kingdom that “shall stand forever” (Dan 2:35, 44). But Paul’s strongest claim is in Colossians, wherein he claims the Gospel is “bearing fruit and growing in the whole world” and “has been proclaimed to every creature under heaven” (1:6, 23)

In the opening lines of the earliest piece of extant Christian literature, First Thessalonians, written under the inspiration of the Spirit by one of the Church’s greatest missionaries, we find the ideal of evangelization. St. Paul writes, “For we know, brothers and sisters beloved by God, that he has chosen you, because our message of the Gospel came to you not in word only, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction; just as you know what kind of persons we proved to be among you for your sake” (1 Thess 1:4–5; cf. Eph 1:4). Here are all the essentials of evangelization: God’s love and election; the preaching of the Gospel in word, with the power of the Holy Spirit; and the personal witness, the conviction, of the preachers (Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy).

From the start, Paul reminds the Thessalonians of their election and connects it to God’s love. Paul also links love and election: “But we must always give thanks to God for you, brothers and sisters beloved by the Lord, because God chose you as the first fruits for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and through belief in the truth” (2 Thess 2:13). With this reminder, no doubt based on his preaching and witness in Thessalonica, Paul explicates the continuance and vivacity of salvation history, now extended to the church at Thessalonica. In 2 Thess 2:13, Paul uses the rare verb haireō (“I choose”), the same verb used in Deut 26:17–18 (Septuagint), when speaking of God choosing Israel and Israel choosing God. But, in 1 Thess 1:4, Paul uses the Greek noun eklogē for “election” or “chosen,” a word seldom used in the New Testament and not at all in the Septuagint. It is a word that means to be “selected,” literally “called from” (ek and legō). Paul also uses it in Romans (9:11; 11:5, 7, 28). 26 While there are other words used for election such as haireō in the New Testament, 27 eklogē is significant because of the way in which Paul uses it. In First Thessalonians, it refers to God’s election of the Thessalonians; in Romans, it refers to God’s election of Israel.

As we mentioned earlier, Paul struggles with the corporate election of Israel, and the disobedience of so many of his fellow Jews, who refuse to accept the Christ in Romans 9 through 11. God’s election is primary, according to Romans 9. It is not a question of the flesh or of works, but of God’s call, for they were called “even before they had been born or had done anything good or bad, so that God’s purpose of election might continue” (9:11). Here, Paul explains how the old covenant flows into the new covenant in Christ. To do so, Paul appeals to a theological theme running through the Old Testament, namely, that of a remnant of the elect surviving any socio-political catastrophe or religious crisis. 28 Paul says of his situation, the situation of the sub-apostolic age, “So too at the present time there is a remnant, chosen by grace” (Rom 11:5). Thus, there is a mysterious choice by God with which Paul struggled, as he worked and prayed for his fellow Jews to accept the Christ, and with which we continue to struggle in our day. Acknowledging that they are the ones “to whom God spoke first” and desiring that they “advance in love of his name and in faithfulness to his covenant,” we pray each year on Good Friday “that the people {God} first made {his} own may attain the fullness of redemption.” 29

Election, as the Old Testament and St. Paul would have it, is a manifestation of God’s love and begins with God’s initiative. As Paul says, there is evidence of that election at Thessalonica in terms of the Gospel’s arrival “in power and in the Holy Spirit” (1 Thess 1:5a). Here, Paul indicates the personal and intimate nature of the Gospel, referring to “our gospel,” as well as the reason for its success at Thessalonica. It is important that the Gospel comes through the word of the apostles, who “proved” themselves (v. 5b), no doubt through their selfless evangelical efforts (see 1 Thessalonians 2), but the real success among them can only be ascribed to the power of the Spirit. All of this flows from what Paul mentioned earlier in verse 3, where he recalls the Thessalonians’ “work of faith, and labor of love, and steadfastness of hope in our Lord Jesus Christ.” The proof of their election, the fruition of the preachers’ words and the power of the Spirit, demonstrates itself in their response and behavior.

Throughout 1 Thessalonians 2 and 3, Paul will praise their imitation of the apostles and their endurance in suffering, and note his affection for them, and his delight in Timothy’s positive report. Paul prays to the Lord for them: “And may he so strengthen your hearts in holiness that you may be blameless before our God and Father at the coming of our Lord Jesus with all his saints” (3:13). Note that in this earliest piece of Christian literature, we find that holiness (election) and salvation (unity with the saints at the second coming) are solidified in the acceptance of the Gospel and solid conviction (both of the Thessalonians and of the apostles who preached to them), wherewith Paul praises the Thessalonians as his “glory and joy” (2:20). It is in their sanctification that God’s will is fulfilled (1 Thess 4:3a).

Twenty centuries later, Lumen gentium quotes Paul directly in stating that “all in the Church … are called to holiness, according to the apostle’s saying: ‘For this is the will of God, your sanctification’ (1 Thess 4:3; cf. Eph 1:4).” 30

The Universal Call to Holiness of Vatican II

God’s will, fulfilled throughout the centuries in his Church, is well verbalized in Lumen gentium, where the council fathers speak of God’s desire “to make men holy and to save them, not as individuals without any bond or link between them, but rather to make them into a people who might acknowledge him and serve him in holiness.” 31

The universal call to holiness is not unique to Lumen gentium. For example, we find Paul urging the Ephesians to be mindful of their calling (4:4–6). Likewise, we find great saints, such as St. Francis de Sales, reminding all Christians of their call to holiness in his Introduction to the Devout Life (1619). Pope Benedict recently praised the Introduction because of its assertion that all Christians are called to perfection, which foreshadowed Vatican II’s universal call to holiness. 32 We also find the call to holiness clearly articulated by the popes, such as Pope Pius XI: “For all men of every condition, in whatever honorable walk of life they may be, can and ought to imitate that most perfect example of holiness placed before man by God, namely Christ Our Lord, and by God’s grace to arrive at the summit of perfection, as is proved by the example set us of many saints.” 33 Indeed, the universal call to holiness, according to Lumen gentium, began with God’s election of Israel and culminated in a new Israel, the Church, which “moved by the Holy Spirit may never cease to renew herself, until through the Cross she arrives at the light which knows no setting.” 34

This renewal is no denigration of the Church’s inherent holiness, of the holiness of the people of God; rather, renewal is a constant admitting of the sinfulness of some of the Church’s members (e.g., Matt 13:74–50; 18:17), while at the same time acknowledging the gates of hell shall not prevail against her (Matt 16:18). Moreover, given that Lumen gentium speaks of the Church as a “sacrament of salvation” for the entire world, 35 renewal takes different forms in different settings and times. The Church, therefore, “continues unceasingly to send heralds of the Gospel until such time as the infant churches are fully established and can themselves continue the work of evangelizing. For the Church is compelled by the Holy Spirit to do her part that God’s plan may be fully realized, whereby he has constituted Christ as the source of salvation for the whole world.” 36 Here, we note that the Church’s mission to evangelize does not end with the establishment of infant churches, but goes on as they—and we—continue the work of evangelizing.

The universal call to holiness sounds most clearly in the fifth chapter of Lumen gentium. 37 The chapter devotes itself to outlining the various states in life by which we may attain perfection (see Matt 5:48) and the behavior proper to the saints—to you and to me (Eph 5:3; Col 3:12; Gal 5:22). It also notes, as St. Paul says, that our freedom from sin and enslavement to God, yields sanctification, holiness (Rom 6:22). We are all called to holiness. “The forms and tasks of life are many but holiness is one—that sanctity which is cultivated by all who act under God’s Spirit and, obeying the Father’s voice and adoring God the Father in spirit and in truth, follow Christ, poor, humble, and cross-bearing, that they may deserve to be partakers of his glory.” 38

Once again, we see the Church’s holiness, and our own holiness, not so much as a passive state of being, but as an ongoing activity under the direction of the Spirit, in obedience to the Father, following after the Christ. Therewith, we greatly appreciate the first sentence of Ubicumque et semper: “It is the duty of the Church to proclaim always and everywhere the Gospel of Jesus Christ. He, the first and supreme evangelizer, commanded the apostles on the day of his Ascension to the Father: ‘Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you’ (Matt 28:19–20).”

The foundations for a New Evangelization, in terms of the holiness of the Church, are firmly rooted in Scripture and in Lumen gentium’s call for universal holiness, as Pope Paul’s insight in Evangelii nuntiandi suggests. When the Church renews herself in holiness—a process that is not only ongoing, but also never-ending this side of heaven—the Church becomes better fitted to proclaim the Gospel, better fitted for evangelization. From the moment of the reception of the Spirit at Pentecost, the Church has been evangelizing. To wit, the council fathers, building on Lumen gentium declare in Ad gentes, “The Church on earth is by its very nature missionary since, according to the plan of the Father, it has its origin in the mission of the Son and the Holy Spirit.” 39 In Part Two of this article, then, we shall turn to this mission of Christ’s Church, to proclaim the good news and to raise up generations of beloved and loving sons and daughters.

The New Evangelization: The Mission of the Church

Part Two

Pope Paul’s summary of the objectives of the Council resonates with a summary statement of Pope John Paul II we saw above, namely, “The universal call to holiness is closely linked with the universal call to mission. Every member of the faithful is called to holiness and mission.” 40 That mission is evangelization. In the thought of Pope Benedict, it is the raison d’être of the New Evangelization. “The Church, as a mystery of communion, is thus entirely missionary, and everyone, according to his or her proper state in life, is called to give an incisive contribution to the proclamation of Christ.” 41 Let us now turn to the Great Commission and Vatican II’s call to mission, especially in Lumen gentium and Ad gentes.

The Great Commission

The Great Commission is a dominical command. 42 Christians worth their salt take it for nothing less. For that reason, since the pouring out of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, Christians have evangelized. Christians have preached the Good News of Jesus Christ to all peoples, at all times, in all places, and will continue to do so until the end of time. We do this in obedience to Jesus. “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (Matt 28:19–20). “Go into all the world and proclaim the good news to the whole creation” (Mark 16:15). On the one hand, this mission is given immediately to the Eleven; on the other, it is a mission entrusted to the entire Church through the Eleven, to you and to me.

The Lord’s injunction in St. Mark’s Gospel is inclusive, if brief, like the rest of his Gospel. Its placement at the end of the Gospel, in the so-called longer ending, lends cogency to Jesus’ words and deeds in Mark. After his rejection in Nazareth,43 Jesus “goes about among the villages teaching; he then calls the Twelve and sends them out as missionaries whose efforts are recounted in Mark 6:7–8:2. 44 Mark recalls a number of salient events in the life of the Lord and his disciples, not the least of which is the healing of the Syrophoenician woman’s daughter (7:24–30). This event is preceded by Jesus’ renunciation of traditional Jewish dietary laws: “whatever goes into a man cannot defile him” (6:18). Jesus’ initial reaction to the woman’s request for help seems harsh; his analogy between the Greeks and dogs, and the Israelites and children, is especially unpalatable. But, with her recognition of Jesus as Lord, and her insistence that the “dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs” (7:28), Jesus is swayed. The Lord heals her daughter.

The reader is given to understand that salvation is extended to the Gentiles, even if they come in after the Jews, their elder brothers and sisters. This theme is not only consistent with Paul’s understanding of dietary laws, as well as Luke’s, vis-à-vis the Gentiles, 45 but also with Mark’s orientation to a Gentile audience rather than a Jewish one. 46 It is a theme that has its roots in the Old Testament stories of Elijah (1 Kgs 17:8–24) and Elisha (2 Kgs 4:18–37). So too, we find a climatic confession of faith by the centurion at the foot of the Cross in Mark: “Truly this man was the Son of God” (15:39; cf. 1:1; 3:1); meanwhile, the Eleven had deserted the Lord. Their desertion in no way mitigates their apostolic status. Instead, it provides an opportunity for the Gentiles to step forward and acknowledge the Messiah of Israel as the Christ of all men and women. We may look to St. Paul’s words to explain the mission enjoined on the Eleven—and all of us—at the end of Mark. The Gospel “is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (Rom 1:16).

The path from exclusivism to universalism is more prominent in Matthew’s Gospel. Matthew has two commissions. First, there is the calling and sending of the Twelve, with the stipulation that they “go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10:1–6). This initial commission to Israel will be expanded by the Great Commission “to all nations” in Matt 28:19. Partial inclusion develops into full inclusion as we move through the Gospel in like manner to Mark (see Acts 1:8) whilst God’s plan of salvation unfolds.

In Matt 15:21–28, paralleling Mark 7:24–30, Jesus’ encounter with the woman (here, Canaanite rather than Syrophoenician) is more expansive. Jesus states his mission clearly—at least, to his disciples—“I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (v. 24). But, given the woman’s understanding of Jesus’ identity as “Lord” and “Son of David” (vv. 22, 25, 27), her petitioning (vv. 22, 27), and her “great faith” (v. 28), Jesus extends his healing power. It comes as no wonder, consequently, to find the Great Commission in Matt 28:16–20. At the very end of the Gospel, in only four verses, we see not only Jesus’ promised appearance to the somewhat hesitant Eleven in Galilee, and his promise to stay with them, but also the renewal of the extension of his authority to them (vv. 16–18, 20b). Similarly, we find the mandate: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you” (vv. 19–20a). Again, we see Israel’s precedence in salvation history; nonetheless, we see exclusivism growing into universalism. There is but one way of salvation for Jew and Gentile: the Christ. “For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek; the same Lord is Lord of all and is generous to all who call on him” (Rom 10:12; cf. Gal 3:28; and Col 3:11).

The Great Commission, then, extends the Church’s mission field, and consequently its evangelization efforts, far afield. With the power of the Spirit received at Pentecost, the disciples will be Jesus’ “witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth,” according to the Lord himself (Acts 1:8). Here the literary device of a journey is a metaphor for the universal extension of the faith. There is but one Savior for humanity, and one people of God to proclaim the same. 47

Pope Paul’s interpretation of the objectives of Vatican II as making the Church “ever better fitted for proclaiming the Gospel to the people of the 20th century,” bespeaks the Council’s resolve to continue the work begun by the Lord himself, and globalized at Pentecost. The Great Commission, like Pentecost, is at once an “already” and a “not yet” for the Church. As a result, the Great Commission, vis-à-vis Matt 28:16–20 and Mark 16:14–18, is cited almost two-dozen times in the conciliar documents, 48 and Matt 28:19–20 is the first quote in Pope Benedict’s Ubicumque et semper. Let us now turn our attention to Vatican II’s call to mission.

Vatican II’s Call to Mission

It is significant that the two dogmatic constitutions of Vatican II—Lumen gentium and Dei Verbum—open with emphasis on the Church’s evangelical nature. Lumen gentium begins thus: “Christ is the Light of nations. Because this is so, this Sacred Synod gathered together in the Holy Spirit eagerly desires, by proclaiming the Gospel to every creature, to bring the light of Christ to all men, a light brightly visible on the countenance of the Church.” 49 Dei Verbum begins in similar fashion: “This present council wishes to set forth authentic doctrine on divine revelation and how it is handed on, so that by hearing the message of salvation, the whole world may believe, by believing it may hope, and by hoping it may love.” 50 With these two sentences, the Council underscores the Church’s missionary nature: to advance the Gospel to “every creature” and to the “whole world.” For the most part, the evangelization projected by the Council was evangelization in the sense in which we usually use the term, that is, spreading the Gospel to those who have not yet heard it. Thus, Ad gentes dealt almost exclusively with “foreign” missions. Pope Paul VI, in reorganizing the Roman Curia immediately after the Council, renamed the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. 51

In its very first sentence, Ad gentes reiterates Lumen gentium’s insight that the Church is “the universal sacrament of salvation,” citing Mark 16:15, and speaking of the Church’s missionary activity as borne out of “obedience to the command of her founder.” 52 Ad gentes declares, “The Church on earth is by its very nature missionary since, according to the plan of the Father, it has its origin in the mission of the Son and the Holy Spirit,” 53 as we noted above. Again, the Church’s understanding of this activity was, during the conciliar years and in its documents, aimed at the missions. But that a new understanding was budding, especially with Pope Paul who would come to refer to the missions and children’s catechesis as a “first proclamation {of the Gospel}” in Evangelii nuntiandi. 54 The Council assumes the necessity and urgency of this first proclamation of the Gospel.

Given that assumption, the Council concerned itself with seeking the most effective ways of evangelizing and reminding all the faithful—clergy, religious, and laity—of their responsibility to proclaim the Gospel, because “the obligation of spreading the faith is imposed on every disciple of Christ.” 55 The Council, however, developed the Church’s doctrine in emphasizing the laity’s responsibility. Heretofore, the responsibility for missionary activity was seen to devolve to clergy and religious. Apostolicam actuositatem, Vatican II’s Decree on the Apostolate of Lay People, notes the Church’s “diversity of ministry but a oneness of mission” and the laity’s proper “share in the mission of the whole people of God in the Church and in the world.” 56 Indeed, the Church should form the “laity to engage in conversation with others, believers, or non-believers, in order to manifest Christ’s message to all men.” 57 Why? For the simple reason, according to Ad gentes, that “the whole Church is missionary, and the work of evangelization is a basic duty of the People of God.” 58

How the Church should go about its evangelical mission to all men is carefully considered by Ad gentes. Preaching is given pride of place, followed closely by example or witness. 59 Ad gentes goes on to note the importance of missionary efforts to save souls through baptism and incorporation into Christ, the good the Gospel brings to all people and societies, and God’s plan for all persons. 60 Nonetheless, the lion’s share of Ad gentes deals with foreign missionary activity per se. 61 For our purposes here, we are well served by turning to Gaudium et Spes, Vatican II’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, for the Council’s rationale about spreading the Gospel. There, the Council fathers say that an “accommodated preaching of the revealed word ought to remain the law of all evangelization.” 62 There, building on Lumen gentium, they mean to express the need for the Gospel to be preached intelligibly to all peoples, cultures, and times. 63 This “law” is truly taken to heart by the Council’s popes, and is foundational to their call for a New Evangelization.

The New Evangelization

Ad gentes speaks of “stages” in missionary activity, and of changes among the faithful, where “an entirely new set of circumstances may arise. Then, the Church must deliberate whether these conditions might again call for her missionary activity.” 64 The New Evangelization is the missionary activity germane to such circumstances in the 21st century.

Pope Paul VI, in Evangelii nuntiandi, knew of the “first proclamation” of the Gospel, to those “who have never heard the Good News of Jesus, or to children.” He also saw “the frequent situations of de-christianization” in his own day necessitating a proclamation of the Gospel to others, namely, “for innumerable people who have been baptized but who live quite outside Christian life, for simple people who have a certain faith but an imperfect knowledge of the foundations of that faith, for intellectuals who feel the need to know Jesus Christ in a light different from the instruction they received as children, and for many others.” 65 Paul goes on to mention the Church’s responsibilities “to deepen, consolidate, nourish and make ever more mature the faith of those who are already called the faithful or believers, in order that they may be so still more.” 66 This he deems necessary because the faith “is exposed to secularism, even to militant atheism,” “to trials and threats,” and the faith is “besieged and actively opposed”; moreover, Paul cites an “increase of unbelief in the modern world.” 67 To that, Paul adds his concern for those who have fallen out of the practice of the faith. They are apathetic to their faith and unlikely to live it, and many “seek to explain and justify their position in the name of an interior religion, of personal independence or authenticity.” 68

All of the above, no doubt manifest to the Third General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops back in 1974, which led Paul to call for “a new period of evangelization.” Nonetheless, such a new period has been slow in starting. John Paul II coined the term “New Evangelization” 30 years ago. Despite his strenuous efforts on behalf of a New Evangelization during his lengthy pontificate, the tide has yet to turn. Paul’s “frequent situations of de-christianization” in 1975 have become de rigueur in 2012. For that reason, Benedict reminds us that “the mission of evangelization, a continuation of the work desired by the Lord Jesus, is necessary for the Church: “it cannot be overlooked; it is an expression of her very nature.” 69 Furthermore, Benedict lays strong emphasis on the need for effective witness to the Gospel by the lives of contemporary Christians. There is an “intrinsic relationship between the communication of God’s word and Christian witness. The very credibility of our proclamation depends on this.” 70 In this, he echoes and quotes Pope Paul: “The Good News proclaimed by the witness of life sooner or later has to be proclaimed by the word of life. There is no true evangelization unless the name, the teaching, the life, the promises, the Kingdom and the mystery of Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God, are proclaimed.” 71

Benedict—by establishing the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, and calling the next Synod of Bishops to consider the theme of “The New Evangelization for the Transmission of the Christian Faith”; and in the upcoming Year of Faith—surely intended to jumpstart Paul’s new period of evangelization. His efforts, it is hoped, along with the promptings of the Spirit in so many other works of the Church, 72 will make the Church of the 21st century ever better fitted for proclaiming the Gospel to the people of the 21st century.

As we have seen, this New Evangelization is well-founded in Scripture and Vatican II. It is built on rock. 73 That being the case, we find ourselves in a privileged, if not difficult, position. We are privileged to have received the gift of faith. We are privileged that God’s grace, and our cooperation with it, have left our souls lush with baptismal waters, precluding the “interior deserts,” so common in our age, of which Benedict speaks. 74 We share in the Spirit-filled life of Pentecost, seeing the fulfillment of the words of the prophet Joel as St. Peter did. And like our forebears, Peter and Paul—the apostles, disciples, and countless saints who have gone before us—the love of Christ urges us on (2 Cor 5:14) to preach the Gospel. Proclaiming the Gospel is our responsibility.

Today, the world is indifferent, if not hostile, to the Gospel, but as Pope Paul reminds us, “the Gospel message is not reserved to a small group of the initiated, the privileged or the elect, but is destined for everyone.” 75 Knowing with St. Paul that God “desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:4), we must follow, with the Spirit’s aid, Jesus, who looked with compassion on the lost crowds of his own day, because they were like sheep without a shepherd, and {taught} them many things” (Mark 6:34). 76 The New Evangelization is a “moment” for us to continue to do the Lord’s work. The New Evangelization is not merely an extension of the mission of Vatican II. It is much more than that, for according to the Council, what we refer to as the New Evangelization is central to the mission of the Church, to the holiness, to the very identity of the People of God as he has called us throughout the history of salvation. “The Holy Spirit, the protagonist of all evangelization, will never fail to guide Christ’s Church in this activity.” 77

Let us conclude with the words of St. Paul and the prophet Isaiah. As Paul reflects on the need to preach the Gospel, he asks: “But how are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!’” (Rom 10:14–15 and Isa 52:7).

- Paul VI, Evangelii nuntiandi, Apostolic Exhortation on Evangelization in the Modern World (December 8, 1975), no. 56. ↩

- John Paul II, Redemptoris missio, Encyclical Letter on the Permanent Validity of the Church’s Missionary Mandate (December 7, 1990), no. 33. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 3 and 33. See also John Paul II’s “Address to CELAM” (Port-au-Prince, Haiti; March 9, 1983) in L’Osservatore Romano (English edition) 16.780 (April 18, 1983). The Latin American Episcopal Conference or Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano is often referred to as CELAM. ↩

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, “Homily at the Mass for the Election of the Roman Pontiff” (April 18, 2005). ↩

- Benedict XVI, “Homily of First Vespers on the Solemnity of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul” (June 28, 2010). ↩

- Benedict XVI, Ubicumque et semper, Apostolic Letter Motu Proprio Data Establishing the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization (September 21, 2010), preamble. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini (September 30, 2010), no. 96. Benedict issued it following the Thirteenth Synod of Bishops (October 7 to October 28, 2008) convened to discuss the Word of God in the life and mission of the Church. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Paul VI, Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 2. Cf. idem, “Address for the Closing of the Third General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops” (October 26, 1974) in Acta Apostolicae Sedis 66 (1974): 634–635, 637. ↩

- The Synod met from September 27 to October 26, 1974. ↩

- Paul VI, Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 2. ↩

- Ibid., no. 15. ↩

- John Paul II, “Address to CELAM, ” no. 9. ↩

- John Paul II, Novo millennio ineunte, Apostolic Letter at the Close of the Great Jubilee Year 2000 (January 6, 2001), no. 40. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Porta fidei, Apostolic Letter Motu Proprio Data for the Indiction of the Year of Faith (October 11, 2011), no. 10. See idem, Ubicumque et semper, which establishes the new Pontifical Council for the New Evangelization. The Year of Faith is also to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the promulgation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. See also Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Note with Pastoral Recommendations for the Year of Faith (January 6, 2012). ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 2; see also Lumen gentium, no. 1. ↩

- Pope John XXIII officially convoked the Second Vatican Council with the papal bull Humanae salutis. Humanae salutis ends with the last part of a prayer that had been written to the Holy Spirit for the happy conclusion and for the enriched indulgences of an ecumenical council (see Acta Apostolicae Sedis 51 {1959}, 832): “Renova aetate hac nostra per novam veluti Pentecostem mirabilia tua, atque Ecclesiae Sanctae concede, ut cum Maria, Matre Iesu, unanimiter et instanter in oratione perseverans, itemque a Beato Petro ducta, divini Salvatoris regnum amplificet, regnum veritatis et iustitiae, regnum amoris et pacis. Amen.” It is an allusion to Acts 1:12–14. ↩

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Doctrinal Note on Some Aspects of Evangelization (December 3, 2007), no. 2 (italics original). ↩

- See Benedict XVI, “Homily at First Vespers on the Solemnity of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.” ↩

- See Benedict XVI, Ubicumque et semper. ↩

- Benedict XVI, “Homily at First Vespers on the Solemnity of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.” ↩

- See Synod of Bishops, Lineamenta {text written in preparation} for the New Evangelization for the Transmission of the Christian Faith (February 2, 2011); and idem, Instrumentum laboris {working document} for XIII Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops for the New Evangelization for the Transmission of the Christian Faith (June 19, 2012). ↩

- See Benedict XVI, Porta fidei (October 11, 2011); and Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Note with Pastoral Recommendations for the Year of Faith (January 6, 2012). Cf. Benedict XVI, “Homily at First Vespers on the Solemnity of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.” ↩

- John Paul II, Redemptoris missio, no. 90. ↩

- Other key passages in the Old Testament are Deut 7:6–8; 9:4–6; 2 Sam 7:8–16; Isa 41:8–16; 42:1–9; 43:1–3; and 44:1–5. ↩

- In the New Testament, it is used only two other times: Acts 9:15 and 2 Peter 1:10. In Acts 9, after Paul’s encounter with the Risen Lord on the Damascus road, Ananias, representing the many in the early Church who feared Saul because of his earlier life of persecution, protests the Lord’s (s)election (vv. 13–14); but the Lord says to him, “Go, for he is an instrument whom I have chosen to bring my name before Gentiles and kings and before the people of Israel” (v. 15). In 2 Pet 1:10, Peter sees election as something to be confirmed, that is, calling for a proper response. ↩

- For example, the noun eklektos is used in Matt 22:14; 24:22, 24, 31; Mark 13:20, 22, 27; Luke 18:7; 23:35; Rom 8:33; 16:13; Col 3:12; 1 Tim 5:21; 2 Tim 2:10; Titus 1:1; 1 Pet 1:1; 2:4, 6, 9; 2 John 1:1, 13; Rev 17:14. The verb thelō is used in Matt 8:2–3; 20:14–15; Mark 1:40–41; Luke 5:12–13; John 8:44. The verb form of eklogē, eklegomai, is used in Mark 13:20; Luke 6:13; 9:35; 10:42; 14:7; John 6:70; 13:18; 15:16, 19; Acts 1:2, 24; 6:5; 13:17; 15:7, 22, 25; 1 Cor 1:27–28; Eph 1:4; Jas 2:5. ↩

- For example, the threats of Assyria and Babylon in 2 Kgs 21:14; Amos 5:15; Isa 1:8–9; 6:13; and 7:3–4. The remnant held a promise of hope, for example, in Sir 44:17 and 47:22. ↩

- Solemn Intercessions for the Celebration of the Passion of the Lord in the Roman Missal (third official English translation, 2010). ↩

- Lumen gentium, no. 39; see also no. 4. ↩

- Ibid., no. 9. ↩

- See Benedict XVI, “General Audience” (March 2, 2011). ↩

- Pius XI, Casti connubii, Encyclical Letter on Christian Marriage (December 31, 1930), no. 23. ↩

- Lumen gentium, no. 9. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 9 and 48; cf. Ad gentes, no. 1. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 9 and 48; cf. Ad gentes, no. 1. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 39–44. ↩

- Ibid., no. 41. ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 2. See also Lumen gentium, no. 1. ↩

- John Paul II, Redemptoris missio, no. 90. ↩

- Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini, no. 94. Benedict is emphatic that no Christian may shirk his or her duty in this regard by specifically mentioning the corporate and individual responsibility of bishops, priests, deacons, religious, and laity. ↩

- Matt 28:16–20 and Mark 16:14–18; cf. Matt 10:5–42; Luke 10:1–20; 24:44–49; Acts 1:4–8; and John 20:19–23. ↩

- Mark 6:1–6; cf. Matt 13:53–58; and Luke 4:16–30. ↩

- Cf. Matt 10:1–15 and Luke 10:1–16. ↩

- Rom 14:14; Galatians 2; 1 Corinthians 8 and 9; Titus 1:5; and Acts 10. ↩

- Mark explains Jewish customs (e.g., 7:3; 14:12; 15:42) and translates Aramaic expressions (e.g., 3:17; 5:41; 7:11, 34; 9:43; 10:46; 14:36; 15:22, 34). Mark transliterates Latin military terms (e.g., legion in 5:9, praetorium in 15:16, centurion in 15:39). There is also some evidence that Mark was writing to Roman Christians. Peter and Mark were together in Rome (2 Tim 4:11; 1 Peter 5:13). ↩

- For more on this, see Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Dominus Iesus: On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church(August 6, 2000). ↩

- For Matthew, see Lumen gentium, nos. 17, 19, and 24; Dei Verbum, no. 7; Ad gentes 5; Dignitatis humanae 13 and 14. For Mark, see Lumen gentium, nos. 1, 16, 19, and 24; Dei Verbum, no. 7; Unitatis redintegratio, no. 2; Orientalium ecclesiarum, no. 3; Ad gentes, nos. 1, 5, and 38. ↩

- Lumen gentium, no. 1, alluding to Mark 16:15. ↩

- Dei Verbum, no. 1, alluding to St. Augustine, “De Catechizandis Rudibus,” C. IV 8, Patrologia Latina 40, 316. ↩

- Paul VI, Regimini Ecclesiae Universae (August 15, 1967). Here Paul was responding directly to Ad gentes, no. 29. ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 1, citing Luman gentium, no. 48. ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 2, citing Luman gentium, no. 1. ↩

- Evangelii nuntiandi, nos. 45, 51–53, and 55 (italics added). ↩

- Lumen gentium, no. 17; see also no. 33. See also Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini, no. 94. ↩

- Apostolicam actuositatem, no. 2. ↩

- Ibid., no. 31a; cf. no. 29. ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 35. ↩

- Ibid., no. 6. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 7, 8, and 9. ↩

- Ibid., nos. 10 through 42. ↩

- Gaudium et Spes, no. 44. ↩

- See Lumen gentium, no. 13. ↩

- Ad gentes, no. 6. ↩

- Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 52. ↩

- Ibid., no. 55. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., no 56. ↩

- Ubicumque et semper, preamble; cf. Ad gentes, no. 2. ↩

- Verbum Domini, no. 97 (italics original). ↩

- Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 22; it is quoted in Verbum Domini, no. 98. ↩

- There is a great deal of discussion about the New Evangelization in terms of the so-called “new media” and the huge advantages in technology. Pope Paul VI counsels wisely, “Techniques of evangelization are good, but even the most advanced ones could not replace the gentle action of the Spirit” (Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 75). See also Verbum Domini, no. 97. ↩

- See, for example, Matt 7:24; Luke 6:48; and 1 Cor 10:4. ↩

- Ubicumque et semper, preamble. ↩

- Evangelii nuntiandi, no. 57. ↩

- Cf. Matt 9:36; 15:32; and 1 Pet 2:25. ↩

- Verbum Domini, no. 97. ↩

The essay never mentions gigantic problems that militate against reclaiming drift away Catholics.

One is forty years of sexual scandal and abuse of youngsters by priests… that should have called for a Council that never happened. That Council should have asked how the crisis produced no hero amongst the Popes or Cardinals…heroes that would have placed action ahead of preserving the canonical slowness of our legal system. That Council never happened and millions of human beings know that. St. Paul did not have that baggage as he evangelized. Benedict noticed moral relativism in society without noticing systemic hierarchy failure inside. Is this the season to evangelize or is it the season to call a Council to seek the cause of hero failure at the top of the Church while in some cases, children were being violated often in the name of obedience to father x.

Being a victim of a priest’s sexual advances as a teenager, I also experienced, and do experience (at the age of 67), the goodness of many more priests, bishops, popes, and laity than the one priest. The Church is more than the abuse, real as it is and was. Thank God. Let’s also proclaim the goodness of Jesus and His bride, the Church.

Rachel,

Unfortunately the stats on a higher level of abuse than advances were surprising to me. This quote is from the usccb site summarising the John Jay report: ” 27.3% of the allegations involved the cleric performing oral sex on the victim. 25.1% of the allegations involved penile penetration or attempted penetration.”

That is another level of abuse entirely…but secondly the world knows that we did not examine our hero abscence at the top where the power was present to undertake the drastic rather than the bureaucratic…but against pressures. The literate world knows this and you won’t as easily evangelize them as you will the less well read. It depends whom one is evangelizing.

ps….here is my Diocese and Bishop flagrantly endangering youth right now as reported by Deacon Kandra at Patheos Catholic today…

http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2013/04/with_approval_of_archbishop_pr.html

And here is the other side of the Newark story, showing that Archbishop Myers did not (flagrantly or otherwise) endanger youth . . .

http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/newark-archdiocese-says-media-mischaracterizing-accused-priest/

Here’s the diocesan spokesman, Goodness…” “What we do know is that Fr. Fugee did participate in a couple different retreats over a period of time…but he had been asked to come in at the last minute to hear confessions and say Mass with another priest,” Goodness said.

That means the Bishop has to remove him from ministry according to the prosecutor’s agreement whether the prosecutor folows up or not.

Why? Because confessions are never supervised by their nature..and the confessional setting is germane to some incidents of sexual abuse so much so that Pope John xxiii had sent a controversial letter years ago specifically about seduction in the confessional. It’s on the internet.

Here’s both the good and bad from witnesses on Bishop Myers prior to Newark..

http://www.bishop-accountability.org/news3/2002_06_02_McRoberts_BishopOn_John_Anderson_1.htm

The Bergen County prosecutor disagreed with the diocesan defense mentioned by Bain. Go here:

http://www.northjersey.com/news/crime_courts/Bergen_County_prosecutor_probing_if_priest_violated_agreement_in_molestation_case.html?page=all&scpromo=1

Fr. Fugee has resigned ministry. Prosecutor still calling in witnesses regardless… as to compliance with the prosecutors/ diocesan pact. The pact was a substitute for the priest being retried after the first guilty verdict was overturned on appeal.

http://www.northjersey.com/news/Priest_at_heart_of_Newark_Archdiocese_sex_abuse_scandal_resigns.html?scpromo=1

Relevance to Evangelisation of all this? Laity going door to door to woo back drift away Catholics in the Newark Archdiocese should be honest with their listeners about Bishop Myers history ( his successor Bishop in Peoria immediately processed against 7 priests on sexual matters wherein Myers hadn’t etc…..see my first link). Does the evangelisation go like this: “Come back to Church in Newark Archdiocese but are your children safe… we really can’t vouch for that….the Bishop of Trenton says Fr. Fugee did not have permission to be in his diocese and Trenton was not given a headsup from Newark…now two law makers, Michael Sean Winters and a major newspaper want Archbishop Myers out of office.”. Will evangelizers note such things about Myers? Or will our evangelization resemble

dishonest sales techniques from the used car industry. The Church is perfectly Holy in Her sacraments, in Her dogmas of a certain nature, and in her approved liturgy. She is only sporadically Holy in lay, clergy, religious, and papal behaviour. Where the latter is even more compromised in a region than normal, then few will evangelize with perfect candor. “Was this car ever in an accident? The bumper is tilted.”

My comment on 3 May was in response to this claim (which I took to be a reference to Newark and Archbishop Myers) made in a comment on 29 April:- “my Diocese and Bishop [are] flagrantly endangering youth right now”. What was the basis for this claim?

The link included in the 29 April comment baldly asserts that the contact allegedly in breach of the agreement with the prosecutor occurred “. . . with the approval of New Jersey’s highest-ranking Catholic official, Newark Archbishop John J. Myers” – but it is precisely that assertion which is contested in the link I gave.

It is now tolerably clear that the only contact allegedly in breach of the agreement with the prosecutor occurred in the dioceses of Trenton and Paterson. I have seen no suggestion that any inappropriate contact occurred in the Archdiocese of Newark, nor have I seen any indication that Archbishop Myers or any senior person at the Newark Chancery had prior knowledge of or gave prior approval to the activities Fr. Fugee undertook in the diocese of Trenton or Paterson.

So…you would feel safe leaving your grandchildren under Bishop Myer’s fathership as demonstrated in both Peoria and Newark? I think not. I think you’d advise your offspring to not relocate under his fathership….whatever you debate on the internet. In Peoria his successor removed 7 priests immediately in his first 8 weeks of office…whom Myers had not removed in years. Under the tone set by that Bishop Jenky, Fr. Fugee under such fathership would not have dared venturing into other dioceses to begin with…especially avoiding giving them suitability papers. Knowing Bishop Myer’s history with him and in Peoria, Fr. Fugee felt free to invade two other diocese and hear youth confessions. Had a youth confessed gay acts, Fr. Fugee might have suggested a private dialogue somewhere which an alleged supervisor could not hear due to the seal of confession requirements.

Myer’s history in Newark according to bishopaccountability dot org:

http://www.bishop-accountability.org/news2010/11_12/2010_12_05_Diamant_NewarkArchbishop.htm

I am not interested in “debating”, only in the truth, and in what can count as fair comment.

It is claimed that it is to the discredit of Archbishop Myers, when bishop of Peoria, that his successor “removed 7 priests immediately in his first 8 weeks of office…whom Myers had not removed in years”.

Well, what did Myers’ successor (Bishop Jenky) himself say about that in 2002 when addressing a gathering of his diocesan priests :-

“Bishop Jenky also disputed a story carried on the front page of that day’s Chicago Tribune, and widely publicized in other media, implying that Archbishop Myers was dropped from the U.S. bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on Sexual Abuse because of questions about his handling of such cases during his more than 11 years as bishop of Peoria. ‘I got a little angry reading that story,’ he said. ‘It is not true.’

“Bishop Jenky reiterated that to the best of his knowledge only one of the eight cases in which he has removed priests from ministry involved allegations that Archbishop Myers did not resolve before he left the diocese last fall. Any notion that Archbishop Myers was negligent in handling such cases is not warranted by the facts, he added.”

see http://www.jknirp.com/spencer.htm

Bain, tell us how a brand new Bishop removed 8 priests in his first two months without the prior Bishop knowing a thing about 7 of them. How do you see plausibility in that scenario? It is only plausible if as soon as he entered Peoria, witnesses who found no hearing with Myers flooded Jenky with testimony or ( implausibly) 7 abusers miraculously confessed to Jenky but wouldn’t to Myers. Normally it takes months to remove 7 priests. Jenky’s defense of Myers ( presuming the paraphrase is accurate…we are not given his words after the little bit angry quote) actually leaves the reader with that question: how is it plausible that seven men unknown to Myers were removed in 8 weeks by Jenky.

As regards your initial outrage at my first link to the star ledger for saying that the Archdiocese gave Fugee approval of his actions, the reason the Star Ledger said that was the words in that article by Archdiocesan spokesman, Goodness, who portrayed Fugee and the Diocese as working as a unit,

in the article that offended you: ” We believe that the Archdiocese and Fr. Fugee have adhered to the stipulations in all of his activities and will continue to do so” Goodness said…” The fact is he has done nothing wrong.”. The paper, the 16th largest in the US, reasonably took that for unity between an authority and an underling.

Days later, Goodness reversed that: ” He engaged in activities that the Archdiocese was not aware of and that were not approved by us..”

But to return to Peoria: show us how a new Bishop could remove 7 priests in his first 8 weeks without the prior Bishop being aware of allegations against them….7 totally unknown priests removed without the prior Bishop having received a complaining letter against them prior to those 8 weeks.

Explain how that can be plausible.

I really have no idea why you want to draw me further and further into these issues. Quite evidently it is Bishop Jenky who has the answer to your questions, not me. Your animus against Archbishop Myers seems to be based on supposition and innuendo.

I have no interest in pursuing this matter with you, and my comments are intended only to show that your opinions are precisely that.

Bain,

Be aware of a greater problem across many issues in Catholicism which Church I believe in.

That problem is a cover up tradition within Catholicism on embarassing issues. Pope Leo XIII warned Catholic scholars against non objectivity in a letter to them. But Federal Judge John C. Noonan Jr. showed in his “The Church that Can and Cannot Change” ( Nortre Dame) that Leo XIII himself in his letter to Brazilian Bishops wherein he praised the Church as prime hero against slavery was leaving out the four Popes at the end of the 15th century who turbo charged slavery by Iberia. (see mid 4th large paragraph of Romanus Pontifex).

Check the discrepancy on the Inquisition’s burnings at the stake of heretics given by two Catholic sources. The article at new advent’s Catholic Encyclopedia says Popes starting in AD 1253 mandated secular authorities to burn heretics or themselves face excommunication ( sect.D of ” The New Tribunal”)…” The civil authorities, therefore, were enjoined by the popes, under pain of excommunication to execute the legal sentences that condemned impenitent heretics to the stake.”

Then check Catholic author, Thomas Madden saying the exact opposite at National Review:

” Despite popular myth, the Inquisition did not burn heretics. It was the secular authorities that held heresy to be a capital offense, not the Church. The simple fact is that the medieval Inquisition saved uncounted thousands of innocent (and even not-so-innocent) people who would otherwise have been roasted by secular lords or mob rule.”. . http://old.nationalreview.com/comment/madden200406181026.asp

You Bain, have a very good intellect that I’ve seen elsewhere more vividly. The Church needs you as a real intellectual to notice that the coverup tendency far preceded the coverups of the sex abuse period. It’s found on every embarassing issue because it was a reaction to Protestant hyperbole against us…but we then answered often with hyperbole of flattering our selves and our history. Secular newspapers saved our children in 2002 while our own diocesan press often simply listed nun anniversaries while sexual crimes were driving many from both the Church and God…( 40 suicides in Victoria, Australia linked by police to clergy sexual abuse).

Catholicism is Holy in its sacraments, sure dogma, and approved liturgy. We went a step further and said our history in the world was Holy…and it’s not. Primitives and fleeing Protestants can be converted without our giving up cover up tradition….but millions are leaving because inchoately they sense something wrong. The Church is the Bride that needs our sweat…not mascara or lipstick.

“ God is opening before the Church the horizons of a humanity more fully prepared for the sowing of the Gospel. I sense that the moment has come to commit all of the church’s energies to new evangelization and to the mission, Ad Gentes. No believer in Christ, no institution of the cChurch can avoid this supreme duty: to proclaim Christ to all people.” (RM 3).